TRACES: Peter Halley

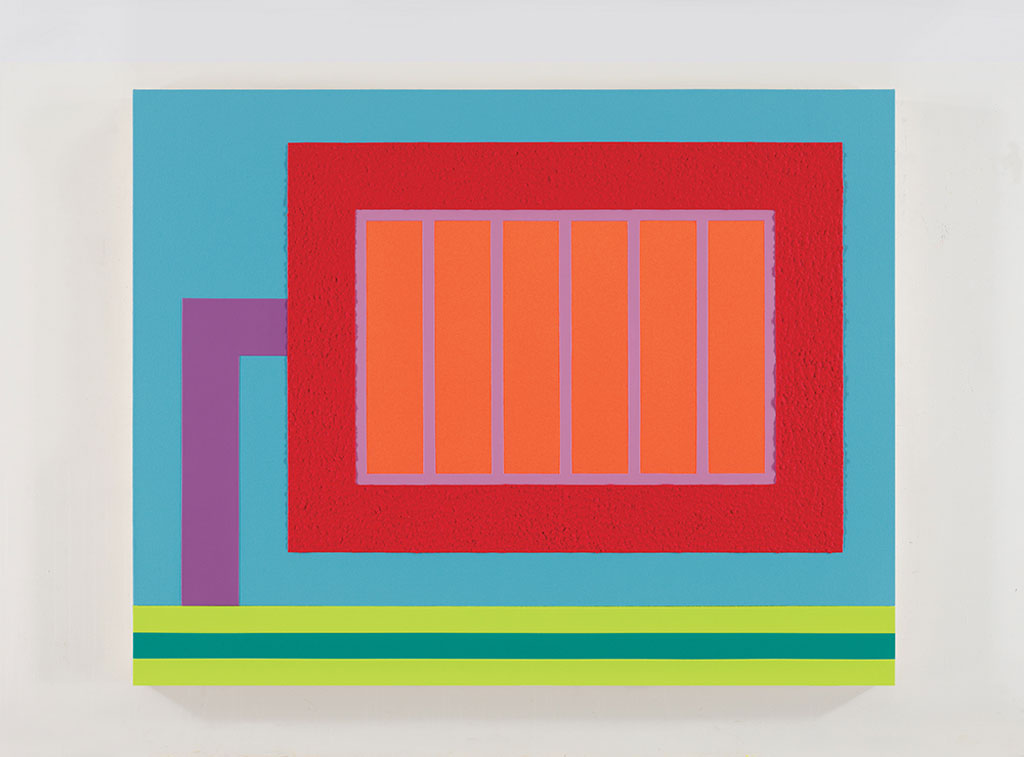

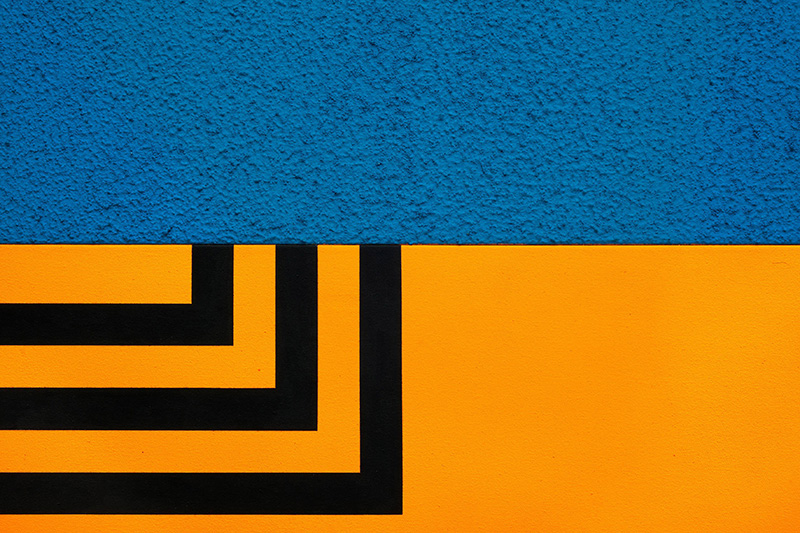

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Peter Halley (24/9/1953- ), one of the most emblematic artists of his generation, recognized in the history of contemporary painting as the legitimate heir of American abstraction. Peter Halley is best known for his brightly colored, geometric paintings made of Roll-a-Tex, a textured paint used for decoration, as well as florescent Day-Glo paints. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Peter Halley (24/9/1953- ), one of the most emblematic artists of his generation, recognized in the history of contemporary painting as the legitimate heir of American abstraction. Peter Halley is best known for his brightly colored, geometric paintings made of Roll-a-Tex, a textured paint used for decoration, as well as florescent Day-Glo paints. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Dimitris Lempesis

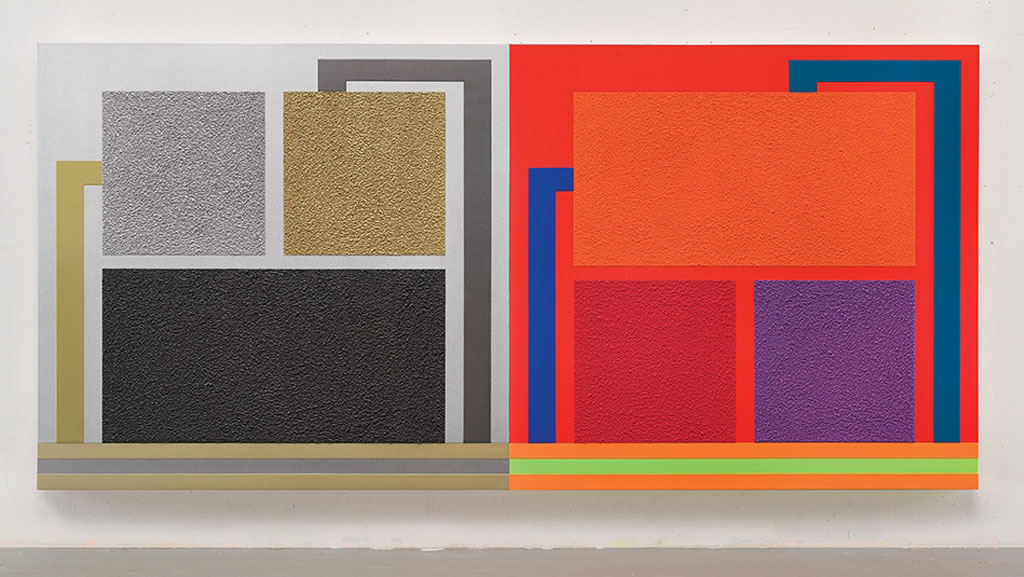

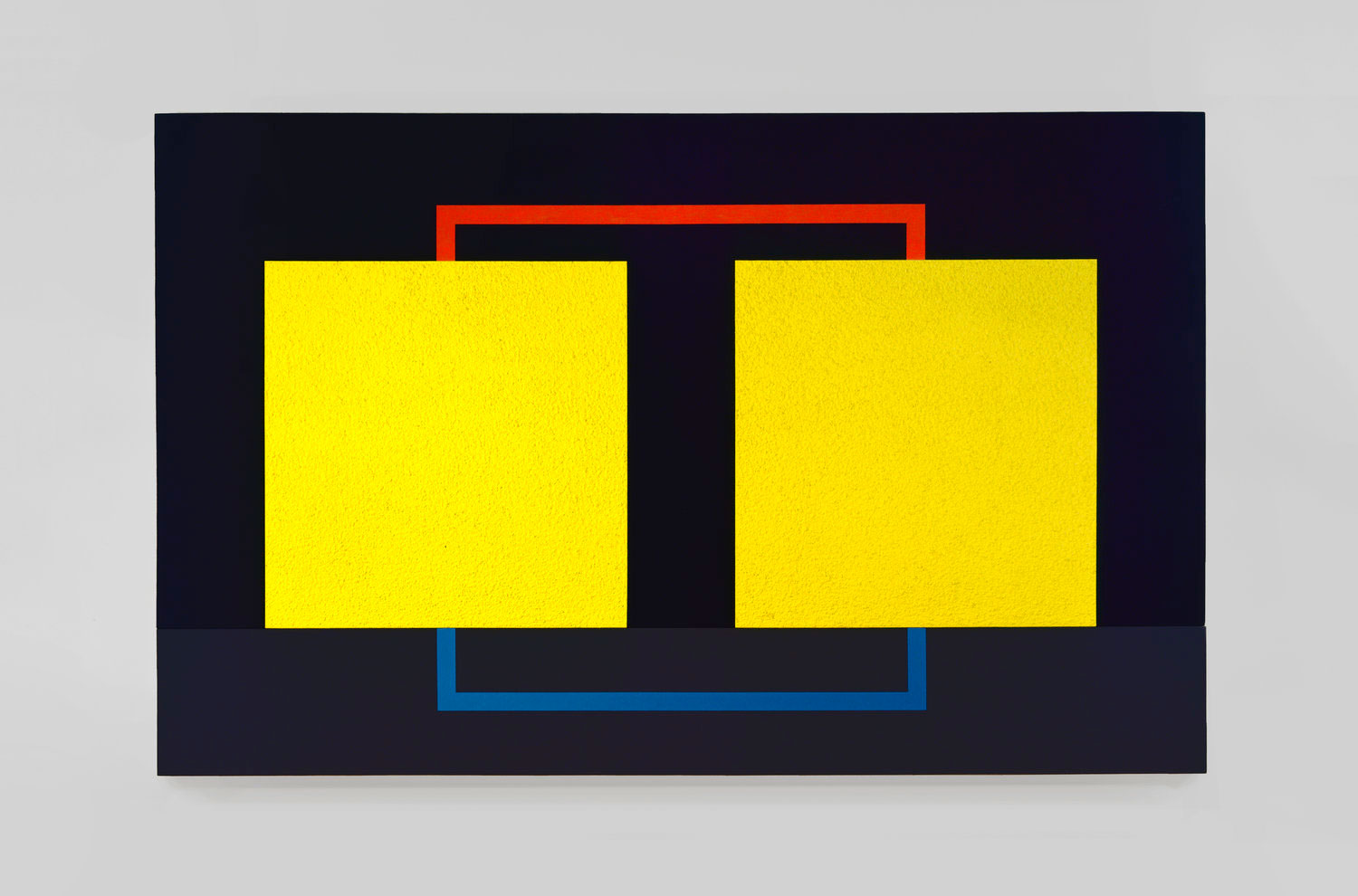

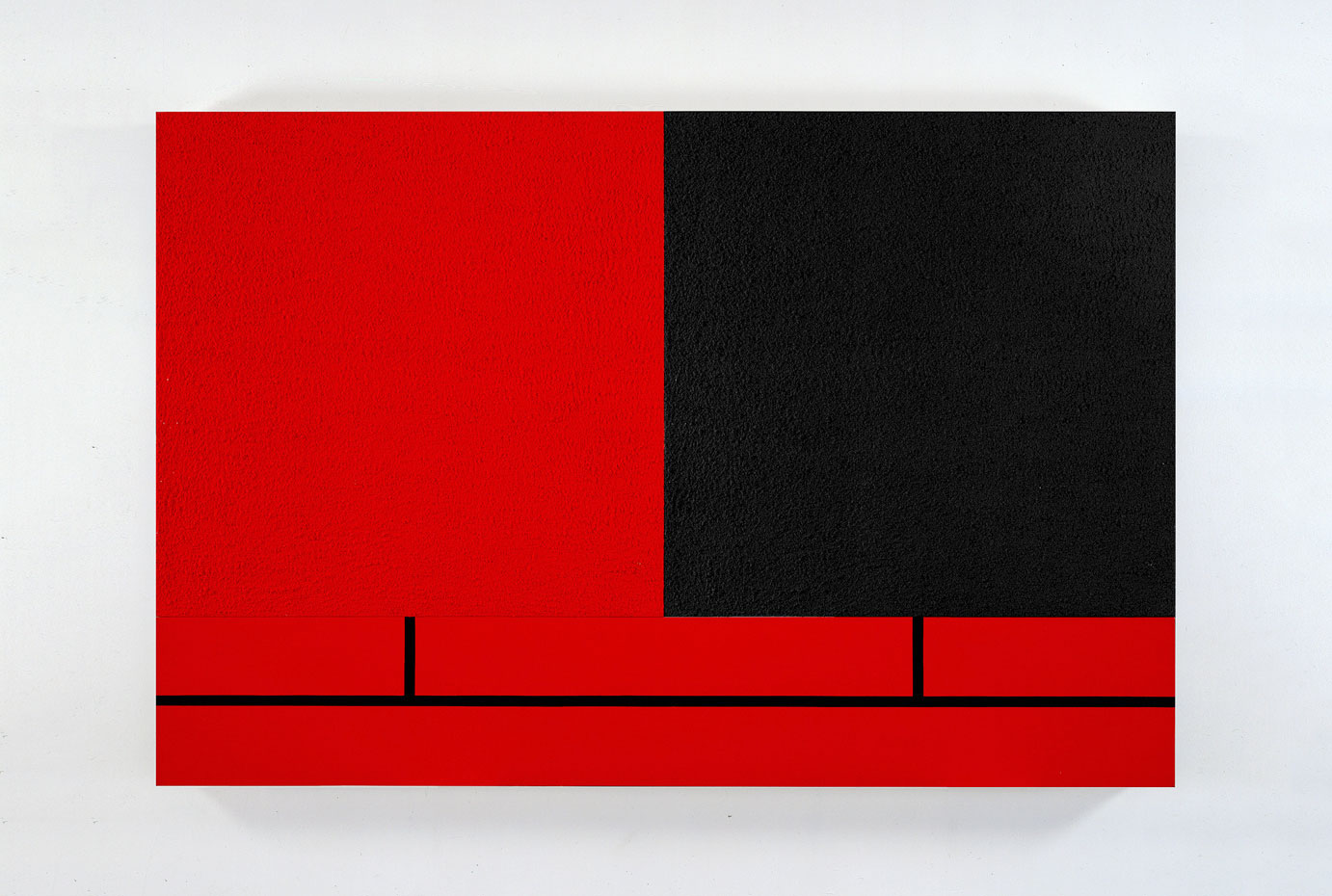

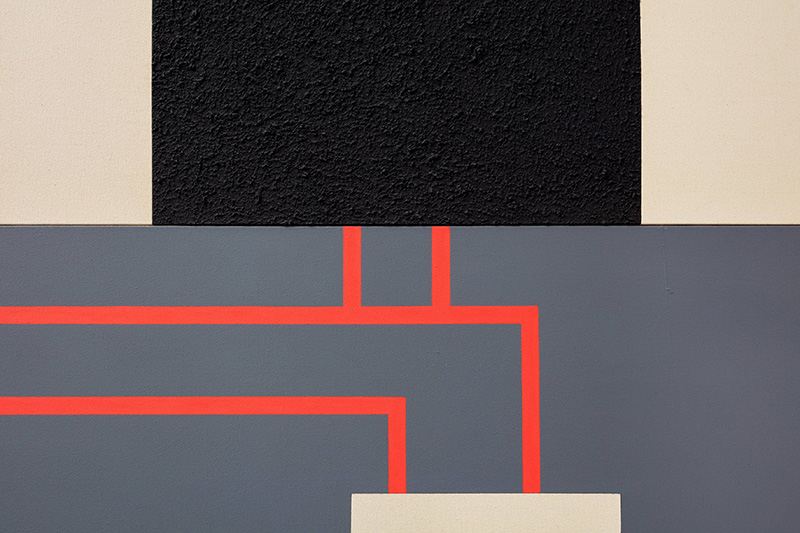

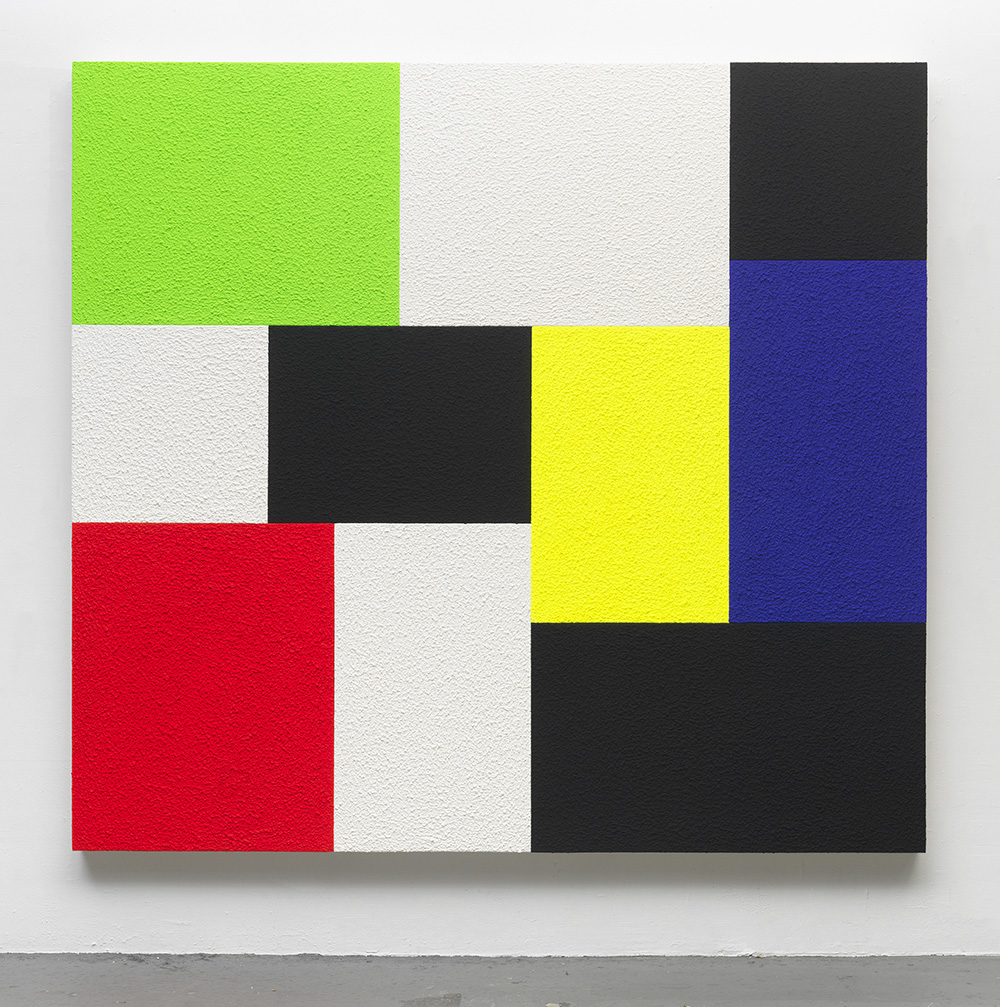

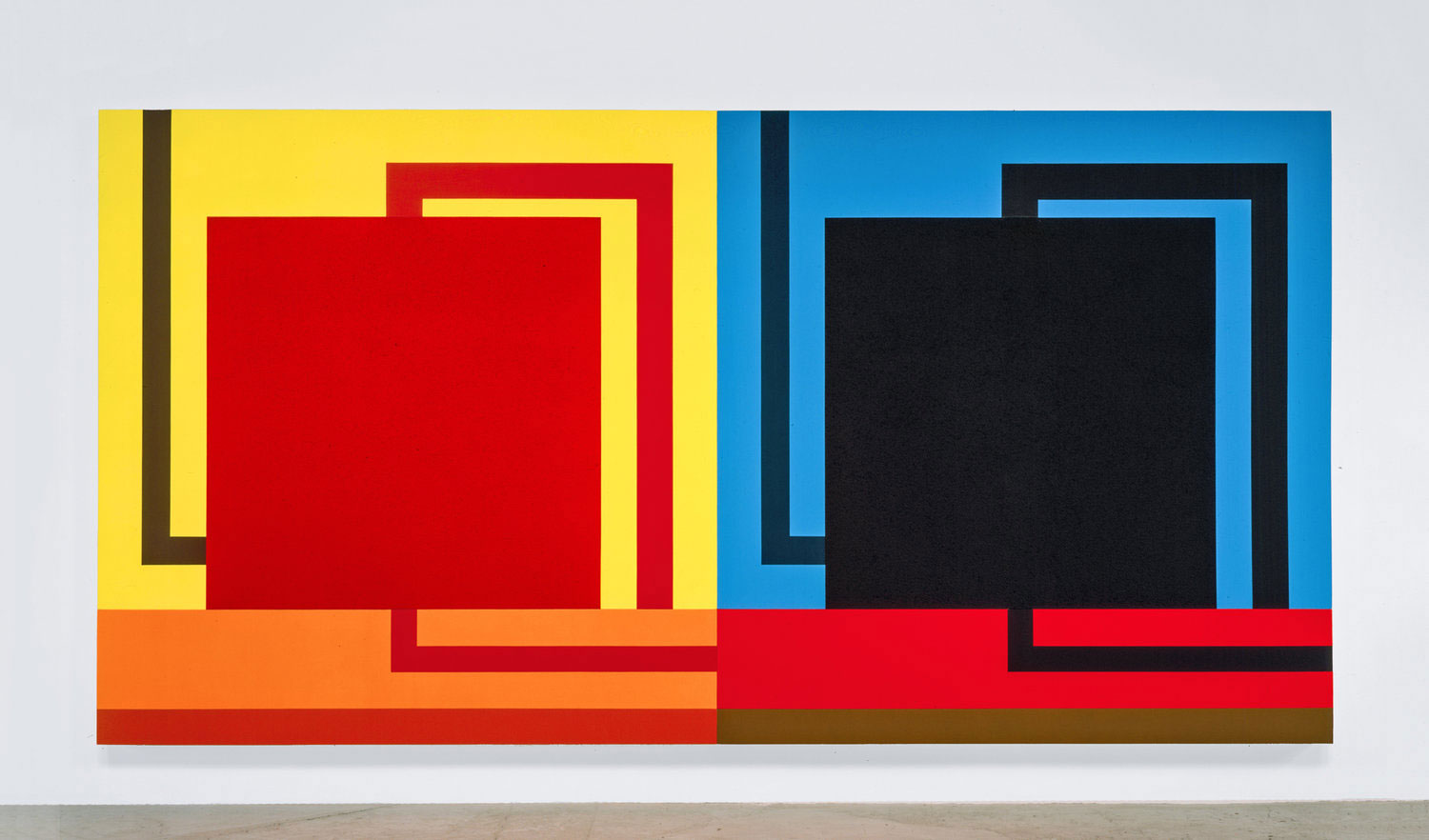

Born in 1953 in New York City, Halley completed his BA in art history at Yale University, New Haven, and, later, completed his MFA at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, from which he graduated in 1971. During that time, Halley read Josef Albers’s “Interaction of Color” (1963), which would influence him throughout his career. Following his graduate studies, he moved back to New York in the early 1980s, and was soon given his first solo exhibition at PS122 Gallery. His early works included references to pop culture as well as broader social issues, but as his practice developed he began incorporating higher degrees of geometric abstraction as well as his signature use of Day-Glo paint. Developing his own visual lexicon, Halley engages in a play of relationships between what he calls “prisons” and “cells”(composed of rectangular shapes and vertical bars) evocative of geometric networks from the urban grid to high-rise apartment buildings to electromagnetic conduits. While his rigid planes of color, unitary shapes, and non-hierarchical compositions nod toward Minimalism, by transforming the Minimalist square into a prison cell, Halley’s works call the supposed neutrality of such art into question. Halley, along with other contemporaneous artists working within the scope of neo-conceptualism such as Sarah Charlesworth, Annette Lemieux and Jeff Koons, sought to simultaneously highlight and critique the roles that physical and technological powers play in an increasingly commodity-driven society. Ultimately, his oeuvre on a whole, including his paintings, sculptures and writings, profoundly impacted the development of American post-modern intellectualism. Along with Bob Nickas, Halley co-founded “Index” magazine in 1996, which featured interviews with figures in the artistic fields, similar to Andy Warhol’s “Interview” magazine; the magazine was considered an important art publication throughout its run until its final issue in 2005. As both author and artist, Halley has drawn upon the writings of the French theoreticians Michel Foucault and Jean Baudrillard to articulate and substantiate his dual critique of culture and art. Foucault’s analysis of the geometric organization of industrial society, particularly institutional modes of confinement, inspired Halley to transform a Minimalist square into a prison cell by adding three vertical bars to the form. In response to Baudrillard’s exploration of postindustrial culture: its reliance on information systems, media representation, and an economy that privileges image over product, Halley shifted to schematized depictions of enclosed spaces, linked to the world through a network of electronic, telephonic, and fiber-optic conduits. In addition to his painting and writing, Halley has had a significant teaching career at Columbia University, New York, the University of California, Los Angeles, and Yale University. Many of his works are installed in public spaces, including a forty-foot painting at the Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport and a five-floor permanent installation at the Gallatin School at New York University. His works can be found in the permanent collections of the Art Institute of Chicago, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, the Tate Modern, London, and many other major museums around the world.

Born in 1953 in New York City, Halley completed his BA in art history at Yale University, New Haven, and, later, completed his MFA at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, from which he graduated in 1971. During that time, Halley read Josef Albers’s “Interaction of Color” (1963), which would influence him throughout his career. Following his graduate studies, he moved back to New York in the early 1980s, and was soon given his first solo exhibition at PS122 Gallery. His early works included references to pop culture as well as broader social issues, but as his practice developed he began incorporating higher degrees of geometric abstraction as well as his signature use of Day-Glo paint. Developing his own visual lexicon, Halley engages in a play of relationships between what he calls “prisons” and “cells”(composed of rectangular shapes and vertical bars) evocative of geometric networks from the urban grid to high-rise apartment buildings to electromagnetic conduits. While his rigid planes of color, unitary shapes, and non-hierarchical compositions nod toward Minimalism, by transforming the Minimalist square into a prison cell, Halley’s works call the supposed neutrality of such art into question. Halley, along with other contemporaneous artists working within the scope of neo-conceptualism such as Sarah Charlesworth, Annette Lemieux and Jeff Koons, sought to simultaneously highlight and critique the roles that physical and technological powers play in an increasingly commodity-driven society. Ultimately, his oeuvre on a whole, including his paintings, sculptures and writings, profoundly impacted the development of American post-modern intellectualism. Along with Bob Nickas, Halley co-founded “Index” magazine in 1996, which featured interviews with figures in the artistic fields, similar to Andy Warhol’s “Interview” magazine; the magazine was considered an important art publication throughout its run until its final issue in 2005. As both author and artist, Halley has drawn upon the writings of the French theoreticians Michel Foucault and Jean Baudrillard to articulate and substantiate his dual critique of culture and art. Foucault’s analysis of the geometric organization of industrial society, particularly institutional modes of confinement, inspired Halley to transform a Minimalist square into a prison cell by adding three vertical bars to the form. In response to Baudrillard’s exploration of postindustrial culture: its reliance on information systems, media representation, and an economy that privileges image over product, Halley shifted to schematized depictions of enclosed spaces, linked to the world through a network of electronic, telephonic, and fiber-optic conduits. In addition to his painting and writing, Halley has had a significant teaching career at Columbia University, New York, the University of California, Los Angeles, and Yale University. Many of his works are installed in public spaces, including a forty-foot painting at the Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport and a five-floor permanent installation at the Gallatin School at New York University. His works can be found in the permanent collections of the Art Institute of Chicago, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, the Tate Modern, London, and many other major museums around the world.