ART-PRESENTATION: Vertigo Op Art and a History of Deception 1520-1970,Part II

Of all the Art Movements of the 1950s and 60s, Op Art has received the least amount of attention to date. It has often been discounted as too spectacular and showy and therefore not very profound. But this attitude fails to recognize Op Art’s unique ability to raise our awareness for the ambivalence of reality as it tangibly demonstrates that perception is far from objective but rather quite easy to destabili- ze and deceive. It shows us that how we see things always depends on our point of view, with all the epistemological consequences (Part I).

Of all the Art Movements of the 1950s and 60s, Op Art has received the least amount of attention to date. It has often been discounted as too spectacular and showy and therefore not very profound. But this attitude fails to recognize Op Art’s unique ability to raise our awareness for the ambivalence of reality as it tangibly demonstrates that perception is far from objective but rather quite easy to destabili- ze and deceive. It shows us that how we see things always depends on our point of view, with all the epistemological consequences (Part I).

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Mumok Archive

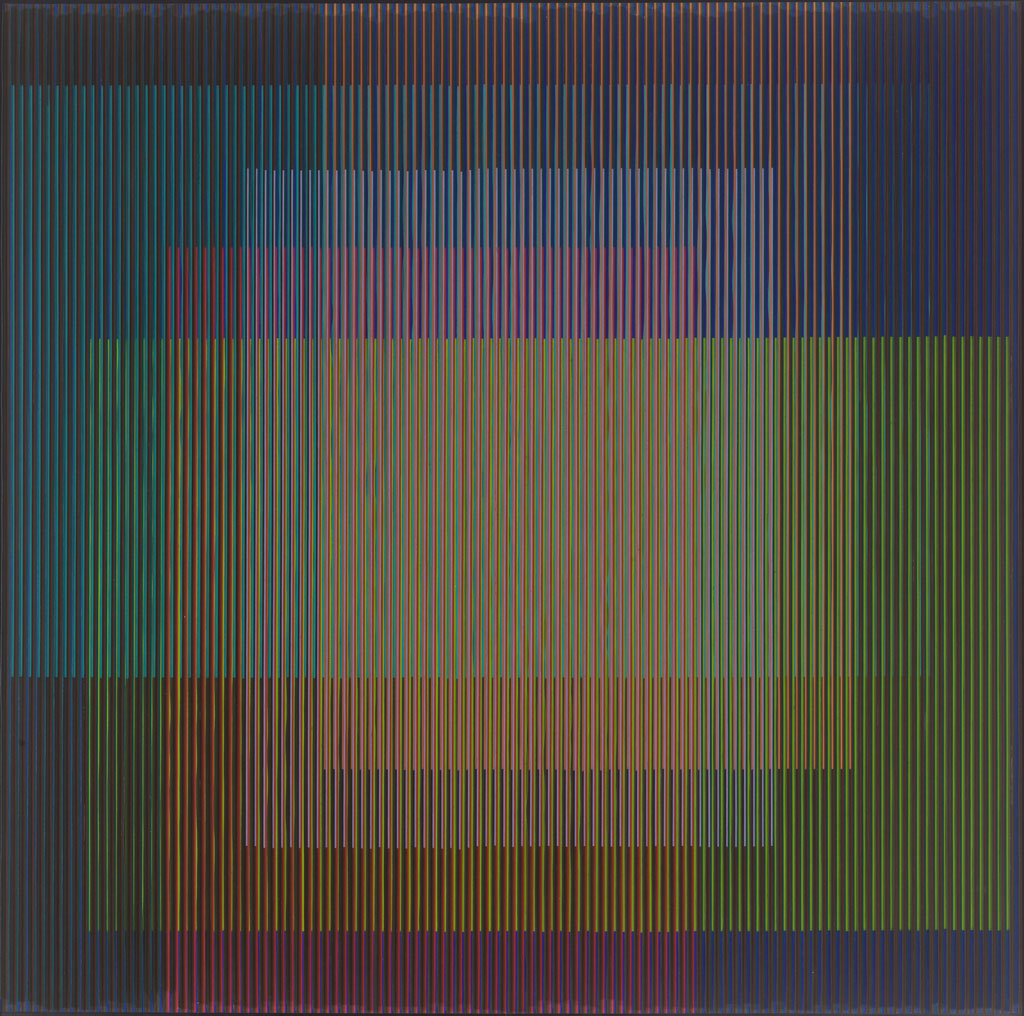

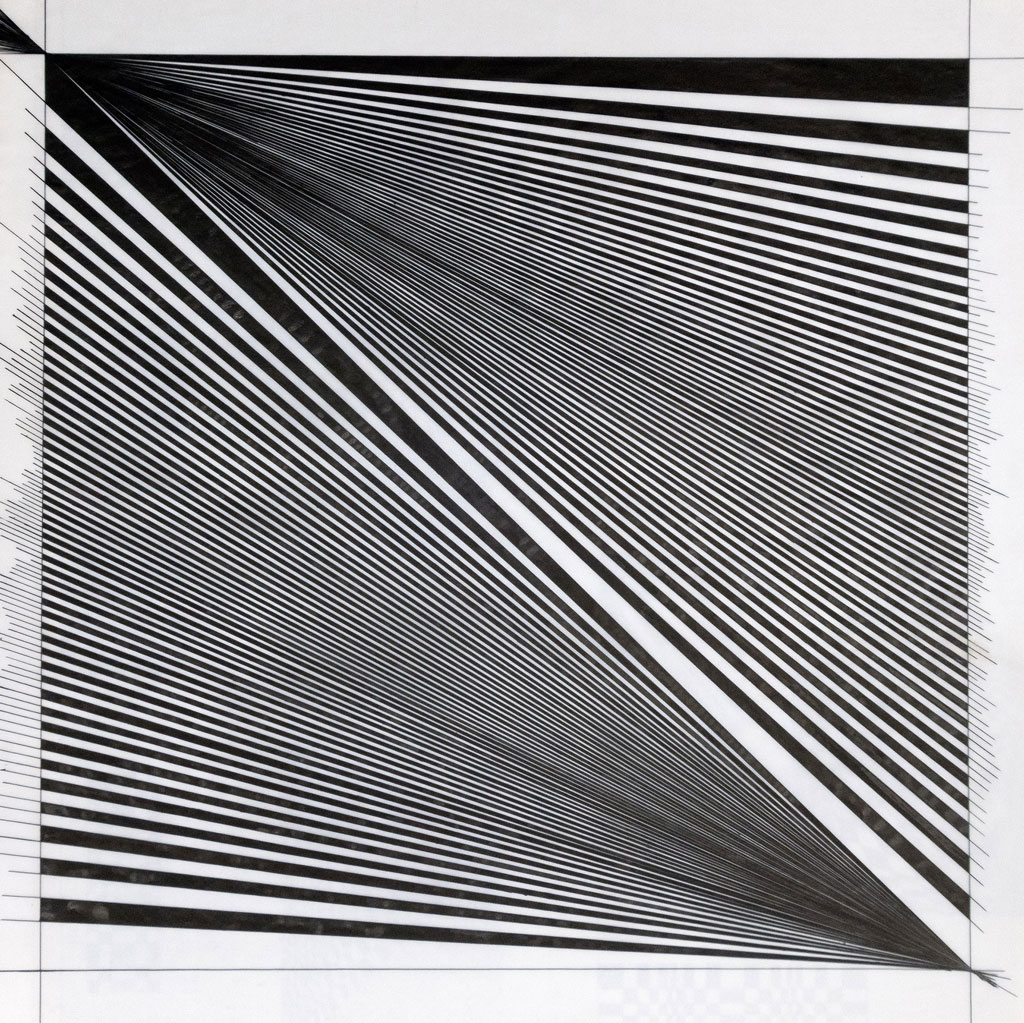

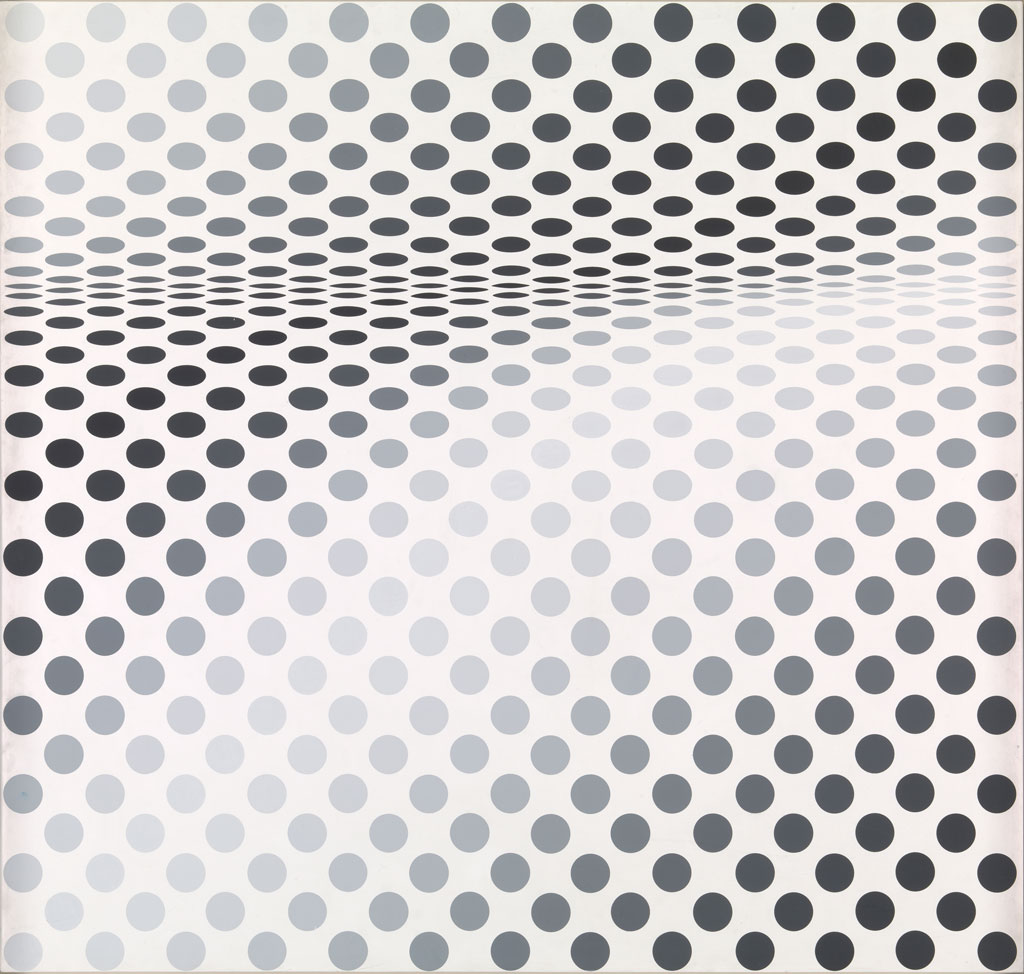

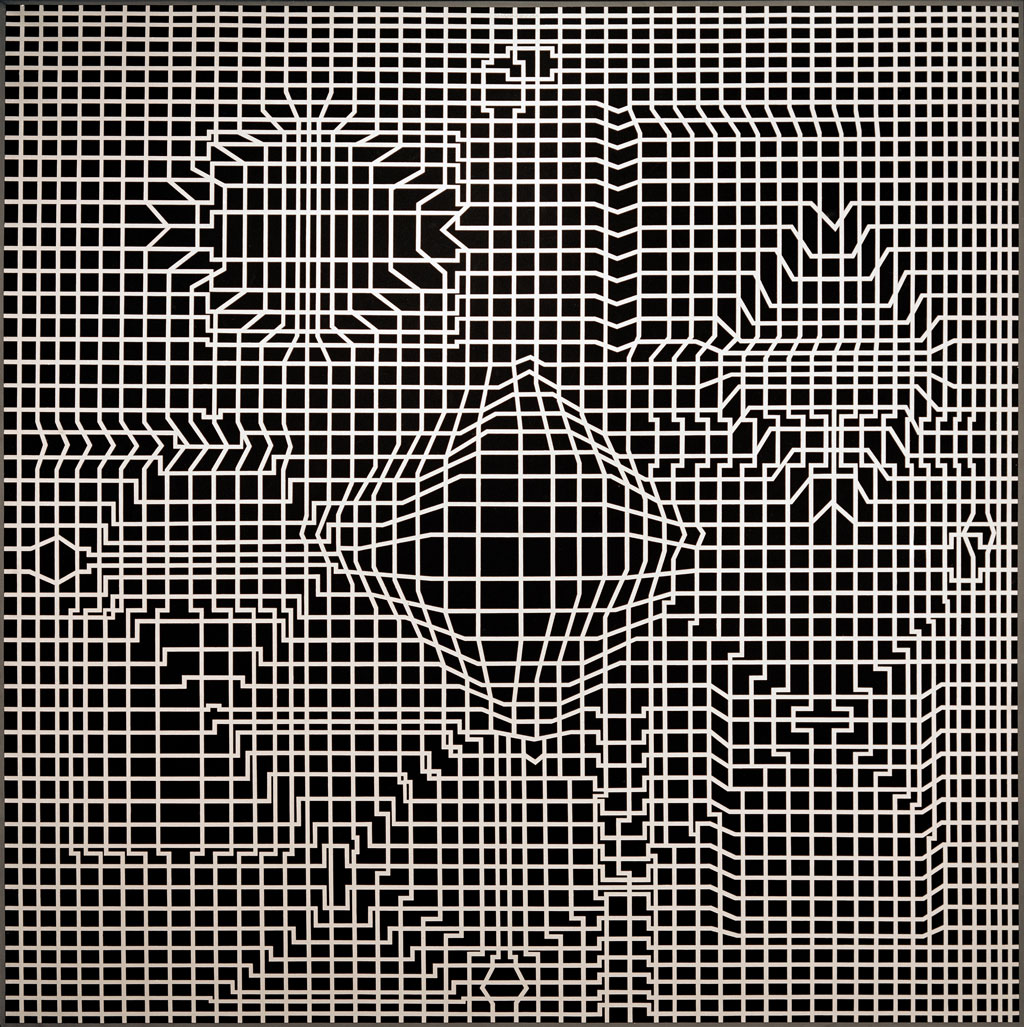

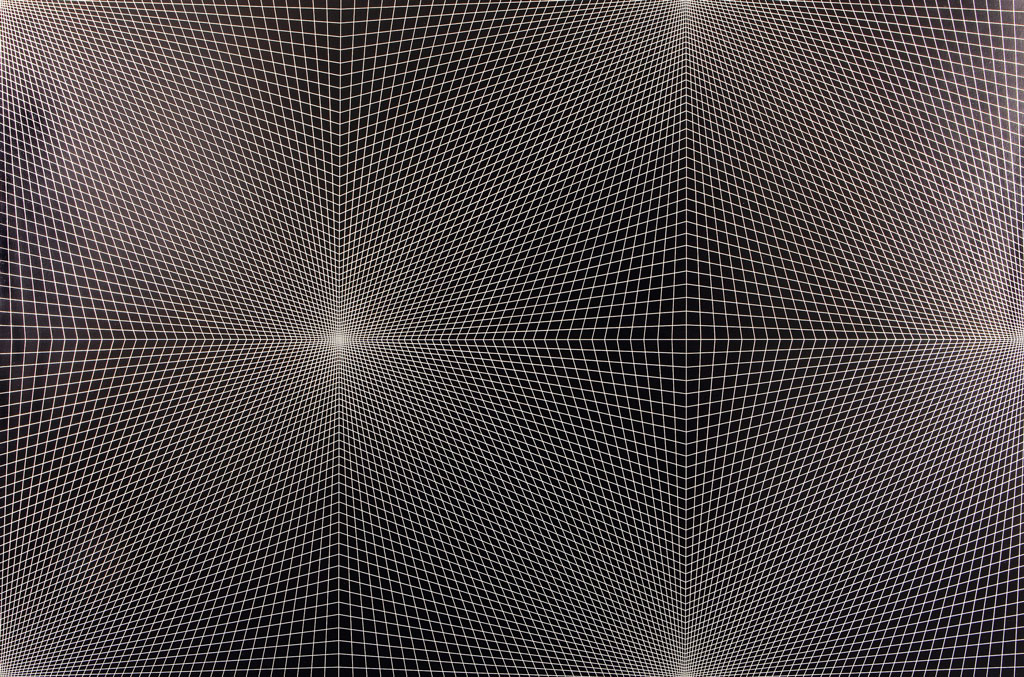

The exhibition “Vertigo. Op Art and a History of Deception 1520–1970” takes a new look at an artistic movement that first began in the mid-1950s. Ten years later, it became known as Op Art, in the run-up to a first large presentation of works at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1965. This exhibition is the first to present Op Art from the 1950s and 1960s together with much older examples from art history. Op Art’s own rejection of clarity and balance, and its assertion of movement, confusion, discomfort, and illusion corresponds to a shift from the classical to the anti-classical which can be understood in terms of a universal concept of mannerism. “Vertigo” sees Op Art as the mannerism of the concrete art of the twentieth century and compares it with examples of European mannerism from the 16th to the 18th Centuries. Around 1960 new groups of artists came together in northern Italy and France, and also in Germany and Croatia, whose aim was to explore the basic prerequisites of visual perception. They created new kinds of pictures, and they developed labyrinthine and convoluted environments that resemble fairgrounds. Their works playfully confuse viewers, and sometimes use stronger destabilizing optical stimuli to demonstrate and make people aware of the limitations of perception. The exhibition design of Vertigo draws on the idea of the labyrinth.T he labyrinth is seen as a key visual symbol of European mannerism, and as such it again became highly relevant in 1960s theory when Umberto Eco, the most significant theorist of Arte programmata, declared the unfinished and open to be key principles of art. Op artists also advocated the idea of an “open work of art”. The work is by definition unfinished both in terms of its meaning and in terms of how it interacts with viewers, and the relations between art object, artist, and receiver become a field of opportunities undergoing constant change. Op Art aims to create strong sensual reactions. It appeals not only to our vision, but also to our senses of hearing and touch, and sometimes it can affect our entire bodies in ways that lead to discomfort and disorientation. Spirals with vertiginous powers of suction, overlapping and distorted grids that lead to the Moiré effect and other pulsating patterns, ambiguous images, picture puzzles, and flicker effects are just some of the many methods and strategies that this art uses in its images, (kinetic) objects, experiential spaces, and films. The works of Op Art have no narratives or messages on offer. They are props and aids for viewers to make their own experiences. They quite literally show us the limitations of human perception, and they thereby initiate epistemological reflection. More than other works of art, they focus on the observers and create an awareness as to how far our own different sensual, psychological, and intellectual reactions are responsible for how we interpret art. Op Art works can also change their appearance depending on the observer’s vantage point, and they explicitly require that we move around when looking at them. They can also be moving works themselves, using mechanical or electric motors. The phenomenon of the after-image, for example, in which the retina is subjected to forceful intermittent stimuli, shows us that seeing is a temporal process. Current optical stimuli enter into mutual effects with the echo of images just perceived and the two meld to become a single irritating experience. This leads to an immersive and dislocating experience of space, whose parameters shift. The viewers become part of the artwork that is literally constituted in the act of perception. This also undermines the chance of contemplative viewing.

Artists: Marc Adrian, Josef Albers, Giovanni Anceschi, Richard Anuszkiewicz, Marina Apollonio, Alberto Biasi, Hartmut Böhm, Martha Boto, Gianni Colombo, Tony Conrad, Carlos Cruz-Diez, Dadamaino, Gabriele De Vecchi, Lucia di Luciano, Jean Du Breuil, Marcel Duchamp, Roland K. Fuchshuber, Giuseppe Galli-Bibiena, Heinrich Göding, Gerhard von Graevenitz, Franco Grignani, Matthias Grünewald, Brion Gysin, Athanasius Kircher, Erika Giovanna Klien, Edoardo Landi, Julio Le Parc, Adolf Luther, Enzo Mari, Almir Mavignier, Francesco Mazzola gen. Parmigianino, Claude Mellan, Richard S. Meryman, Desiderio Monsù, François Morellet, Gotthart Joe Müller, Georg Nees, Jean François Niceron, Lev Nussberg, Ivan Picelj, Helga Philipp, Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Karl Reinhartz, Circle of Guido Reni, Vjenceslav Richter, Bridget Riley, Dieter Roth, Nicolas Schöffer, Erhard Schön, Vyacheslav Shcherbakov, Lorenz Stör, Jesús Rafael Soto, Aleksandar Srnec, Kerry Strand, Paul Talman, Abbott Handerson Thayer, Hans Tröschel, Gracia Varisco, Victor Vasarely, After Johann Christian Vollaert, Hans Vredeman de Vries, Edward Wadsworth, James Whitney and Ludwig Wilding

Info: Curators: Eva Badura-Triska and Markus Wörgötter, Mumok (museum moderner kunst stiftung ludwig wien), Museumsplatz 1, Vienna, Duration: 25/5-26/10/19, Days & Hours: Mon 14:00-19:00, Tue-Wed & Fri-Sun 10:00-19:00, Thu 10;00-21:00, www.mumok.at