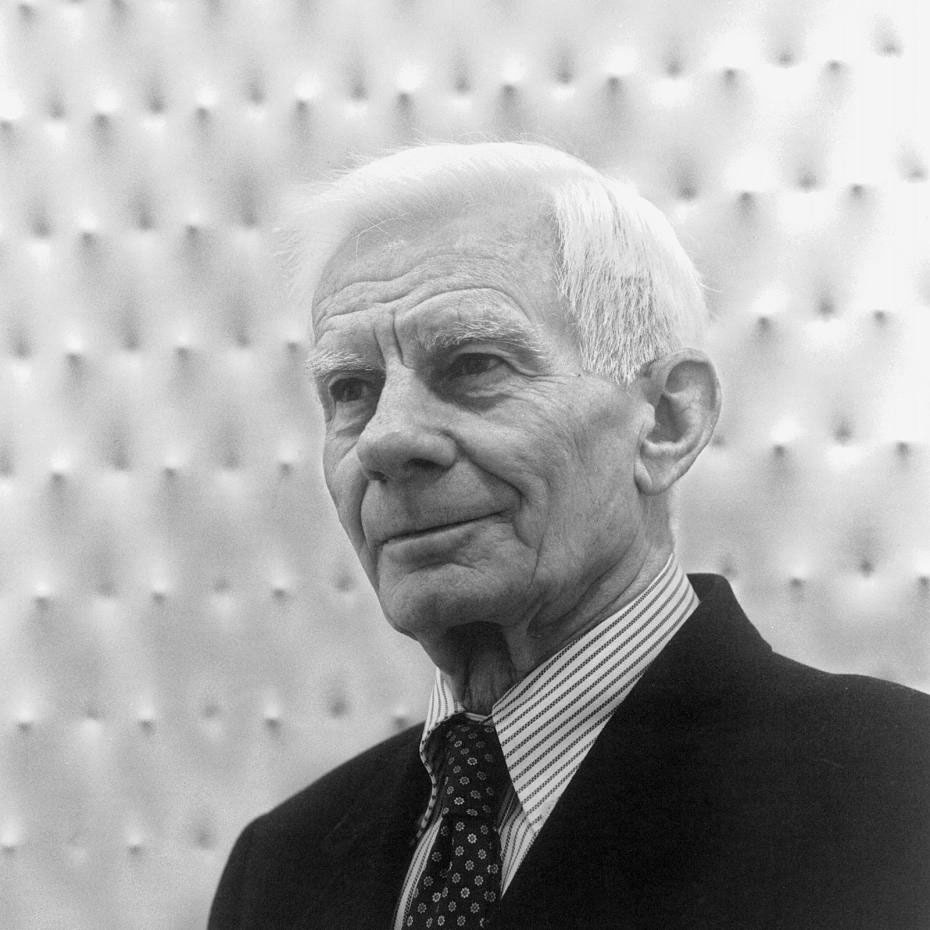

TRACES: Enrico Castellani

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Enrico Castellani (4/8/1930-1/12/2017), one of Italy’s most influential artists associated with the zero movement, Movimento Arte Nucleare and Azimut and is best known for his “paintings of light”. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Enrico Castellani (4/8/1930-1/12/2017), one of Italy’s most influential artists associated with the zero movement, Movimento Arte Nucleare and Azimut and is best known for his “paintings of light”. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Efi Michalarou

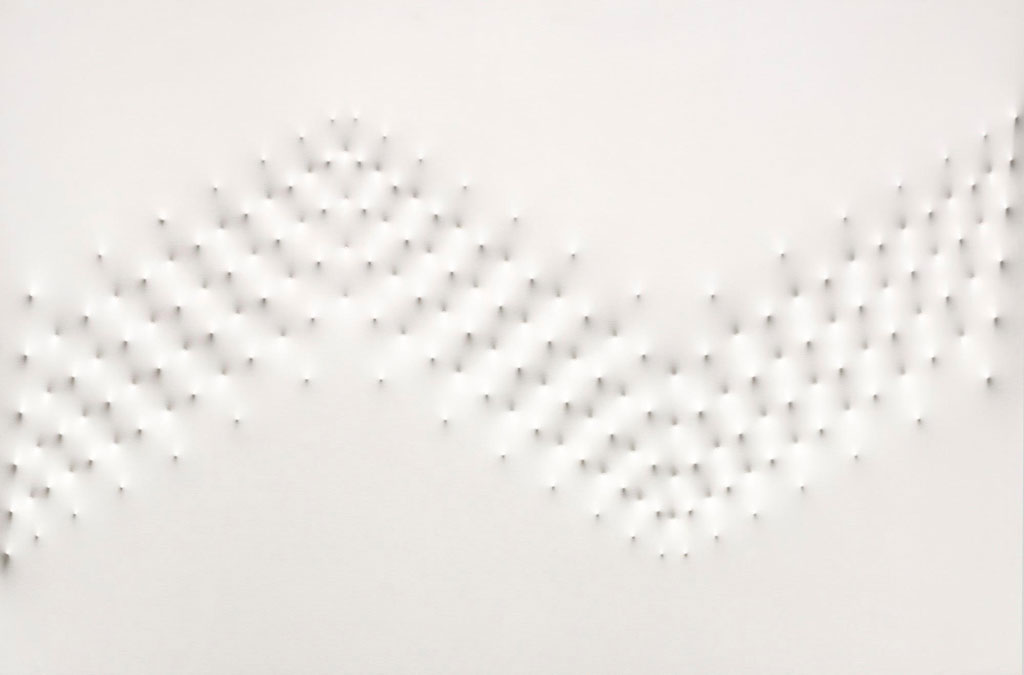

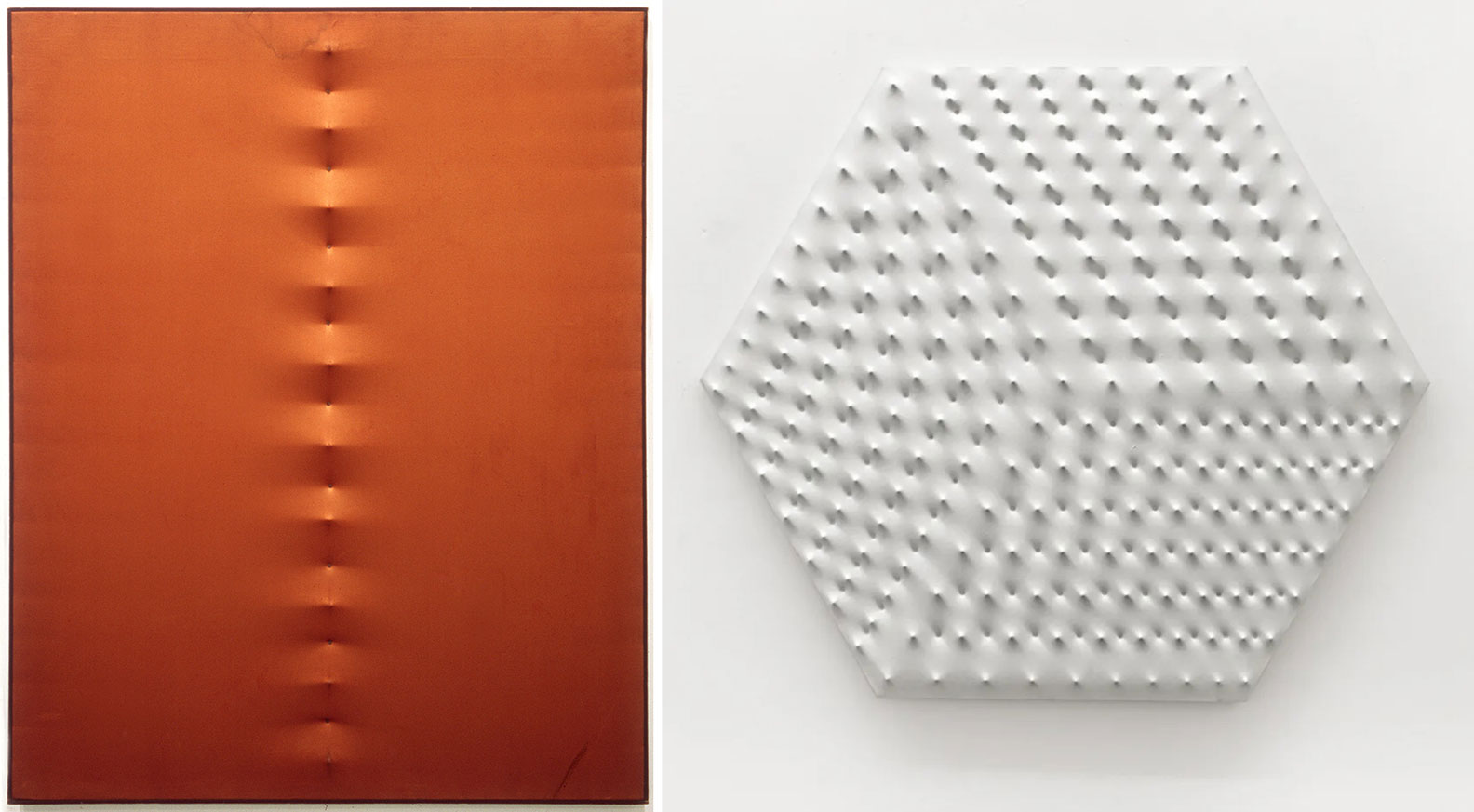

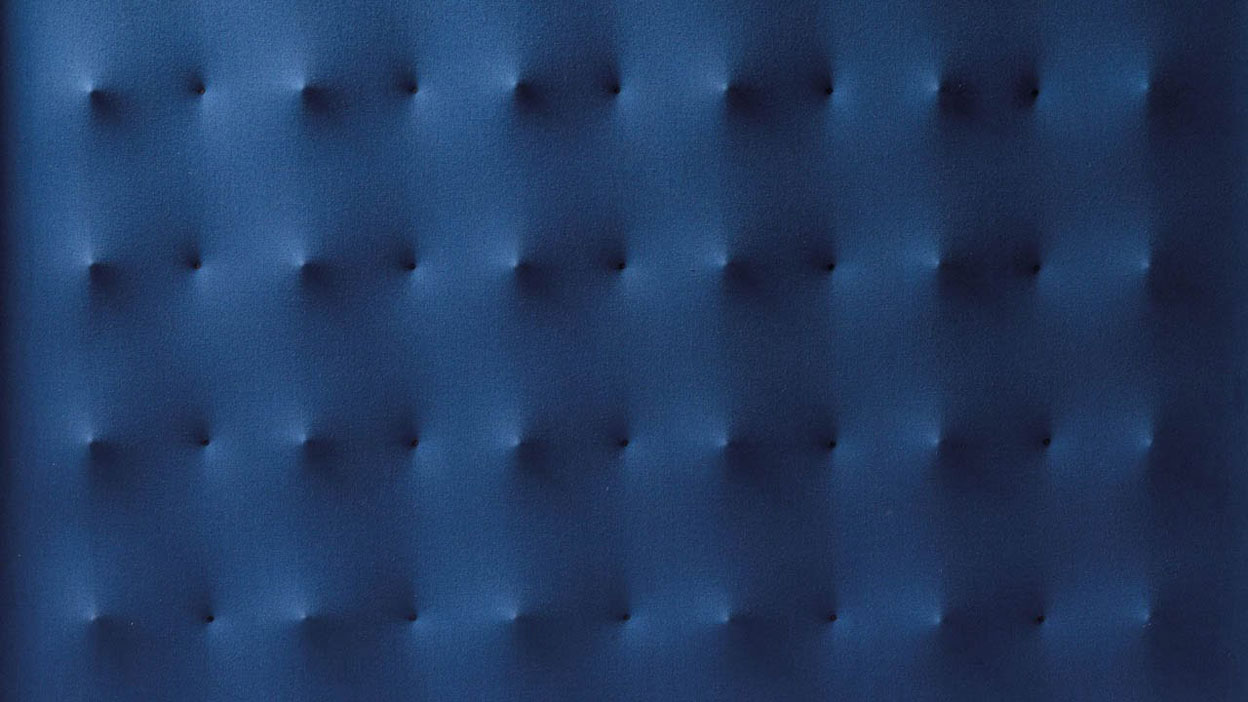

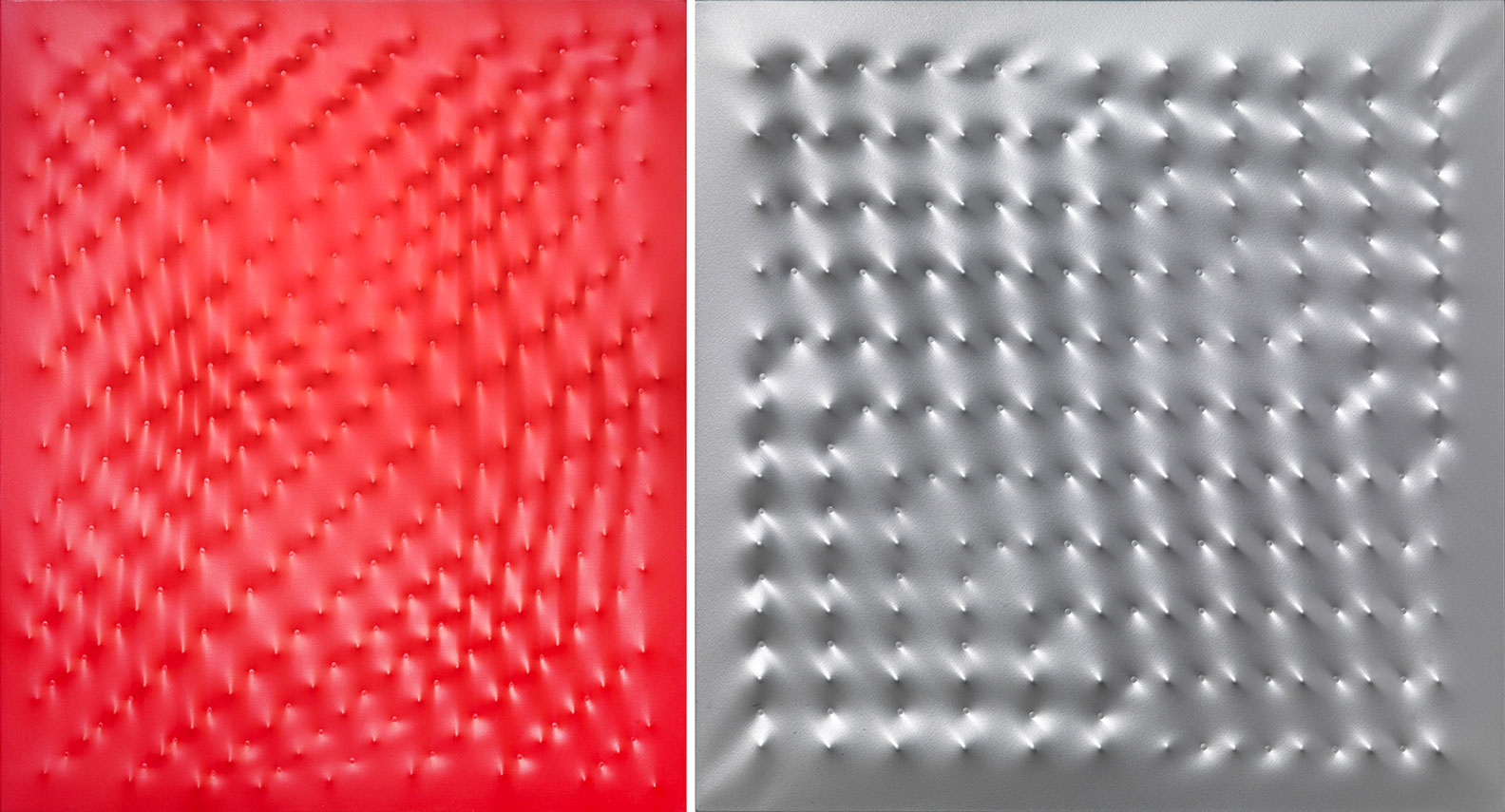

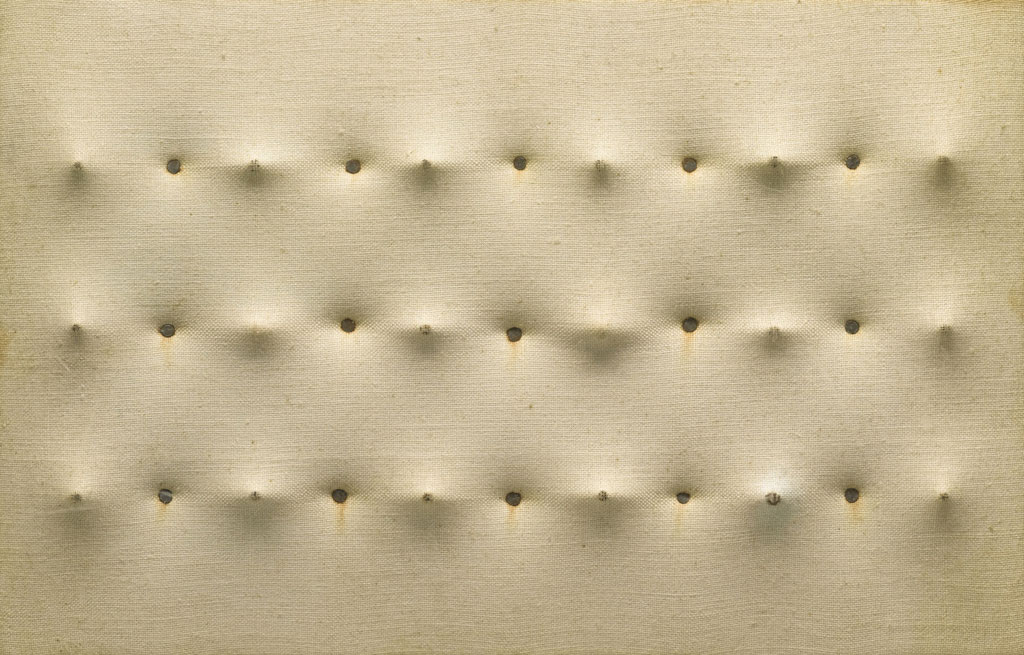

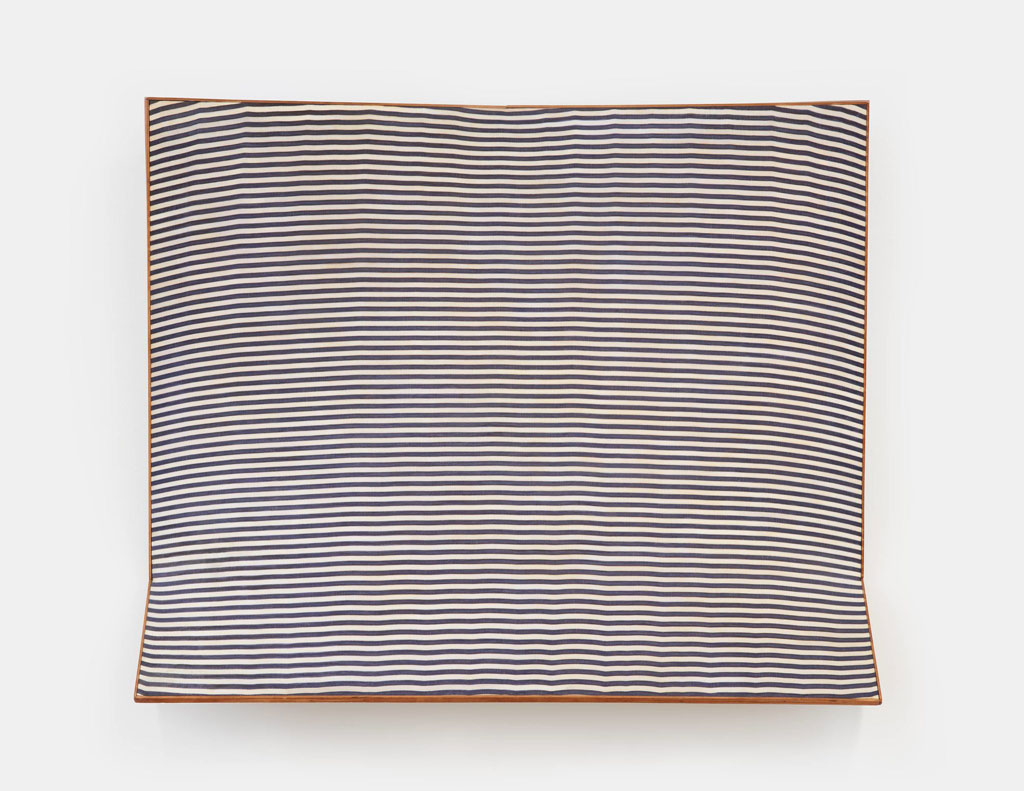

Enrico Castellani was born in the town of Castelmassa, around 60 miles southwest of Venice. As a young man he moved to Belgium, and after initial courses in painting and sculpture, he graduated in architecture at the École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Visuels de la Cambre, in Brussels. He returned to Italy in the mid-1950s and worked for a few years in the studio of architect Franco Buzzi in Milan. Despite his architectural training, he painted at night and weekends and spent a lot of time at a restaurant called Trattoria all’Oca d’Oro, whose owner was happy for artists such as Castellani and his friends, Piero Manzoni and Lucio Fontana, to pay for their food with the occasional art work. Castellani was greatly influenced by the German art group ZERO, formed by artists Heinz Mack, Otto Piene, and Günther Uecker. In December 1959, Castellani and Piero Manzoni opened a gallery in Milan called Azimut, at the same time as launching an affiliate magazine, Azimuth, two short-lived but significant ventures dedicated to redefining art as people knew it. The gallery would hold 13 exhibitions in total, including three by Manzoni and one by Castellani (his debut show). In the same period he joined the group Zero and Nul. Where Fontana broke new ground by slashing his canvases with a knife, and Manzoni did so by soaking his in kaolin solution, Castellani created monochromatic reliefs by driving nails into the underlying frames of his canvases at varying depths, and then painting on top in a single colour. This type of work, known as his “Superfici” became Castellani’s trademark. Castellani has spent decades trying out his ‘Superfici”in different permutations. One of these is to vary the color of his paint, as well as white, he has used yellow, black, blue and, in works such as “Superficie Rossa, red”. A handful of works painted in silver, such as “Superficie Alluminio” are distinguished by their captivating metallic sheen. Other variations include changing the shape of his canvases to triangular and rhomboid. Where he had started out applying the nails in grid-like form, over time he was also much more flexible about the intervals at which they appeared, he arranged his nails into diagonal vectors that form corridors of open space which alternately narrow and widen across the canvas. He exhibited, in 1961, at the Turtle Gallery of Rome (and again in 1965, 1966, 1970, 1974), while in 1962 at the Galerie d’Aujourd’hui Brussels, and in 1963 at the gallery dell’Ariete Milan, where he returned to exhibit in 1972. From 1963 to 1970 the surface poetry gave way to the subject and the artist’s attention focuses on the study of formal articulations of the surface: canvases are shaped, angular, diptychs and triptychs. In 1966 he won the Gollin prize at the Venice Biennale. The same year he exhibited again at the Gallery News in Turin, at the Betty Parsons Gallery in New York and Tokyo Gallery in Tokyo. In 1970 he exhibited at the M Gallery, Bochum. He showed at the Form Gallery in Genoa in 1972. Castellani influenced a number of artists and movements who came after him, perhaps most notably Minimalism. Donald Judd singled him out for praise in “Specific Objects” his seminal treatise on the Minimalist movement. The Italian, however, has never revelled in the limelight, preferring his work to speak for itself. Over the years, Castellani has designed sets for theatre and ballet productions. In a similar vein, he has also created room-sized installations he calls “Environments”, which involve placing a number of his works strategically about a gallery. such cases, his art went beyond the conventional bounds of painting into a new spatial dimension that harked back to his roots in architecture. During the 1980s and ’90s his work continued to develop the over-stretched, protruding technique, within an idea that critics wanted to define as “different repetition”.

Enrico Castellani was born in the town of Castelmassa, around 60 miles southwest of Venice. As a young man he moved to Belgium, and after initial courses in painting and sculpture, he graduated in architecture at the École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Visuels de la Cambre, in Brussels. He returned to Italy in the mid-1950s and worked for a few years in the studio of architect Franco Buzzi in Milan. Despite his architectural training, he painted at night and weekends and spent a lot of time at a restaurant called Trattoria all’Oca d’Oro, whose owner was happy for artists such as Castellani and his friends, Piero Manzoni and Lucio Fontana, to pay for their food with the occasional art work. Castellani was greatly influenced by the German art group ZERO, formed by artists Heinz Mack, Otto Piene, and Günther Uecker. In December 1959, Castellani and Piero Manzoni opened a gallery in Milan called Azimut, at the same time as launching an affiliate magazine, Azimuth, two short-lived but significant ventures dedicated to redefining art as people knew it. The gallery would hold 13 exhibitions in total, including three by Manzoni and one by Castellani (his debut show). In the same period he joined the group Zero and Nul. Where Fontana broke new ground by slashing his canvases with a knife, and Manzoni did so by soaking his in kaolin solution, Castellani created monochromatic reliefs by driving nails into the underlying frames of his canvases at varying depths, and then painting on top in a single colour. This type of work, known as his “Superfici” became Castellani’s trademark. Castellani has spent decades trying out his ‘Superfici”in different permutations. One of these is to vary the color of his paint, as well as white, he has used yellow, black, blue and, in works such as “Superficie Rossa, red”. A handful of works painted in silver, such as “Superficie Alluminio” are distinguished by their captivating metallic sheen. Other variations include changing the shape of his canvases to triangular and rhomboid. Where he had started out applying the nails in grid-like form, over time he was also much more flexible about the intervals at which they appeared, he arranged his nails into diagonal vectors that form corridors of open space which alternately narrow and widen across the canvas. He exhibited, in 1961, at the Turtle Gallery of Rome (and again in 1965, 1966, 1970, 1974), while in 1962 at the Galerie d’Aujourd’hui Brussels, and in 1963 at the gallery dell’Ariete Milan, where he returned to exhibit in 1972. From 1963 to 1970 the surface poetry gave way to the subject and the artist’s attention focuses on the study of formal articulations of the surface: canvases are shaped, angular, diptychs and triptychs. In 1966 he won the Gollin prize at the Venice Biennale. The same year he exhibited again at the Gallery News in Turin, at the Betty Parsons Gallery in New York and Tokyo Gallery in Tokyo. In 1970 he exhibited at the M Gallery, Bochum. He showed at the Form Gallery in Genoa in 1972. Castellani influenced a number of artists and movements who came after him, perhaps most notably Minimalism. Donald Judd singled him out for praise in “Specific Objects” his seminal treatise on the Minimalist movement. The Italian, however, has never revelled in the limelight, preferring his work to speak for itself. Over the years, Castellani has designed sets for theatre and ballet productions. In a similar vein, he has also created room-sized installations he calls “Environments”, which involve placing a number of his works strategically about a gallery. such cases, his art went beyond the conventional bounds of painting into a new spatial dimension that harked back to his roots in architecture. During the 1980s and ’90s his work continued to develop the over-stretched, protruding technique, within an idea that critics wanted to define as “different repetition”.