TRACES: Donald Judd

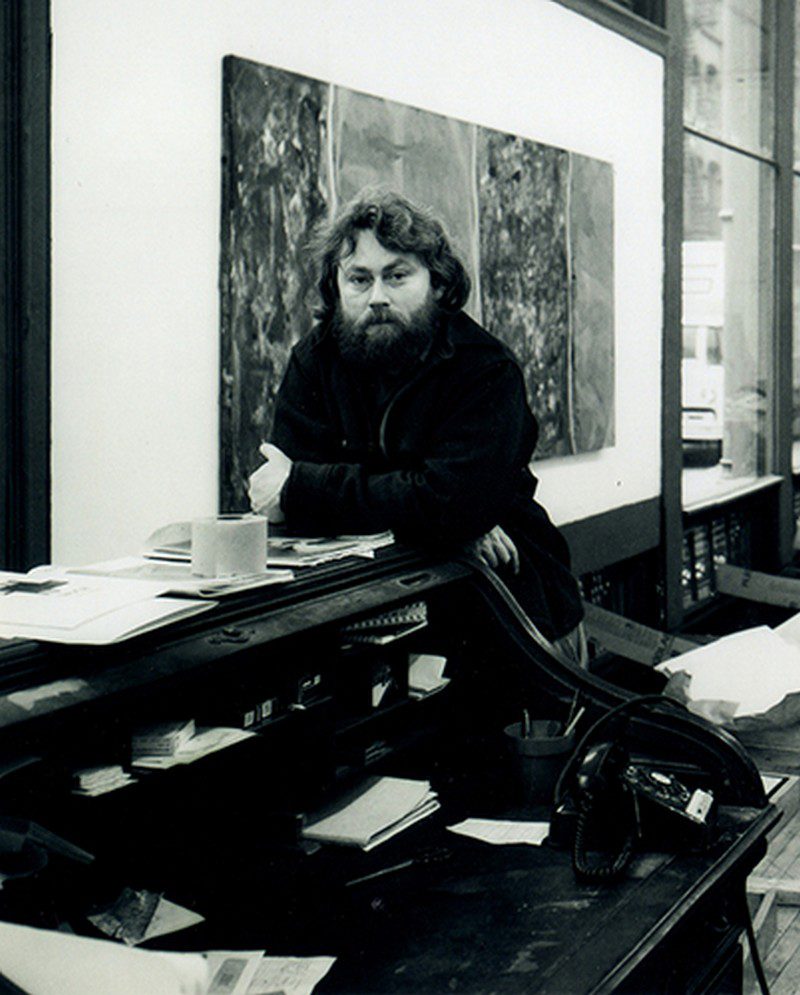

Today is the occasion to bear in mind the American artist Donald Judd (3/6/1928-12/2/1994), associated with Minimalism. In his work, Judd sought autonomy and clarity for the constructed object and the space created by it. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind the American artist Donald Judd (3/6/1928-12/2/1994), associated with Minimalism. In his work, Judd sought autonomy and clarity for the constructed object and the space created by it. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Dimitris Lempesis

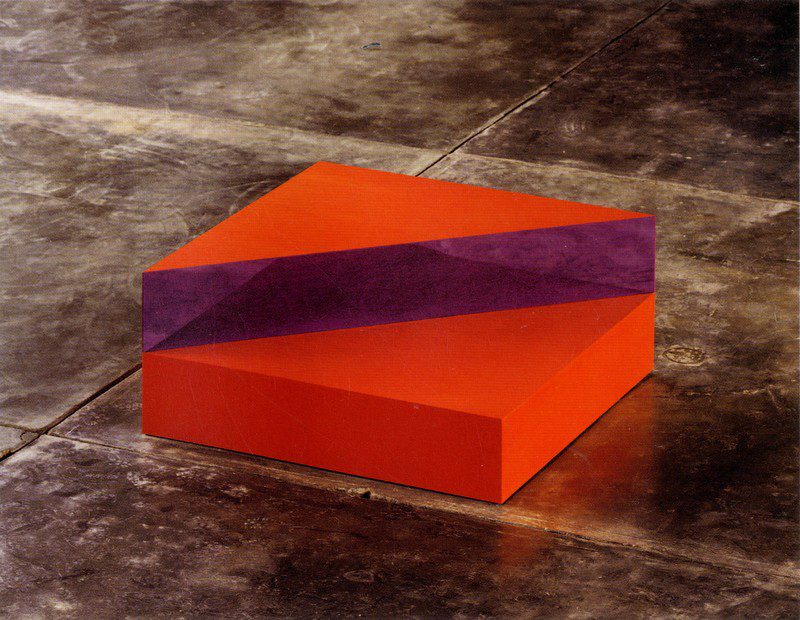

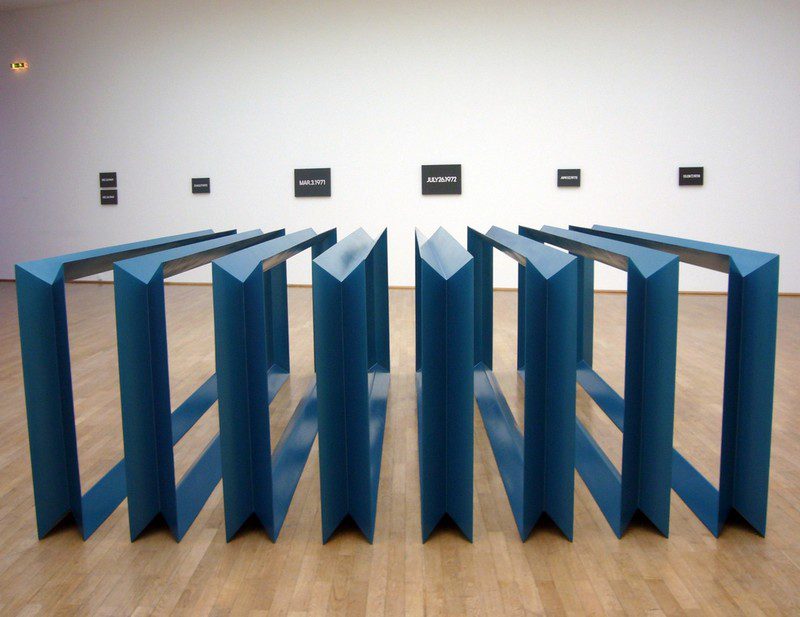

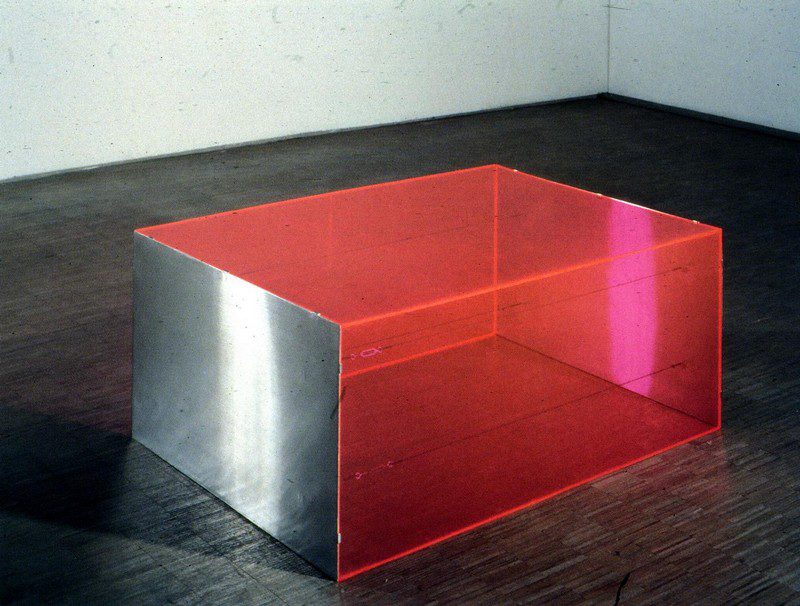

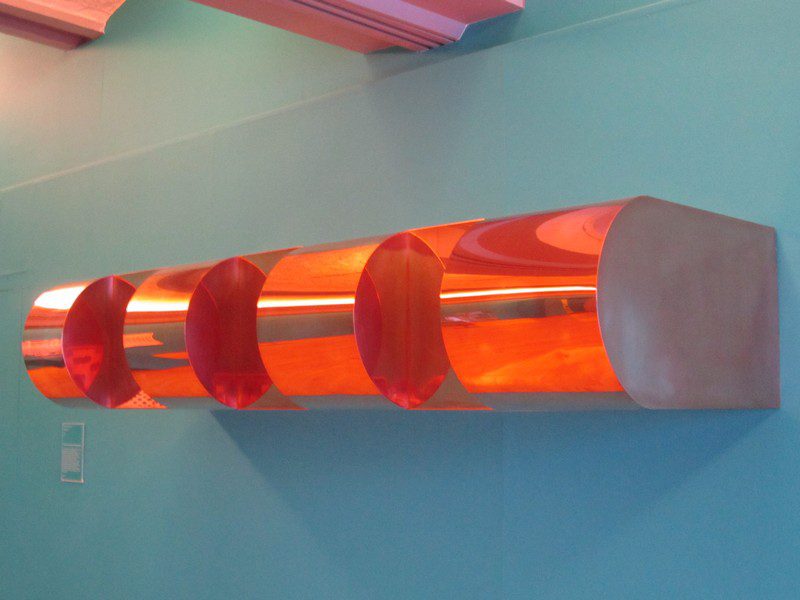

Donald Clarence Judd, he entered the College of William and Mary in 1948, he earned a bachelor’s degree in philosophy from Columbia and studied painting at the Art Students League in New York. He began his career as a painter, drawing on the work of the abstract Expressionists, but as time went on he became increasingly dissatisfied with painting, a medium that he came to believe was a thing of the past. In the late 1950s and early 1960s he established a reputation as an art critic, arguing that painting was, in his word, “finished.” Instead, he championed the new generation of Post-Abstract Expressionist Artists, such as John Chamberlain, Claes Oldenburg, and Frank Stella, whose work was moving away from what he viewed as outmoded European aesthetic ideals. Judd was particularly taken by the notion that art no longer had a representational purpose, he maintained that what mattered in a work of art was its own formal qualities-shape, color, surface, volume. As he abandoned painting for sculpture in the early 1960s, he wrote the manifesto-like essay “Specific Objects” in 1964.In his essay, Judd found a starting point for a new territory for American Art, and a simultaneous rejection of residual inherited European artistic values, these values being illusion and represented space, as opposed to real space. During the early 1960s he began making his own sculptures-boxes, ramps, and open geometric objects-many of them painted his favorite color, cadmium light red. His precisely made cubic and rectilinear works were instrumental in setting a new course for American sculpture and eventually established him as a leading figure in the Minimal Art movement. Judd combined the use of highly finished, industrialized materials, such as iron, steel, plastic, and Plexiglas – techniques and methods associated with the Bauhaus School, to give his works an impersonal, factory aesthetic. This served to separate his pieces from those of the Abstract Expressionists, whose emphasis on the artist’s touch gave their images a confessional, personal context. Judd’s work, however, also brought sharp criticisms from conservative members of the art establishment. Judd responded to such charges by arguing, in his typically deadpan style, that “Art need only be interesting” and that it was “Something you look at”. In the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, Judd had solo shows at a number of leading museums and galleries. Judd was also a Guggenheim Foundation fellow in 1968 and a National Endowment for the Arts grantee in 1967 and 1976. In his later years he tried his hand at designing furniture and architecture, using the same simple formal language he employed in his sculpture. In the early 1970s Judd acquired a 45,000-acre ranch overlooking the Rio Grande in West Texas and purchased a number of buildings in and around Marfa, including the barracks, hangars, and gymnasium of an abandoned army base, Fort D. A. Russell. He converted the hangars into massive galleries for contemporary art and refurbished some of the other structures to serve as work, office, and storage spaces.

Donald Clarence Judd, he entered the College of William and Mary in 1948, he earned a bachelor’s degree in philosophy from Columbia and studied painting at the Art Students League in New York. He began his career as a painter, drawing on the work of the abstract Expressionists, but as time went on he became increasingly dissatisfied with painting, a medium that he came to believe was a thing of the past. In the late 1950s and early 1960s he established a reputation as an art critic, arguing that painting was, in his word, “finished.” Instead, he championed the new generation of Post-Abstract Expressionist Artists, such as John Chamberlain, Claes Oldenburg, and Frank Stella, whose work was moving away from what he viewed as outmoded European aesthetic ideals. Judd was particularly taken by the notion that art no longer had a representational purpose, he maintained that what mattered in a work of art was its own formal qualities-shape, color, surface, volume. As he abandoned painting for sculpture in the early 1960s, he wrote the manifesto-like essay “Specific Objects” in 1964.In his essay, Judd found a starting point for a new territory for American Art, and a simultaneous rejection of residual inherited European artistic values, these values being illusion and represented space, as opposed to real space. During the early 1960s he began making his own sculptures-boxes, ramps, and open geometric objects-many of them painted his favorite color, cadmium light red. His precisely made cubic and rectilinear works were instrumental in setting a new course for American sculpture and eventually established him as a leading figure in the Minimal Art movement. Judd combined the use of highly finished, industrialized materials, such as iron, steel, plastic, and Plexiglas – techniques and methods associated with the Bauhaus School, to give his works an impersonal, factory aesthetic. This served to separate his pieces from those of the Abstract Expressionists, whose emphasis on the artist’s touch gave their images a confessional, personal context. Judd’s work, however, also brought sharp criticisms from conservative members of the art establishment. Judd responded to such charges by arguing, in his typically deadpan style, that “Art need only be interesting” and that it was “Something you look at”. In the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, Judd had solo shows at a number of leading museums and galleries. Judd was also a Guggenheim Foundation fellow in 1968 and a National Endowment for the Arts grantee in 1967 and 1976. In his later years he tried his hand at designing furniture and architecture, using the same simple formal language he employed in his sculpture. In the early 1970s Judd acquired a 45,000-acre ranch overlooking the Rio Grande in West Texas and purchased a number of buildings in and around Marfa, including the barracks, hangars, and gymnasium of an abandoned army base, Fort D. A. Russell. He converted the hangars into massive galleries for contemporary art and refurbished some of the other structures to serve as work, office, and storage spaces.