ART CITIES:Los Angeles-Bauhaus Beginnings

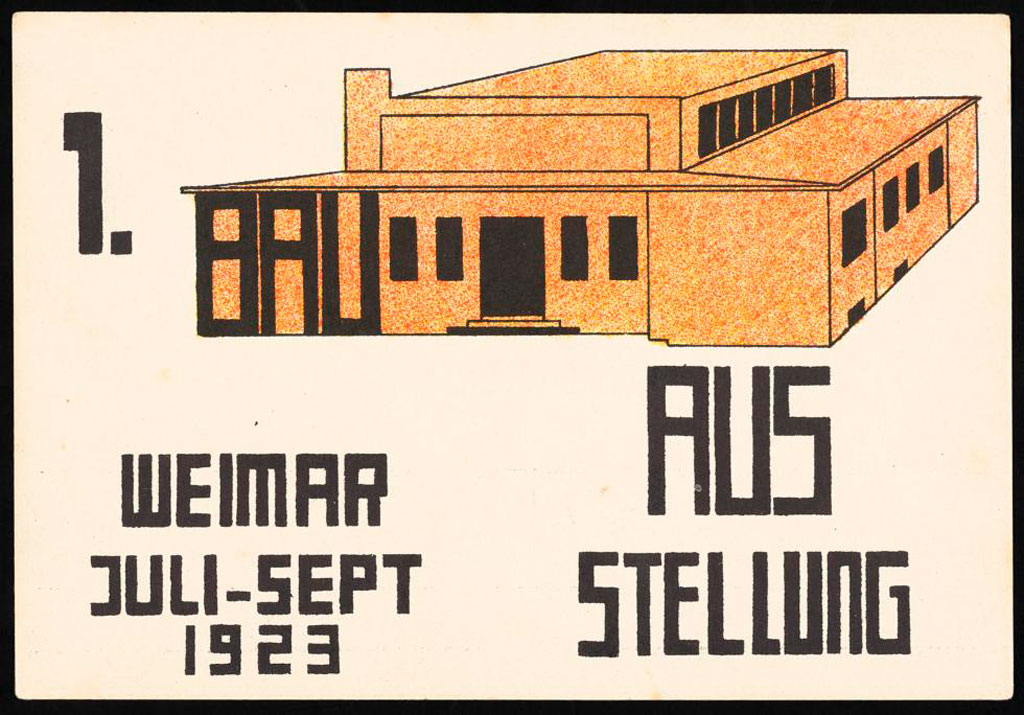

The Bauhaus is widely regarded as the most influential school of art and design of the 20th Century. Marking the 100th anniversary of the school’s opening, the exhibition “Bauhaus Beginnings”examines the founding principles of the landmark institution. The archives are rich in rare prints, drawings, photographs, and other materials from some of the most famous artists to work at Bauhaus as well as students whose work, while lesser known, is extremely compelling and sometimes astonishing.

The Bauhaus is widely regarded as the most influential school of art and design of the 20th Century. Marking the 100th anniversary of the school’s opening, the exhibition “Bauhaus Beginnings”examines the founding principles of the landmark institution. The archives are rich in rare prints, drawings, photographs, and other materials from some of the most famous artists to work at Bauhaus as well as students whose work, while lesser known, is extremely compelling and sometimes astonishing.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Getty Research Institute Archive

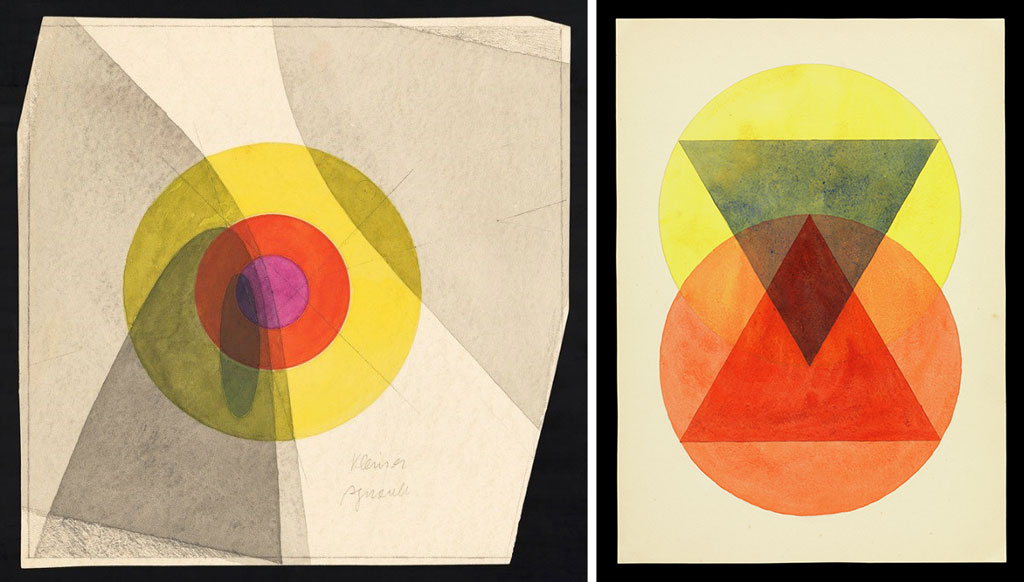

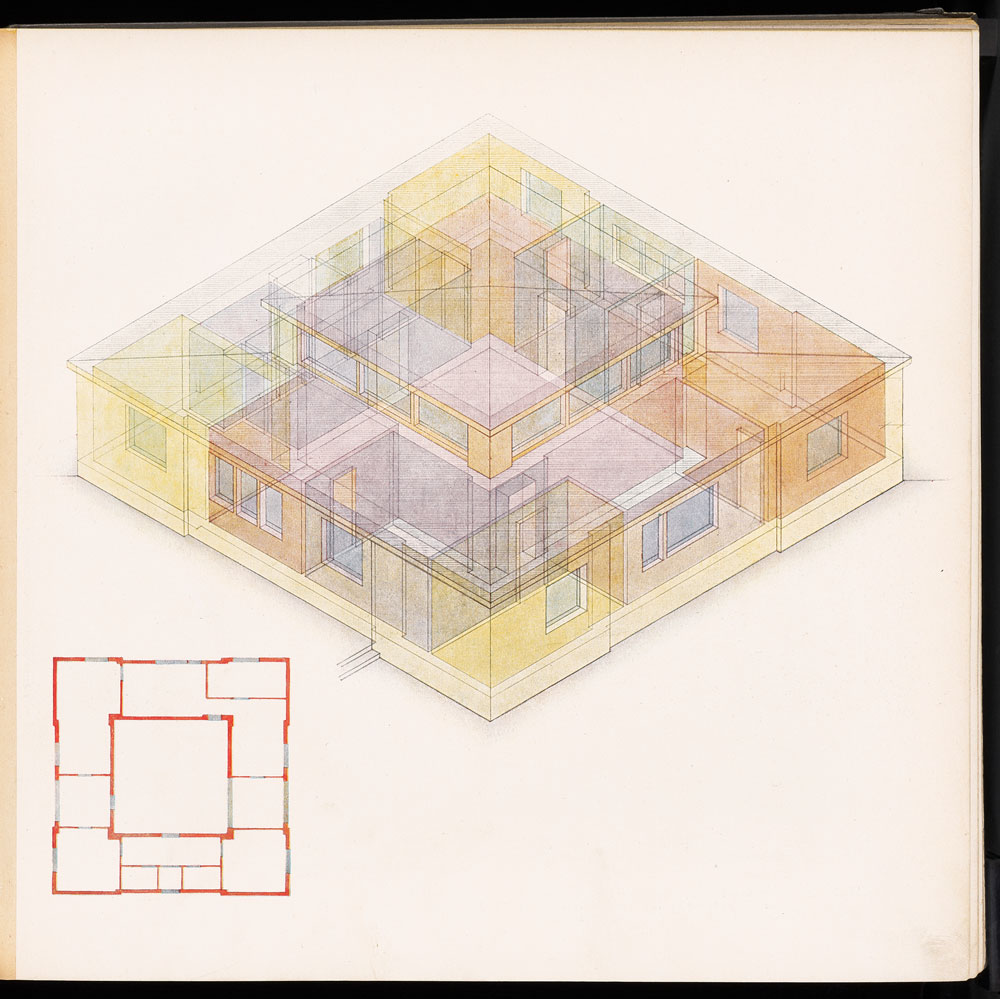

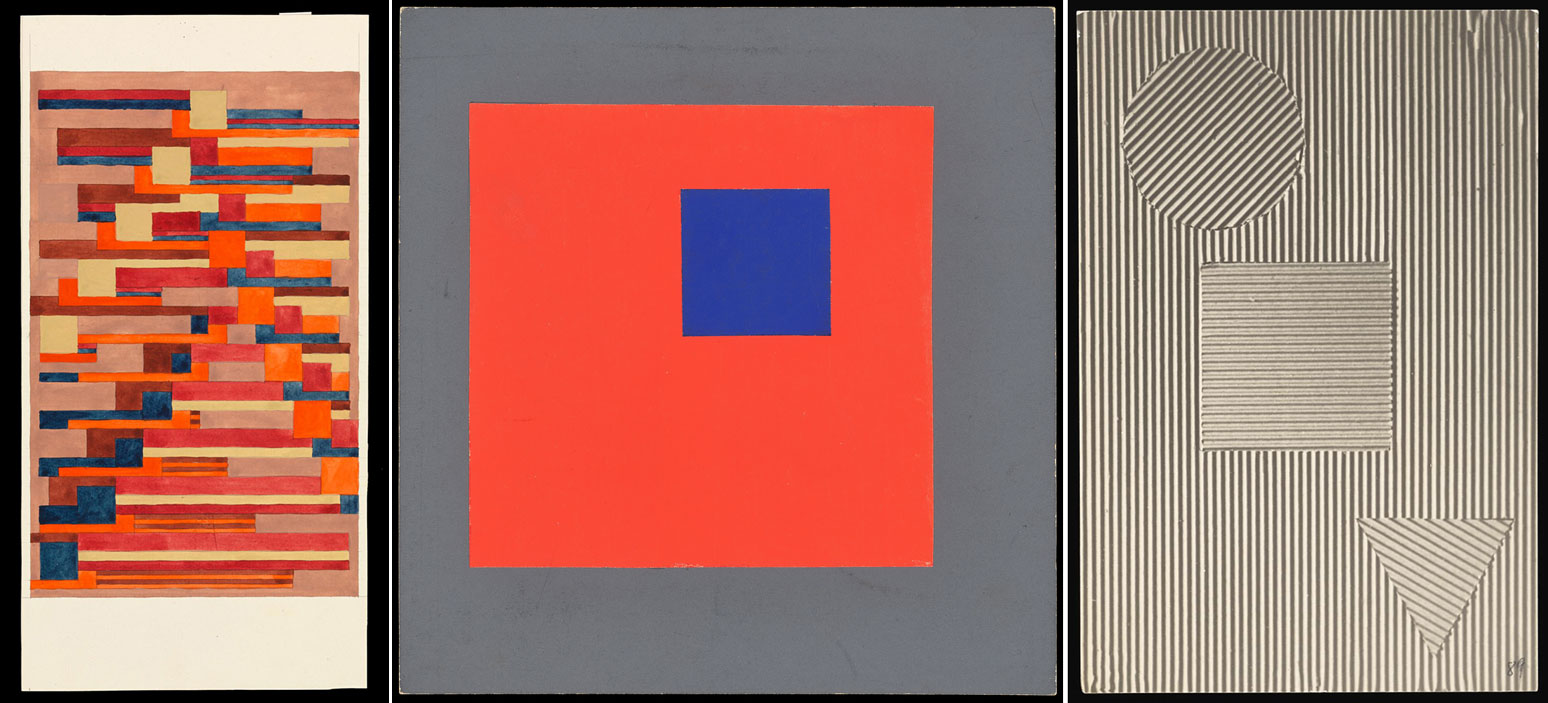

Established in 1919 after the end of World War I, the Bauhaus sought to erode distinctions between crafts and the fine arts through a program of study centered on theory and practical experience. The idea at the center of Bauhaus practice was Gesamtkunstwerk (the total work of art). In 1919 Walter Gropius widely circulated a manifesto, illustrated with a woodcut by Lyonel Feininger, that announced his bold vision for the newly reformed, state-sponsored school of design and the model of education that would bridge the fine and applied arts. In the text, on view in the exhibition, Gropius outlined how uniting various forms of practices, especially painting, sculpture, architecture, and design, would produce socially and spiritually gratifying works of art. Feininger’s woodcut of a preindustrial Gothic cathedral represented the total work of art, in which designers, artists, and artisans worked together in service of a spiritual goal. In early 1920, an opportunity to realize a Gesamtkunstwerk “building of the future”, an ideal set forth in the Bauhaus manifesto, presented itself. Adolf Sommerfeld, a lumber mill owner, building contractor, and real estate developer specializing in timber structures commissioned Walter Gropius and Adolf Meyer to design a residence in the south of Berlin. Gropius recognized the opportunity to bring the various Bauhaus workshops together in the design of the house, which took inspiration from a rustic log cabin. Students from the various workshops designed key elements of the interior, including a large stained-glass window above the staircase, carved wood ornaments, a large curtain, a set of wooden tables and chairs, light fixtures, radiator covers, rugs, and wall hangings. The exhibition also explores the Preliminary Course at the Bauhaus which introduced all first-year students to what were considered the fundamental principles of color, form, and material. Various Bauhaus masters led these first-year studies: after Johannes Itten initiated the Preliminary Course in the fall of 1920, László Moholy-Nagy and Josef Albers took over beginning in 1923. These courses were supplemented by specialized theoretical seminars led by important Bauhaus faculty, including Gertrud Grunow, Vassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Joost Schmidt and Oskar Schlemmer. Despite their many ideological differences, the masters agreed that a firm grounding in the principles of form and color achieved through practical exercises was crucial to the development of a new class of artists. Masters’ teaching aids and student exercises in the exhibition demonstrate how color theory remained a central focus at the Bauhaus throughout the school’s fourteen-year existence. Committed to understanding the nature of colors, instructors and students produced countless graphic systems of wheels, triangles, grids, and spheres to examine how colors relate to one another. Though women were admitted to the Bauhaus in relatively large numbers (in 1919, 59 out of 139 enrolled students were women) they did not enjoy equal status with the male students. Despite many objections, the majority of women students were pushed to study weaving rather than other media such as metal-working or architecture after completing the Preliminary Course. The products produced in the weaving workshop were some of the most successful and financially viable at the Bauhaus. In the aftermath of the war, materials and funds for the school’s workshops were scarce, and the weavers used looms held over from Van de Velde’s School of Applied Arts to produce artisanal, yet popular, one-off objects such as stuffed animals and dolls. Early Bauhaus master Helene Börner instructed weaving students to draw upon foundational theories of color and form developed in the Preliminary Course to produce innovative designs. When former student Gunta Stölzl became director of the weaving workshop in 1926, she argued that “a woven piece is always a serviceable object” pushing production away from the loom and toward industrial modes. Bauhaus textiles were manufactured in bulk and sold widely, rendering them one of the most successful and broadly disseminated Bauhaus products. The exhibition features textile samples as well as watercolor and other studies for textiles.

Info: Curator: Maristella Casciato, Assistant Curators: Gary Fox, Katherine Rochester, Alexandra Sommer, and Johnny Tran, Getty Research Institute, Getty Center Los Angeles, 1200 Getty Center Drive, Los Angeles, Duration: 11/6-13/10/19, Days & Hours: Tue-Fri & Sun 10:00-17:30, sat 10:00-21:00, www.getty.edu