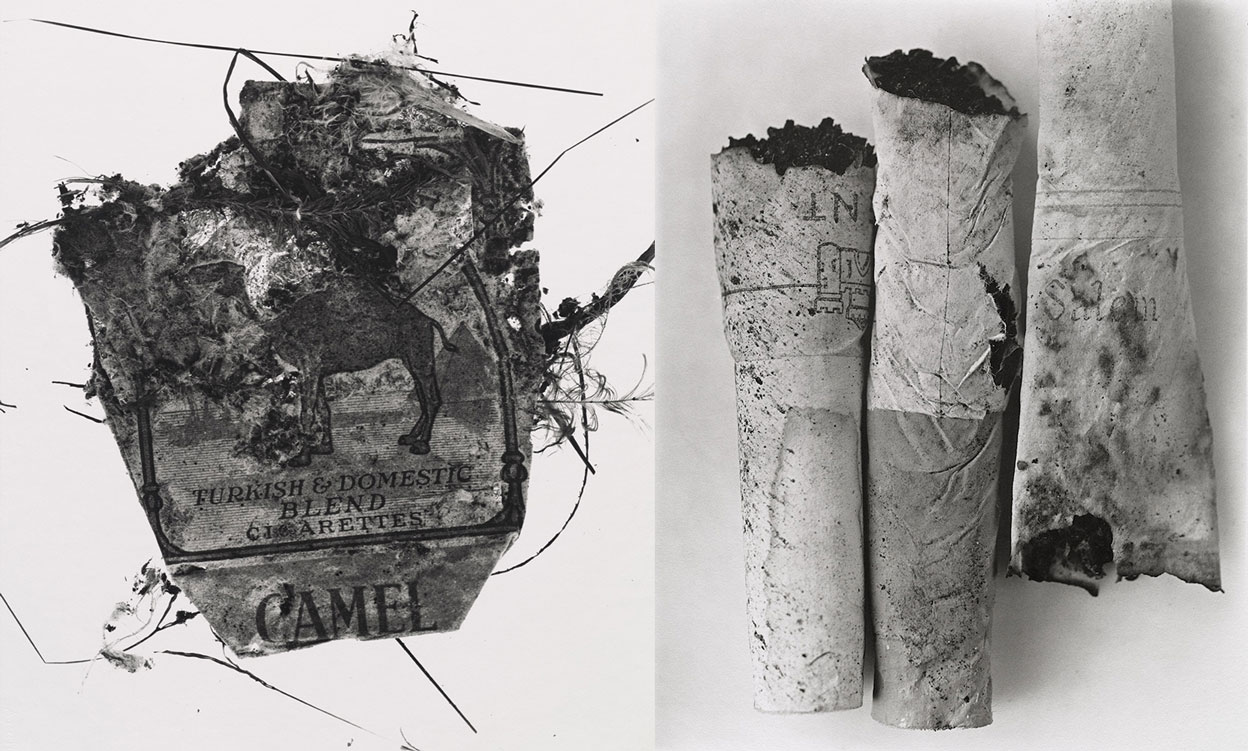

Photo:Irving Penn-Still Life

Irving Penn was one of the most important and influential photographers of the 20th Century. In a career that spanned almost 70years, Penn worked on professional and art projects across multiple genres. He was a master printer of both black-and-white and color photography and published more than 9 books of his photographs and two of his drawings during his lifetime.

Irving Penn was one of the most important and influential photographers of the 20th Century. In a career that spanned almost 70years, Penn worked on professional and art projects across multiple genres. He was a master printer of both black-and-white and color photography and published more than 9 books of his photographs and two of his drawings during his lifetime.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac

The exhibition “Still Life” is devoted to Irving Penn’s still lifes, including the well-known series “Street Material”, “Cigarettes” and “Flowers”. The exhibition features over 30 photographs taken in New York over six decades for publications such as Vogue, as well as on his travels. Irving Penn created some of the most memorable still lifes of our time, and his innovative portraits, still lifes, fashion and beauty photographs made his reputation as one of the most high-profile and influential photographers of the 20th Century. Irving Penn began his career as a photographer in 1943 at the suggestion and with the encouragement of Alexander Liberman, then art director of US Vogue. The same year, one of Irving Penn’s color photographs for Vogue appeared on the cover of their October issue, showing the first photographic still life in the magazine’s recent history. In the ensuing 60 years, he produced pioneering editorials, which became known for their natural lighting and formal simplicity, making him the leading photographer in the field. At a time when photography was understood primarily as a means of communication, Irving Penn approached it with an artist’s eye, expanding its creative potential in both his professional and his personal work. Many of Irving Penn’s still lifes combine food with everyday objects. He staged laid tables with exquisite arrangements of dishes, fruit and vessels, reminiscent of the Dutch masters of the Golden Age like Willem Kalf or Pieter Claesz. A cut-open watermelon, a crumpled linen table-napkin, a broken-off piece of baguette or a fly sitting on ripe fruit relate to the transience symbolized in vanitas paintings and emphasise the absence of the human being. The individual states of decay illustrated in the “Cigarettes” photographs show an interesting correlation with human characteristics, and may also be interpreted as memento mori. When Irving Penn first exhibited his photographs of cigarette butts at the Marlborough Gallery in New York City in 1975, the “Cigarettes” were met with incomprehension. Why make achingly beautiful prints of something beneath regard? Two decades earlier, in the 1950s when smoking was socially acceptable, Penn had made portraits of people smoking and ads for cigarettes. But privately he abhorred smoking and sympathized with the American Cancer Society’s war against Big Tobacco. The attitude toward smoking was but one of the beliefs in major upheaval during the 1960s and early 1970s. The brutality of the race riots and of the war in Vietnam revealed a national moral emergency, also evident locally in a New York City wracked with crime, strewn with debris, and on the brink of bankruptcy. It was against this background that Penn learned in 1971 that his mentor and father figure, Alexey Brodovitch, who was never without a cigarette, had died of cancer. Less than year later, Penn began a new project: collecting decaying cigarette butts from the city’s streets and carefully recording them in his studio where these shards of civilization from the gutter took on greater resonance. Laying them out to be photographed, Penn saw their uncanny relationships to individuals and, gathered together, to a nation undone by corporate and government irresponsibility. Printed large and in platinum and palladium metals, these fragile remnants of momentary pleasures internalize the miseries of the age and, in Zen-like fashion, reconcile the base and the beautiful. Irving Penn’s interest in the theme led him to photograph other litter he found in the street, such as flattened paper cups or old playing-cards. Through his lens, street litter became something fascinating, almost iconic, however, while simultaneously expressing an explicit consumer criticism through them. Irving Penn composed his still-life photographs like a painter, working with large-format cameras, and was tireless in his attempts to expand the creative possibilities of the medium. He was deeply involved in each stage, from the meticulous composition of the picture to making his own prints. Unlike most other art photographers, he experimented with platinum-palladium and silver gelatin prints in order to lend each of his works a distinctive texture and original character. With his unique signature and stringently reduced aesthetic, he remains a defining stylistic influence, an inspiration to countless successors.

*Big Tobacco is the “big five” largest global tobacco industry companies which are Philip Morris International, British American Tobacco, Imperial Brands, Japan Tobacco International, and China Tobacco.

Info: Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac. Villa Kast, Mirabellplatz 2, Salzburg, Duration: 8/6-16/7/19, Days & Hours: Tue-Fri 10:00-18:00, sat 10:00-14:00, www.ropac.net