ART-TRIBUTE:David Wojnarowicz

Beginning in the late 1970s, David Wojnarowicz created a body of work that spanned photography, painting, music, film, sculpture, writing, and activism. Largely self-taught, he came to prominence in New York in the 1980s, a period marked by creative energy, financial precariousness, and profound cultural changes. Intersecting movements (graffiti, new and no wave music, conceptual photography, performance, and neo-expressionist painting) made New York a laboratory for innovation. Wojnarowicz refused a signature style, adopting a wide variety of techniques with an attitude of radical possibility. Distrustful of inherited structures—a feeling amplified by the resurgence of conservative politics—he varied his repertoire to better infiltrate the prevailing culture.

Beginning in the late 1970s, David Wojnarowicz created a body of work that spanned photography, painting, music, film, sculpture, writing, and activism. Largely self-taught, he came to prominence in New York in the 1980s, a period marked by creative energy, financial precariousness, and profound cultural changes. Intersecting movements (graffiti, new and no wave music, conceptual photography, performance, and neo-expressionist painting) made New York a laboratory for innovation. Wojnarowicz refused a signature style, adopting a wide variety of techniques with an attitude of radical possibility. Distrustful of inherited structures—a feeling amplified by the resurgence of conservative politics—he varied his repertoire to better infiltrate the prevailing culture.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Museo Reina Sofía Archive

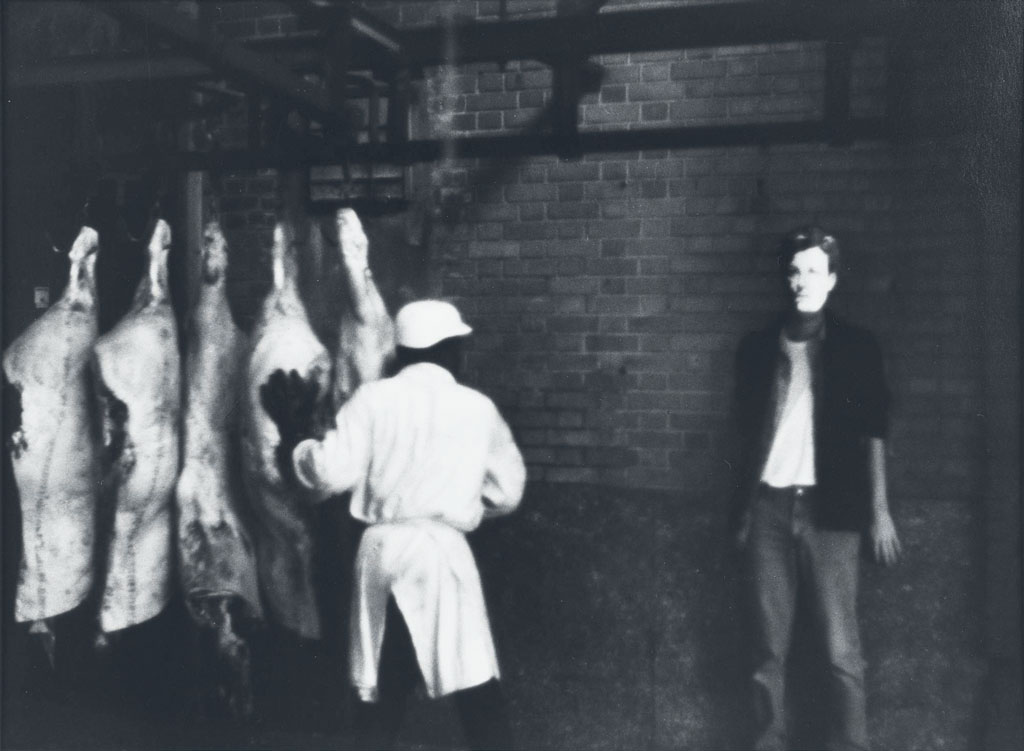

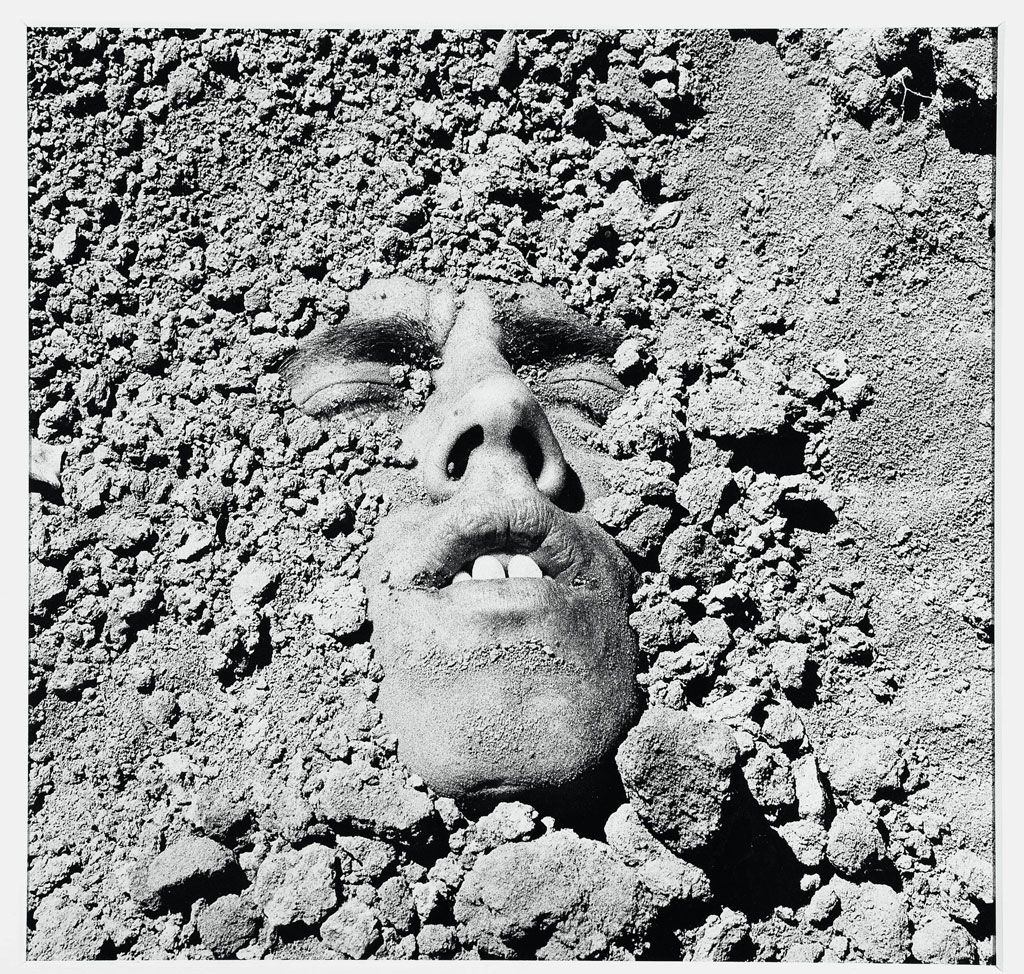

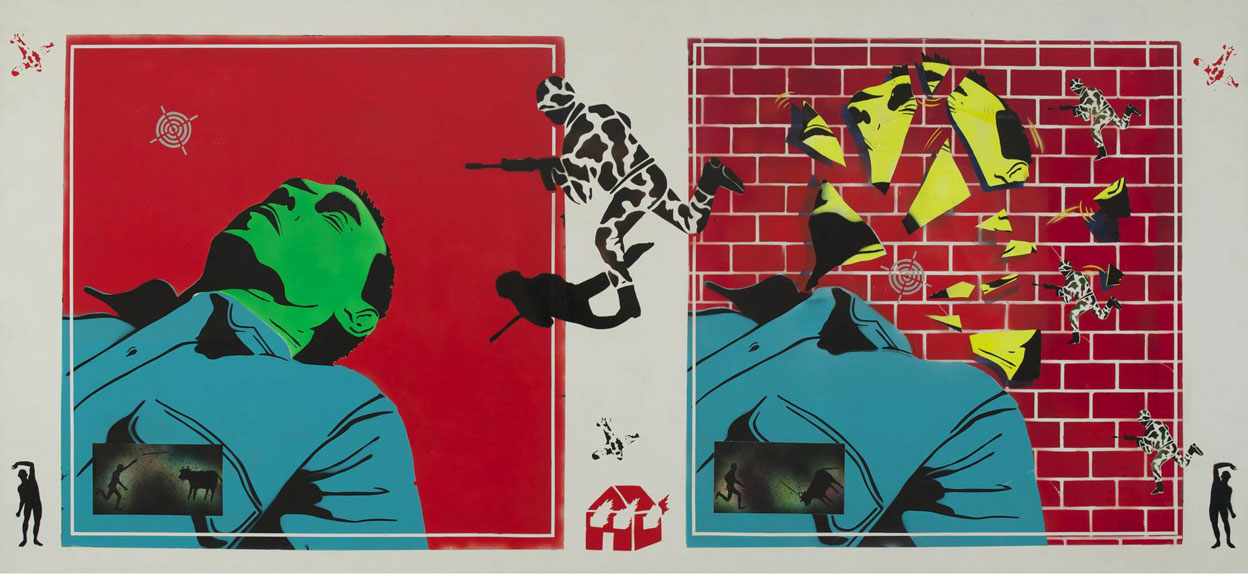

The major retrospective “David Wojnarowicz. History Keeps Me Awake at Night” is the first major review of the multifaceted creative work of the artist, writer and activist David Wojnarowicz and brings together approximately 200 works. This exhibition not only examines the plurality of styles and media that the artist displayed in his practice, but also relates his work to the political, social and artistic context of New York in the 1980s and early 1990s. Before being a visual artist, Wojnarowicz was a poet. In the 1970s, when he wanted to become a writer, he had great admiration for the iconoclastic French poet Arthur Rimbaud and, in a way, their lives resembled each other. With the French poet as a reference, just after returning from a trip to Paris, a 24 year old Wojnarowicz photographed three of his friends strolling through the streets of New York with a life-size Rimbaud mask, the original of which can be seen at the beginning of the exhibition. Next to it there are 39 snapshots of what is now considered a canonical work: the series “Arthur Rimbaud in New York” (1978-79), produced by Wojnarowicz in places that had been important to him. His close relationship with literature also shows the great influence that other writers such as William S. Burroughs and Jean Genet exerted on his work. Both authors appear in two collages: “Untitled (Genet portrayed by Brassaï)” (1979) and “The Recurring Dream of Bill Burroughs” (1978). The early adoption of the seriality of the photographs and the use of collage mark the beginning of Wojnarowicz’s stage of artistic maturity. In the early 1980s, Wojnarowicz had no fixed source of income. That’s why he recycled all kinds of found materials, such as trash can lids or posters and “all for one dollar” stores in the Lower East Side neighborhood. His main work scenario was the abandoned buildings on the Hudson River docks. Wojnarowicz introduced a new dimension to his work with the most important piece he presented in an exhibition that took place in 1984: a series of shelves with 23 heads (in reference to the number of pairs of human DNA chromosomes) of plaster with paint and collage bearing the collective title “Metamorphosis”. These monster/alien/mutant heads had already appeared in some stencils and collages, but this was the first time it had taken on a three-dimensional form. The installation, reminiscent of a firing squad wall, referred to the conflicts then ravaging Central and South America: the Nicaraguan Contra, the civil war in El Salvador or the dirty war in Argentina. The spectre of torture, the disappeared and the violation of human rights was a shadow hanging over the entire American continent. Wojnarowicz met Peter Hujar in 1980. They were lovers for a short time, but their relationship intensified and evolved into a friendship impossible to categorize. As can be seen in the following area of the exhibition, the two friends portrayed each other on several occasions. Twenty years older than Wojnarowicz, Hujar was a photographer and a well-known figure in New York art circles, and his portraits were much appreciated. By the time they met, Wojnarowicz had not yet found his true vocation. It was Hujar who convinced him that he was an artist and encouraged him to paint, something Wojnarowicz had never done before. In 1987, when Hujar died of AIDS, Wojnarowicz would declare that he had been “my brother, my father, my emotional link to the world”. The videos show a selection of excerpts from films shot in the late 1980s. At the end of October 1986, he traveled to Mexico, where he filmed the Day of the Dead festivities and other scenes in Teotihuacan. In these images we can see how the red ants walk along a clock, some bills and a crucifix that Wojnarowicz took with him on his return. The artist, who had been educated in Catholicism, would affirm years later that Jesus Christ “wanted to bear the suffering of all humanity”. When the AIDS crisis intensified, he tried to find a symbolic language that would allow him to synthesize the notions of spirituality, mortality, vulnerability and violence. He began to assemble the images he had shot in Mexico to create a film called “A Fire in My Belly” which he never finished. In the mid-1980s, Wojnarowicz’s paintings took a new direction, and the compositions and themes became more daring and complex. The titles of these paintings and subsequent photographic collages provide clues to his interpretation of the social, economic, and cultural aspects of contemporary North America and its relationship to Western civilization. Wojnarowicz used the term “pre-invented” to designate the prescribed order. In his view, we can only know the world before the appearance of man – the world before the invention of railway tracks and motorways, expanding cities and industrial complexes, maps and coins – by opposition, an antithetical definition of the contemporary world. Various paintings from Wojnarowicz’s exhibition “The Four Elements” are shown. These symbol-laden paintings, of enormous technical complexity, are allegorical representations of earth, water, fire and air. In this case, the artist offers a personal interpretation of a theme with a long tradition in European art. By relating his own epoch to a historical theme, he vindicates the lineage of his work, while affirming the singularity and specific violence of the present. Wojnarowicz was in Peter Hujar’s hospital room when his friend died of AIDS-related complications. As soon as Hujar died, he filmed and photographed his friend for the last time. The three delicate images of Hujar that can be seen, were collected during this last meeting. Although Wojnarowicz continued to draw and paint after Hujar’s death, photography and writing would take on a special prominence until the end of his life. Another room collects some works from the only retrospective that Wojnarowicz inaugurated in life, “David Wojnarowicz: Tongues of Flame”, which was held at Illinois State University in Normal in 1990. In the run-up to this exhibition, the artist began work on four huge paintings of exotic flowers as a symbol of the AIDS crisis and his own illness. Also on presentation are other works that, as with previous pieces in the exhibition, reflect that world maps were another fundamental material for Wojnarowicz, who used them to create pictorial collages such as “Untitled (Peter Hujar dreaming)” (1982). Wojnarowicz’s work deals with the mechanisms, policies and machinations that power uses to give visibility to some lives and deny it to others. The desire to give presence to bodies – the obsession with creating an open space in which to reproduce, through language and images, homosexual representations that are almost never seen – is a restlessness that runs through his entire work and which was exacerbated by the AIDS crisis to give rise to the piece we can see at the end of the exhibition: “Untitled (One Day This Kid…)” (1990-1991) is perhaps Wojnarowicz’s best-known work. The silhouette of a child is Wojnarowicz himself. In the text that surrounds him, the future of this child is described, a future marked by aggressions and homophobia. This piece, like so many others of his, has become a symbol of the spirit of protest, struggle and resistance.

Info: Curators: David Breslin and David Kiehl, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Sabatini Building, Calle de Santa Isabel 52, Madrid, Duration: 29/5-30/9/19, Days & Hours: Mon & Wed-Sat 10:00-21:00, Sun 10:00-19:00, www.museoreinasofia.es