ARCHITECTURE:At Home-Projects For Contemporary Living

Through the analysis of projects by great Italian masters of the 20th Century and by rising stars of the international architecture scene kept in the architecture collections of the MAXXI museum, the exhibition “At Home Projects For Contemporary Living” reveals some of the many answers that architects have given to questions passing from the individual dimension to the collective one.

Through the analysis of projects by great Italian masters of the 20th Century and by rising stars of the international architecture scene kept in the architecture collections of the MAXXI museum, the exhibition “At Home Projects For Contemporary Living” reveals some of the many answers that architects have given to questions passing from the individual dimension to the collective one.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: MAXXI Archive

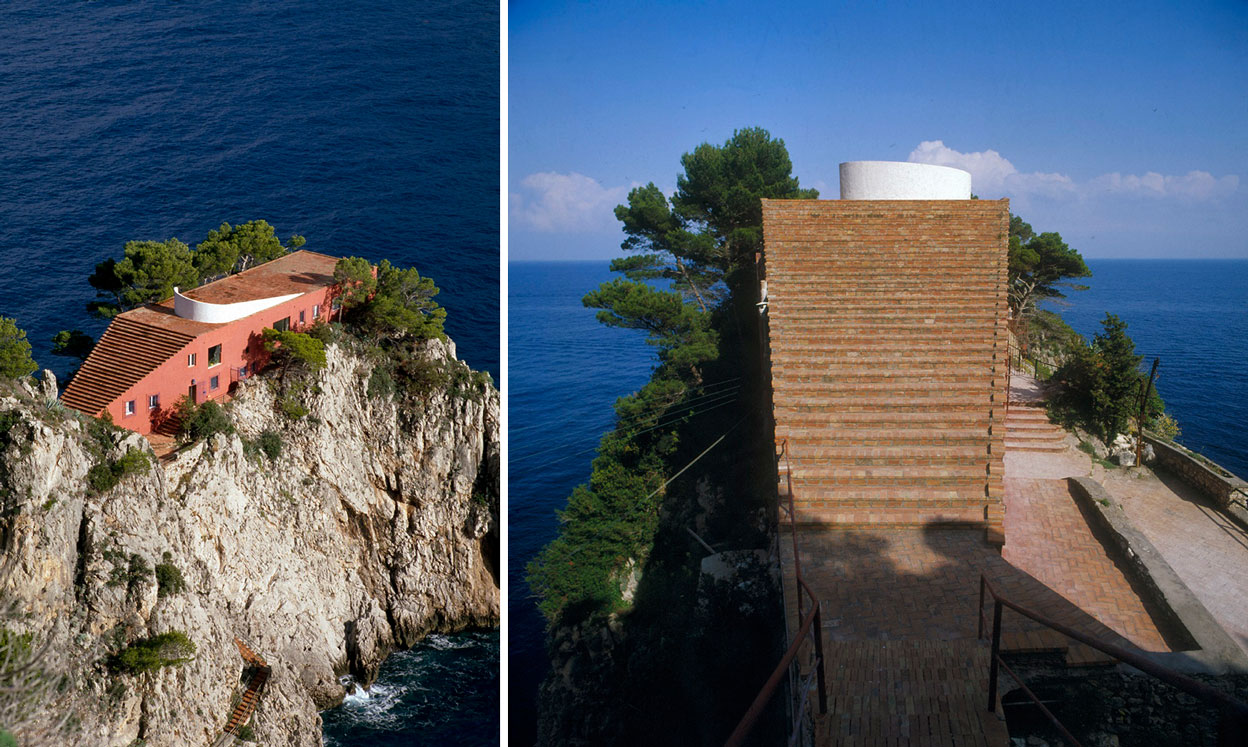

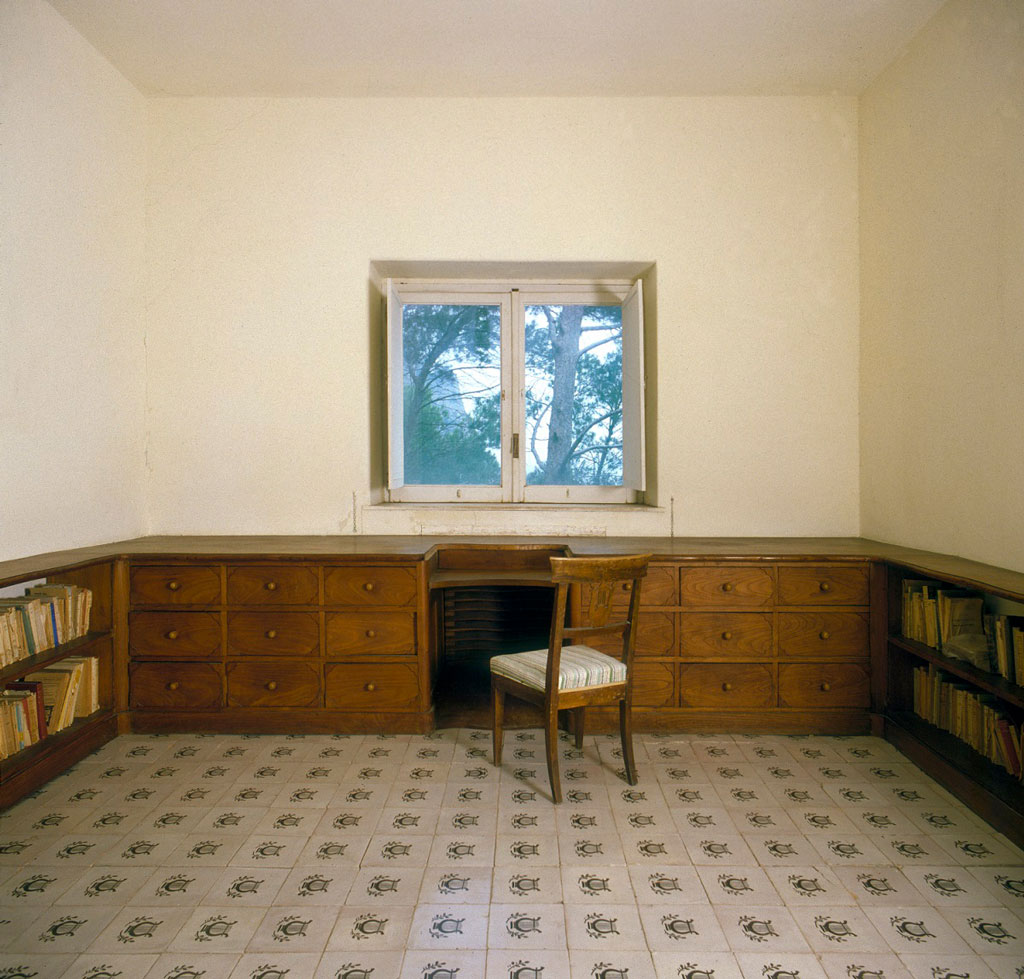

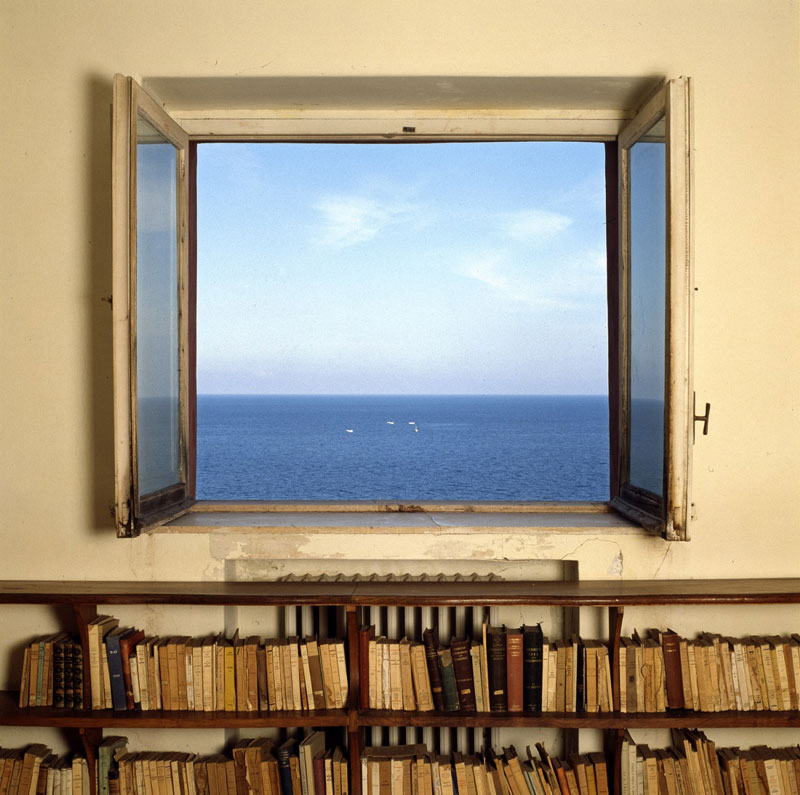

On every scale, housing projects turn out to be an opportunity to think about the forms and materials of architecture, in close connection to nature or inserted in the urban fabric, in response to new identity requests expressed by clients who were well aware of their role or as a result of residential reconstruction plans of the post war period. The central motiv of “At Home. Projects For Contemporary Living” itinerary is the on-going dialogue – based on correspondences to be found – between the work of a master of architecture and an architect of the new generation: projects that are distant in time and space but similar for the methods applied, for the context in which they are built or for the formal research that inspired them. These are placed in a direct visual comparison to inspire further suggestions, but above all to highlight through the presentation of these different and complex projects, the variety and complexity of contemporary living spaces. The exhibition opens with an immersive experience inside a real house built in the Museum gallery based on a project by the Norwegian architects Rintala Eggertsson “Home sweet Rome” is the beginning of an exhibition that, starting from the almost domestic dimension of an insula of ancient memory, then leads to the most modern experiments on individual and collective housing. Apparently blasphemous, the juxtaposition of Villa Malaparte by Adalberto Libera and the new Bivouac Fanton by Demogo is at the same time a dare and an act of faith in Italian architecture. Capable, at the dawn of modernity, of descending like an ark on Capo Massello without losing neither its abstract character nor its vernacular and Mediterranean identity, our architecture is still capable today of landing with grace and radicalism on a mountain top in the Dolomites, maintaining an attitude of both challenge and respect. We reach back to Villa Malaparte to rediscover the sublime originality of the physical and cultural Italian landscape, and we place it next to the Fanton because it also is a high-impact beauty, that seeks no mimesis. The two buildings also record the change in time and cultures. In Capri, the building latches onto the rock with brutal wisdom; on the Marmarole Pass, the object is placed down lightly and with a strange sense of temporariness, that enhances the paradoxical nature of the project. Can Carlo Scarpa come to mind when looking at projects by Maria Giuseppina Grasso Cannizzo? Under many aspects, the two couldn’t be more distant: Veneto against Sicily, infinite detail against austere precision in the approach, poetics of the fragment against a proud sense of formal and expressive unity. However, they also have much in common: the individual nature of their research, a passion for materials and their specific qualities, the many – but not necessarily looked for – occasions to work on a small scale, closeness with art, the ability to “design” their own clients, the distant echo of Japanese accuracy. As some of Scarpa’s creations, the house in Modica is a work of art in its fullest sense, imagined together with its bold construction method and the effect it would have on the landscape and its inhabitants. As always, what strikes us is the amplitude of Grasso Cannizzo’s design language, as technical as an engineer, as synthetic and visionary as an abstract artist. Luigi Pellegrin and Giuseppe Perugini are two heroes of the wildest and most interesting phase of Italian architecture. With constant support by Bruno Zevi, they were both tireless creators of projects directed towards a technical and social future, intolerant towards “paper” utopias. They both had a penchant for the public or even monumental dimension, made up of schools, public buildings, large complexes. It is therefore interesting to see them here self-commissioned and “forced” to a domestic dimension, while they try to empty the architecture of the house of any intimate aspect to transform it into a purely spatial archetype. In his semi-detached family villa, Pellegrin uses the building plan as if it were one of his memorable sections, he makes it burst and imagines it at the centre of an infinitely dynamic perspective spatial system. The Perugini family’s Casa Albero – another “house like me” – is built as an organic structure to which individual cells containing domestic spaces are added, as in a cellular organism with unlimited growth. Roman Baroque is among the architectural passions that Zaha Hadid often mentioned, wit its ability to sculpt the urban space, its unique blend of solidity and lightness. Her project for the MAXXI is perhaps the most explicit testimonial to this passion, which is however also present in her later work and in her firm’s current projects. It in fact appears in the house built near Moscow, in the characteristic way in which the dynamic development of curved shapes is interwoven with the sudden changes in altitude and height. It is unavoidable to travel back in time and place this project designed by Hadid’s office beside the first successful tribute to Baroque tradition, namely Casa Baldi by Paolo Portoghesi, creative in its form and spaces, traditional in materials. The connection between the two architects becomes clearer if we consider the second – unbuilt – project for the same house: slender in height, hyperdynamic, enriched by a complex series of rotations and vertical spatial joints. In his last project in Berlin, on Schützenstrasse, Aldo Rossi translated his love for Berlin and its city blocks into a mature and disenchanted project, where the façades of the block are fragmented into a sequence of small independent fronts. Their dimensions do not correspond to the block’s internal organization, their language tells of different ages and moments, their appearance does not necessarily translate into structural reality. At the end of his career, Rossi finally gives in to irony and hides, among the other fragments of facade, a span taken from Palazzo Farnese’s façade. Less ironic but equally curious about history, Urbanus the Chinese architects of the Vankle Tulou Housing are faced with having to build the city rather than integrate it, and take direct inspiration from the astonishing historical building type from southern China, the hakka houses. These are large circular complexes with a central space occupied by the common spaces and lower constructions, and where the family expands and branches out to become community. The juxtaposition of Giancarlo De Carlo and David Adjaye is motivated by a certain design attitude that the two architects share. For both of them, architecture is the patient research for a balance between a pure passion for form and the needs of those who will inhabit these spaces and give them their final identity. De Carlo builds his Urbino by superimposing the routes and the dynamics of today’s residents – students, architecture tourists, his friend Sichirollo – onto the historic city. With Sugar Hill, Adjaye builds in the heart of New York’s accelerated capitalism a perfect example of post-modern welfare, based not only on the granting of spaces and services, but inserted – similar in this to De Carlo’s Urbino – in a context of culture and education. Both refuse the “dictatorship of the ground line”, they pierce through floors and sections to distribute movement and light. They both have an “enlightened” confidence in the power of architecture and education.

Info: Curators: Margherita Guccione and Pippo Ciorra, MAXXI-Museo nazionale delle arti del XXI secolo, Via Guido Reni 4A, Rome, Duration: 17/4/19-30/4/20, Days & Hours: Tue-Fri & sun 11:00-19:00, Sat 11:00-22:00, www.maxxi.art