ART CITIES:Madrid-Tetsuya Ishida

Tetsuya Ishida came of age as a painter during Japan’s “lost decade”, a time of nationwide economic recession that lasted through the 1990s. In his afflictive paintings, he captured the feelings of hopelessness, claustrophobia, and emotional isolation that burdened him and dominated Japanese society. From his early career until his untimely death in 2005, Ishida provided vivid allegories of the challenges to Japanese life and morale in paintings and graphic works charged with dark Orwellian absurdity.

Tetsuya Ishida came of age as a painter during Japan’s “lost decade”, a time of nationwide economic recession that lasted through the 1990s. In his afflictive paintings, he captured the feelings of hopelessness, claustrophobia, and emotional isolation that burdened him and dominated Japanese society. From his early career until his untimely death in 2005, Ishida provided vivid allegories of the challenges to Japanese life and morale in paintings and graphic works charged with dark Orwellian absurdity.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía Archive

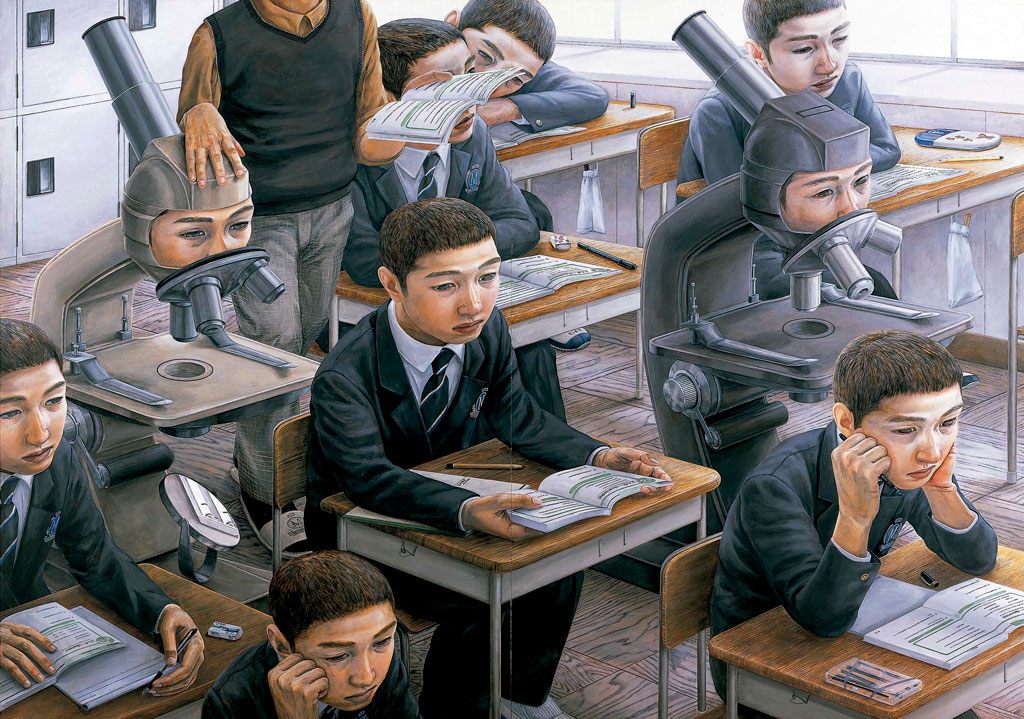

“Self-Portrait of Other” is the title of the first retrospective exhibition of the work of Tetsuya Ishida to be held out of Japan. It brings together a significant selection of around 70 paintings and drawings, from 1996, the year he finished his degree in fine art at Musashino University, Tokyo, to 2004, shortly before his sudden death. His paintings, drawings, and notebooks are a testimony to the malaise and alienation of contemporary subjects in advanced capitalism. A cult artist in his own country, where his imaginary world has become a reference for younger generations, his sharply critical work was presented in Europe at the 56 Venice Biennale in 2015. Ishida’s skeptical, nihilistic realism bears witness to today’s normalization of precarity and consumption in every sphere of life. The characters in his works are hybrid, anthropomorphic machines who embody a state of total technological domination and limitless subordination to a new, inescapable form of slavery that makes no distinction between work and consumption and heightens the anxiety of our bodies and subjectivities. Ishida’s bitter social satire cuts away at the Japanese postwar financial miracle, stripping it of any idealistic consideration. Although the 1973 petrol crisis briefly affected scientific, industrial, and technological growth in Japan, the country’s developmental trend was boosted in the 1980s at the height of real estate speculation, which led to the bursting in 1991 of the financial bubble and the deep depression that followed. This was a gloomy period of wholesale economic restructuring fed by the need to adapt and reinvent: factories intensified large-scale robotic automation, industrial methods were used to rationalize the workforce, the service sector took over from manufacturing, and unemployment rates rose to previously unseen levels. Ishida was one of the so-called lost generation of those years, the skeptical product of truncated lives and unmet expectations that resulted from the crisis. Works dated 1996, such as “Derelict Building Department Head’s Chair”, “Under the Company President’s Umbrella”, “Refuel Meal” and “Conveyor Belt People”, are lucid, uneasy reflections on the transformations in the Fordist production line within the financial and service economy’s mass factory of social mutilation. At the same time, the period’s accelerating, unstoppable development of new forms of consumption was leading to new forms of attachment and community life (as “Convenience Store Mother and Child” (1996), as well as isolation in both public and domestic spaces. After 1995, when the use of personal computers was democratized in Japan, the increasing tendency in youth toward introspection often led to the dramatic, voluntary reclusion of the hikikomori, youth who withdraw into virtual worlds and choose a lifestyle of marginal vegetation, as suggested by the works “Sleeping Pill Bug” (1995) and “Hothouse” (2003). Ishida’s work pinpoints the obsessions of the individual who oppressively inhabits undistinguishable spaces and times where work, consumption, and free time merge. Kafkaesque references appear in the larval states of the imprisoned, tamed subject in “Sleeping Bagworm” (1995) or the social coercion of real powers like the educational system is works like “Awakening” (1998) and “Prisoner” (1999); the means by which the mass media penetrate our lives in “Untitled” (1995); and the business culture of the “salaryman,” the archetypal worker who gives his entire life to his company in “Toyota Ipsum” (1996). Ishida’s alienated vision of contemporary society is personified in this automated figure, who has lost all connection to the products of his labor and is alienated from the labor process itself through its conversion by the post-Fordist economic paradigm into miscellaneous services where goods are rationalized, labeled, and distributed. Ishida dresses his armies of students and clone-like workers to signify their uniformity, which is also expressed in their identical, expressionless, unmistakable features. These are duplicated from one painting to the next like a mirror image of one individual representing the many. This anonymous figure has been seen as a self-portrait of the artist. Although Ishida denied this identification in many interviews and writings, he did acknowledge his empathy toward the pain, pessimism, and anonymity of today’s city dwellers, particularly those in megalopolises like Tokyo. Ishida plays with the scales between things, buildings, and people and dislocates spatial relationships in his compositions, accentuating the viewer’s disquiet at the lack of emotion and other signifiers of communal memory in his work. His body-machines, objectified and bound, exist in solitary confrontation with the disorientation of depersonalized urban spaces, or question their adolescent identities or childhood, which opens up as a sort of black hole into a disturbing regression that still carries some innocence.

Info: Curator: Teresa Velázquez, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Palacio de Velázquez, Parque del Retiro, Paseo Venezuela 2, Madrid, Duration: 11/4-8/9/18, Days & Hours: Daily 10:00-22:00, www.museoreinasofia.es