ART-PRESENTATION: Roberto Matta and the Fourth Dimension

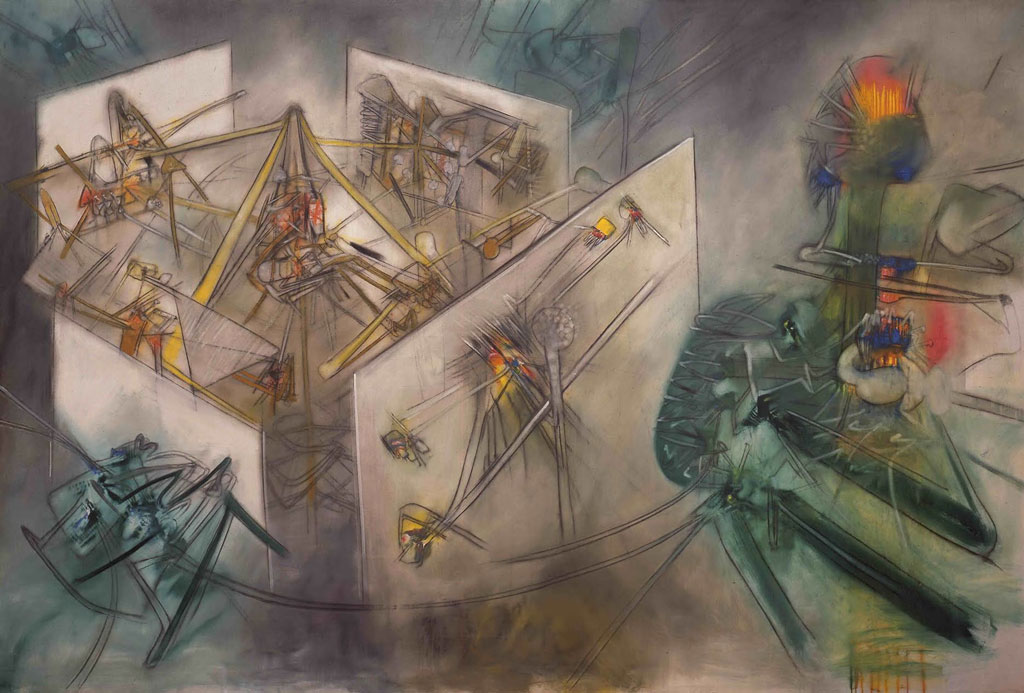

Roberto Matta, in full Roberto Antonio Sebastian Matta Echaurren was an international figure whose worldview represented a synthesis of European, American, and Latin American cultures. As a member of the Surrealist Movement and an early mentor to several Abstract Expressionists, Matta broke with both groups to pursue a highly personal artistic vision. His mature work blended abstraction, figuration, and multi-dimensional spaces into complex, cosmic landscapes.

Roberto Matta, in full Roberto Antonio Sebastian Matta Echaurren was an international figure whose worldview represented a synthesis of European, American, and Latin American cultures. As a member of the Surrealist Movement and an early mentor to several Abstract Expressionists, Matta broke with both groups to pursue a highly personal artistic vision. His mature work blended abstraction, figuration, and multi-dimensional spaces into complex, cosmic landscapes.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: The State Hermitage Museum Archive

For the first time in Russia is on show an exhibition with works by Roberto Matta, τhe exhibition “Roberto Matta and the Fourth Dimension” features over 90 works from 23 Private Collections, mostly from the USA, showing Matta’s unique understanding of space and the evolution of the artist, who was able to find his own vison of the world through the fourth dimension and project it on canvas. Born in Santiago, Chile on 11/11/1911, Roberto Matta trained as an architect and interior designερ at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Matta moved to Paris and worked as a draughtsman for Le Corbusier from 1934 until 1937. Matta developed friendships with important artists and patrons including Gertrude Stein, Marcel Duchamp, Salvador Dalí, and Andre Breton while living in Europe in the 1930s. Eventually, Breton invited Matta to join his circle of Surrealist artists. Affected by the ideas of non-Euclidian geometry, Matta tried to give shape to the structures built in his mind, to create space beyond the visible, conventional perspective. After taking part in the International Surrealist Exhibition of 1938, largely thanks to his friendship with the English painter Gordon Onslow Ford, Matta started researching what he called “psychological morphologies”. Ford introduced him to the works of Peter D. Ouspensky, a Russian philosopher and a theorist of the “fourth dimension.” Matta shared Ouspensky’s idea that the fourth dimension adds to the third dimension the feeling of space, of motion, and of time that is essential for one to realize the constant and irreversible process of change in the world, where every new moment is different from the previous one. Ouspensky wrote in his book “Tertium Organum” (1912) that the human mind subconsciously “corrects” what the eye sees, in order to make up for the limitations of human vision. For example, mental concepts help us perceive volumes, though we only can see the outward surfaces of objects. According to Ouspensky, it is the artist who takes on the special role of guide and visionary, who “has to see what others cannot see” and “has to have the gift to open the others’ eyes to what they cannot see themselves”. In order to clarify his point, Ouspensky would often draw geometric lines, planes, cubes, and spheres as metaphorical explanations for the human psyche. Matta took the latter’s usage of geometry to describe unseen structures. Overcoming the limitations of human vision, he strived to create art that “can see more and further”. Like many artists, Matta fled Europe for the United States in 1938 to avoid World War II. Around the same time, he moved away from his background in architectural drawing and transitioned to painting. Roberto Matta’s first one-man exhibition was at Julien Levy Gallery in New York City in 1940. Throughout the following decade, Matta was deeply interested in psychoanalysis, resulting in “inscapes” or paintings that explore the subconscious. During the 1940s, Matta focused on the Surrealist notion of automatic response, or illustrating the unconscious beyond the rules of rational society. This involved explorations of dreams, time, and space. “When you look at his work it’s evident he uses glass walls that are the separation point between conscious and unconscious, or those thoughts that we keep inside and those we let the world see”. While living in New York, Matta became intertwined with the New York School of painting and the Abstract Expressionist Movement. At the time, artists like Robert Motherwell, Jackson Pollock, and Arshile Gorky were deeply interested in the ideas emerging from the Surrealists in Europe. Because he was a multicultural person and spoke five or six languages, he brought those theories to the United States and was able to explain and discuss them with the early New York School artists. Motherwell, who spent the summer of 1941 learning from Matta, described him as “the most energetic, enthusiastic, poetic charming, brilliant young artist that [he’d ] ever met…he gave me a 10-year education in Surrealism”. When Matta went back to Europe in 1948, he broke with the Surrealists and moved toward a style all his own. During the 1940s, Matta relayed the concepts of Surrealism to early New York School artists and Abstract Expressionists. Though he eventually moved past these movements in favor of a more nuanced exploration of socio-political issues. Many of Matta’s works also included biomorphic elements, which are abstracted forms that reference plants and human bodies. Other themes that present themselves in Matta’s work include Greek mythology and the cosmos. In the 1950s and 1960s, Matta refocused on more overtly political themes and began to incorporate figures into his paintings. Upset with the status quo, Matta drew on events like the Rosenberg trial of 1954 for inspiration because he believed that artists had a responsibility to comment on the human condition. From the 1960’s through the 1990’s Matta’s paintings danced into hyperspace, delved into cosmic landscapes and brought attention to both the earth and the inner worlds as a dynamic and vibrant place of pregnant potential. Over the years, Matta kept close contact with astrophysicists. The recent scientific discovery of “antimatter” which indicated a major portion of the universe was invisible, excited him as it confirmed his sixty-year quest of catching what cannot be seen by the naked eye. Referring to scientists, Matta commented: “they don’t have any visual language. It has to come from the artist. That is the role of art … they really need an artist to show images which are not anthropomorphic images of the Greek gods, animals, and birds, but some constellation of matter which tends to become life”.

Info: Curators: Dmitry Ozerkov and Oksana Salamatina, White Hall of the General Staff Building, The State Hermitage Museum, 2 Dvortsovaya Square, St. Petersburg, Duration: 10/4-30/6/19, Days & Hours, Tue, Thu & Sat-Sun 10:30-18:00, Wed & Fri 10:30-21:00, www.hermitagemuseum.org