ART-PRESENTATION: Nancy Spero-Paper Mirror

Nancy Spero produced a radical body of work that confronted oppression and inequality while challenging the aesthetic orthodoxies of contemporary art. Among the first feminist artists, Spero drew on archetypal representations of women from diverse cultures and times in an attempt to reframe history itself from a perspective that she termed “woman as protagonist”.

Nancy Spero produced a radical body of work that confronted oppression and inequality while challenging the aesthetic orthodoxies of contemporary art. Among the first feminist artists, Spero drew on archetypal representations of women from diverse cultures and times in an attempt to reframe history itself from a perspective that she termed “woman as protagonist”.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: MoMA Archive

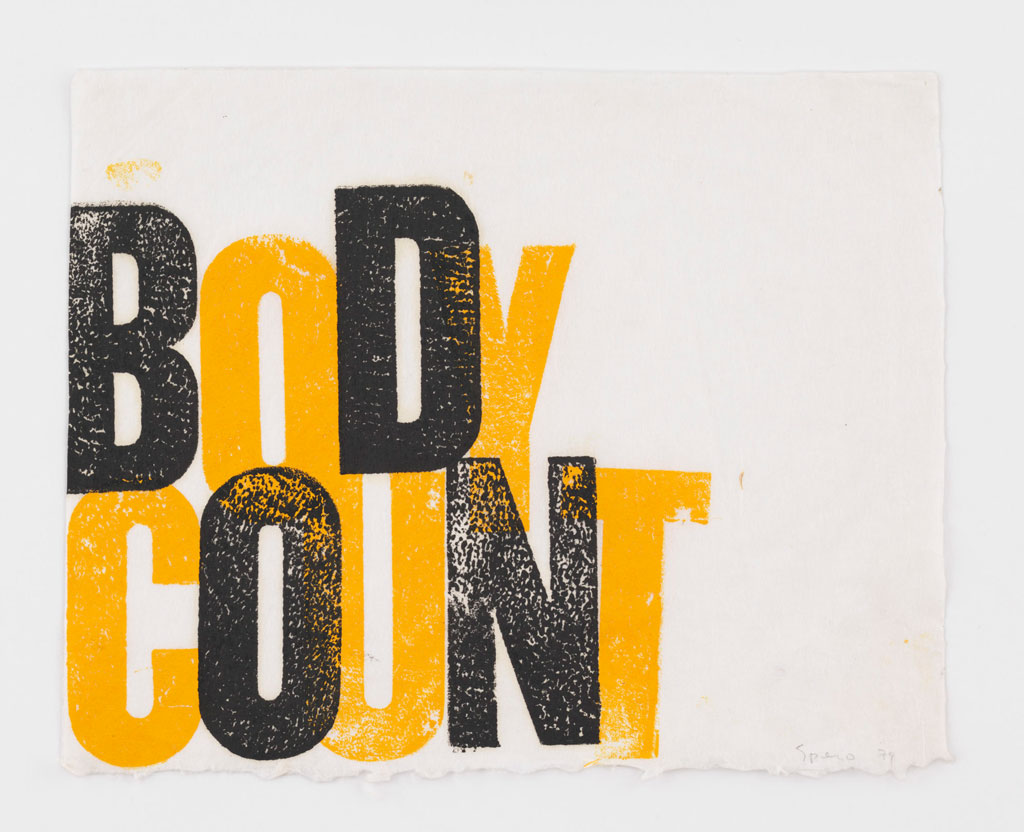

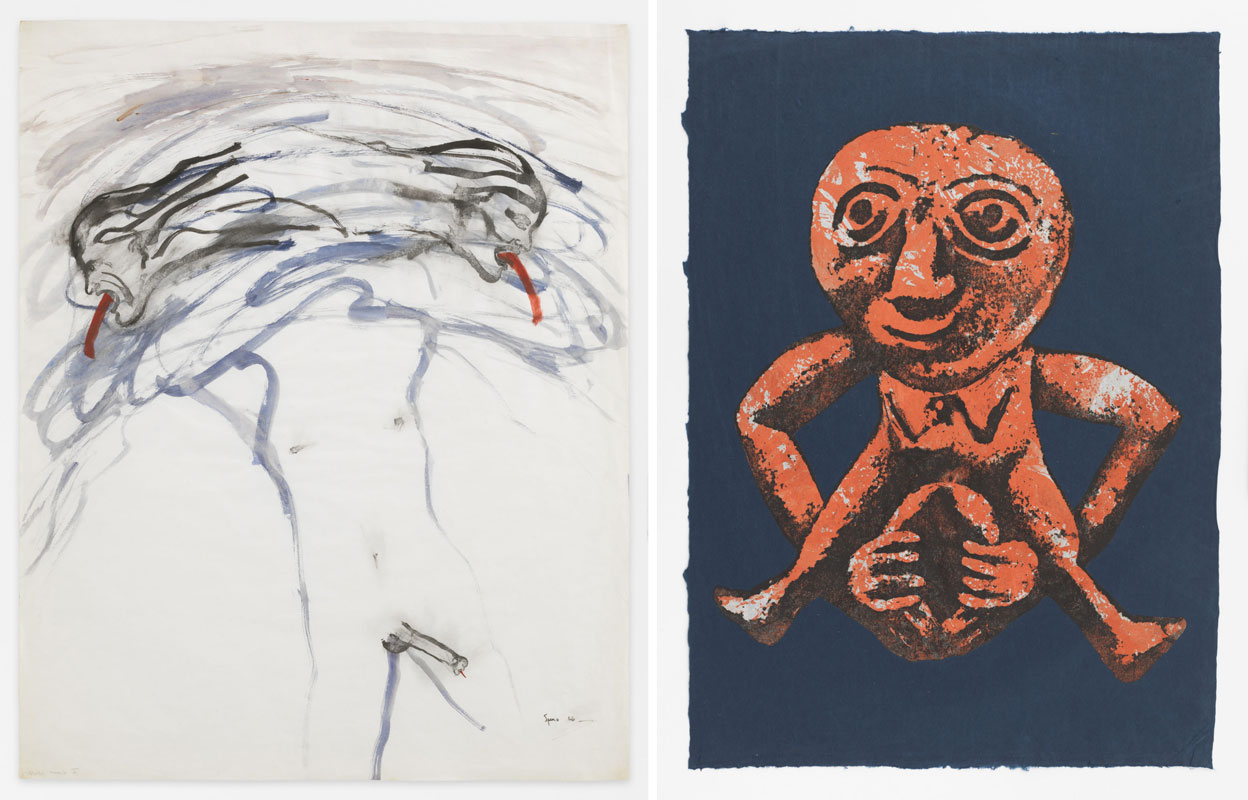

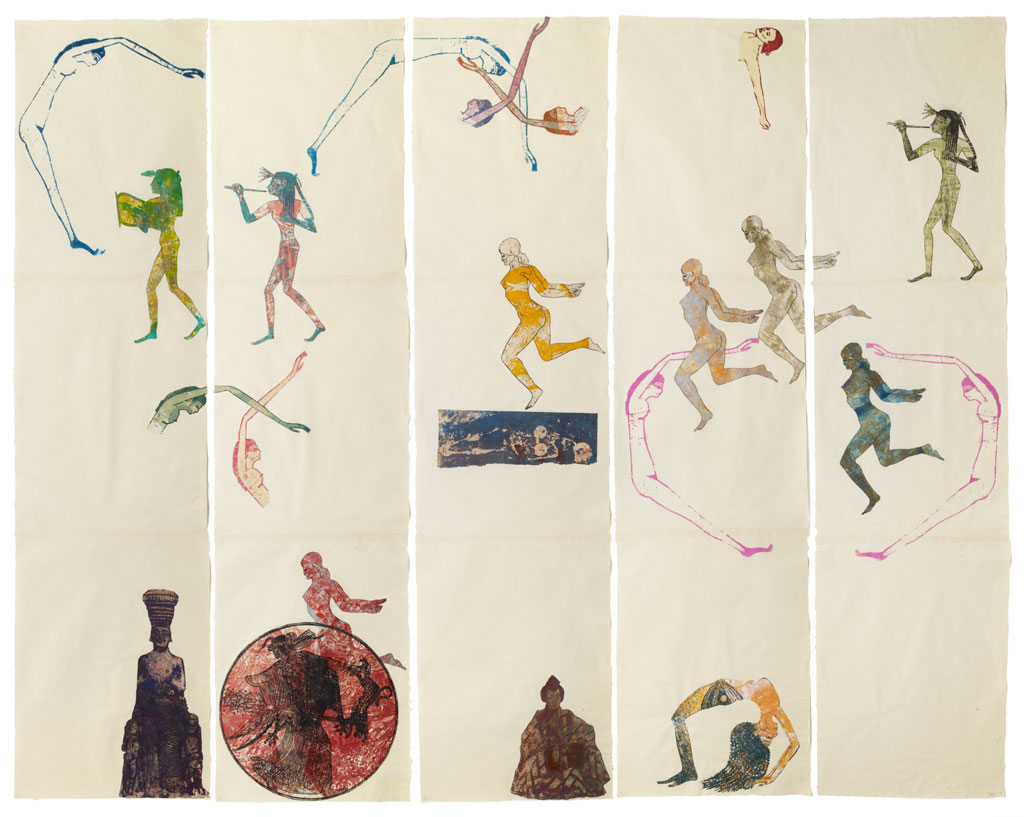

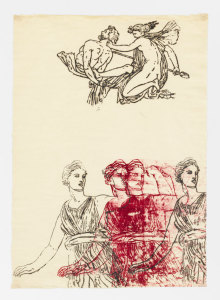

The exhibition “Paper Mirror” surveys the full scope of Nancy Spero’s career bringing together more than 100 works made by Nancy Spero over six decades in the first major Museum exhibition in the U.S.A. since the artist’s death in 18/10/2009. The exhibition features numerous works from the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, including the monumental work “Notes in Time on Women” (1979-81), also featured is the large-scale installation “Maypole: Take No Prisoners” (2007), the last major work the artist completed before her death, originally realized for the Venice Biennale, the work consists of a twenty-foot vertical steel pole with over 200 images of decapitated heads that hang from ribbons and metal chains. Created during the Iraq War but derived from Spero’s earlier drawings that responded to the Vietnam War, Maypole provokes inquiry into the cyclical nature of history, war, and its victims. In 1966, Nancy Spero concluded that the language of painting was “too conventional, too establishment” and decided that from then on she would work exclusively on paper, vulnerable, insignificant paper meant to be pinned to the wall. Having recently returned to the United States after a number of years in Europe, Spero was deeply disturbed by the atrocities the US military was committing in Vietnam, and over the next four years, she created her first significant works on paper, the scores of gouache-and-ink pictures that make up her War Series. As she later described them, these works express “the obscenity of war” via imagery of “angry screaming heads in clouds of bombs that spew and vomit poison onto the victims below. Phallic tongues emerge from human heads at the tips of the penile extensions of the bomb or helicopter blades. Making these extreme images, I worried that my children might be embarrassed with the content of my art . . .”. For Spero, who died in 2009 at the age of 83, choices of material, form, method, and subject matter were always political. Born in Cleveland, Ohio in 1926, Spero graduated from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1949. Before settling with their three sons in New York in 1964, she and her husband, the painter Leon Golub (1922–2004), lived in Paris, where she created her first mature works, the Black Paintings, 1959–1965: figurative compositions that seem to brood over existential questions of selfhood and otherness, several depicting sexual partners who appear remote and estranged from each other. She received little recognition for these powerful paintings. Throughout the 1950s and ’60s, Spero experienced intense isolation, discontent, and anger because of the invisibility accorded a female artist making figurative, aggressive work. Moreover, the lion’s share of child-rearing duties fell to her, leaving little time for artmaking. But Spero was resolute: “I never stopped working and always late at night, proving if only to myself that I was an artist,” she wrote years later. Her fury over being persona non grata in the art world mounted. She had no audience to speak of beyond Golub; no opportunity to exhibit her work except at “a few anti-war shows and benefits”. Feeling like an outsider, in 1969 Spero discovered Artaud’s writings and immediately began to incorporate it into her practice, transcribing his texts into notebooks so that his words would pass bodily through her. The first fully-realized works that emerged from these explorations were the “Artaud Paintings” (1969–70), which juxtapose text fragments redolent of the writer’s “desperation, humor, misogyny, and violent language” with painted images of androgynous figures, disembodied heads, and phallic tongues. Upon completing the “Artaud Paintings”, Spero made an even more decisive break with painterly convention: Having already abandoned the canvas support, she exploded the spatial parameters that governed portraits, landscapes, and modernist abstraction alike. She gathered a mixture of papers from around her studio and glued them into a scroll-like formation, which evolved into “Codex Artaud” (1971-72). An immense series “Codex Artaud” spanned 34 paper panels 51 cm by up to 3-meter long (and tall) that combined typewritten snippets of Artaud’s writing with collaged and painted images: severed heads with extended tongues; snakes with human visages; strange animal forms and human fragments. Beyond the studio, Spero was fighting alienation in other ways. In search of community and collective political agency, in 1969, she joined Women Artists in Revolution (WAR) that fought for women’s rights in the art world. Soon she was active in the Ad Hoc Women Artists’ Committee, which for months picketed the Whitney Museum, protesting the extreme gender disparity in its exhibitions and collections, and which started the Women’s Art Registry to disseminate information about art made by women. A paradigm shift was under way. In 1972 six women, including Spero, founded the first independent women’s art venue in the U.S.A., A.I.R. Gallery. A.I.R. transformed Spero’s social landscape: In addition to having a place in which to exhibit her work consistently, she became an active participant in the discourse of art, and she found the dialogue and constituency she so desperately needed. Spero exhibited “Codex Artaud” at A.I.R. in 1973, her first New York gallery show and mounted five solo exhibitions there over the following decade. Spero experimented with letterpress in a sequence of graphically bold works using war slogans, medieval terminology, and vernacular language “body count”, “explicit explanation”, “search and destroy” or “normal love”. Her “Licit Exp” and “Hours of the Night” series collage sexually explicit figures and poetic fragments. She assembled her first sequence of tall vertical panels into a large-scale hanging, “The Hours of the Night” (1974). Spero’s decision, made in 1974, that women would be the subject of all her future works was a natural outgrowth of her feminist activities. “I decided to view women and men by representing women, not just to reverse history, but to see what it means to view the world through the depiction of women”. She immersed into research into mythologies and histories of the torture and subjugation of women, resulting in scroll environments, including the 38-meter “Torture of Women” (1974-76), drawn heavily from Amnesty International Reports of eye-witness accounts of state-sanctioned torture, and the 60-meter, text-heavy, collaged compendium of references to woman as protag-onist made over a three-year period, Notes in Time on Women, 1979. In 1975, a chance remark by the proprietor of a print shop inspired Spero to begin transferring her painted figures to zinc plates that permitted her to reproduce, repeat, and recycle images freely and infinitely. In the ensuing years she frequently spoke of “cannibalizing” her work, a methodological byproduct of the printing technique she adopted. Through the ’70s and early ’80s, Spero exhibited her work not only at A.I.R. but at other nonprofit spaces, women’s spaces, and university galleries. Then, in the mid-1980s, in the context of pluralism and attention to politicized practices, her work garnered acknowledgment from more prominent institutions and galleries. In 1987, traveling retrospectives originated at London’s ICA and the Everson Museum in Syracuse, New York. Shortly after that, Spero began using cast rubber for printing directly on walls, creating site-specific installations for a variety of museums and art institutions. As her methods evolved, so did her subject matter: Far from lingering in a state of victimage, much of her work of the ’80s and ’90s expresses exuberance and sexual audacity and the delight of movement and liberation. Female figures walk, crawl, dance, run and jump across her compositional space. Although Spero continued to challenge sadism towards women and the brutality of war her whole life, explicit depictions of violence are rare in her later work, which progressively portrayed women as liberated agents of their own narratives. Spero’s installation “Maypole: Take No Prisoners” created for the 2007 Venice Biennale, fuses the “festive and the frightening”. Severed heads handprinted on aluminum are attached to satin ribbons and chains that hang from a tall pole. The heads are cannibalized from the “War” Series painting, “Kill Commies/Maypole” (1967), which features an American flag atop a pole from which heads dangle. Speaking about the Venice installation. The political commitments that animated her work throughout her career are overtly reflected in her content and choice of subject, of course, but they are also subtly embedded in the sequence of production shifts she instigated, which coalesced into a cogent politics of form integral to the indelible work she created. Spero’s six decades of extraordinary art chart her complex path to emancipation via existential inquiry, formal innovation, communal conviction, and aesthetic ecstasy.

Info: Curator: Julie Ault, MoMA PS1, 22-25 Jackson Avenue, Long Island City, New York, Duration 31/3-23/6/2019, Days & Hours: Mon & Thu-Sun 12:00-18:00, www.moma.org