PHOTO:Reenactment in Contemporary Photography

From reenactments of battles to dramatic theater productions, the restaging of historical events has a long history. For some contemporary photographers, reimaging events for the camera has become a powerful means to explore art historical narratives or reinterpret personal stories. The exhibition “Encore: Reenactment in Contemporary Photography” features seven photographers who employ reenactment as a tool to investigate the past.

From reenactments of battles to dramatic theater productions, the restaging of historical events has a long history. For some contemporary photographers, reimaging events for the camera has become a powerful means to explore art historical narratives or reinterpret personal stories. The exhibition “Encore: Reenactment in Contemporary Photography” features seven photographers who employ reenactment as a tool to investigate the past.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: J. Paul Getty Museum Archive

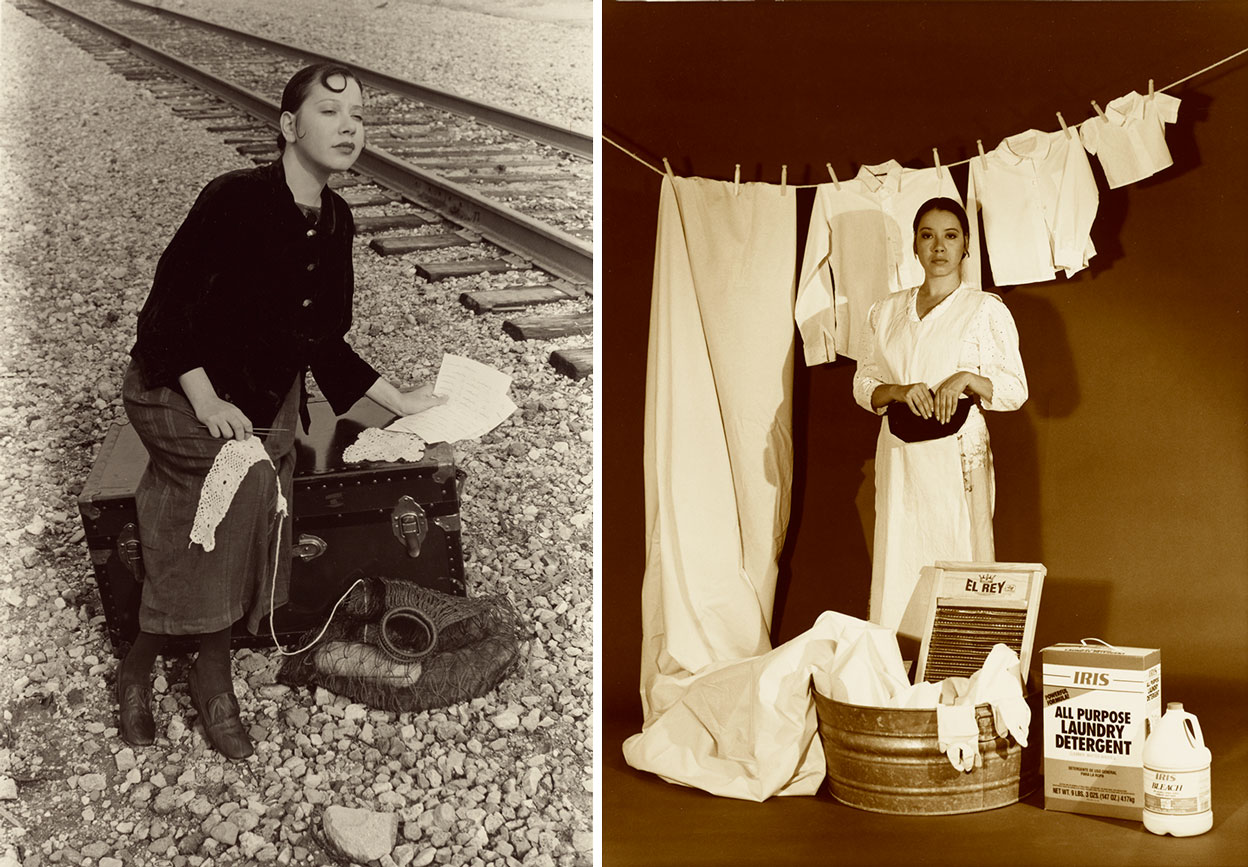

The fascinating and sometimes startling photographs in the exhibition “Encore-Reenactment in Contemporary Photography” weave together allusions to historical events and personalities, famous works of art, and personal narratives as a way to reflect upon the issues of our times, On Presentation at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Center are works by: Eileen Cowin, Christina Fernandez, Samuel Fosso , Yasumasa Morimura, Yinka Shonibare CBE, Gillian Wearing and Qiu Zhijie. These artists explore a range of topics, including the enduring power of celebrated works of art, the legacies of famous historical figures, and the politics of identity. Also, the exhibition includes objects from the Getty Museum’s Permanent Collection and loans from several lenders. Eileen Cowin’s work focuses on the depiction of personal relationships and the exploration of photography’s narrative possibilities. In the mid-1980s, she created a series of photographs in which Cowin, her husband, and her father enact various scenarios inspired by European masterpieces. Eschewing elaborate sets and period costumes, she relies on subtle expressions, dramatic gestures, and familiar poses to allude to her sources. Cast against a black background, the actors wear contemporary clothing, bringing specific art historical moments into the present. By inserting members of her family into well-known images, the artist blurs the line between reinterpreting works understood as masterpieces and alluding to the complexities of familial relationships. Christina Fernandez’s series “María’s Great Expedition” (1995–96) interweaves familial and national histories to create a suite of prints that are both personal and political. Christina Fernandez inserts herself into the title role, and through six photographs of staged scenes and a map reimagines the story of her great-grandmother, who as a single mother migrated from Mexico to Southern California. Drawn from interviews she conducted with family members as well as historical accounts of life in both Mexico and the United States at the turn of the 20th Century, these scenes reference stories about the formidable challenges of starting anew in an unfamiliar place. By employing various costumes and printing techniques, Fernandez signals the passage of time. She also provides intimate narratives that offer insight into the circumstances of María’s journey and undermine stereotypes about immigrants. Samuel Fosso’s series “African Spirits” (2008) presents a series of self-portraits that celebrate prominent political and intellectual figures from countries within Africa and its large and diverse diaspora. These photographs pay homage to individuals who not only championed independence movements and resisted colonial narratives of subjugation but also raised their voices in the American struggle for civil rights. Through meticulous attention to makeup, costume, and pose, the artist restages the physical characteristics of his subjects and re-creates iconic images that originally circulated in newspapers and popular magazines. Among his subjects are the political leader Patrice Lumumba, who was instrumental in establishing the Republic of the Congo; and Aimé Césaire, the French poet and politician from the Caribbean island of Martinique who advocated the celebration of racial identity by black writers. American subjects include civil rights pioneer Martin Luther King Jr., educator and activist Angela Davis, and boxer Muhammad Ali. Since the early 1980s, Yasumasa Morimura has been appropriating and restaging famous works of art, casting himself in the role of the figures depicted. By fabricating elaborate sets and costumes, he does not merely replicate his sources but presents a pastiche of references that simultaneously pay homage to and satirize the original works. His re- interpretations challenge assumptions underlying narratives of celebrated historical episodes while also commenting on Japan’s absorption of Western culture after World War II. Morimura often poses as female characters, further highlighting his otherness in the context of European masterpieces, including poses drawn from paintings by Francisco de Goya and a recreation of Édouard Manet’s Bar at the Folies-Bergère. Some of these constructions also reference the Japanese tradition of Kabuki, highly stylized theatrical performances that include actors with elaborate white mask-like makeup. Yinka Shonibare CBE (Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire) has long explored ideas of contemporary African identity and the legacies of European colonialism and global conquest. For his 2008 series “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters”, Shonibare reworked an iconic etching by the Spanish artist Francisco de Goya in five iterations, each representing a different continent. In each image, the artist depicts a central, sleeping figure whose clothing and appearance are entirely at odds with the continent he represents, including America, Europe and Asia, reflecting the artist’s interest in the complications of race, class, and the construction of cultural identity. For these reenactments Shonibare uses Dutch wax fabrics based on Indonesian patterns, which were produced in Europe for the West African market during the 19th and early 20th Centuries. The 1997 Turner Prize winner Gillian Wearing CBE questions the differences between individual and collective identities through staged photographs, videos, and performances. For her ongoing series “Album” (2003- ), Wearing orchestrates a series of self-portraits using masks, wigs, and prosthetic elements to re-create photographs of her immediate family. Using family photo albums as a source, the artist explores the notion of identity, both in terms of likeness attributable to shared genetic makeup and as shaped by external influences. Highly detailed silicone masks, made with the help of experts from the wax museum Madame Tussaud’s in London, complicate our ability to discern fiction and reality. In these portraits, Wearing explores the way that ordinary people fashion public and private identities, as preserved both in spontaneous snapshots and formal portraits. Known primarily for creating elaborate installations and videos, Qiu Zhijie has also been making staged photographs since the early 1990s. For the series “Standard Pose” (1996), he costumed actors in business attire and directed them to mimic the poses of groups of figures portrayed in advertising posters that appeared after the Cultural Revolution in China. The posters promoted operas meant to instruct people how to be model citizens, featuring slogans such as “Learn from the workers” and “Long live the dictatorship of the proletariat”. The artist’s use of Mao-era propaganda as a source for photographs provides a subtle critique of the party’s growing acceptance of Western worldviews despite its allegiance to a political system rooted in communism.

Info: Curator: Arpad Kovacs, J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Center, 1200 Getty Center Dr, Los Angeles, Duration: 12/3-9/6/19, Days & Hours: Tue-Fri & Sun 10:00-17:30, Sat 10:00-21:00, www.getty.edu