PHOTO:Luigi Ghirri-The Map and the Territory, Part II

Less known than William Eggleston or Stephen Shore, the Italian photographer Luigi Ghirri has worked, at the same time as they, to translate the contemporary world in color. But, unlike those American colourists of the 1970s, he had chosen soft, cold, ambiguous shades. Luigi Ghirri gained a reaching reputation as a pioneer and master of contemporary photography, with particular reference to its relationship between fiction and reality (Part I).

Less known than William Eggleston or Stephen Shore, the Italian photographer Luigi Ghirri has worked, at the same time as they, to translate the contemporary world in color. But, unlike those American colourists of the 1970s, he had chosen soft, cold, ambiguous shades. Luigi Ghirri gained a reaching reputation as a pioneer and master of contemporary photography, with particular reference to its relationship between fiction and reality (Part I).

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Jeu de Paume Archive

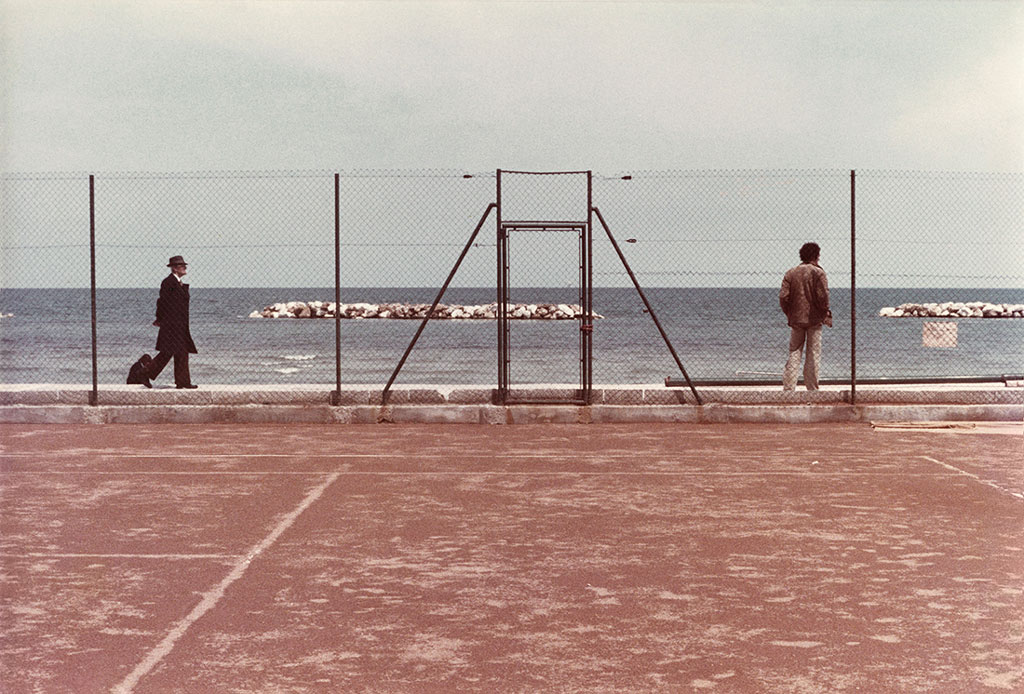

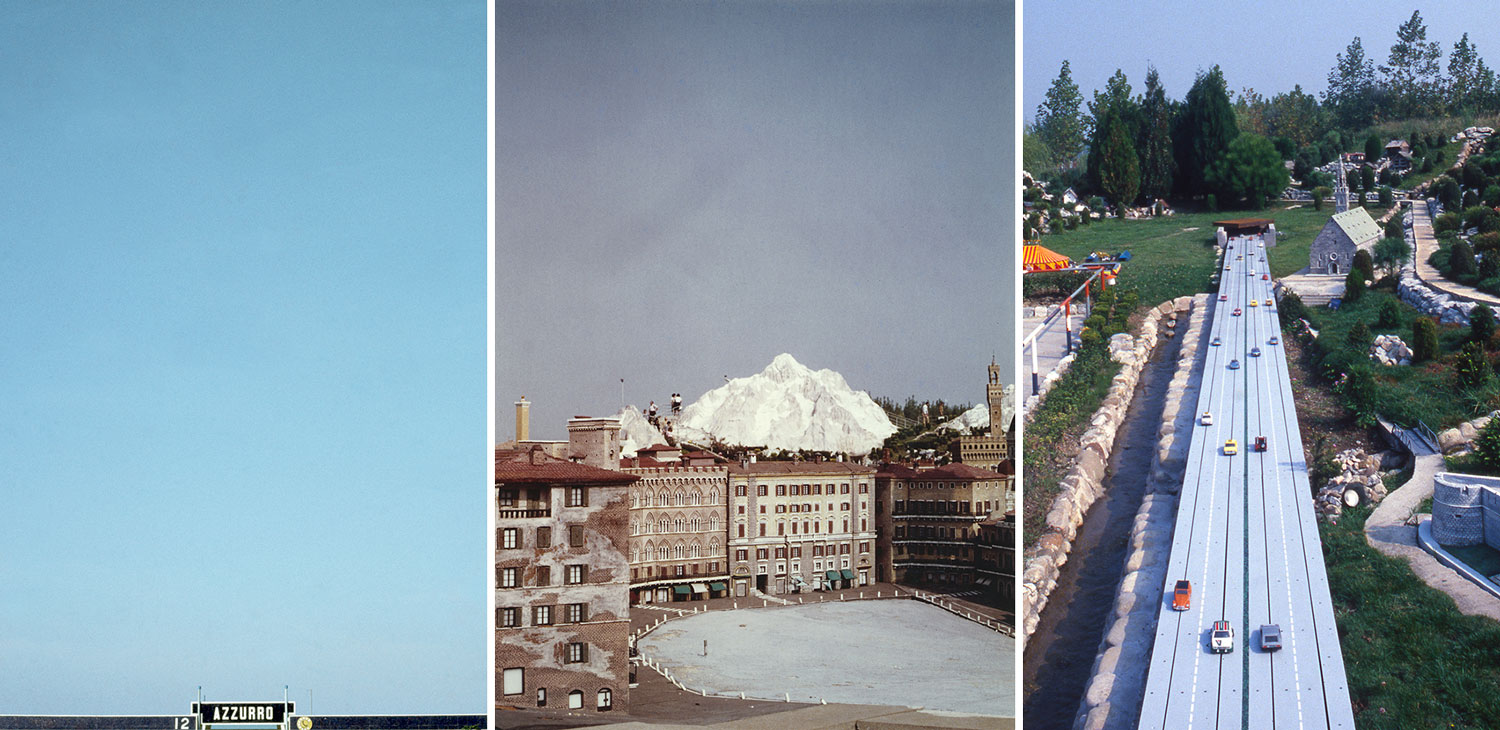

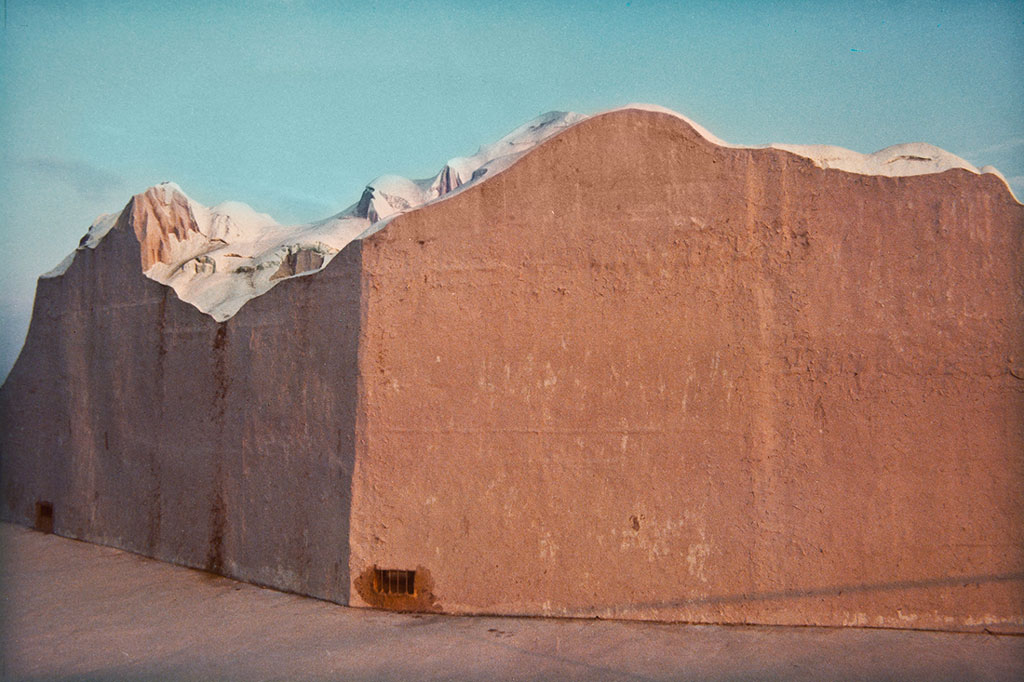

The exhibition “The Map and the Territory. Photographs from the 1970’s” at Jeu de Paume is the first retrospective of photographs taken outside his native Italy of Luigi Ghirri’s oeuvre in a museum outside of his native Italy. Luigi Ghirri took up photography seriously in 1970, at the age of 27. For the previous decade, he had worked as a surveyor in the towns and countryside of his native province of Reggio Emilia in Italy. Over the course of the next two decades, until his death at the age of 48, he made thousands of photographs out “in the field”. His subjects were commonplace, his approach to photography modest and unaffected. Reflecting on the nature of the medium, the language of images and their role in the making of modern identities, Ghirri charted the changing contours of modern life in a European culture poised between old and new. Ghirri worked solely in color, at a time when color photography was regarded with suspicion in mainstream artistic circles because of its closeness to amateur and commercial photography, and when black-and-white was synonymous with serious work in the medium. “I take photographs in color because the real world is not in black and white, and because color film has been invented” he wrote. He took his rolls of Kodachrome film to be developed in a normal processing lab in Modena, and returned to collect the small prints later. With this decision to embrace an unpretentious approach to the medium, he positioned his work away from the mainstream and closer to Conceptual Art. Throughout the 1970s, Ghirri’s work moved in different directions simultaneously rather than following a single linear route. He photographed a wide range of subjects, from suburban houses and gardens to beaches and fairgrounds, pages in an atlas, people looking at maps or posing for the camera. He arranged his photographs into groups, which he came to consider “open works”. Some were completed in a particular year and had clear parameters. Others were more open-ended, combining photographs taken over a number of years and in many different places. For the most important exhibition of his work to date, held in Parma in 1979 and titled “Vera fotografia”, Ghirri presented 14 different groups of photographs taken over the course of the decade. The exhibition at Jeu de Paume reprises the structure of the exhibition in Parma to show the different itineraries Ghirri followed. He worked for the most part outside, walking the streets of Modena and making what he called “minimal journeys” with his camera out to the suburbs. Occasionally he ventured further afield, on holiday trips to Amsterdam, Paris and the Swiss Alps. A small Canon camera in hand, he always had a project in mind as he surveyed his immediate environment. Amongst his most important early series are “Paesaggi di cartone” and “Colazione sull’erba”. In “Paesaggi di cartone”, he charted the ubiquity of the photographic image in the everyday environment. Throughout the decade, he extended this into a more extensive series called “Kodachrome”, which featured photographs of billboards, posters, postcards and images found on his journeys through the city. In “Colazione sull’erba” he looked closely at the anonymous architecture of the new suburbs and the neat gardens around the houses. In the early 1970s, Ghirri was immersed in a vibrant artistic milieu in Modena whilst continuing his professional work as a surveyor. He was affiliated with a group of young artists and writers that included Franco Guerzoni, Claudio Parmiggiani and Franco Vaccari, who shared affinities with contemporary art practices in Europe and the United States, notably Pop and Conceptual Art and their questioning of the status of images and the nature of perception. However, photography was always more than an analytical tool for Ghirri. It was “a great adventure into the world of thinking and looking”, a marvellous medium for describing and transforming the visible world. He continued to look closely at his immediate environment in “Catalogo”, a series of photographs of surfaces on the walls of the city and the suburbs. He mapped all the advertising images on the perimeter wall of a racing track in Modena, and in the series “Diaframma 11, 1/125, luce naturale” charted the formative role photography played in shaping modern life and modern identities; the way people look, and are looked at. In 1973, at the moment he decided to give up making charts and maps as a surveyor in order to focus full-time on his work as a photographer, he returned to the pages of an atlas to make “Atlante”, an important work in Ghirri’s journey through signs and images. The many years that Ghirri worked as a surveyor, measuring distances and elevations, delineating boundaries and spaces, left a distinctive mark on his photography. His subjects are almost always photographed straight-on, and strong vertical and horizonal lines recur throughout his work. By the mid-1970s, the horizon line separating land and sea from sky became increasingly prominent, marking the difference between measured and measureless space. Ghirri was drawn to places shaped by humankind, yet his photographs are mostly without people. His focus is on ordinary objects and places frequented by people for leisure or recreation, such as holiday locations on the Adriatic coast or the Swiss lakes. A sense of latency, of a world that is waiting, is palpable, not least in the many photographs Ghirri took of places made for people to sit and take in the view. These form part of an important series called “Vedute”, an open-ended essay on the nature of vision that includes a multiplicity of different views and reveals his preoccupation with frames, mirrors and reflections. In 1978, Ghirri published his first and most important book, “Kodachrome”. Condensing his many subjects and interests with precision and poetry, Kodachrome stands as one of the most singular photographic books of the period. Ghirri was drawn to places where public experience was based on an enthusiastic complicity with a fiction, and the title of the group of photographs “Il Paese dei balocchi” (1972-79) comes from “The Adventures of Pinocchio” a book where the everyday is replaced by a make-believe world. He spent many weekends visiting a fairground in Modena. He preferred to photograph behind the scenes there, revealing the constructions that underpin the artifice. The crowd for whom the fiction is made are absent, and the fairground takes on an almost dreamlike, metaphysical dimension. Ghirri’s interest in the popular appetite for doublings and simulations also led him to photograph portraits of famous people in a wax museum in Amsterdam, dinosaurs in an amusement park in Verona and dioramas in a natural history museum in Salzburg. At first glance the details of dioramas resemble actual landscapes. A closer look reveals them to be representations of landscapes, pictures of pictures. In the series “Still Life”, he reframed paintings and mirrors that he encountered in the flea market in Modena, as well as photographing pages from amateur photography magazines for the album “Slot Machine”. Another key aspect of the photographic image is that it almost always involves a significant shift in scale. Ghirri emphasised this in the series “In scala”, where he photographed miniature versions of famous buildings in a theme park, a tourist destination that is already a scaled-down version of somewhere else.

Info: Curator: James Lingwood, Jeu de Paume, 1 place de la Concorde, Paris, Duration: 12/2-2/6/19, Days & Hours: Tue 11:00-21:00, Wed-Sun 11:00-19:00, www.jeudepaume.org