ART CITIES:Frankfurt-Cady Noland

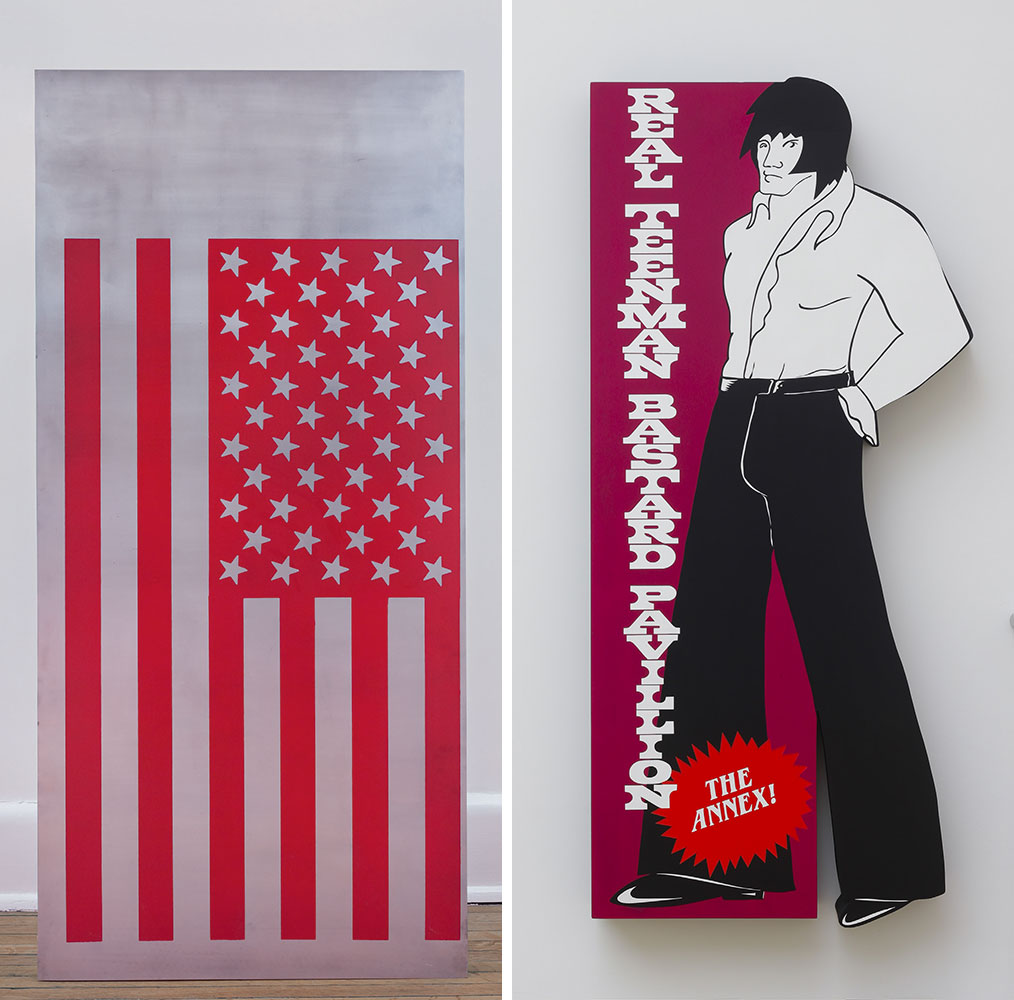

Working in collage, installation, sculpture, and screen printing, Cady Noland has created incisive works that challenge the American dream, suggesting that the ideal of upward mobility through hard work begets a culture of resentment in the face of celebrity culture and corporate influence on government. Barricades, beer cans, and bullet holes are some of the loaded objects and images that figure promi¬nently in her work. When positioned alongside an American flag or combined with images of famous or infamous cultural icons such as Patricia Hearst, Charles Manson, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, or Lee Harvey Oswald, the objects in Noland’s visual lexicon begin to hum with ideas and questions about the nature and origin of violence, power, and control; the role of fame in late-capitalist society; and the ways in which fear can steer democracy.

Working in collage, installation, sculpture, and screen printing, Cady Noland has created incisive works that challenge the American dream, suggesting that the ideal of upward mobility through hard work begets a culture of resentment in the face of celebrity culture and corporate influence on government. Barricades, beer cans, and bullet holes are some of the loaded objects and images that figure promi¬nently in her work. When positioned alongside an American flag or combined with images of famous or infamous cultural icons such as Patricia Hearst, Charles Manson, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, or Lee Harvey Oswald, the objects in Noland’s visual lexicon begin to hum with ideas and questions about the nature and origin of violence, power, and control; the role of fame in late-capitalist society; and the ways in which fear can steer democracy.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: MMK Archive

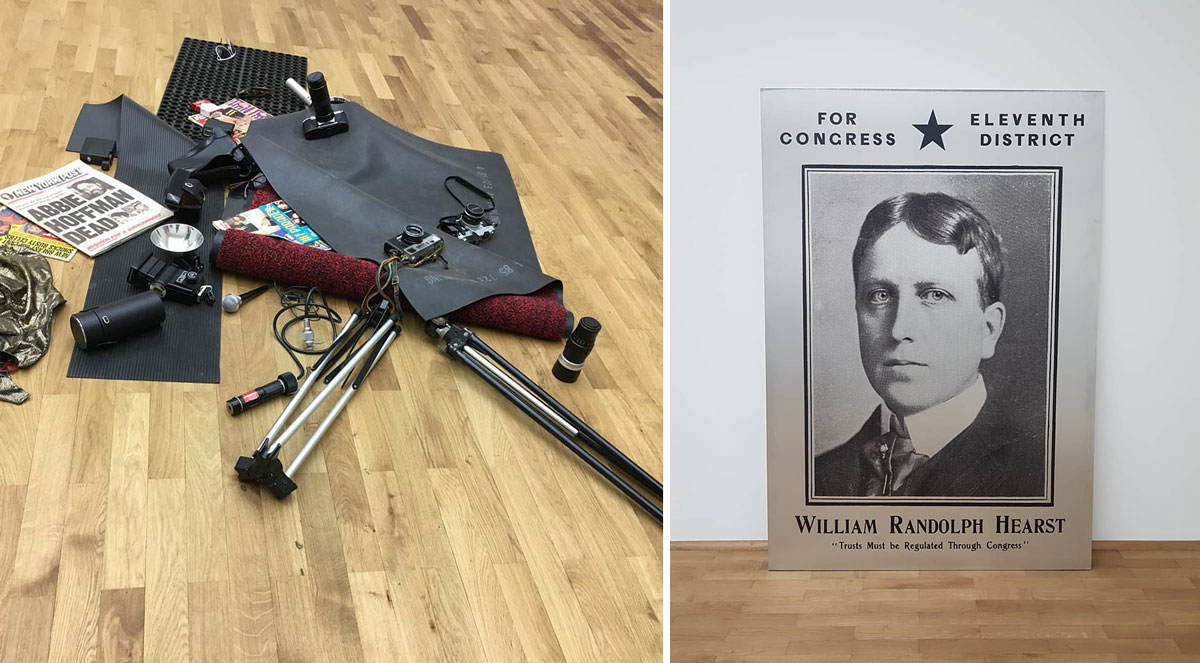

In her works, Cady Noland uncovers the violence we encounter every day in scenarios of spatial and ideological demarcation. She thus exposes the alleged neutrality of material and form. The supposedly clear distinction between objects and subjects becomes blurred, the unceasing interaction between them evident. A survey of Cady Noland at Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt, demonstrates how the overlapping of dream and nightmare is far from exclusive to the USA. Working in collage, installation, sculpture, and screen printing, Cady Noland has created incisive works that challenge the American dream, suggesting that the ideal of upward mobility through hard work begets a culture of resentment in the face of celebrity culture and corporate influence on government. Barricades, beer cans, and bullet holes are some of the loaded objects and images that figure prominently in her work. When positioned alongside an American flag or combined with images of famous or infamous cultural icons such as Patricia Hearst, Charles Manson, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, or Lee Harvey Oswald, the objects in Noland’s visual lexicon begin to hum with ideas and questions about the nature and origin of violence, power, and control; the role of fame in late-capitalist society; and the ways in which fear can steer democracy. As in other works by Cady Noland, the reduced, monochrome color of the aluminum cast and the heavy aluminum stands shifts the representational aspect of Cady Noland’s “Tower of Terror” (1993) into the realm of the abstract. By controlling and abstracting form and material Noland exposes the violent harshness that is inherent in the functional social contexts of these objects. Beneath the lustrous surface, the triple pillory sheds its outdated character. What remains is its purpose of humiliating people and exposing them to ridicule. It may be rendered all the more gruesome in the present, as public exposure for example through viral and uncontrollable distribution in social media, gains new actuality. In “Stockade, (1987-88), the title” designates a row of solid fence posts that forms a line of defense or encloses a prison. The formal reduction of color and form goes hand in hand with the substantive concretion and transmission of the enclosure cited in the title. The useless walker frames attached to the posts evoke an equally gruesome association with the physical restriction of access and participation. Interpretable in terms of the same relation-ship between an abstract entity (the stock market) and its concrete effect (social inequality) is the table published by the Internal Revenue office in New York, which is used to calculate income tax and immediately reveals an individual’s status in a society. The objects presented in “Model With Entropy” (1984) are used, worn, and covered with inscriptions. Hung side by side on a baseball bat, they form a bodiless trophy. The helmet no longer protects the football player’s head, the book is no longer being read, no body is being held securely in place by the safety belt, there is no hand in the glove, and the air has leaked out of the basketball. The model, which may have been meant to illustrate a theory, appears exhausted, devoid of energy, worn out. The world of sports, with its ideals, its cult of the body, and its division into winners and losers, has outlived its purpose as a social model of society. Perhaps this is the change from one condition to another that is suggested in the concept of entropy. “Untitled (SLA)” (1989) presents a shadowy image of a torn newspaper photograph showing members of the radical left-wing revolutionary organization known as the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA), which was active in the USA from 1973 until 1975. The group was led by the African-American Donald DeFreeze, alias “General Field Marshal Cinque,” who called himself Joseph Cinqué, in memory of the man who led a rebellion of slaves in 1839. The SLA published a manifesto entitled “Symbionese Liberation Army Declaration of Revolutionary War & Symbionese Program” in which it defined the Symbionese Army as a complex of various bodies and organisms and as a union of all left-wing, feminist, and anti-capitalist beliefs. Its symbol, the seven-headed cobra, is based on the principles of Kwanzaa, a popular week-long festival celebrated by African Americans in the US. The heads represent unity, self-determination, collective work and responsibility, cooperative economics, purpose, creativity, and faith. The group waged guerilla war and attracted considerable media attention through the kidnapping of Patty Hearst. “Tanya as a Bandit” (1989) shows an enlarged version of the staged photograph with which Patty Hearst publicly announced her affiliation with the SLA. The photo caused a media sensation in 1974, as Hearst, the granddaughter of William Randolph Hearst, despite being kidnapped by the SLA, joined the group as “Tanya” during the course of her captivity. Hearst named herself after Tamara Bunke, an East - German guerilla fighter and comrade of Che Guevara. Hearst, the cobra symbol, and another weapon are cut out, as if the aluminum plate still represented the original newsprint. The news report in which Hearst is described as “NOW A SUSPECT” after having fired her weapon wildly following the failed robbery of a sporting goods store in Los Angeles on May 16, 1974, serves as a kind of base for the image. “Untitled (William Randolph Hearst)” (1990) is a large-scale portrait of the American media tycoon and multimillionaire William Randolph Hearst. As the primary rival of Joseph Pulitzer, Hearst established the form of sensationalist reporting which became known as the “yellow press” towards the end of the nineteenth century. By putting together a chain of nearly thirty newspapers in all regions of the United States, he established the world’s largest newspaper and magazine empire. The sensationalistic journalism that typified his publications became the dominant narrative form in the media industry. Yet Hearst’s attempts to build a political career remained unsuccessful. In “Celebrity Trash Spill” (1989), cigarette packs, sunglasses, newspapers and clothing , are all symbols of the culture of celebrity and consumption , lie carelessly strewn over demolished camera equipment. In its event character, the work assumes the immediacy of a crime scene. The title page of the New York Post of April 13, 1989, announces the death of Abbie Hoffman. A co-founder of the Youth International Party (“Yippies”) and a member of the pacifist group known as the Chicago Seven, the activist and anarchist gained attention in the 1960s through prominent protest marches, and was regarded as an icon of the counterculture and the anti-war movement.

Info: Curator: Susanne Pfeffer, Museum für Moderne Kunst, Domstraße 10, Frankfurt am Main, Duration: 27/10/18-31/3/19, Days & Hours: Tue & Thu-Sun 10:00-18:00, Wed 10:00-20:00, www.mmk.art