ART CITIES:Frankfurt-Victor Vasarely

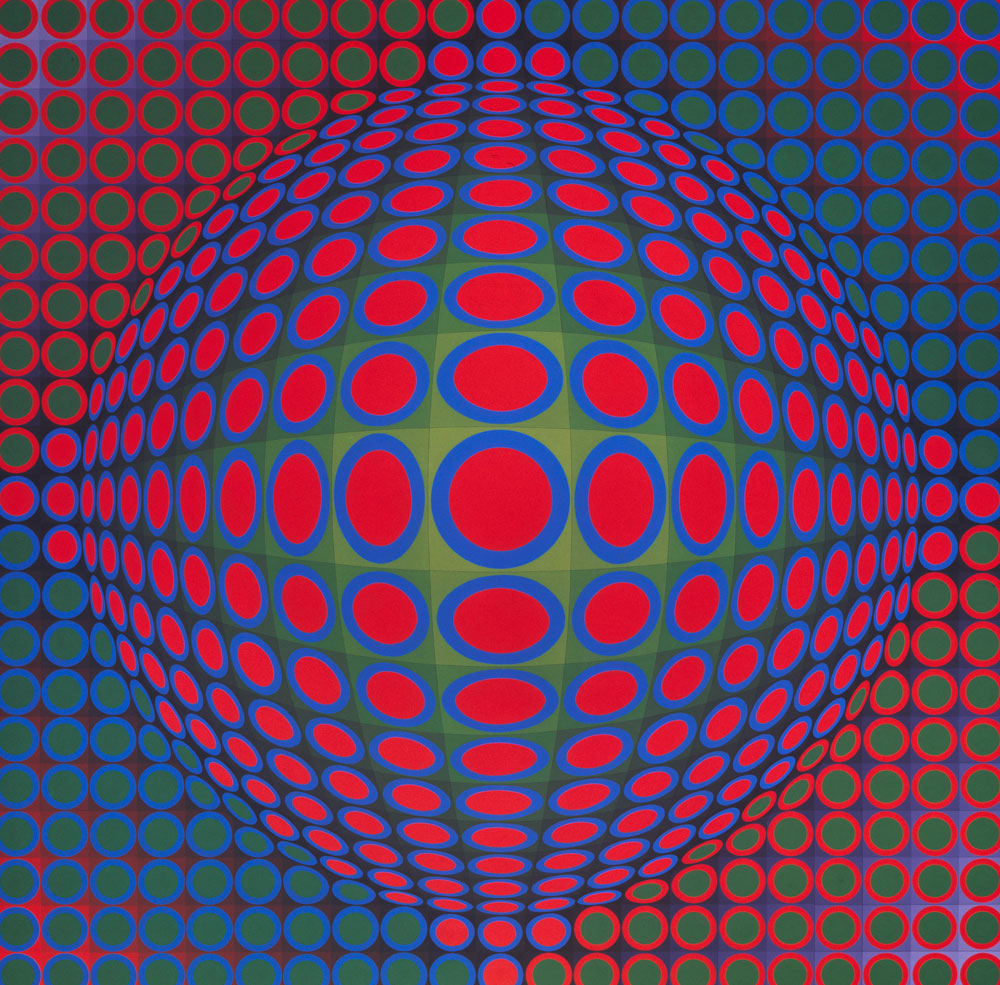

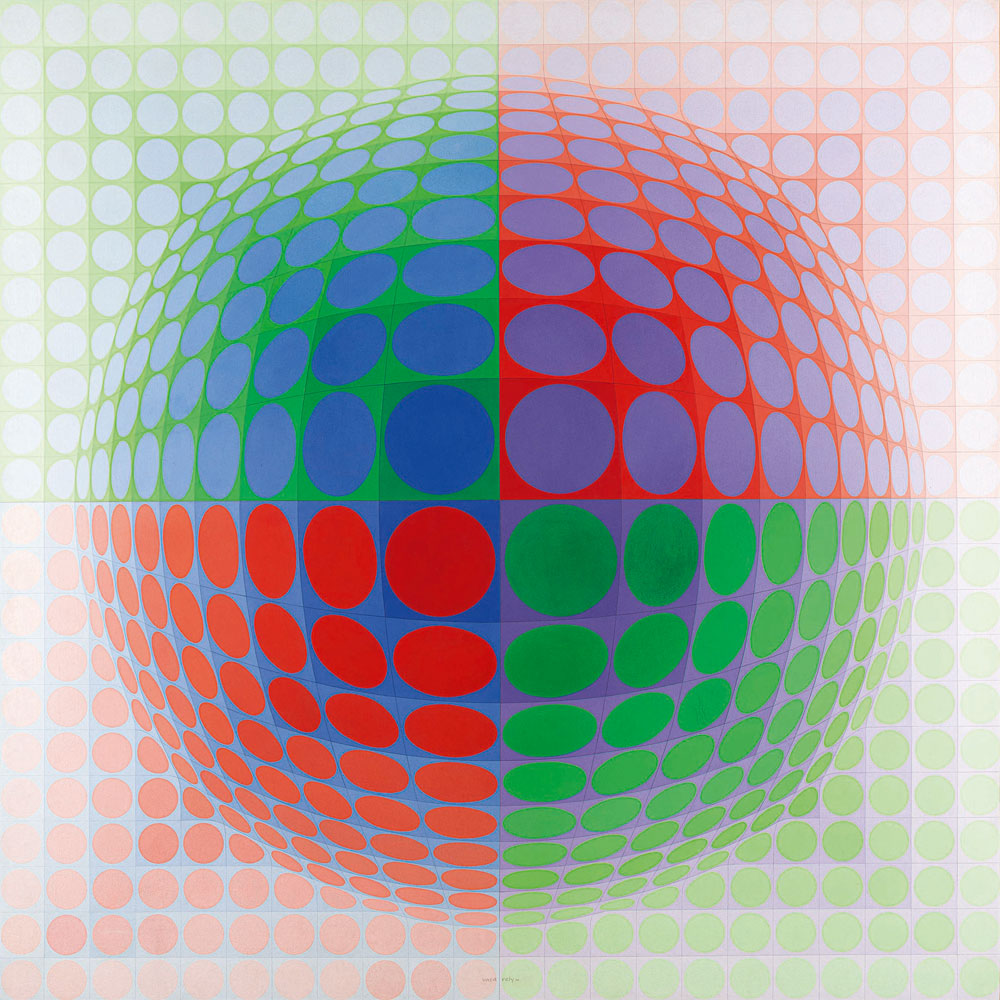

Victor Vasarely is one of the most crucial representatives of the 20th Century art, whose pictorial language has taken root in the collective memory without having been exactly located by art history. Vasarely’s origins as an artist are marked by his encounter with early modernism. He was influenced by theories of the Bauhaus and suprematism. His later technoid and psychedelically colorful works, which pushed into space, were aimed at deceiving the viewer’s perception.

Victor Vasarely is one of the most crucial representatives of the 20th Century art, whose pictorial language has taken root in the collective memory without having been exactly located by art history. Vasarely’s origins as an artist are marked by his encounter with early modernism. He was influenced by theories of the Bauhaus and suprematism. His later technoid and psychedelically colorful works, which pushed into space, were aimed at deceiving the viewer’s perception.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Städel Museum Archive

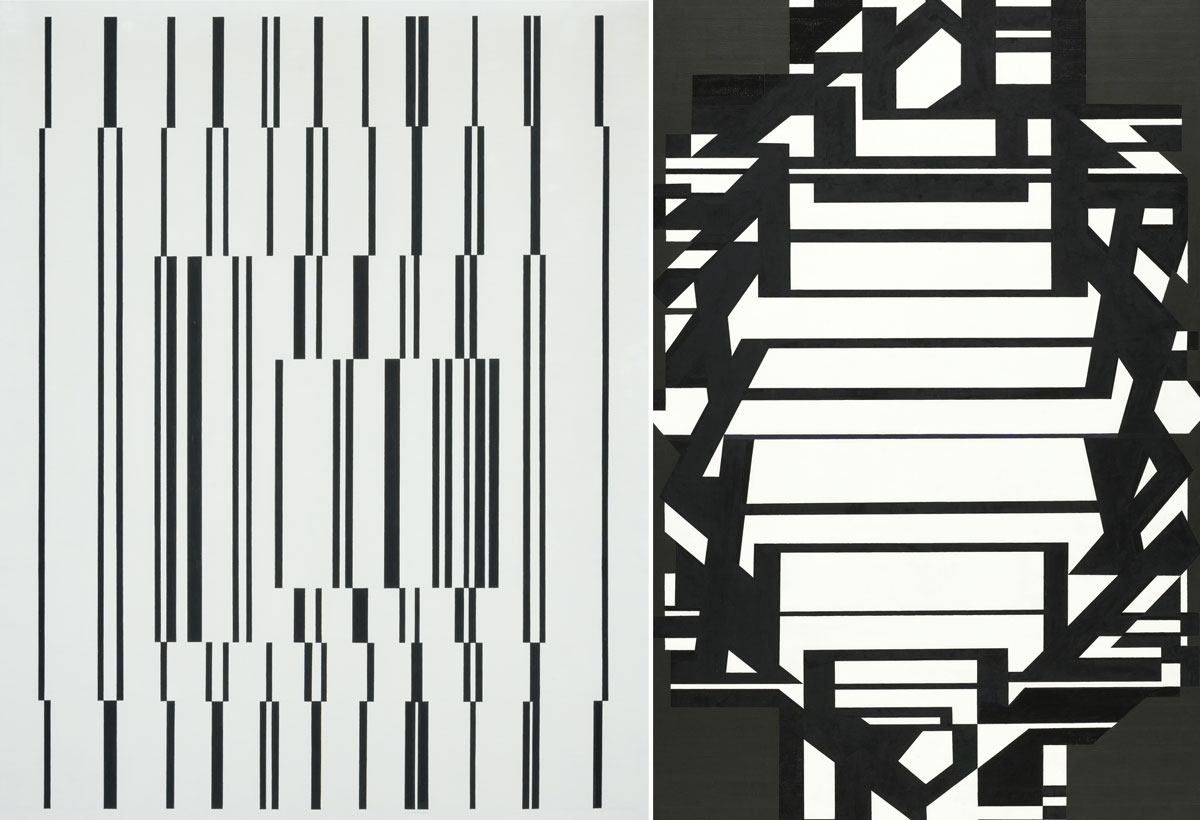

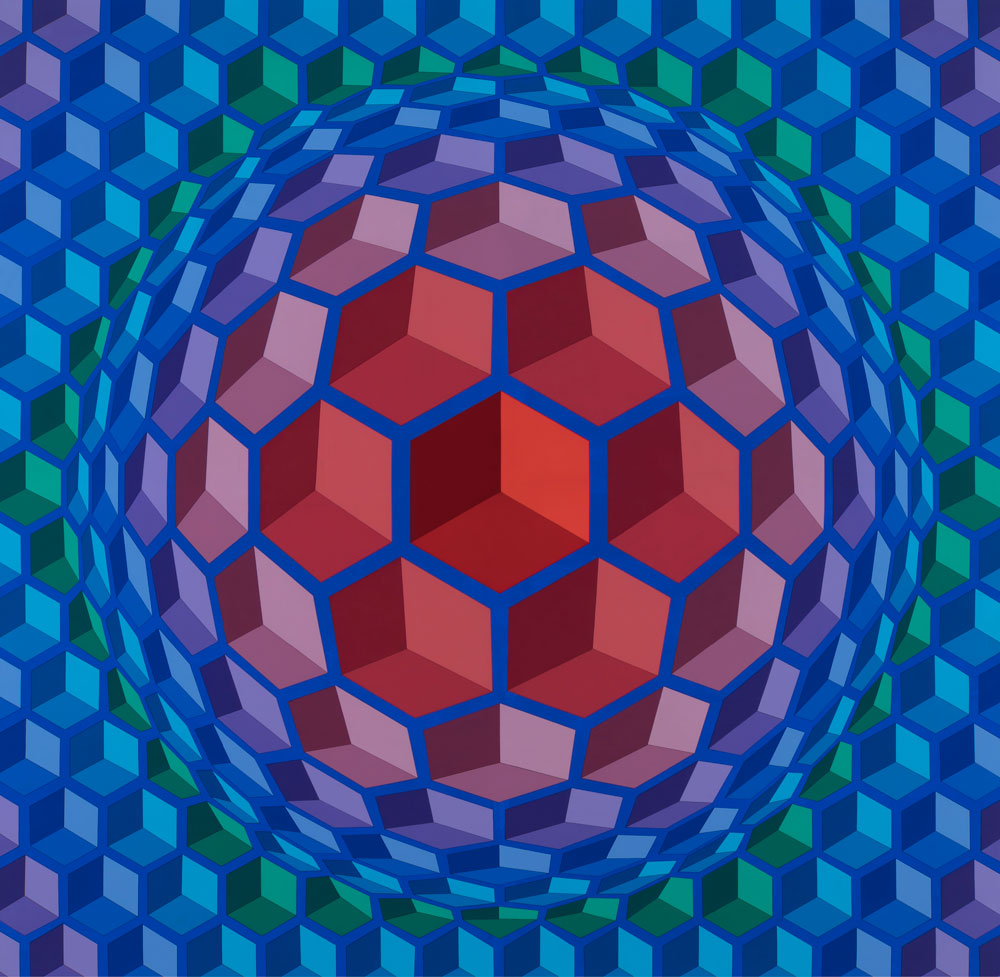

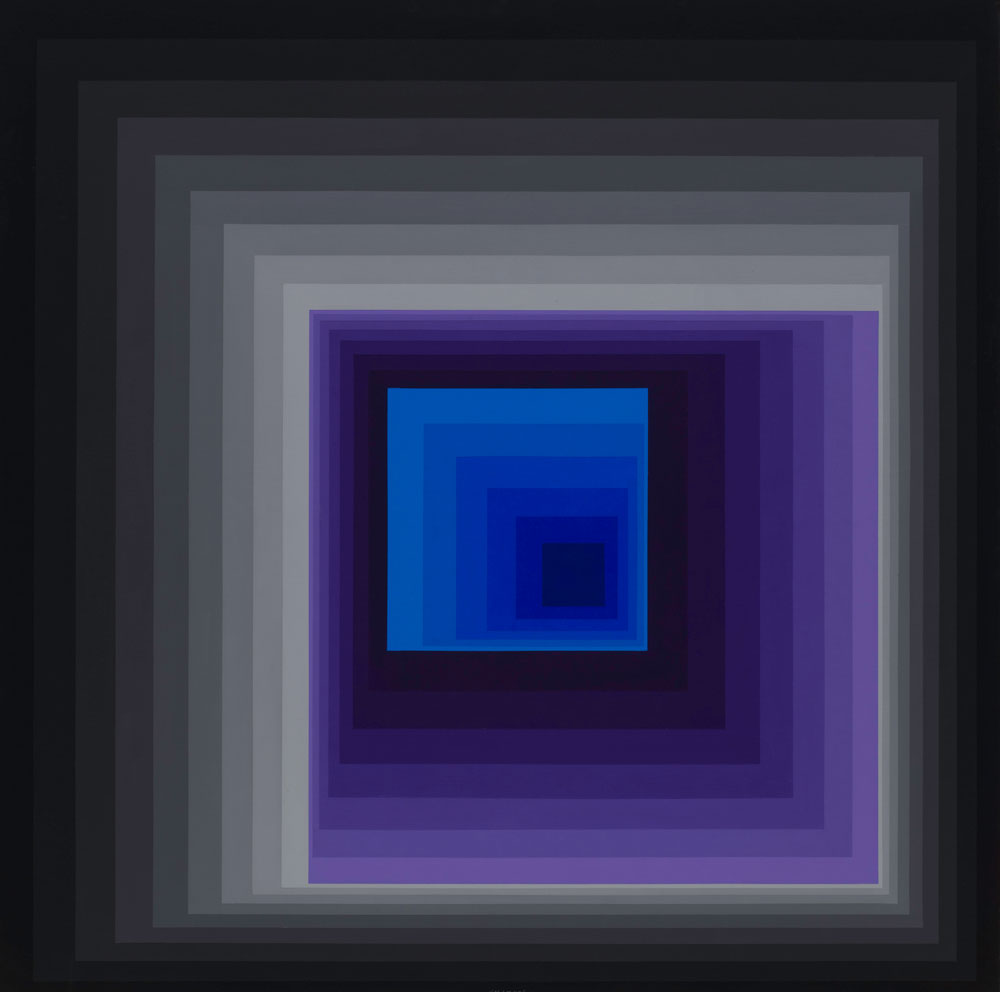

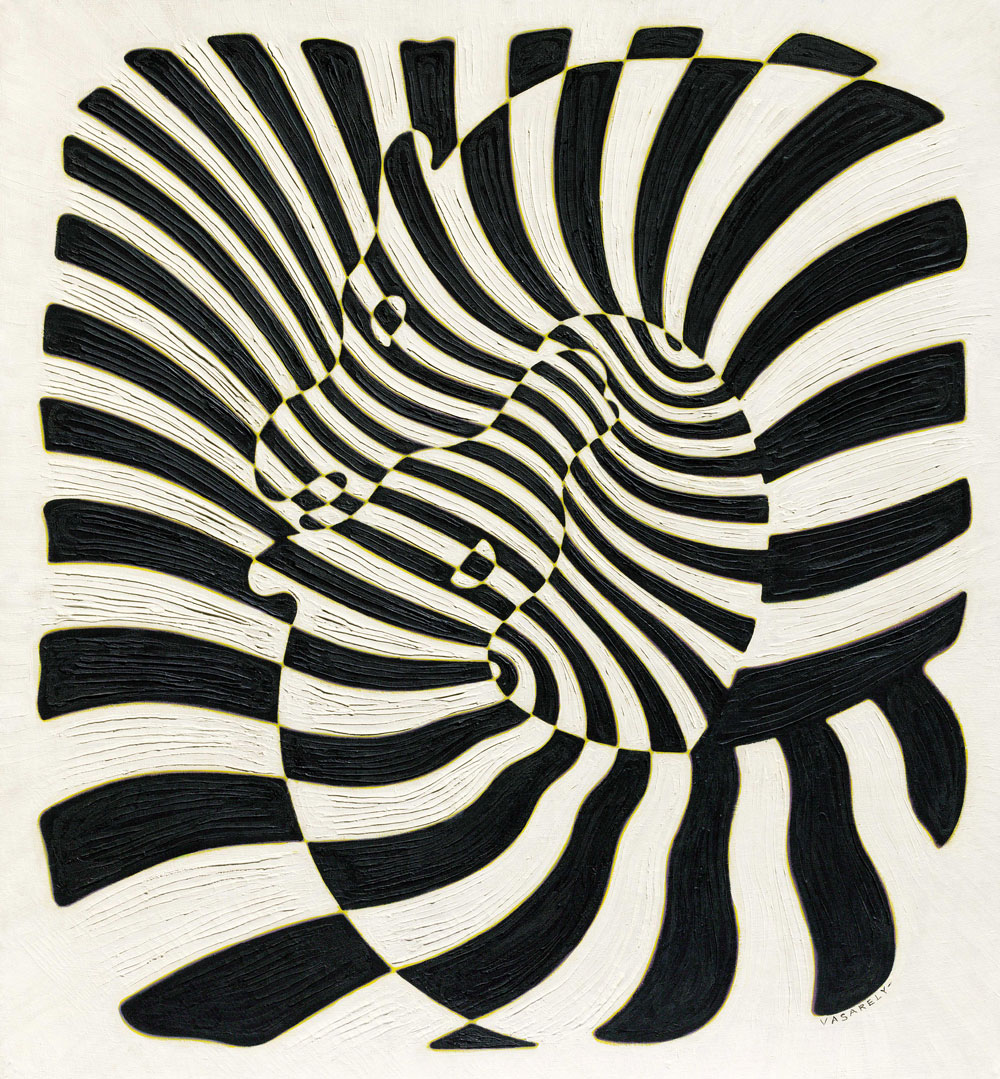

Spreading his works in the form of multiples and editions made Vasarely’s works omnipresent. The popularity he strove for, concerned with a democratisation of art, also made them a mass product—in the best and in the worst sense. If we read his labyrinthine compositions, his illusionist works, the abysses of his early oeuvre, and his primarily colorful Op Art pictures within the context of their time as regards both painting and content, we will come to understand his art as a fascinating testimony to modernism’s project of the century in all its contradictory nature. The retrospective “Victor Vasarely. In the Labyrinth of Modernism” presents the founder of the Op Art of the 1960s with 100 works. Victor Vasarely’s oeuvre, however, spans more than 60 years and makes use of the most diverse styles and influences: Key works of all phases of his production trace the development of the once-in-a century artist. Often reduced to his Op Art, the artist forged a bridge between the early modernism of Eastern and Central Europe and the Avant-Gardes of the 1960s in the West. He drew on traditional media and genres throughout his career, incorporating the multiple, mass production, and architecture into his complex work in the 1950s. The exhibition also looks back at Vasarely’s beginnings as an artist with such works as “Hommage au carré” (1929) or figurative paintings like “Autoportrait” (1944). The selection spans from early works like “Zèbres” (1937) and his Noir-et-Blanc period of the 1950s to the main works of Op Art such as the “Vega” pictures of the 1970s. The wide-ranging retrospective understands itself as a rediscovery of a crucial twentieth-century artist who reflects modernism in all its complexity like no other. The exhibition “Victor Vasarely. In the Labyrinth of Modernism”, which highlights the origins and development of the artist’s work, follows a reverse chronology. The visitor first comes upon Vasarely’s key works of the 1970s and 1960s, before he is guided through his varied oeuvre back to his early production of the 1930s and 1920s. The exhibition starts in the basement of the Städel Museum with the dining hall of the Deutsche Bundesbank designed by Vasarely and his son Yvaral, which was specially dismantled for the exhibition. The work impressively exemplifies the artist’s endeavour to extend his work from the canvas into space and to penetrate into the quotidian world in this way. Vasarely’s reproducible pictorial system opened up the possibility of a democratic dissemination of his art. With his architectonic integrations and multiples, like “Kroa Multicolor” (1963-68) or “Pyr” (1967), he, following in the tradition of Bauhaus, pursued the goal to intervene creatively in the everyday realm. The year 1972 found him at the peak of his career, his work omnipresent. He not only designed the logo for the Olympics but was also commissioned to go over the brand logo by Renault. Subsequently, the visitor comes upon Vasarely’s psychedelically colorful “Vega” series. These compositions still define the image of op art and the artist today. The cuboids, spheres, and rhombi of the series push their way into space in a trompe-l’oeil-like manner. Vasarely achieved this visual effect by a systematic distorting enlargement or reduction of individual squares or circles. In his two-times-two-meter-large work “Vega Pal” (1969) or in “Vega 200” (1968), the composition virtually shoves out from the picture as a dynamic hemisphere. Vasarely’s painting in oil or acrylics anticipates the computer-generated aesthetics of later generations. Starting from the “Vega” pictures, different visual axes afford insights into the artist’s Folklore planétaire period, powerful in both its forms and colors, and the invention of “unité plastique”, from which the works of this period emerged. Vasarely’s rigid pictorial system combines two basic geometric shapes, the square and the circle, with an equally clearly defined color spectrum comprising six local colors. The outcome is a pictorial method that allows to “produce” ever-new pictures requiring hardly any artistic decisions: the “plastic alphabet”. Within the open exhibition architecture, works like “Calota MC” (1967) or “CTA 102” (1965), which are based on the “plastic unity” principle and evolved from the “plastic alphabet”, enter into a dialogue with the “Vega” works as well as with those of the Noir-et-Blanc period preceding them. Apart from the reduction to black and white, this phase of Vasarely’s production saw the artist’s final turn towards geometric abstraction. The work “Hommage à Malevich” (1952-58) connects Vasarely’s early period and main work and presents itself as key for his entire oeuvre, with Malevich’s “Black Square” being set in motion, geometric shapes swivelling into space, and squares turning into rhombi, creating various levels. The artist’s “Photographismes”, which mark the beginning of his Noir-et-Blanc series and thus of op art are equally important for his pictorial language. Vasarely explored the black-and-white principle of photography and used it in his India ink drawings for his early “Photographismes”. Pursuing the story of the reverse chronology further, the second part of the exhibitin begins with three very different groups of works, which the artist worked on more or less in parallel, however. The pictures of the “Belle-Isle”, “Gordes-Cristal” and “Denfert” series are abstractions that still indicate their subjects in their titles. The works of these groups are not only independent but also wonderful modernist achievements in the best sense; their skilled compositions as well as their formal and intellectual austerity presage the perfectionist of future decades. The last part of the exhibition highlights Victor Vasarely’s beginnings in the milieu of the historical Avant-Gardes in Budapest. His first known works, such as “Hommage au carré” (1929). The modernist statics resting in itself was set in motion, albeit only ethereally at the time, with differently coloured squares subtly converging when receding into the depth of the picture plane. Yet even here, there can be doubt that the artist is not concerned with the merely visual, with an optical game.

Info: Curators: Dr. Martin Engler and Dr. Jana Baumann, Städel Museum, Schaumainkai 63, Frankfurt am Main, Duration: 26/9/18-13/1/19, Days & Hours: Tue-Wed & Sat-Sun 10:00-18:00, Thu-Fri 10:00-21:00, www.staedelmuseum.de