ART-PRESENTATION: Nancy Spero-Paper Mirror

For Nancy Spero, who died in 2009 at the age of 83, choices of material, form, method, and subject matter were always political. Her radical body of work explores issues of subjugation, brutality and the abuse of power. She created an identity through the acts of borrowing and disguise. In early work, texts as well as images were enlisted from a wide range of sources to express alienation, disempowerment and physical pain.

For Nancy Spero, who died in 2009 at the age of 83, choices of material, form, method, and subject matter were always political. Her radical body of work explores issues of subjugation, brutality and the abuse of power. She created an identity through the acts of borrowing and disguise. In early work, texts as well as images were enlisted from a wide range of sources to express alienation, disempowerment and physical pain.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Museo Tamayo Archive

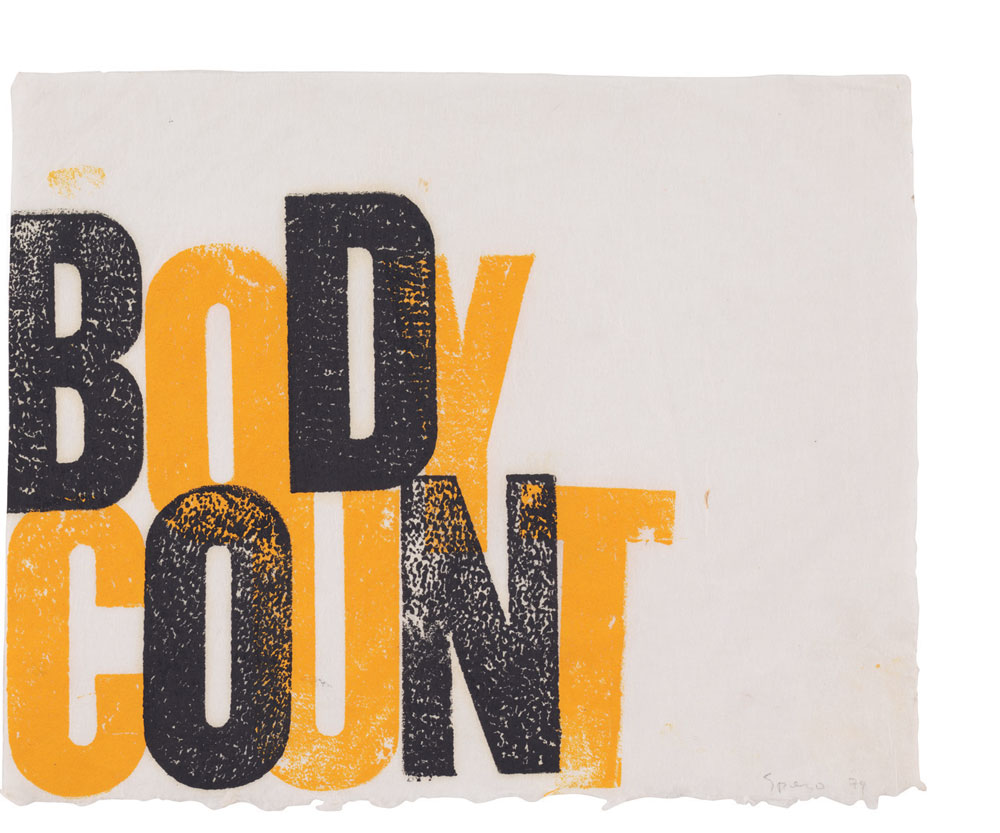

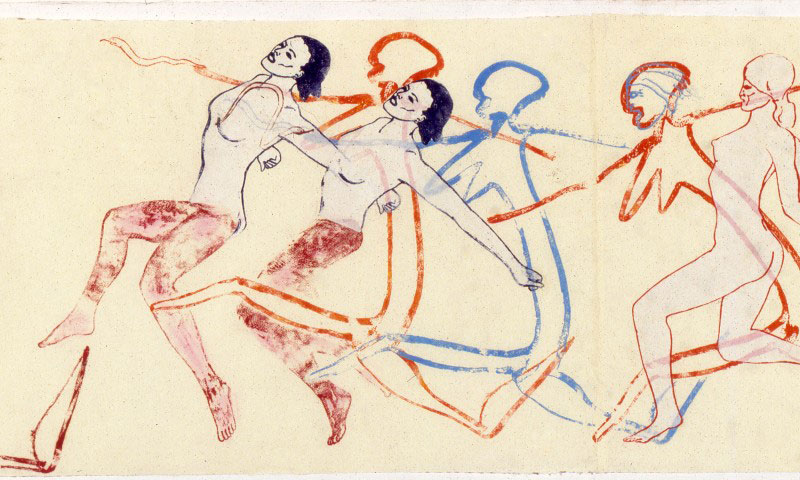

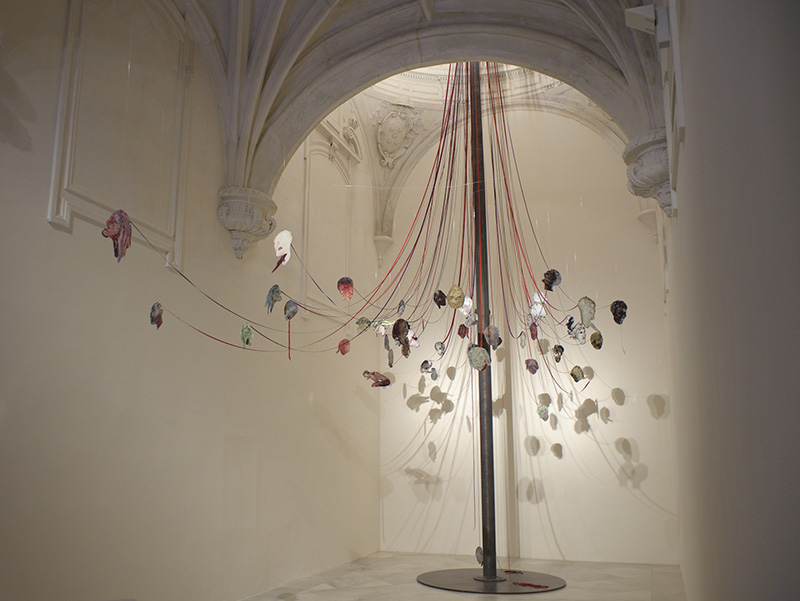

The exhibition “Nancy Spero: Paper Mirror” at Museo Tamayo is the first solo exhibition of Nancy Spero in Mexico and encompasses approximately 100 works from throughout Spero’s career, with elements from the series: “Black Paintings”, “War”, “Artaud”, “Licit Exp” and “Hours of the Nights” also numerous works from the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s populated by her transhistorical and cross-cultural cast of characters. Her last major work before her death in 2009, the installation Maypole: “Take No Prisoners”, that was originally created for the 2007 Venice Biennale, is installed in the Tamayo’s central atrium, this work fuses the “festive and the frightening,” and includes over 200 images of heads printed on aluminum and hanging from ribbons and metal chains. Nancy Spero consistently addressed oppression, inequality, and women’s social roles through both her art practice and activism. Her radical work made strong statements against war, male dominance and abuses of power, presenting compelling arguments for tolerance and a non-hierarchical society. Yet her work was never simplistically utopian, as she said “Utopia, like heaven, is kind of boring”. Born in Cleveland, Ohio, Spero graduated from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1949. Before settling with their three sons in New York in 1964, she and her husband, the painter Leon Golub, lived in Paris, where she created her first mature works, the “Black Paintings” (1959–65). For Spero, choices of material, form, mode, and subject were always political. After many years of working in oil on canvas, in 1966, she concluded that the language of painting was “too conventional, too establishment” and decided that from then on she would work exclusively on paper. Her first cycle of work on paper, the “War” Series (1966-69), was motivated by her outrage over American atrocities in Vietnam, gouache-and-ink paintings that express “the obscenity of war” including through depictions of sexualized bombs. The “Artaud Paintings” followed in 1969-70: handwritten fragments transcribed from the French poet Antonin Artaud’s writings, collaged with painted images of androgynous figures and phallic tongues. In reading Artaud, Spero coined the term “victimage” making a parallel between Artaud’s language and her feeling of the “loss of tongue” as a female artist in a male-dominated art world. Wanting to expand further into space beyond conventional formats, Spero’s “Codex Artaud” series (1971-72) combines typewritten excerpts of Artaud’s writing with collaged and painted images to make extended scroll-like works alluding to Egyptian hieroglyphics and papyrus scrolls. Spero experienced intense isolation and anger because of her invisibility as a female artist and became active in groups advocating women’s advancement in the arts. In 1972, she cofounded the first independent women’s art venue in the United States, A.I.R. Gallery. Through exhibitions at A.I.R. and elsewhere, Spero developed a vocabulary of female protagonists that run, dance, jump, and crawl across her panels and sheets in scroll-like formations. In the mid-70s, Spero proclaimed that women would be the “protagonists” of all her future work. She sought to “view women and men by representing women, not just to reverse history, but to see what it means to view the world through the depiction of women”. Around the same time, she began transferring her painted figures to zinc plates that permitted her to reproduce, repeat, and recycle images freely and infinitely, increasingly de-emphasizing text in her work, turning to “the language of gesture and movement”. Spero’s visual vocabulary mines diverse cultures, historical periods, and disciplines (mythology, folklore, art history, literature, and media) for representations of women as tragic and triumphant, degraded and powerful, victimized and liberated. In her late work, Spero drew upon a broad range of visual sources, from Etruscan frescos to fashion magazines, to create a figurative lexicon representing women from pre-history to the present. Her work, she stated, ‘speculates on a sense of possibility and comments upon immediate events, political, sexual and otherwise.

Info: Curator: Julie Ault, Museo Tamayo, Paseo de la Reforma 51, Bosque de Chapultepec, 11580 México City, Duration: 6/10/18-7/2/19, Days & Hours: Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00, http://museotamayo.org