PHOTO:Ansel Adams in Our Time

Ansel Adams is the rare artist whose works have helped to define a genre. Over the last half-century, his black-and-white photographs have become, for many viewers, visual embodiments of the sites he captured: Yosemite and Yellowstone National Parks, the Sierra Nevada, the American Southwest and more. These images constitute an iconic visual legacy, one that continues to inspire and provoke.

Ansel Adams is the rare artist whose works have helped to define a genre. Over the last half-century, his black-and-white photographs have become, for many viewers, visual embodiments of the sites he captured: Yosemite and Yellowstone National Parks, the Sierra Nevada, the American Southwest and more. These images constitute an iconic visual legacy, one that continues to inspire and provoke.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: MFA Archive

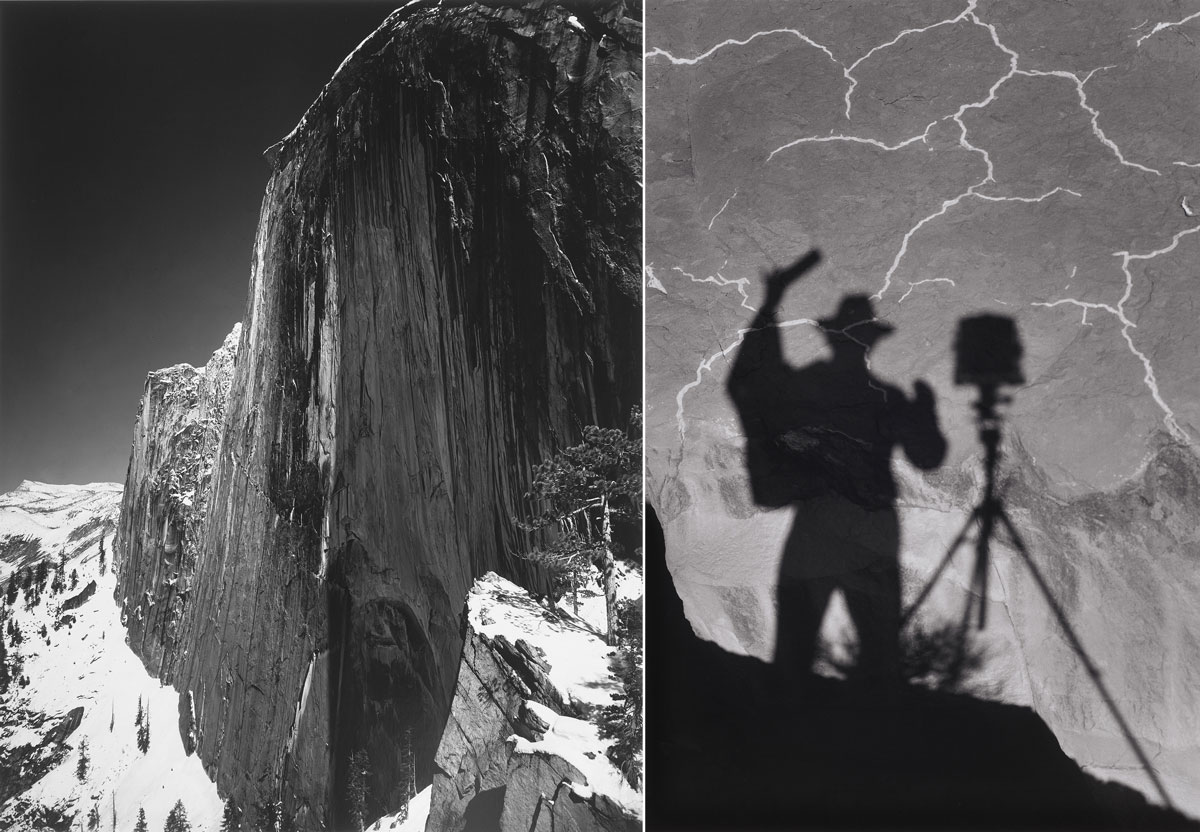

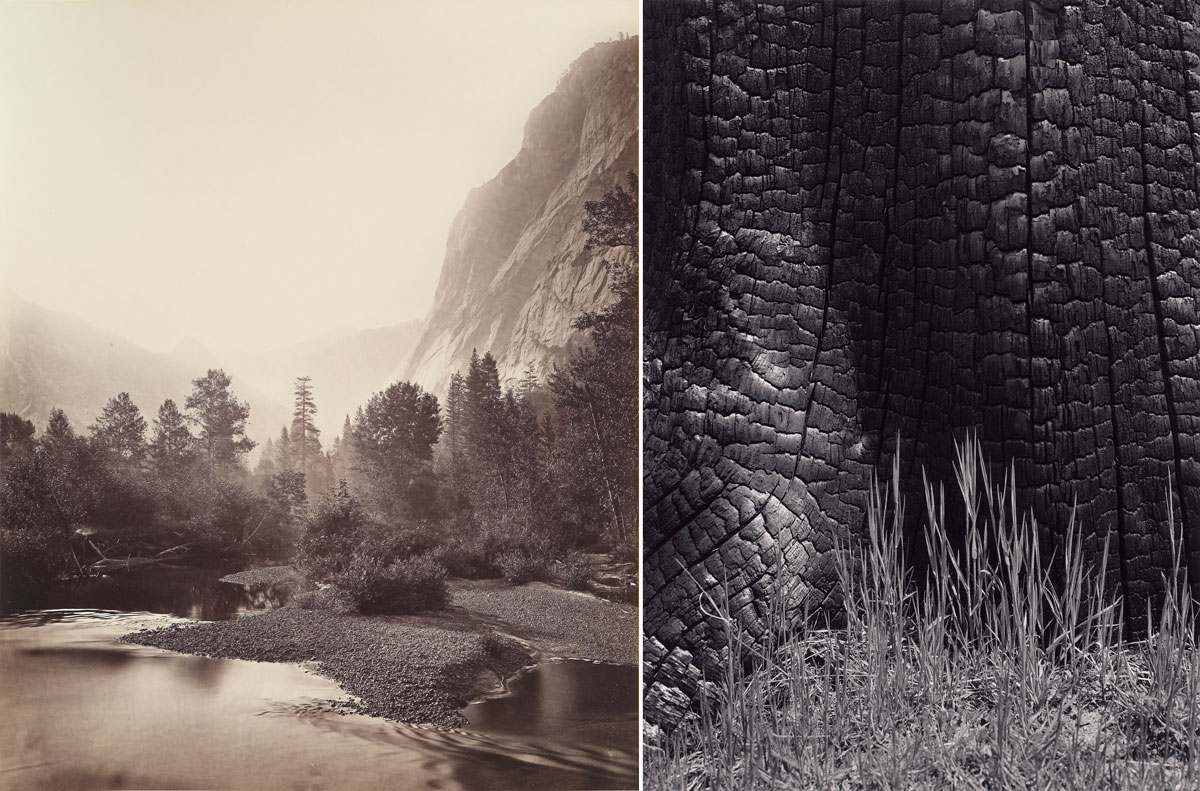

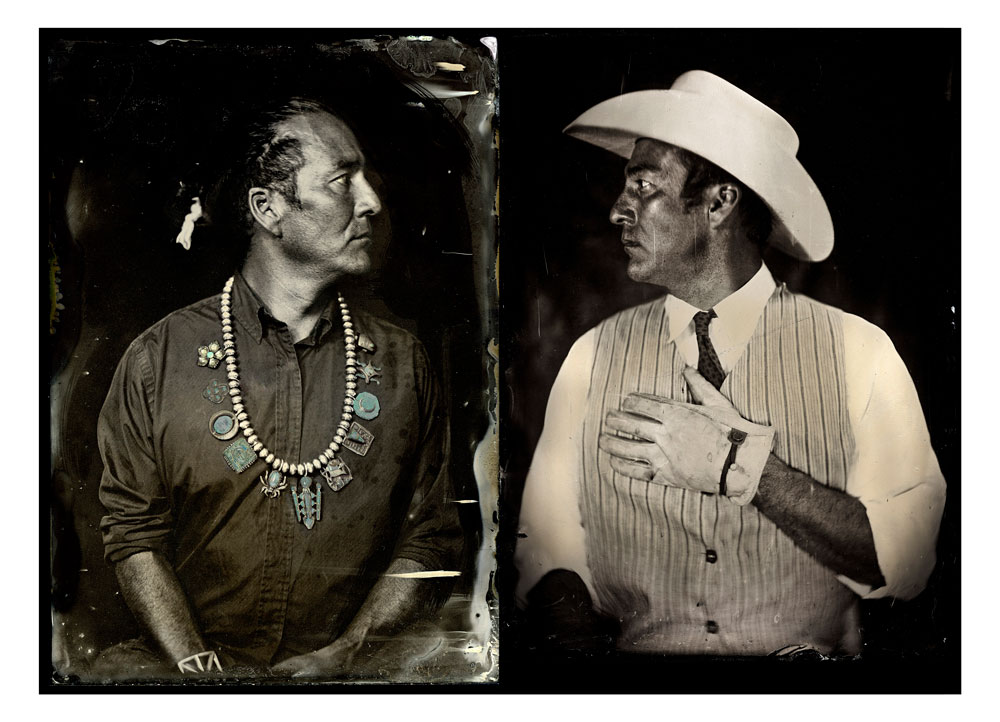

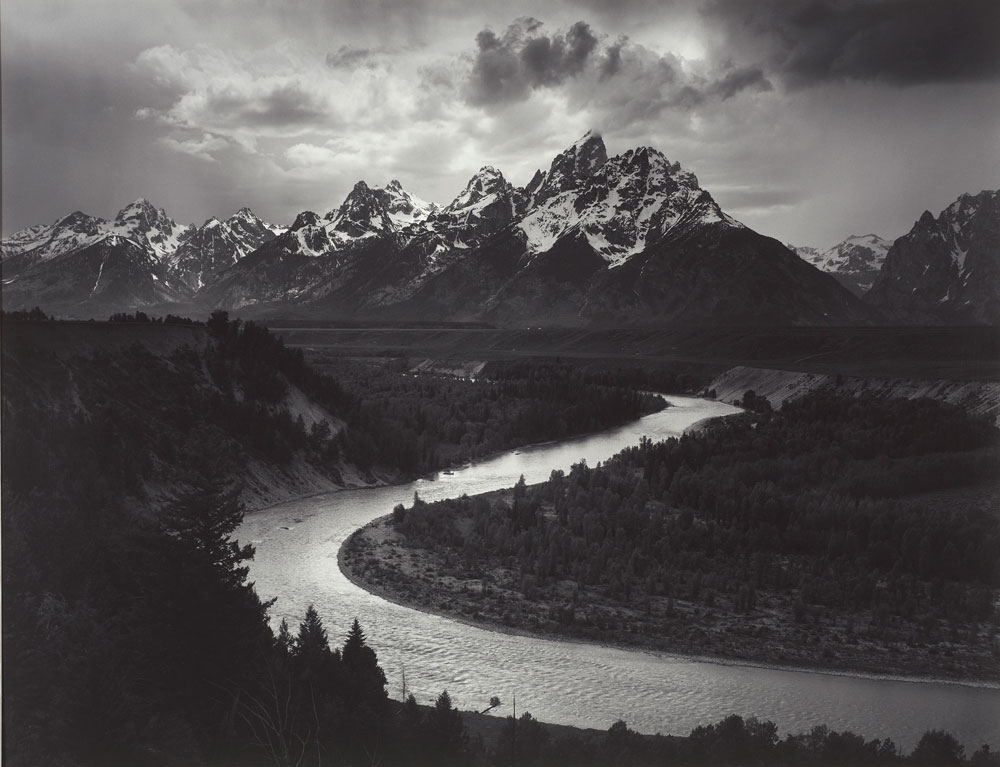

The exhibition “Ansel Adams in Our Time” offers a new perspective on one of the best-known American photographers by placing him into a dual conversation with his predecessors and contemporary artists. While crafting his own modernist vision, Adams followed in the footsteps of 19th Century forerunners in government survey and expedition photography such as Carleton Watkins, Eadweard Muybridge, Timothy O’Sullivan and Frank Jay Haynes. Today, photographers including Mark Klett, Trevor Paglen, Catherine Opie, Abelardo Morell, Victoria Sambunaris and Binh Danh are engaging anew with the sites and subjects that occupied Adams, as well as broader environmental issues such as drought and fire, mining and energy, economic booms and busts, protected places and urban sprawl. Approximately half of the nearly 200 works in the exhibition are photographs by Adams, drawn from the Lane Collection, which made the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA) one of the major holders of the artist’s work. Organized both thematically and chronologically into eight sections, the exhibition begins where Adams’ own photographic life began. Perhaps no place had a more lasting influence on him than Yosemite National Park, in his native California. Adams first visited Yosemite at age 14, bringing along a Kodak Box Brownie camera given to him by his father, and returned almost every year for the rest of his life. It was not only where he honed his skills, but also where he came to recognize the power of photographs to express emotion and meaning. Showcasing its spectacular granite peaks, lakes, rivers and waterfalls, Adams’ photographs of Yosemite have become virtually synonymous with the park itself. Adams, however, was not the first to take a camera into the mountains of California. He acknowledged his debt to the earliest photographers to arrive in the Yosemite Valley, including Carleton Watkins, who in the 1860s began to record scenic views with a cumbersome large-format camera and fragile glass plate negatives processed in the field. Watkins’ 19th Century photographs helped to introduce Americans “back east” to the nation’s dramatic western landscapes, while Adams’ 20th-century images made famous the notion of their “untouched wilderness.” Today, photographers such as Mark Klett are grappling with these legacies. Klett and his longtime collaborator Byron Wolfe have studied canonical views of Yosemite Valley by Adams and Watkins, using the latest technology to produce composite panoramas that document changes made to the landscape over more than a century, as well as the ever-growing presence of human activity. As a member of the Sierra Club, which he joined in 1919 at age 17, Adams regularly embarked on the environmental organization’s annual, month-long “High Trips” to the Sierra Nevada mountains. He produced albums of photographs from these treks, inviting club members to select and order prints. This precocious ingenuity ultimately led to the “Parmelian Prints of the High Sierras” (1927), one of the earliest experiments in custom printing, sequencing and distributing fine photographs. Sixteen of the 18 prints from the portfolio, including the iconic “Monolith – The Face of Half Dome”, are on view in the second gallery of the exhibition, which connects Adams’ innovations in marketing his views of the western U.S. to those of his predecessors. In the 19th Century, an entire industry of mass-marketing and distributing images of “the frontier” emerged, catering to a burgeoning tourist trade. In addition to engravings and halftones published in books, magazines and newspapers, photographs such as “Valley of the Yosemite from Union Point, No. 33” (1872) by Eadweard Muybridge were circulated through stereo cards, which allowed viewers to experience remote places in three dimensions when viewed through a stereoscope. Today, photography remains closely linked with scenic vistas of the American West. Creating works in extended series or grids, artists including Matthew Brandt, Sharon Harper and Mark Rudewel seem to be responding to the earlier tradition of mass-marketing western views, using photography as a medium to call attention to the passage of time and the changing nature of landscapes. The third section of the exhibition focuses on Adams’ hometown of San Francisco, which has long captured photographers’ imaginations with its rolling hills and dramatic orientation toward the water. The city’s transformation over more than a century, including changes made to the urban landscape following the devastating earthquake and fire in 1906 and the rise of skyscrapers in the later 20th century can be observed in the juxtaposition of panoramas by Eadweard Muybridge and Mark Klett, taken from the same spot 113 years apart. Adams’ images of San Francisco from the 1920s and 1930s trace his development into a modernist photographer, as he experimented with a large-format camera to produce maximum depth of field and extremely sharp-focused images. During the Great Depression, Adams also took on a wider range of subjects, including the challenging reality of urban life in his hometown. He photographed the demolition of abandoned buildings, toppled cemetery headstones, political signs and the patina of a city struggling during difficult times. One sign of hope for the future at the time was the construction of the Golden Gate Bridge, which began in 1933. Adams’ “The Golden Gate before the Bridge” (1932), taken near his family home five years before the bridge’s opening in 1937, is displayed alongside four contemporary prints from the “Golden Gate Bridge project” by Richard Misrach, taken from his own porch in Berkeley Hills. Placing his large-format camera in exactly the same position on each occasion, Misrach recorded hundreds of views of the distant span, at different times of the day and in every season. The series, photographed over three years from 1997 to 2000, was reissued in 2012 to mark the 75th anniversary of the Golden Gate’s landmark opening. The vast expanses of sky in Misrach’s works echo the focus on the massive cumulus cloud in the earlier photograph by Adams, who was fascinated with changing weather and landscapes with seemingly infinite space. Adams produced some of his most memorable images, among them: “Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico” (1941; print date: 1965–75)—during his frequent travels to the American Southwest. He was intrigued by the region’s distinctive landscape, brilliant sunlight and sudden dramatic storms, as well as its rich mix of cultures. Shortly after his first trip to New Mexico in 1927, Adams collaborated with author Mary Hunter Austin on the illustrated book “Taos Pueblo” (1930, Harvard Art Museums), for which he contributed 12 photographs that reflect his interest in Taos Pueblo’s architecture and activities. Adams shared Austin’s concern that the artistic and religious traditions of the Pueblo peoples were under threat from the increasing numbers of people traveling through or settling in the region. In contrast to the indigenous peoples of Yosemite, who had been forced out of their native lands many years earlier, Pueblo peoples were still living in their ancestral villages. On his return visits to the American Southwest, Adams often photographed the native communities, their dwellings and their ancient ruins. He also photographed Indian dances, which had become popular among tourists who came to be entertained and to buy pottery, jewelry and other souvenirs. Adams’ images of dancers, which emphasize their costumes, postures and expressions, therefore have a complex legacy, as he was one of the onlookers, though he carefully cropped out any evidence of the gathered crowds. Today, indigenous artists including Diné photographer Will Wilson, are creating work that responds to and confronts past depictions of Native Americans by white artists who traveled west to “document” the people who were viewed as a “vanishing race” in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries. The largest section of the exhibition examines the critical role that photography has played in the history of the national parks. In the 19th Century, dramatic views captured by Carleton Watkins and other photographers ultimately helped convince government officials to take action to protect Yosemite and Yellowstone from private development. Adams, too, was aware of the power of the image to sway opinions on land preservation. In 1941 Harold Ickes, Secretary of the Interior, hired Adams to make a series of mural-sized photographs of the national parks for the capital’s new Interior Building. Although his government funding was cut short by America’s entry into World War II and the murals were never realized, Adams felt so strongly about the value of the project that he sought financial assistance on his own. He secured Guggenheim Foundation grants in 1946 and 1948, which allowed him to travel to national parks from Alaska to Texas, Hawaii to Maine. Marked by a potent combination of art and environmental activism, the photographs he made spread his belief in the transformative power of the parks to a wide audience. Many contemporary artists working in the national parks acknowledge, as Adams did, the work of the photographers who came before them. But the complicated legacies of these protected lands have led some, including: Catherine Opie, Arno Rafael Minkkinen, Binh Danh and Abelardo Morell, to take more personal and political approaches to the work they are making in these spaces. Adams made his reputation mainly through spectacular images of “unspoiled” nature. Less well known are the photographs he produced of the more forbidding, arid landscapes in California’s Death Valley and Owens Valley, just southeast of Yosemite. Here, on the other side of the Sierra Nevada, Adams’ work took a dramatic detour. Fellow photographer Edward Weston introduced Adams to Death Valley, where he captured images of sand dunes, salt flats and sandstones canyons. Owens Valley, located to the west, was once verdant farmland, but was suffering by the 1940s, its water siphoned off to supply the growing city of Los Angeles. In 1943, Adams also traveled to nearby Manzanar, where he photographed Japanese Americans forcibly relocated to internment camps shortly after the U.S. entered World War II. Trevor Paglen, Stephen Tourlentes and David Benjamin Sherry are among the contemporary photographers who continue to find compelling subjects in these remote landscapes. Some are drawn to them as “blank slates” upon which to leave their mark, while others explore the raw beauty of the desolate terrain and the many, sometimes unsettling ways it used today—including as a site for maximum-security prisons and clandestine military projects. Adams’ photographs are appreciated for their imagery and formal qualities, but they also carry a message of advocacy. The last two sections of the exhibition examine the continually changing landscapes of the sites once captured by Adams. In his own time, the photographer was well aware of the environmental concerns facing California and the nation ,thanks, to his involvement with the Sierra Club and Wilderness Society. As his career progressed, Adams began to move away from symphonic and pristine wilderness landscapes in favor of images that showed a more nuanced vision. He photographed urban sprawl, freeways, graffiti, oil drilling, ghost towns, rural cemeteries and mining towns, as well as quieter, less romantic views of nature, such as the aftermath of forest fires—subjects that resonate in new ways today. For contemporary photographers working in the American West, the spirit of advocacy takes on an ever-increasing urgency, as they confront a terrain continually altered by human activity and global warming. Works by artists including: Laura McPhee, Victoria Sambunaris, Mitch Epstein, Meghann Riepenhoff, Bryan Schutmaat and Lucas Foglia bear witness to these changes, countering notions that natural resources are somehow limitless and not in need of attention and protection.

Info: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Avenue of the Arts, 465 Huntington Avenue, Boston, Duration: 13/12/18-20/2/19, Days & Hours: Mon-Tue & Sat-Sun 10:00-17:00, Wed-Fri 10:00-22:00, www.mfa.org