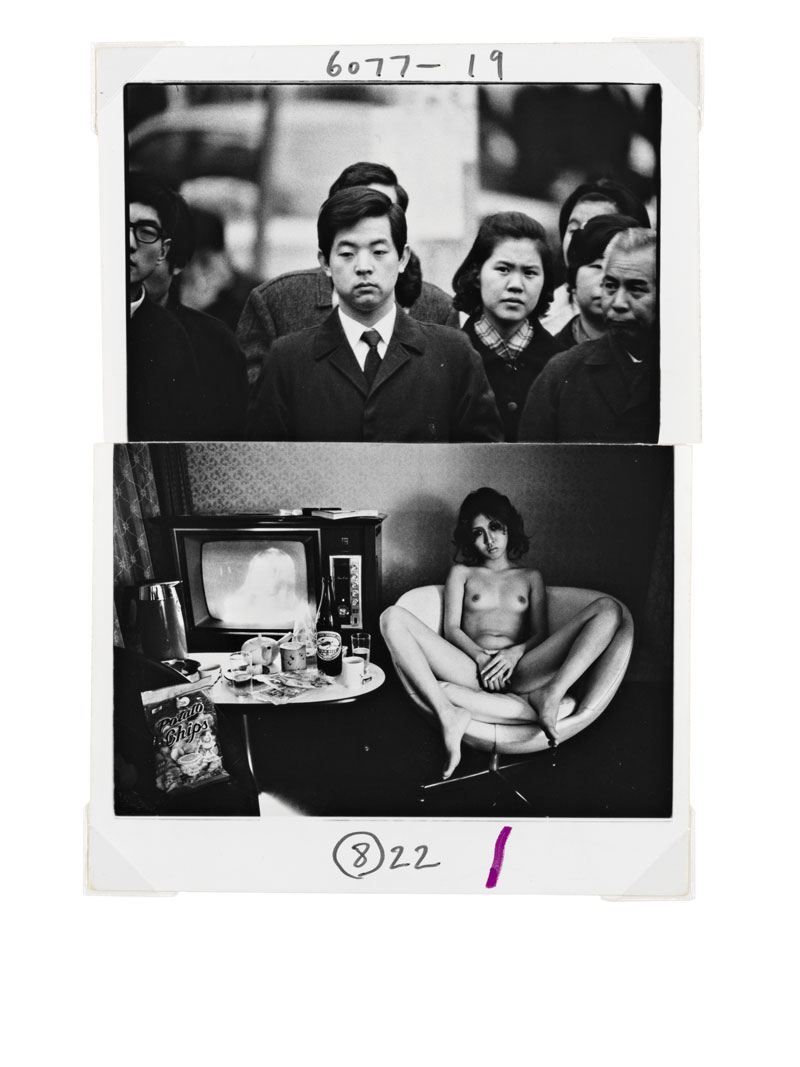

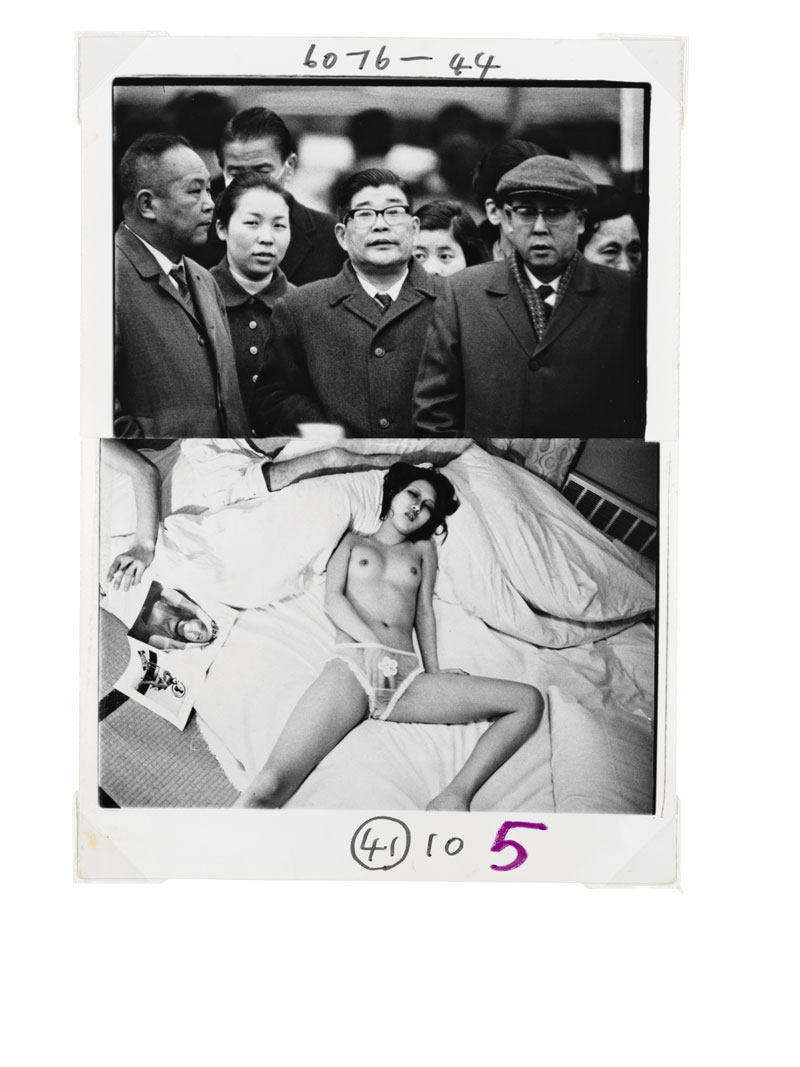

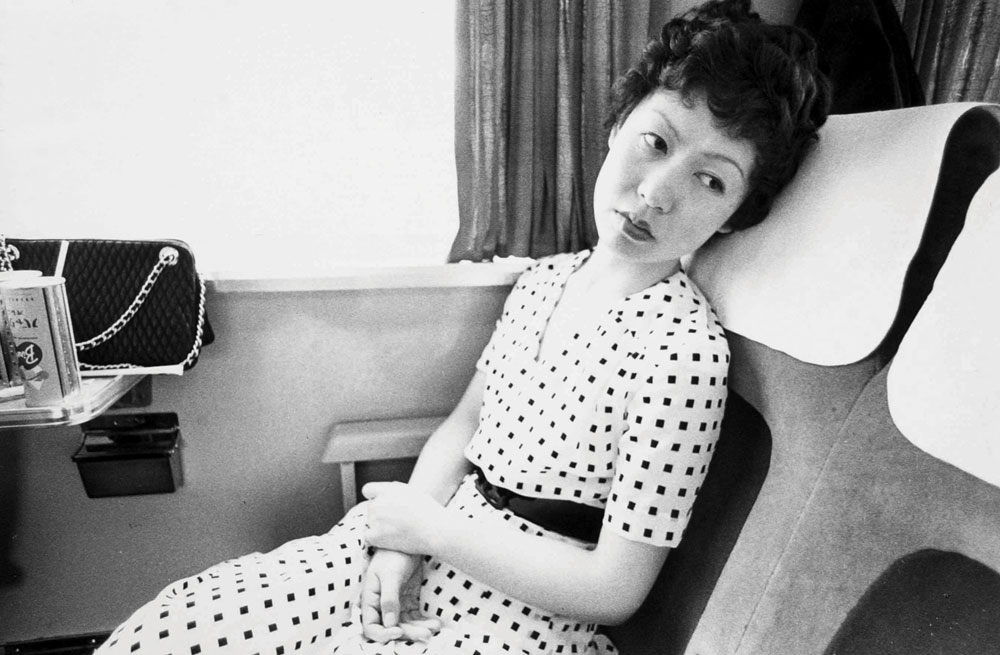

PHOTO:Nobuyoshi Araki -Impossible Love / Vintage Photographs

Nobuyoshi Araki worked in advertising after completing his studies in photography and film at Chiba University in Tokyo, devoting himself exclusively to photography as of the mid-1960s. His oeuvre spans erotic portraits of women, artificial still-lifes, photographs of plants, documentary-style depictions of everyday life, and architectural photography but also very personal, diaristic photographs of himself and his deceased wife Yoko.

Nobuyoshi Araki worked in advertising after completing his studies in photography and film at Chiba University in Tokyo, devoting himself exclusively to photography as of the mid-1960s. His oeuvre spans erotic portraits of women, artificial still-lifes, photographs of plants, documentary-style depictions of everyday life, and architectural photography but also very personal, diaristic photographs of himself and his deceased wife Yoko.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: C/O Berlin Foundation

The exhibition “Nobuyoshi Araki. Impossible Love-Vintage Photographs” at CO Berlin combines Araki’s Tokyo series from his early works with a selection of his recent Polaroid collages and newly developed slide shows – all of them exploring the contradictions between anonymity and intimacy, the public and private sphere, reality and dream. Araki’s extreme closeness and intimacy with the subjects and the situations depicted are unique and revolutionary to this day. In contrast to classic photojournalism, which looks into an unfamiliar world from the outside, Araki not only is part of his subjects’ lives but also plays a central role in his own photographs, thus transcending voyeurism. He navigates the tense relationship between classical visual composition and his chosen visual themes with a direct, intense visual language, creating works that are in equal parts moving and unsettling and that set him apart from virtually all of his peers. His work concentrates on a sexuality that is lived out in complete openness. In depicting this, the artist never denounces or accuses, but instead leaves all inter-pretation up to the viewer. Together with Nan Goldin and Larry Clark and Ukrainian Boris Mikhailow, Araki is considered one of the pioneers of intimate, subjective photography. Araki entered Chiba University in 1959, majoring in photography and film. The regimented and technical nature of the program, then situated in the engineering department, was unappealing to the nonconforming Araki. The film he turned in as his final project, however “Children in Apartment Blocks” (1963) served as the germ for one of his earliest photographic series, for which he received an award from Taiyo magazine the following year. “Satchin” (1964) focuses on schoolchildren in the Shitamachi neighborhood of Tokyo, which remained largely unchanged amid the flurry of rapid urban transformation leading up to the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. After graduation, Araki took a job as a commercial photographer for the advertising firm Dentsu. While he found the work frustratingly dull, he made good use of Dentsu’s well-stocked facilities to pursue photography on his own time, going so far as to illicitly use the company’s photocopier to produce an early photobook. Two events pivotal to Araki’s life and work took place in the late 1960s: his father died in 1967, and he met his future wife, Yoko Aoki, then working as a typist at Dentsu, the following year. Death and love would become two of the principal driving forces behind Araki’s profoundly human photography, and Yoko would become Araki’s most frequent photographic subject. The couple wed in 1971 and embarked on a honeymoon, which Araki extensively photographed. With its narrative style, personal tone, and vernacular aesthetic, the resulting volume “Sentimental Journey” (1971) is regarded as one of the most important Japanese photobooks of the 20th Century. Araki’s growing success as a photographer allowed him to leave Dentsu to focus solely on his artistic career in 1972. Araki has referred to his wide-ranging and eclectic work as “I-photography” after the “I-novel”, a Japanese confessional literary genre often written in the first person. His unwavering concentration on his own life and experiences pushed against the dominant documentary photographic aesthetic, epitomized by such figures as Hiroshi Hamaya, as well as the are, bure, boke (grainy, blurry, and out-of-focus) aesthetic of the Provoke movement, prevalent in Japanese Avant-Garde photography beginning in the late 1960s. Araki tackled these approaches head-on in his series “Pseudo-Reportage”. The related photobook, published in 1980, pairs these quasi-documentary pictures with misleading captions, underscoring the problematic nature of photographic veracity. After Yoko passed away, in 1990, Araki began a host of new projects, even using his own diagnosis with prostate cancer in 2008 as a jumping-off point to explore the diminishing status of analog photography.

Info: Curator: Felix Hoffmann, C/O Berlin Foundation, Amerika Haus, Hardenbergstrasse 22–24, Berlin, Duration: 8/12/18-383/19, Days & Hours: Daily 11:00-18:00, www.co-berlin.org