ART-PRESENTATION: Tetsugo Hyakutake-Postwar Conditions

Tetsugo Hyakutake works with contemporary issues in relation to their historical contexts. Through his artwork, he creates what he calls his own “truth” shaped by his personal experiences and influences. These “truths” are based on individual beliefs, identities, and relative perspectives rather than facts. Hyakutake’s work attempts to portray one version of the truth, all the while allowing the viewers’ own interpretations.

Tetsugo Hyakutake works with contemporary issues in relation to their historical contexts. Through his artwork, he creates what he calls his own “truth” shaped by his personal experiences and influences. These “truths” are based on individual beliefs, identities, and relative perspectives rather than facts. Hyakutake’s work attempts to portray one version of the truth, all the while allowing the viewers’ own interpretations.

By Dimitris Lempesis

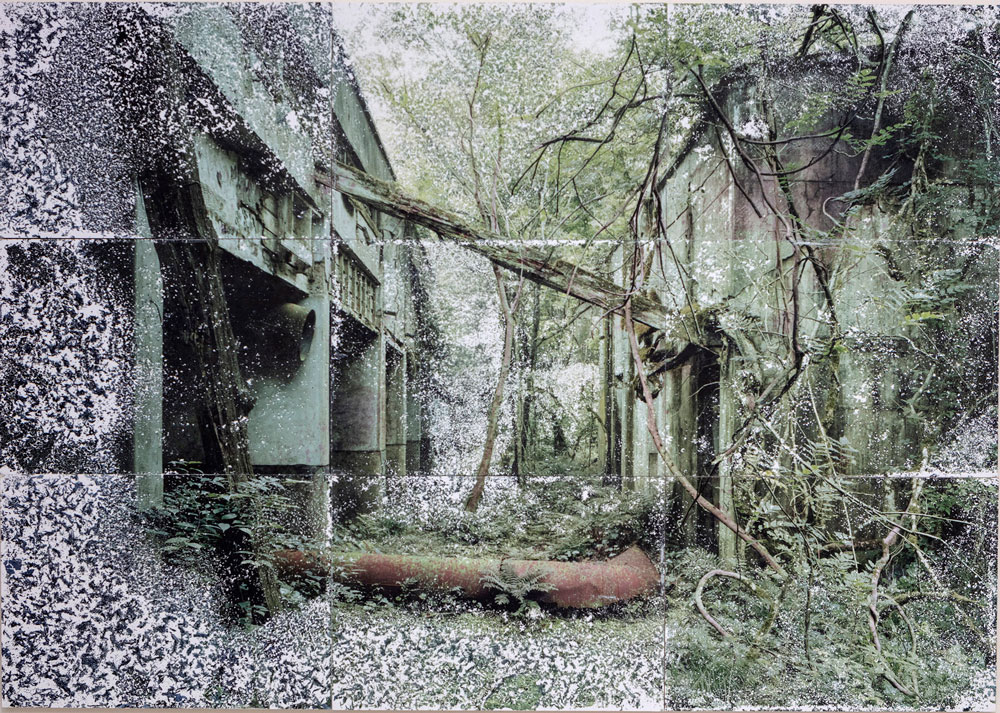

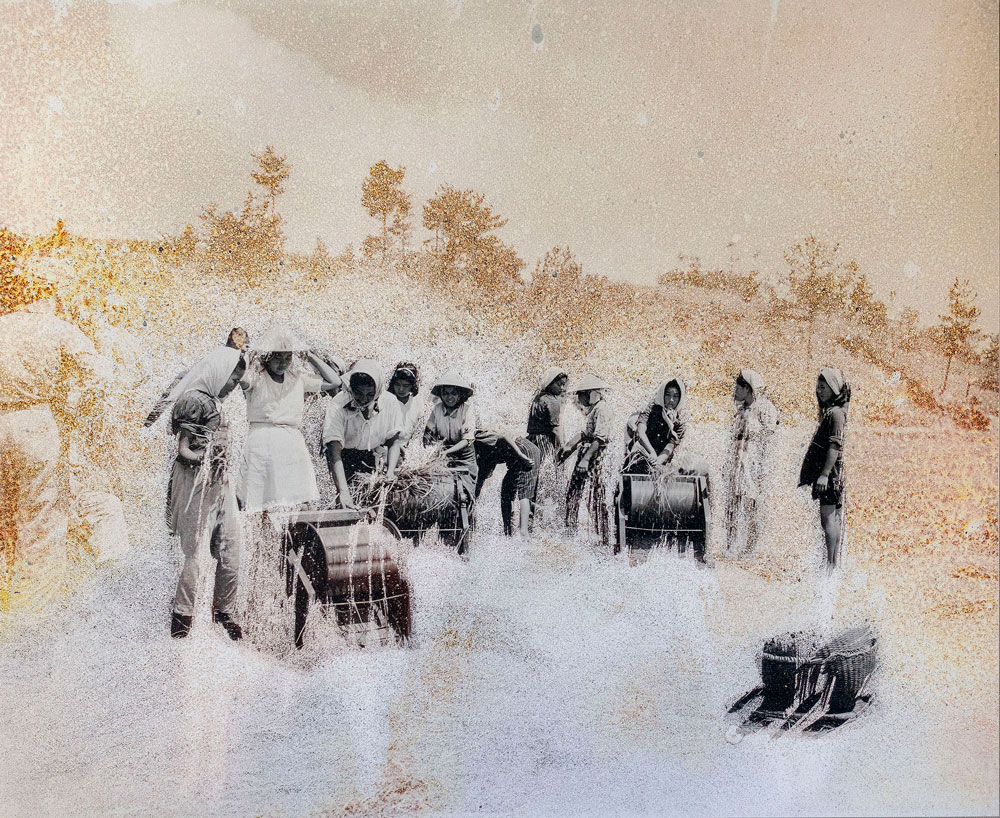

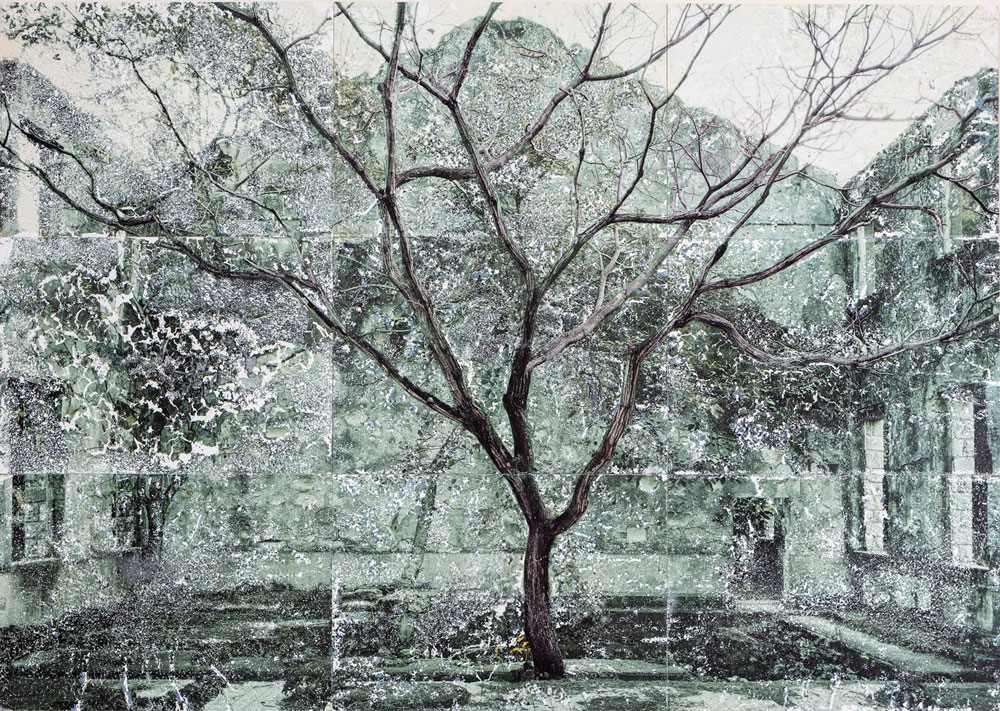

Photo: Camera Austria Archive

In his solo exhibition, “Postwar Conditions”, Tetsugo Hyakutake analyzes moments of Japan’s history since World War II and how they have affected current identity formations within the country, which, for many decades has been under the influence of the United States and, for some, still is. The artist seeks to pursue a past that relates to issues of colonization, war, and other decisive historical events that reflect on current issues of subjectivity in Japanese culture and the relationship between past and pres-ent, individual and collective memory and history. Hyakutake juxtaposes archival material with his own photographs and negotiates various levels of temporality within the photographic dispositive. He often applies a special technique by treating photographs with chlorine to make them appear like historical documents and thus creates an ontological leap between different realities, raising the question of how Japanese identity and thought have come into being. With the economic boom culminating in the 1980s, which was supposed to make up for losing the war, and which stagnated in the “Lost Decade” of the 1990s, Hyakutake’s works raise the question of how the international positioning of Japan has been subject to critical scrutiny and how the personal is put to the fore via an introspection of the dialectics between self-determination and the perception through the eyes of the Other, that is, a Westernized gaze. Belonging to the generation that has come of age in the “Lost Decade” of the 1990s, Hyakutake found himself trying to understand what it means to be Japanese today and how the Japanese subject is reflected upon within and outside of the country. Hyakutake’s reflections on contemporary Japan start with the developments following World War II. The artist is particularly drawn to the controversial debate concerning the responsibility of Emperor Hirohito, now called Emperor Shōwa, for the wartime atrocities committed by Japanese forces. The media hardly covered the topic of his leadership and responsibility during the war, which was generally considered taboo despite the fact that he had full power over the Japanese military according to the imperial constitution of Japan. He was the one who finally decided to end the war. Hyakutakealso focuses on General Douglas MacArthur, who oversaw the US occupation of Japan from 1945 to 1951 and the ensuing political, economic, and social changes. A three-channel video animation shows Japan’s surrendering Emperor Hirohito and General Mac-Arthur, as well as an image of the artist’s granduncle, who died in the Philippines, which Japan had invaded under MacArthur’s rule. The image was taken from a family photo depicting him shortly before he left for the war. One manipulated photo depicts two boys in Iwo Jima whose original photo negative was supposedly taken by American soldiers after 1945 and which was acquired by the artist at an auction; likewise the photo of women in Okinawa at that time, who are surrounded by American soldiers. Moreover, Hyakutake explores Japanese sites where preparations for war were already underway before World War II. He researched and visited such sites and then manipulated his own photographs accordingly. These sites include a torpedo test fire facility in a small port town in Nagasaki, a navy ammunitions arsenal as part of the Maizuru shipyard in Kyoto Prefecture, the Shime coal mine near Fukuoka, and poison gas storages erected in line with the Imperial Japanese Army’s Institute of Science and Technology’s secret program to develop chemical weapons, which was already launched in 1929. His technique involves bleaching photographs, which makes them look faded, cracked, and fragmented. These damaged photographs are representations of Hyakutake’s concern that the memory of the individuals suffering from misfortune might fade and fall into oblivion. The blurry surface quality creates an illusionary effect that asks questions about the authenticity of the image. At the same time, the artist frees the image from its factual qualities and turns the gaze to a different, volatile reality. Early moments of industrialization can be traced in photographs of bridges, such as the Yalu River Bridge, a half-destroyed railroad bridge over the Yalu River between the Chinese city of Dandong and the North Korean city of Sinuiju built by Imperial Japan in 1911. A contemporary approach would be the expressway bridge in Nihonbashi in the center of Tokyo, which translates into as “Japan Bridge”. Formerly a wooden bridge, Nihonbashi was reconstructed with stone in 1911. The expressway was built along with during the same period as the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and facilitated the city’s huge growth in post-industrial times. By combining these images, the artist poses questions as to how Japan’s force has been recognized outside of its geographical territory and especially within a Westernized hemisphere, which is likewise self-critical and “never content with what it is recognized as by others”. His works try to contribute to a history that has been disrupted by the same power it has nested upon, culling images from archives whose relevance has been fading in the wake of the country’s excelling in economic grandeur and at the same time overcoming failure as a non-existent phenomenon in everyday Japanese culture and thought.

Info: Camera Austria, Lendkai 1, Graz, Duration: 7/12/18-7/2/19, Days & Hours: Tue-Sun 10:00-17:00, https://camera-austria.at