ART-PRESENTATION: Anna Eva Bergman

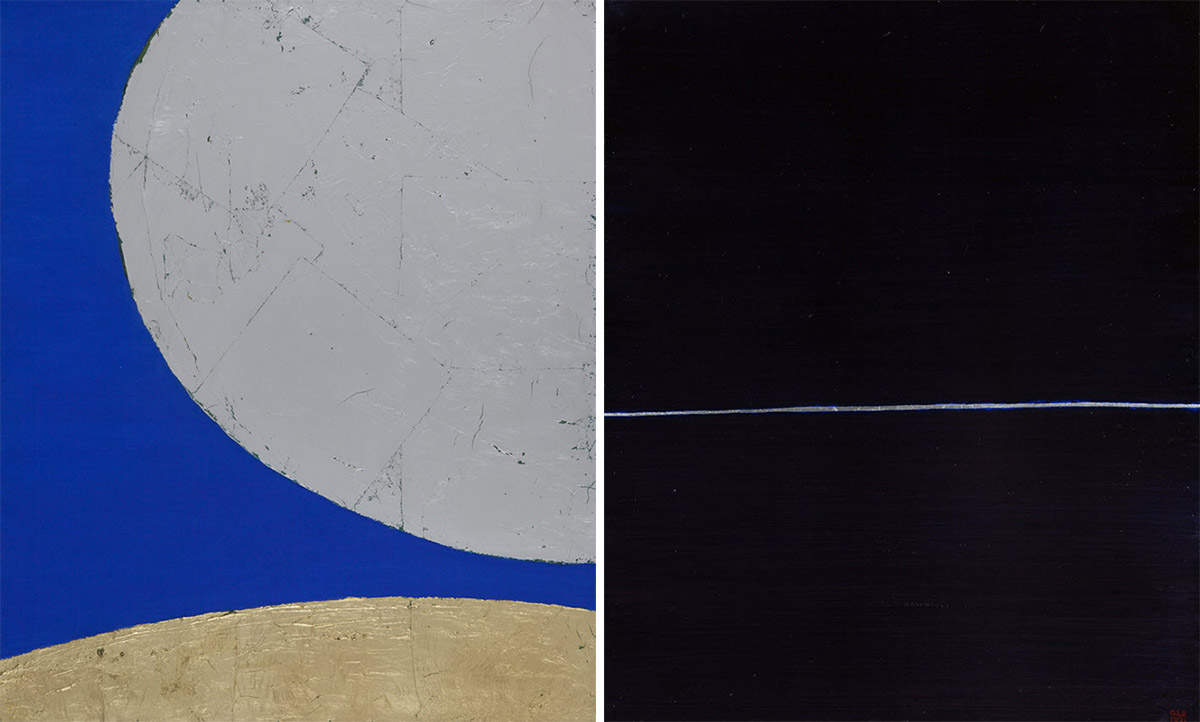

Anna-Eva Bergman is regarded as one of the best Norwegian painters of the 20th Century, she was long overshadowed by her husband, the painter Hans Hartung. She combines the experience of the Nordic landscape and light to form abstract pictures with an original design vocabulary. The use of materials such as gold and/or silver leaf combined with that of painting and a commitment to the symbolic reveal a metaphysical concept of the landscape and puts it out of step with the major aesthetic challenges of the 20th Century.

Anna-Eva Bergman is regarded as one of the best Norwegian painters of the 20th Century, she was long overshadowed by her husband, the painter Hans Hartung. She combines the experience of the Nordic landscape and light to form abstract pictures with an original design vocabulary. The use of materials such as gold and/or silver leaf combined with that of painting and a commitment to the symbolic reveal a metaphysical concept of the landscape and puts it out of step with the major aesthetic challenges of the 20th Century.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Bombas Gens Centre d’Art Archive

The exhibition “From North to South, Rhythms” presents a selection of works by Anna-Eva Bergman, made from 1962 to 1971, coinciding with a series of trips she took to Spain and Norway. These journeys led to a permanent dialogue between North and Zouth in her landscapes, which are formally similar but offer a very different depiction of light. Born in Norway, but already working mostly in Paris and Antibes, in 1962 the artist visited Carboneras, in Almería. This journey would become decisive, as it is where she started to make her first horizons, a motif she retook later on when she came in contact again with the Norwegian landscapes. Stones, another of Bergman’s motifs, had originated after a trip she took to Norway in 1951, and this motif then found continuity when she travelled through the interior of the Iberian Peninsula, as evidenced by her series “Stones of Castile” (1970). The artist made many photographs during these travels, which she used as a trace, as a memory or memento. Therefore the landscapes were portrayed from a great distance between the painting and the per-ception, which changed with the passing of time. Along with stones and horizons. The pictorial construction tends to transcend the surface through the immediacy of the form, the use of large formats or the superposition of layers of different materials, such as metal foil, gold leaf and copper. These materials cover a previous thick layer of paint or, in some cases, the artist used varnish to change its appearance and give greater density to the paint. Resorting to those materials, together with the use of shapes, lines and colors, is what Bergman considered the “rhythm”, a structural element essential for painting. The layers intermix and modify the perception of color depending on the light. This technique provides relief and a drawing which is only visible with the luminous reflections of the met-al, creating a physical experience of the painting which translates into the finite the feeling of infiniteness. Her intense relationship with the landscape ultimately focuses on the elements which make up and animate nature (air, fire, water, earth) in an attempt to trap immateriality in the materiality of the work. This tendency towards opening up the pictorial space places the artist within the line of landscape representation characteristic of North American painters such as Mark Rothko, with whom Bergman was very familiar, and also within the tradition of northern European Romanticism. Romantic painters like Caspar David Friedrich or J.M.W. Turner expressed experiences such as the infinite or the divine through landscape as the best expression of “the sublime”. Following artistic studies in Oslo and in Vienna, Anna-Eva Bergman came to Paris in 1929 where she followed for some time André Lhote’s courses. She met Hans Hartung whom she married only a few months after their meeting. At the end of the 1920s and during the 1930s her work was made up essentially of drawings, watercolors and caricatures at the same time naïve, full of humor and a social or political critique sometimes fierce in the run-up to the war. She separated a first time from Hans Hartung in 1937, and then returned to live in Norway. The war years were to be a period of intellectual training for Bergman. She studied philosophy, literature and architectural laws, all the while carrying out work as an illustrator for publishing and press. She took up painting again at the beginning of 1946 and towards the end of the 1940s carried out a large number of abstract works. Then, very quickly, she found the plastic language that is significant of her work, profoundly inspired by her Norwegian culture and her observation of the vast Nordic landscapes that she discovered while travelling to the north of Norway and to the Lofoten isles, on the frontier of Russia. In 1952 she rejoined Hartung in Paris whom she remarried in 1957. From 1952 to 1987, she explored a singular pursuit and managed to create modern icons, images of absence, more and more marked by a form of incarnate minimalism. The Galerie de France consecrated a first one-woman show to her work in 1958. The 1960s were to be those of development in her artistic career: exhibition in 1966 at the Kunstnernes Hus in Oslo; in 1967, at the Galleria Civica in Turin; in 1969, she represented Norway in the Sao Paulo Biennale. A retrospective in 1977-1978 at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris crowned her career however modest with regard to the uniqueness and the importance of the work.

Info: Curators: Nuria Enguita and Christine Lamothe, Bombas Gens Centre d’Art, Av. Burjassot 54, Valencia, Duration: 14/11/18-5/5/19, Days & Hours: Wed 16:00-20:00, Thu-Sun 11:00-14:00-16:00-20:00, www.bombasgens.com