ART CITIES:N.York-Agnes Martin/Navajo Blankets

By 1830, the price for a Navajo Chief’s Blanket was either 100 buffalo hides, 20 horses, 10 rifles, or 5 ounces of gold. Among high-ranking members of the Plains and Prairie tribes, including the Arapahoe, Assiniboine, Cheyenne, Comanche, Kiowa, Mandan, and Sioux, a Navajo chief’s blanket was a form of currency. Navajo blankets were expensive, they were the most expensive garments in the world, but they held their value. On 19/6/2012, Donald Ellis, owner of the Donald Ellis Gallery in New York City paid $1,800,000 for a Navajo chief’s blanket.

By 1830, the price for a Navajo Chief’s Blanket was either 100 buffalo hides, 20 horses, 10 rifles, or 5 ounces of gold. Among high-ranking members of the Plains and Prairie tribes, including the Arapahoe, Assiniboine, Cheyenne, Comanche, Kiowa, Mandan, and Sioux, a Navajo chief’s blanket was a form of currency. Navajo blankets were expensive, they were the most expensive garments in the world, but they held their value. On 19/6/2012, Donald Ellis, owner of the Donald Ellis Gallery in New York City paid $1,800,000 for a Navajo chief’s blanket.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Pace Gallery Archive

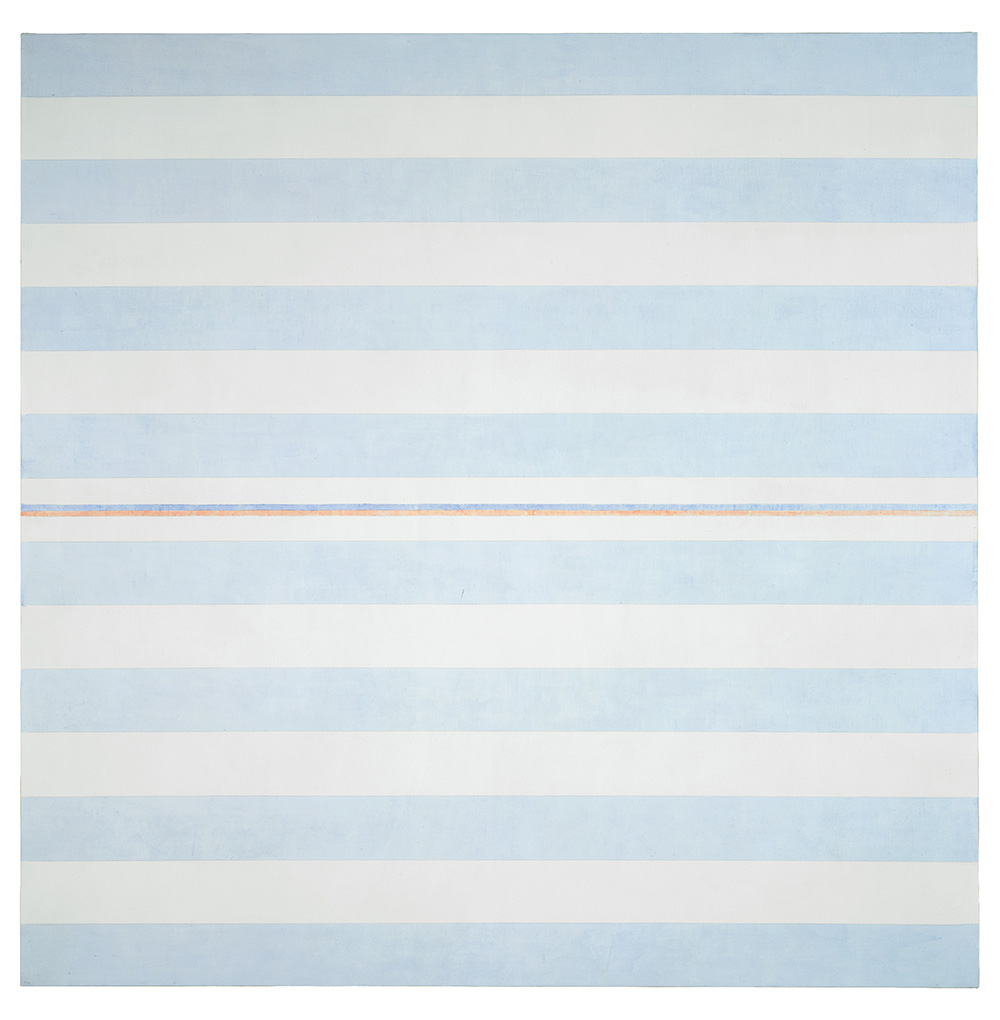

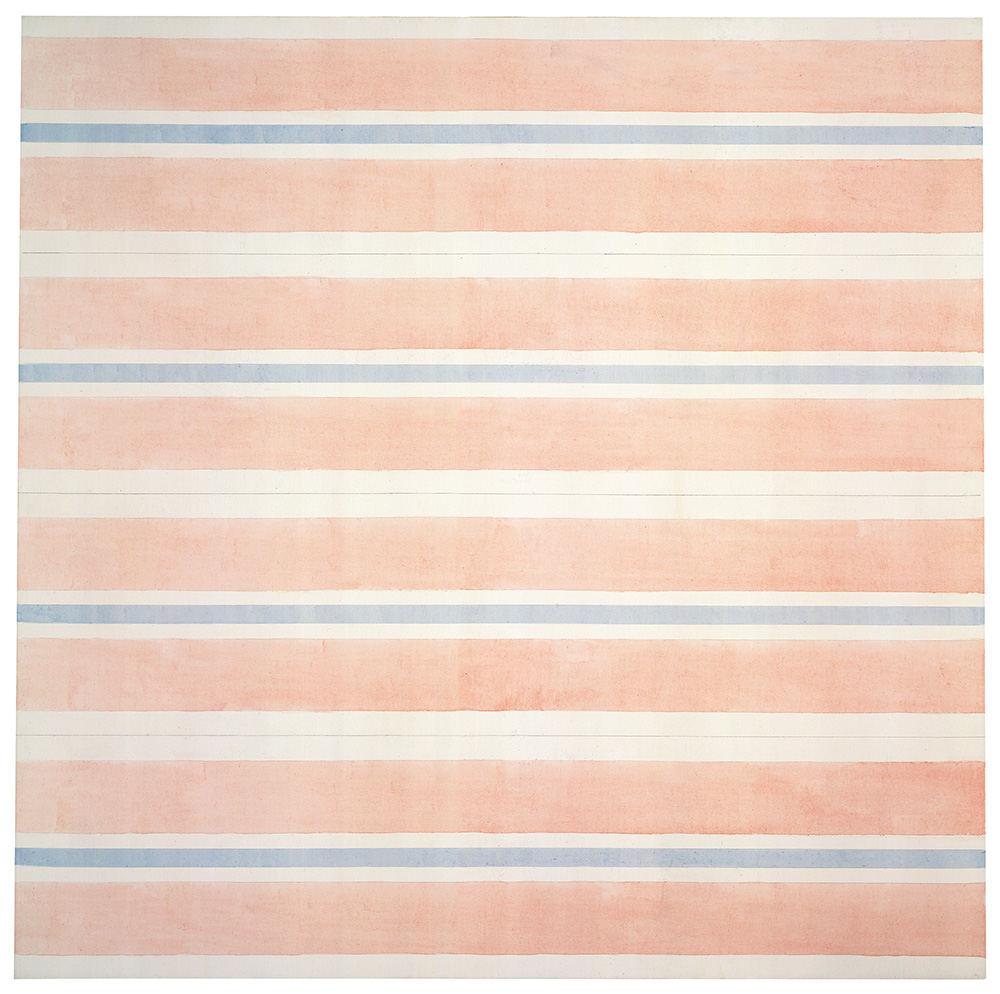

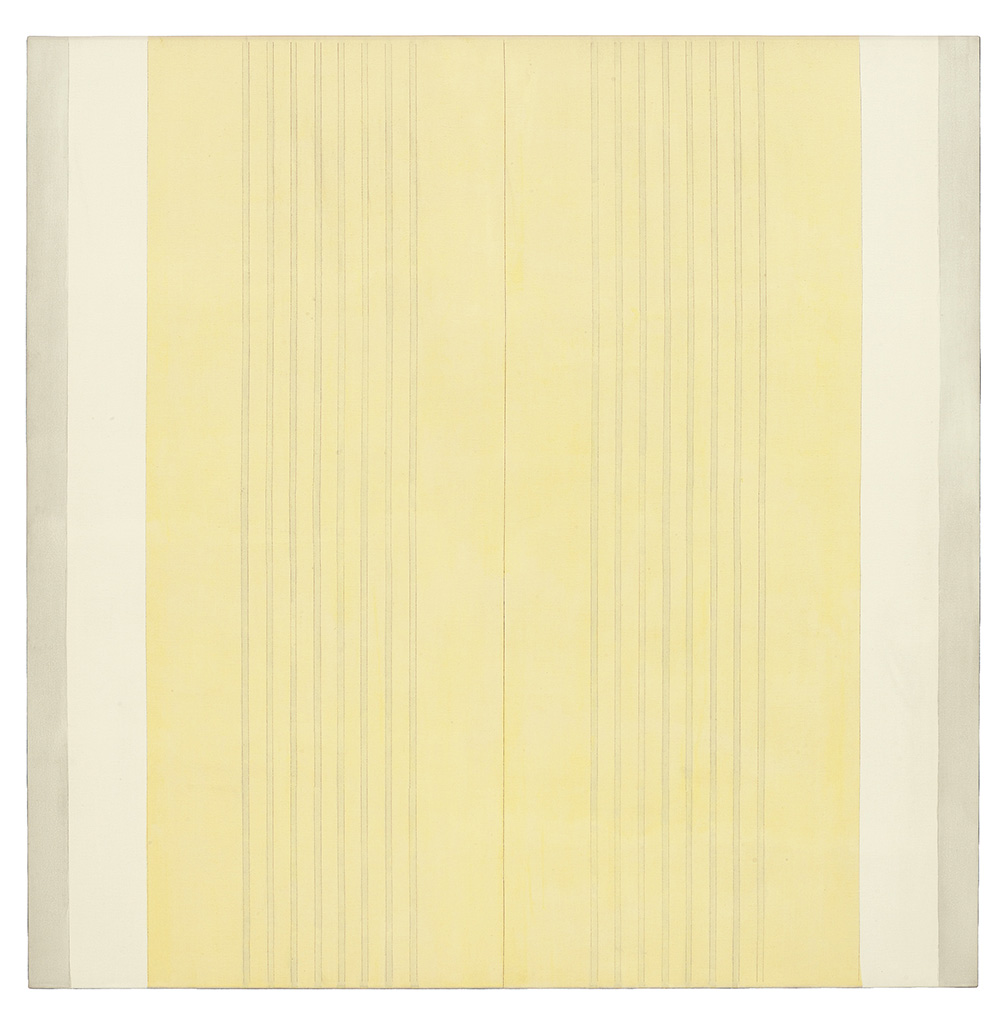

The first exhibition of its kind, “Agnes Martin/Navajo Blankets”, features a selection of paintings by Agnes Martin throughout career in dialogue with handwoven wearing textiles by Navajo (Diné) weavers from the 19th Century, the exhibition illuminate parallels between these exquisitely-crafted and transcendent bodies of work. While the Navajo language has no singular term for “art,” the powerfully descriptive word “hózhó” refers to harmony and balance in both aesthetic and intrinsic forms, a state of being where the natural and the supernatural can coexist. The Navajo believe that their women learned the art of spinning and upright loom weaving from Na’ashjéii Asdzáá, (Spider Woman). While Spider Woman is regarded as a deity, and as a key figure in the Navajo creation myth, she is also revered as the first Navajo weaver, and as a source of hozho. During the mid- to late 18th Century, Navajo women began weaving a plain-woven, woolen blanket that was also woven wider than long. The blanket’s only designs were horizontal brown and white stripes overlaid with horizontal thin blue stripes. The illusion of thin horizontal blue stripes lying on top of the thicker horizontal brown stripes was a Navajo innovation. Navajo chief’s blankets fall into three phases and variants: First phases have horizontally striped fields with no foreground designs date from 1860 or earlier, first phases with red stripes are known either as “Bayeta First Phases” or, less often, as “Navajo Style First Phases”. In about 1850, Navajo weavers began adding red rectangles to their blanket designs, which cultural historians use as a marker for second-phase chief’s blankets, which were made until about 1880. They always have 12 rectangles, grouped in twos. In the third phase, they have to nine diamonds and half-diamonds. As these design elements were added, they grew larger, becoming more centerpieces of the blankets than embellishments. During the third phase, Navajo weavers also added elements inside the diamonds, including, zigzags, crosses, thin lines, stacked elements, and triangles. At the beginning of the second phase, the weavers had also started expanding their color palette, adding yellow and green accents. But one of the colors the Navajo weavers coveted most was the red from the prized bayeta cloth made in England and later, in Spain and Mexico. They would unravel the cloths and then weave the material into rectangles on their blankets. The bayeta, occasionally used in first-phase blankets, became a color and cloth that Navajo weavers used prominently in the second phase. While Agnes Martin took no direct inspiration from the aesthetics of Navajo weaving in her approach to painting, she spent much of her life in New Mexico, and the region’s cultural history and artistic production suffused her experience. Using a limited color palette and a geometric vocabulary, her works are inscribed with lines, grids, or simple shapes that hover over subtle grounds of color. Maximizing the strength of pure abstraction, she explored space, metaphysics, and internal emotional states throughout her practice. As exemplified by Martin’s paintings on view in the exhibition, a profound reverence for the transcendent power of balance thrives within her work. By placing these two bodies of work in dialogue with one another for the first time, the exhibition encourages the discovery of their compelling resonances and invites new appreciation for their respective emotional impact and contributions to our shared visual culture.

Info: Pace Gallery, 537 West 24th Street, New York, Duration: 14/11-21/12/18, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 10:00-18:00, www.pacegallery.com