TRACES: Rosemarie Trockel

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Rosemarie Trockel (13/11/1952- ), which is one of the most multi-faceted and idiosyncratic artists of our time. Her breakthrough came in the 1980s, and ever since she has been critically examining art, the structures of society, and gender roles with analytical acuity and humor and with a sensuality that is all her own. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Rosemarie Trockel (13/11/1952- ), which is one of the most multi-faceted and idiosyncratic artists of our time. Her breakthrough came in the 1980s, and ever since she has been critically examining art, the structures of society, and gender roles with analytical acuity and humor and with a sensuality that is all her own. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Efi Michalaou

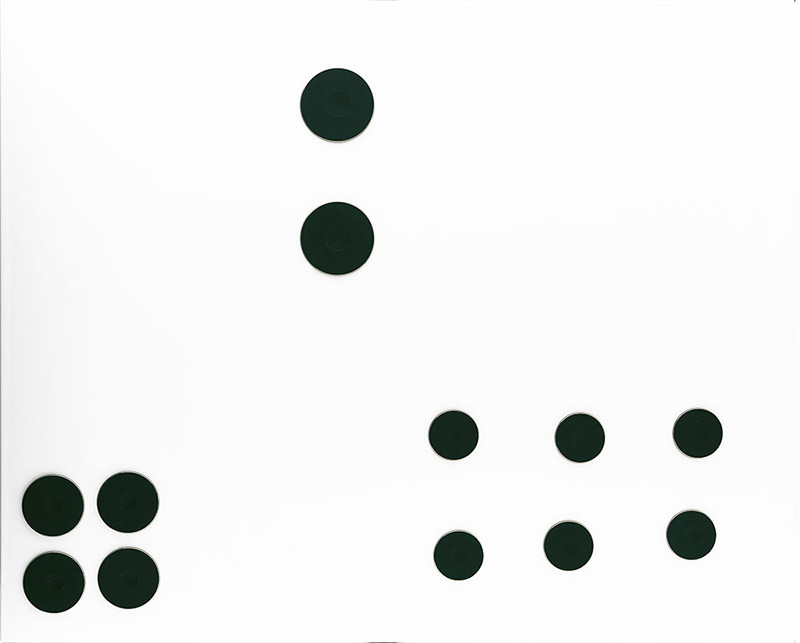

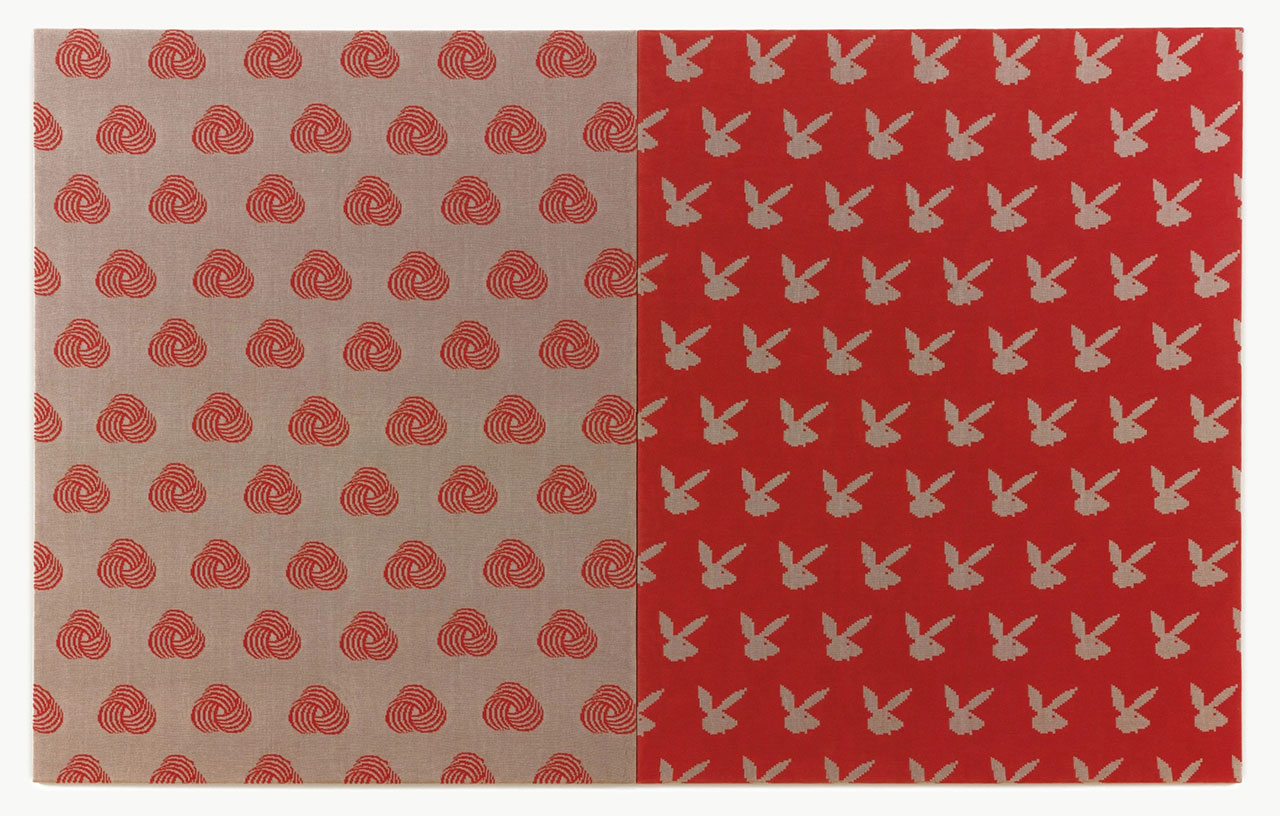

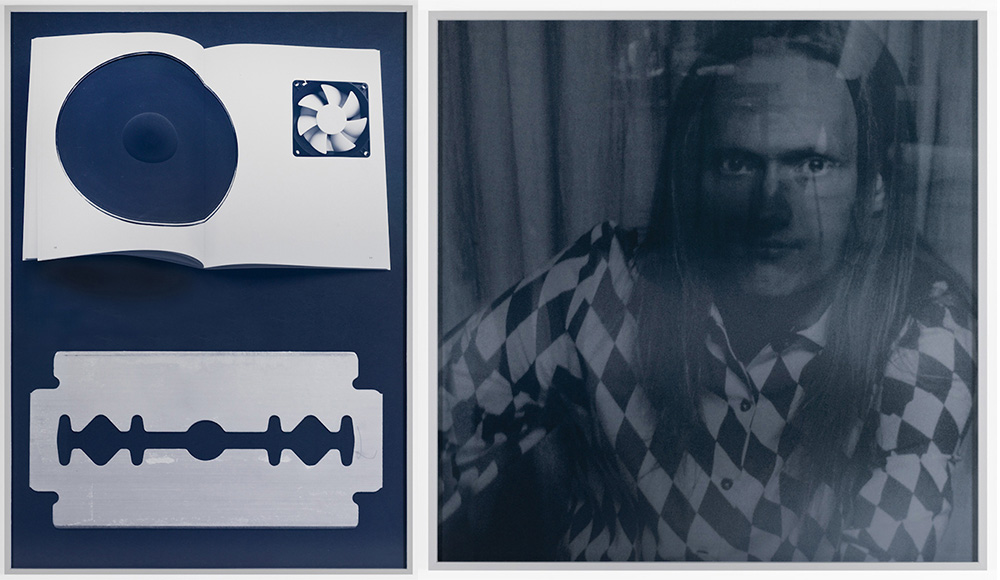

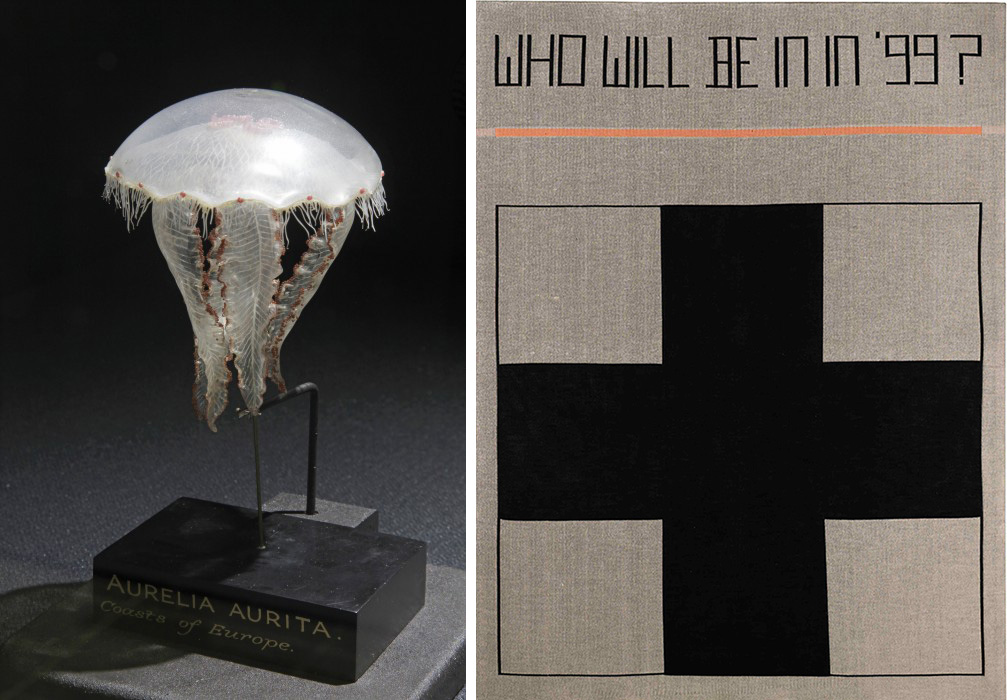

Rosemarie Trockel was born in Schwerte, Germany on 13/11/1952. She studied in the Werkkunstschule in Cologne until 1978. During her school days, Trockel has already shown an undeniable interest is the grotesque and the unusual and majority of her early artworks were influenced by the later forms of Surrealism. Another major influence when it comes to Trockel’s art study was Joseph Beuys. Trockel is known to experiment with many mediums, such as film, video, ceramics, drawings, and collages, which emphasizes the strength of Trockel’s talent. In addition to her works in film, ceramics, and drawings, a lot of Trockel’s pieces represent innovative sculptures done in an array of different materials. In the early 1980s, Trockel became an active exhibitor and her first solo shows were held at Monika Sprüth Gallery in Cologne, which was famous for showcasing only female artists. Since the German art scene at the time was dominated by male artists such as like Joseph Beuys and Gerhard Richter, Trockel’s presence was really refreshing and daring at the same time. Trockel’s oeuvre is diverse in themes and mediums, which include works on paper, “Knitted paintings” and sculptures. Though it is difficult to associate a particular style with her work, several concurrent themes can be identified, such as the female’s role in society, trademarks and symbols as social signifiers and decorations and finally, her fascination with ethnographic and scientific studies, often expressed through her sculptures. Begun in 1984, and choosing wool and knitting, a material and technique traditionally associated with the female domestic realm and craft, Trockel explores the negative connotations of these “inferior materials and skills”. Distinguishing her practice from traditional craft, Trockel made blueprints for her designs and had them produced by a technician using computerised machinery. By mechanically producing the knitted patterns, she questions whether the cliché of women’s art relates solely to the choice of materials or whether it is also influenced by the treatment of these materials. “I wanted to know what causes a given kind of work to be regarded by women as embarrassing, both in the past and in the present: whether this has to do with the way the material is handled or whether it really lies in the material itself”. Incorporating serial patterns and identifiable logos, the knitted paintings highlight the manipulation of visual culture through signs and logos. “In Made in Western Germany”, one of Trockel’s most recognisable knitted pictures, she makes reference not only to her German background but also to the commodification of art in a consumerist society. Repeating the phrase in a linear composition across the large-scale knitted plane, Trockel highlights this culturally loaded motif and its industrial production method, as well as engaging questions of originality, with notable reference to Warhol’s Pop art aesthetic. Indeed, each of the works included in the exhibition demonstrate Trockel’s keen acknowledgment of art history, with further references to Minimal Art, the movement to first introduce industrial production techniques into art. In works such as “Untitled” (1992), from a series based on Hermann Rorschach’s ‘Ink blot’ constellations, Trockel presents her own interpretation of this subject explored most notably by Warhol for its blurring of abstraction and representation. Through her digitalisation of this free-form method of image production, Trockel challenges the chance patterning of the Rorschach tests and replaces the automatic qualities of this technique favoured by the Surrealists with a codified structure. In “Who Will Be In In ’99?” (1988) featuring a computer-rendered black geometric Trockel pokes subtle jest at the repeated citation of the 1960s male artists as provoking a radical reconsideration of the nature of painting. Subverting the embedded hierarchies and outdated gender politics through her combination of materials and methods, Trockel paves way for a revised way of looking and attributing value to artistic production. By contrast with Sigmar Polke, who challenged the conventions of “high art” through his use of cheap printed fabric as a support for his painting in place of canvas, in her knitted works, Trockel redefines the picture by designing her own support and turning it into a picture in its own right.

Rosemarie Trockel was born in Schwerte, Germany on 13/11/1952. She studied in the Werkkunstschule in Cologne until 1978. During her school days, Trockel has already shown an undeniable interest is the grotesque and the unusual and majority of her early artworks were influenced by the later forms of Surrealism. Another major influence when it comes to Trockel’s art study was Joseph Beuys. Trockel is known to experiment with many mediums, such as film, video, ceramics, drawings, and collages, which emphasizes the strength of Trockel’s talent. In addition to her works in film, ceramics, and drawings, a lot of Trockel’s pieces represent innovative sculptures done in an array of different materials. In the early 1980s, Trockel became an active exhibitor and her first solo shows were held at Monika Sprüth Gallery in Cologne, which was famous for showcasing only female artists. Since the German art scene at the time was dominated by male artists such as like Joseph Beuys and Gerhard Richter, Trockel’s presence was really refreshing and daring at the same time. Trockel’s oeuvre is diverse in themes and mediums, which include works on paper, “Knitted paintings” and sculptures. Though it is difficult to associate a particular style with her work, several concurrent themes can be identified, such as the female’s role in society, trademarks and symbols as social signifiers and decorations and finally, her fascination with ethnographic and scientific studies, often expressed through her sculptures. Begun in 1984, and choosing wool and knitting, a material and technique traditionally associated with the female domestic realm and craft, Trockel explores the negative connotations of these “inferior materials and skills”. Distinguishing her practice from traditional craft, Trockel made blueprints for her designs and had them produced by a technician using computerised machinery. By mechanically producing the knitted patterns, she questions whether the cliché of women’s art relates solely to the choice of materials or whether it is also influenced by the treatment of these materials. “I wanted to know what causes a given kind of work to be regarded by women as embarrassing, both in the past and in the present: whether this has to do with the way the material is handled or whether it really lies in the material itself”. Incorporating serial patterns and identifiable logos, the knitted paintings highlight the manipulation of visual culture through signs and logos. “In Made in Western Germany”, one of Trockel’s most recognisable knitted pictures, she makes reference not only to her German background but also to the commodification of art in a consumerist society. Repeating the phrase in a linear composition across the large-scale knitted plane, Trockel highlights this culturally loaded motif and its industrial production method, as well as engaging questions of originality, with notable reference to Warhol’s Pop art aesthetic. Indeed, each of the works included in the exhibition demonstrate Trockel’s keen acknowledgment of art history, with further references to Minimal Art, the movement to first introduce industrial production techniques into art. In works such as “Untitled” (1992), from a series based on Hermann Rorschach’s ‘Ink blot’ constellations, Trockel presents her own interpretation of this subject explored most notably by Warhol for its blurring of abstraction and representation. Through her digitalisation of this free-form method of image production, Trockel challenges the chance patterning of the Rorschach tests and replaces the automatic qualities of this technique favoured by the Surrealists with a codified structure. In “Who Will Be In In ’99?” (1988) featuring a computer-rendered black geometric Trockel pokes subtle jest at the repeated citation of the 1960s male artists as provoking a radical reconsideration of the nature of painting. Subverting the embedded hierarchies and outdated gender politics through her combination of materials and methods, Trockel paves way for a revised way of looking and attributing value to artistic production. By contrast with Sigmar Polke, who challenged the conventions of “high art” through his use of cheap printed fabric as a support for his painting in place of canvas, in her knitted works, Trockel redefines the picture by designing her own support and turning it into a picture in its own right.