ART CITIES:N.York-Charles White

Charles White powerfully interpreted African American history, culture, and lives over the course of his four-decade career. A superbly gifted draftsman and printmaker as well as a talented mural and easel painter, he developed a distinctive and labor-intensive approach to art making and remained committed to a representational style at a time when the art world increasingly favored abstraction.

Charles White powerfully interpreted African American history, culture, and lives over the course of his four-decade career. A superbly gifted draftsman and printmaker as well as a talented mural and easel painter, he developed a distinctive and labor-intensive approach to art making and remained committed to a representational style at a time when the art world increasingly favored abstraction.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo MoMA Archive

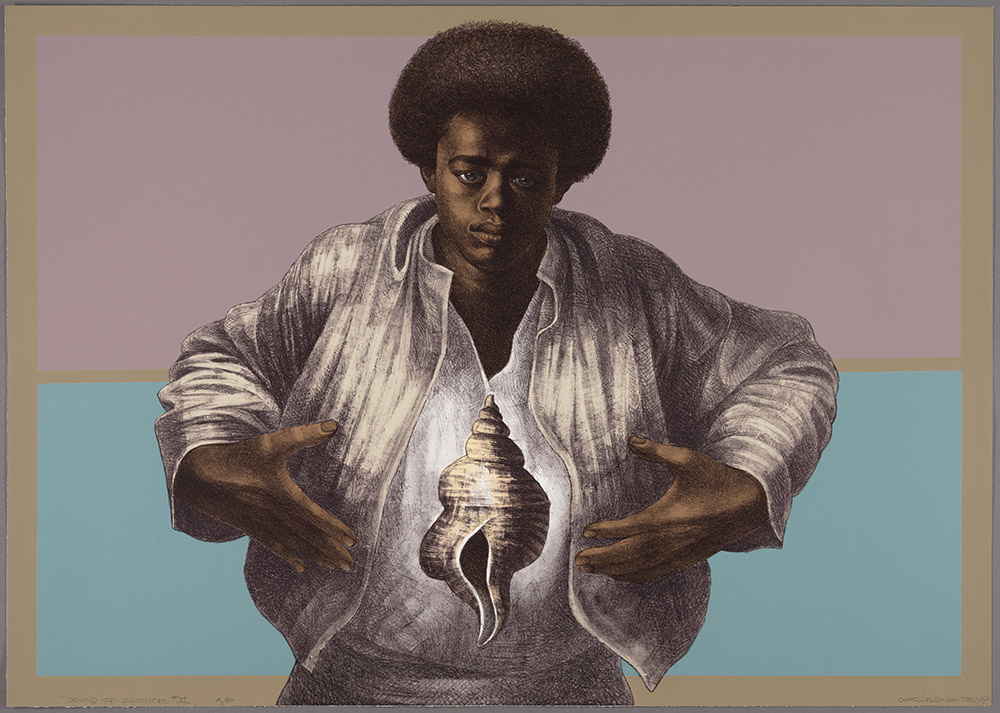

Charles White’s work magnified the power of the black figure through scale and form, communicating universal human themes while also focusing attention on the lives of African Americans and the struggle for equality. Organized chronologically, “Charles White: A Retrospective” charts the entirety of White’s career, illuminating his socially motivated responses to the tumultuous events and cultural episodes that defined 20th Century American history. The exhibition’s roughly 100 drawings, paintings, and prints, along with additional ephemera, attest to White’s continually developing body of work, and serve as a model for the active role art can play in contemporary society. The exhibition includes representative work from the three artistic centers in which White lived, created, and taught throughout his life: Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles. It begins with early paintings and murals that White made for the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in Depression-era Chicago, where he grew up. Shortly thereafter, between 1942 and 1956, White lived mainly in New York City, teaching drawing, exhibiting at the progressive ACA Gallery on 57th Street, and supporting the Committee for the Negro in the Arts in Harlem. A selection of White’s personal photographs, also on view in the exhibition, capture his life in New York, while the inclusion of his work for album covers, publications, film, and television emphasize his dedication to more accessible distribution outlets for his art. The presentation concludes with the inventive output from his last decades as an internationally established figure and influential teacher in Los Angeles during the 1960s and ’70s. A number of rarely exhibited key works from across White’s oeuvre are gathered for the first time, and are included exclusively in MoMA’s presentation of the exhibition. White’s first mural, “Five Great American Negroes” (1939), and the drawing “Native Son No. 2” (1942) are on loan from the Howard University Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. Two other seldom-seen masterpieces, “Mahalia” (1955) and “Folksinger (Voice of Jericho: Portrait of Harry Belafonte)” (1957), are on loan from the collection of Pamela and Harry Belafonte, the latter of whom was a close friend and collaborator of White’s. By the time Charles White graduated from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1938, he was already an active member of a multidisciplinary community of artists practicing on Chicago’s South Side. He began making paintings for the WPA Federal Art Project, a massive government relief measure that hired artists across all media, and helped found the South Side Community Art Center (SSCAC), a WPA-sponsored art center that provided formal art education and exhibition space for artists who were denied gallery representation elsewhere. White’s first mural, “Five Great American Negroes”, was created as part of a fundraiser for the SSCAC. A tableau of African American history, it depicts: activist Sojourner Truth, educator Booker T. Washington, abolitionist Frederick Douglass, scientist George Washington Carver, and musician Marian Anderson. The mural, intended for public display, also integrated public opinion in its composition: the five central figures were selected by the readers of the Chicago Defender, a major African American newspaper. White painted three other murals during the War Years; these large-scale, widely accessible paintings allowed his celebration of African American contributions to society, as well as his condemnation of the violence and oppression they faced, to reach broad and integrated audiences. The medium perfectly suited his lifelong goal of combatting what he referred to as “A plague of distortions, stereotyped and superficial caricatures of ‘uncles,’ ‘mammies,’ and ‘pickaninnies’” in popular visual culture. In Chicago, White’s circle of friends included visual artists, writers, and poets, all of whom shared a devotion to improving the lives of African Americans in the city. Their work provided ample source material for his earliest paintings and drawings, rendered in an expressive figurative style. For example, in “Native Son No. 2” White envisioned the main character of his friend Richard Wright’s seminal novel of the same title. White’s layered political statements of the 1940s and ’50s reflect on the intersectional discrimination against African Americans, women, laborers, and political radicals. During this time, he was commissioned by leftist and Marxist journals like the Daily Worker and New Masses (later Masses & Mainstream), where White was an editor, to illustrate current events; in his independent artistic practice he continued to link African American historical figures with contemporary political and social causes. Images such as “Our Land” (1951), which highlights the essential cultural and economic role African American women play in the United States, became vehicles for his pro-labor stance. In keeping with his commitment to making his work available to the largest possible audience, White contributed to many commercial and popular entertainment projects, including book illustrations, album covers, and commissions for television and film. In the 1950s, he produced drawings for Vanguard Records’ Jazz Showcase series album covers, and in 1965 was nominated for a Grammy Award for “Best Album Cover, Graphic Arts”. White was also a prolific photographer, and the photographs on view in the exhibition illustrate his life in New York, including images of family, friends, and fellow artists; documentation of political activism; and snapshots of his students at the New York Workshop School of Advertising and Editorial Art; among other subjects. While White did not consider his photographs part of his formal art practice, and they were never exhibited during his lifetime, many of them became visual references and source material for future drawings, paintings, and prints. Music, always an integral part of White’s life, grew increasingly central to his work in the 1950s. Throughout the decade, he took influential musicians as his subjects, creating canonical portraits of figures like Harry Belafonte, Mahalia Jackson, Paul Robeson, and Bessie Smith. “Folksinger (Voice of Jericho: Portrait of Harry Belafonte)” is one such example, depicting White’s collaborator and close friend during his time in New York. This drawing featured prominently in the 1959 television special Tonight with Belafonte, which also included White’s drawings in between changing musical acts. Powerful images from the 1960s exemplify White’s continued political activism and interest in social justice. The exhibition includes four drawings from the “J’Accuse” series, a group of 12 drawings executed between 1965 and 1966 that White retitled with this single moniker just before an exhibition at Heritage Gallery in Los Angeles. The new titles refer to French writer Émile Zola’s infamous indictment of his government’s anti-Semitism and political persecution; White’s adoption of the term applied this universal excoriation of injustice in contemporary race relations and the ongoing fight for civil rights. White began to teach at Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles in 1965, mentoring students such as Kerry James Marshall, David Hammons, and many others. In the last decade of his career, the artist also pioneered new visual and technical styles, including the development of a layered, multidimensional oil-wash drawing technique. He honed this practice in works from his “Wanted Poster” Series (1969–71), which were modeled after Civil War–era posters that sought the recapture of enslaved people who had escaped. White’s evolving interpretations of contemporary events throughout his career adapt to changing sociopolitical conditions and imperatives. His masterful navigation of four tumultuous decades of American history continues to serve as a model for socially conscious artists, activists, and thinkers today.

Info: Curators: Esther Adler and Sarah Kelly Oehler, The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), 11 West 53 Street, New York, Duration: 7/10/18-13/1/19, Days & Hours: Mon-Thu & Sat-Sun 10:30-17:30, Fri 10:30-20:00, www.moma.org

![Left: Charles White, Love Letter II, 1977, Color lithograph, 76.5 × 57 cm, The Art Institute of Chicago, Margaret Fisher Fund.], © The Charles White Archives/ © The Art Institute of Chicago. Right: Charles White, Paul Robeson (Study for Contribution of the Negro to Democracy in America), 1942-43, Carbon pencil over charcoal, with additions and corrections in white gouache, and border in carbon pencil, on cream drawing board, 63.2 × 48.4 cm, Princeton University Art Museum. Museum purchase, Kathleen Compton Sherrerd Fund for Acquisitions in American Art, © The Charles White Archives/ Art Resource-NY](http://www.dreamideamachine.com/web/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/047.jpg)