ART CITIES: Copenhagen-Danh Vo

Danh Vo’s artworks dissect the power structures, cultural forces, and private desires that shape our experience of the world. His work addresses themes of religion, colonialism, capitalism, and artistic authorship, but refracts these sweeping subjects through intimate personal narratives, what the artist calls “The tiny diasporas of a person’s life”.

Danh Vo’s artworks dissect the power structures, cultural forces, and private desires that shape our experience of the world. His work addresses themes of religion, colonialism, capitalism, and artistic authorship, but refracts these sweeping subjects through intimate personal narratives, what the artist calls “The tiny diasporas of a person’s life”.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: National Gallery of Denmark Archive

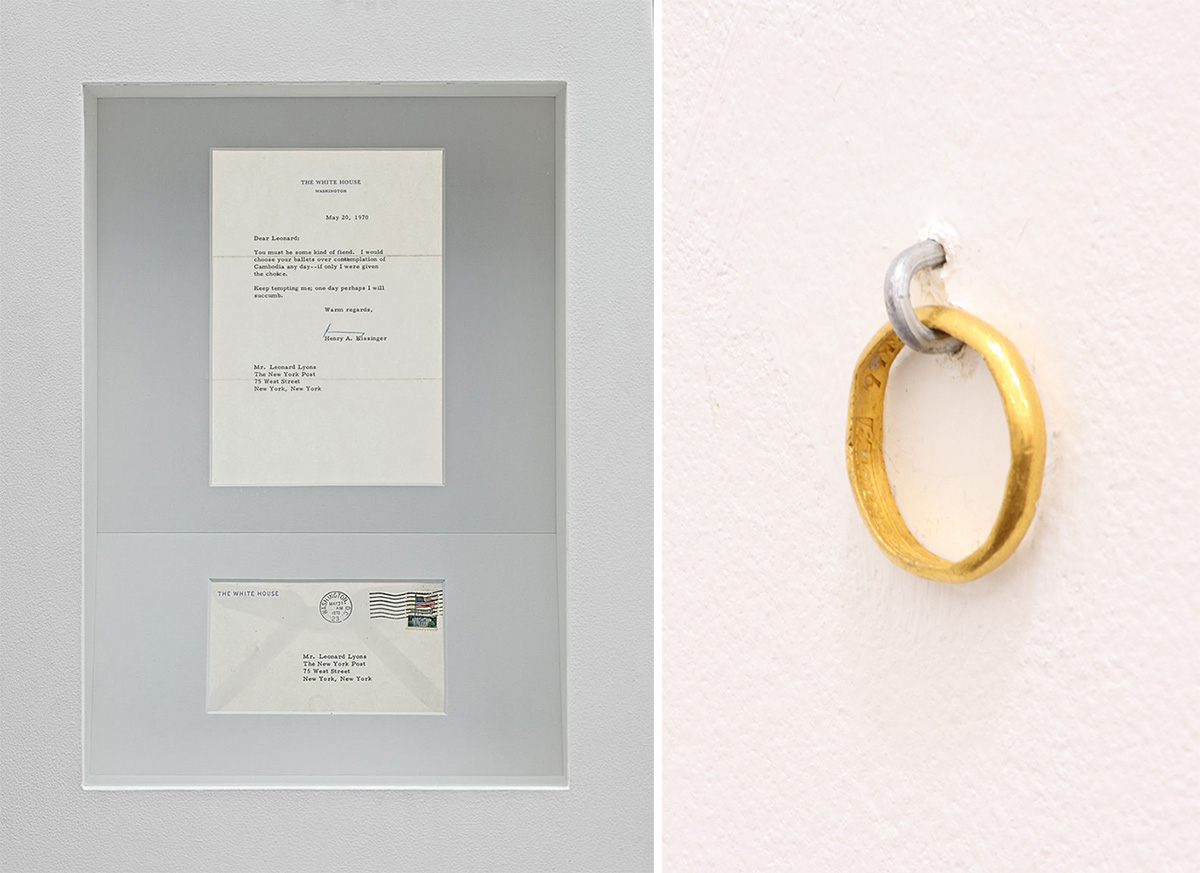

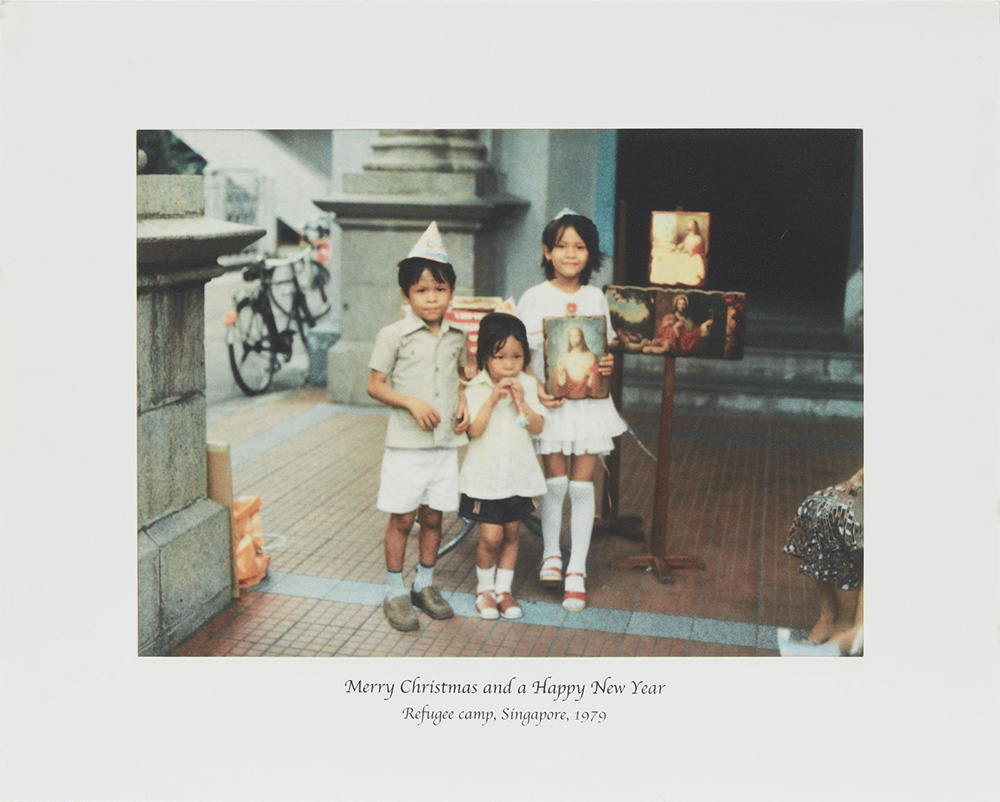

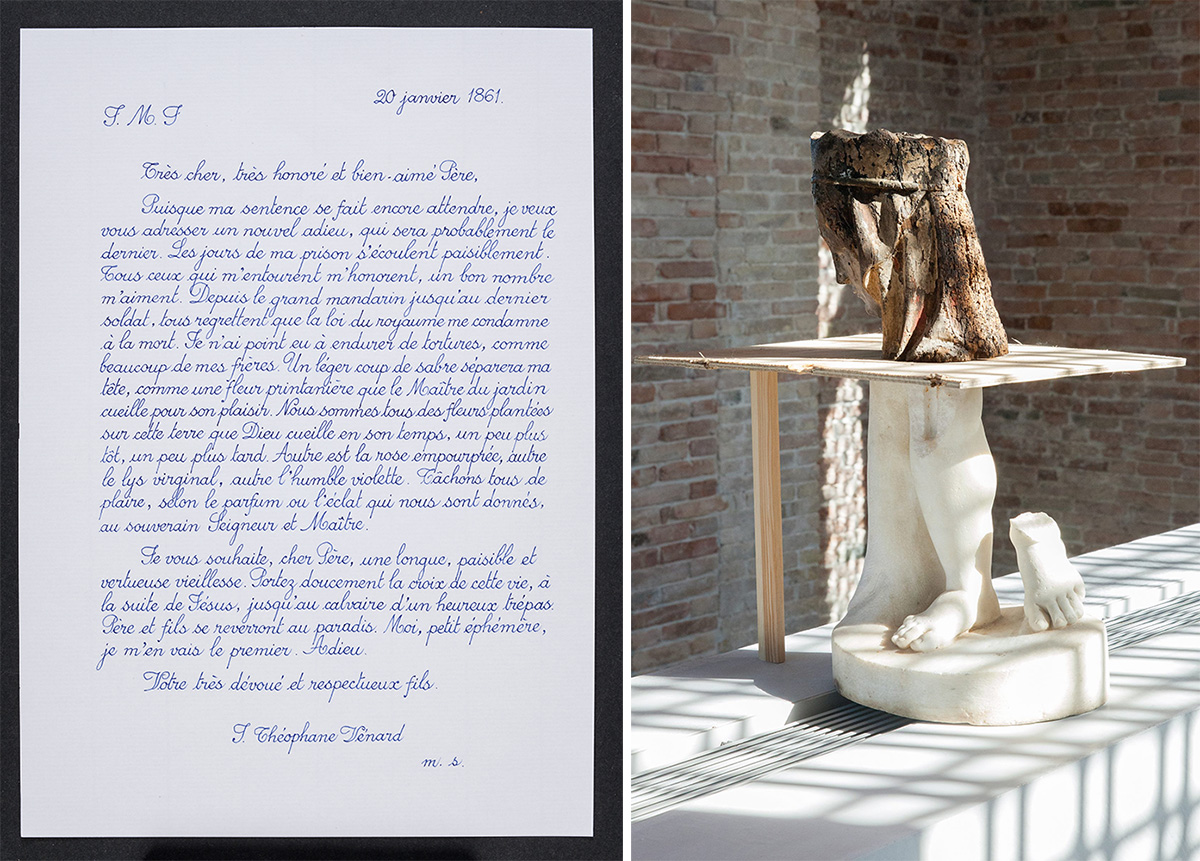

Each Danh Vo’s project grows out of a period of intense research in which historical study, fortuitous encounters, and personal relationships are woven into psychologically potent tableaux. Subjected to Vo’s vivid processes of deconstruction and recombination, found objects, documents, and images become registers of latent histories and sociopolitical fissures. In the large-scale retrospective “Danh Vo. Take My Breath Away” at the National Gallery of Denmark (SMK) are on presentation 75 artworks, including several entirely new works produced especially for SMK. At the same time Vo also takes over the museum’s Sculpture Street to present a very special project. The title of the exhibition is shared with that of the Oscar-winning song written for the action drama “Top Gun”, a film that glorifies American militarism to the extent that it prompted a significant surge in applications to U.S. forces when it was released in 1986. In his work Vo works with existing and found materials such as a classical marble sculptures, a lavish watch, a worn-out refrigerator, personal letters and historical photographs, deconstructing and combining these objects to create new works with new meaning. He often uses his personal history* as the starting point for discussing universal themes such as migration, globalisation and desire. Ranging the full spectrum of Vo’s oeuvre, from early conceptual works such as “Vo Rosasco Rasmussen” (2003), in which he married and divorced acquaintances in order to add their surnames to his own, to his recent sculptural hybrids of antique statuary, the exhibition forgo a chronological presentation, instead assembling works from the past fifteen years by their formal and thematic resonances. While the artist’s original interest in these objects stemmed from their role as witnesses to the consequences of Western intervention in the country of his birth, he was equally drawn to their dazzling decorative function. They were, he has said, “designed to make you forget, to make you leave your sorrows behind”. Significant subjects include the legacy of colonialism and the fraught status of the refugee. In particular, Vo has focused on European and U.S. influences in Southeast Asia and Latin America, examining the relationship between military interventions and more diffuse cultural incursions from forces such as evangelical Catholicism and consumer brands. Objects absorbed into the work are frequently charged by knowledge of their former ownership or their status as historical bystanders. Whether presenting the intimate possessions of his family members, a series of thank-you notes from Henry Kissinger, or the chandeliers that glittered above the signing of the 1973 Paris Peace Accords, which ended American involvement in the Vietnam War, Vo subtly excavates the internal tensions embedded in his material. “Oma Totem” (2009) stacks together a group of objects given to the artist’s maternal grandmother by an immigrant relief program upon her arrival in Germany from postwar Vietnam in 1980: a Gorenje washing machine, a Bomann mini refrigerator, and a Philips television set. This column of branded domestic commodities presents a portrait of cultural expectations for assimilation into Western culture, signaling accepted modes of lifestyle and leisure. With the addition of a large wooden crucifix that was gifted by the Catholic Church, the sculpture reduces its subject’s harrowing experience of war and exile to the set of archetypes—refugee, convert, and consumer—that were assigned to Vo’s grandmother by her new society. Several works in the exhibition feature fragments from medieval wooden sculptures of the Madonna and Child conjoined with Roman marble statuary. The profane and blasphemous phrases with which Vo has titled these sculptures, like the work “Your mother sucks cocks in Hell” (2015), share a common source as lines spoken by the demonically possessed protagonist Regan in William Friedkin’s 1973 film “The Exorcist”. The film’s interrogation of religious faith and doubt, its depiction of the dislocated body, and its themes of parental nurture and neglect all find echoes in the artist’s work. Here the Madonna’s solemnly bowed head is united with the chubby legs of an ancient marble child. The fourteen letters contained in the vitrines entitled were written by Henry Kissinger during his tenure as national security advisor and then secretary of state under Presidents Nixon and Ford. The apparently trivial notes thank Leonard Lyons, the New York Post’s theater critic, for procuring tickets to popular productions such as Hello Dolly! and Last of the Red Hot Lovers. Kissinger often declined offers that were “tempting,” “tantalizing,” or made his “mouth water” due to various conflicting official commitments. In “Untitled” (2008), one letter he rues the fact that “contemplation of Cambodia” will prevent him from attending a ballet. A reference to the covert bombing campaign waged by U.S. forces in the region, this aside juxtaposes Kissinger’s suave banter with the profound gravity of the concurrent military intervention in Southeast Asia. Three objects previously owned by the artist’s father: a Rolex watch, a Dupont lighter, and an American military class ring, have been appropriated by Vo to create “If you were to climb the Himalayas tomorrow”. Installed in a lit vitrine that conjures a luxury retail display, these items, all of which were acquired after Phung Vo’s escape from postwar Vietnam, were among his most prized personal possessions. Together they represent an aspirational portrait of masculinity and power, distilling, in the artist’s words, the associated elements of “time, fire, and war”. The work’s title is derived from an advertising slogan once used by the Rolex brand. For his display in the Sculpture Street, Vo has chosen a selection of classical sculptures from the Royal Cast Collection, combining them with circular daybeds upholstered in original fabrics by the noted textile company Kvadrat as well as with Akari paper lamps and herb beds grown in collaboration with the museum café, Kafeteria, which he took part in designing earlier this year.

*In 1979, when Danh Vo was four years old, the family fled Vietnam in a home-made boat, hoping to make a better life for themselves abroad. The intention was to reach the USA, but after a few days a Danish freighter from the shipping company Mærsk picked up the family in the Pacific Sea. Vo and his family were taken to a refugee camp in Singapore, where they waited for their application for asylum in Denmark to be processed.

Info: National Gallery of Denmark (SMK), Sølvgade 48-50, Copenhagen, Duration: 30/8-2/12/18, Days & Hours: Tue & Thu-Sun 11:00-17:00, Wed 11:00-20:00, www.smk.dk