ART-PRESENTATION: Broodthaerskabinet

The Broodthaerskabinet is a space in the S.M.A.K. for the permanent presentation of the works, editions, books and archive pieces of Marcel Broodthaers that are held in the Museum’s Collection. Broodthaers made his name as one of the most influential figures in 20tt Century art. During his lifetime, the impact of his artistic practice was not only felt in his own country. He soon made his international breakthrough with work that forms a lasting legacy.

The Broodthaerskabinet is a space in the S.M.A.K. for the permanent presentation of the works, editions, books and archive pieces of Marcel Broodthaers that are held in the Museum’s Collection. Broodthaers made his name as one of the most influential figures in 20tt Century art. During his lifetime, the impact of his artistic practice was not only felt in his own country. He soon made his international breakthrough with work that forms a lasting legacy.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: S.M.A.K. Archive

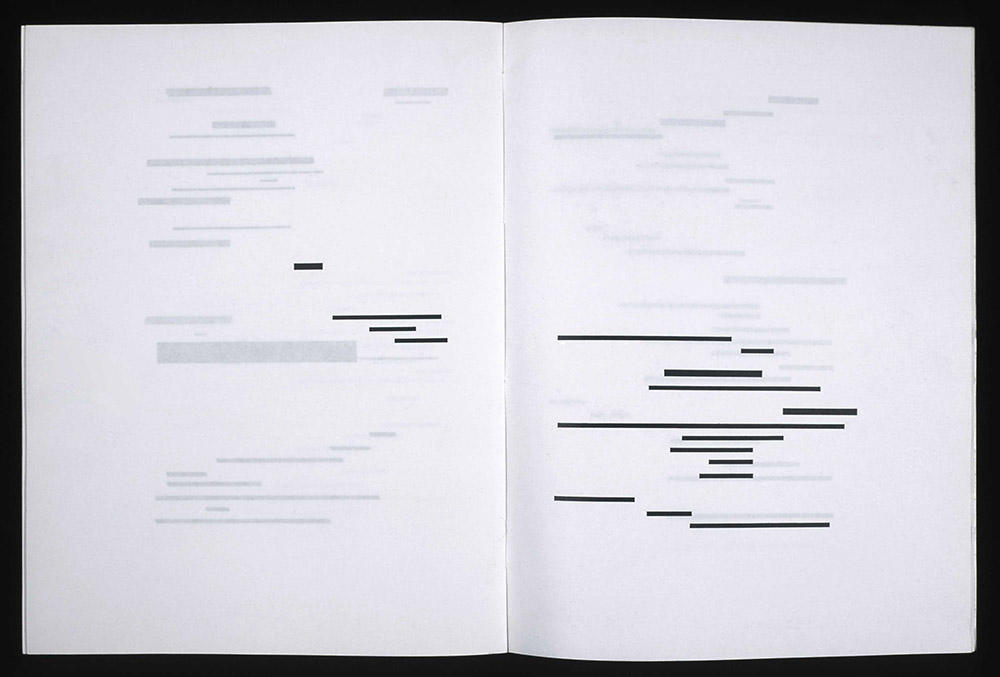

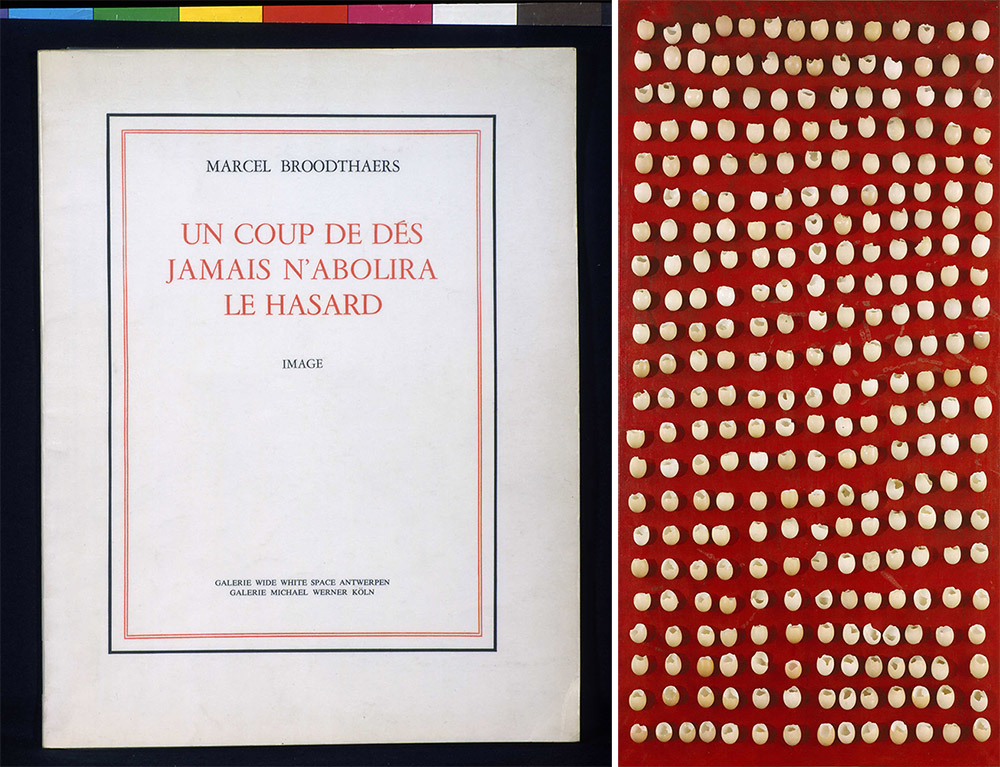

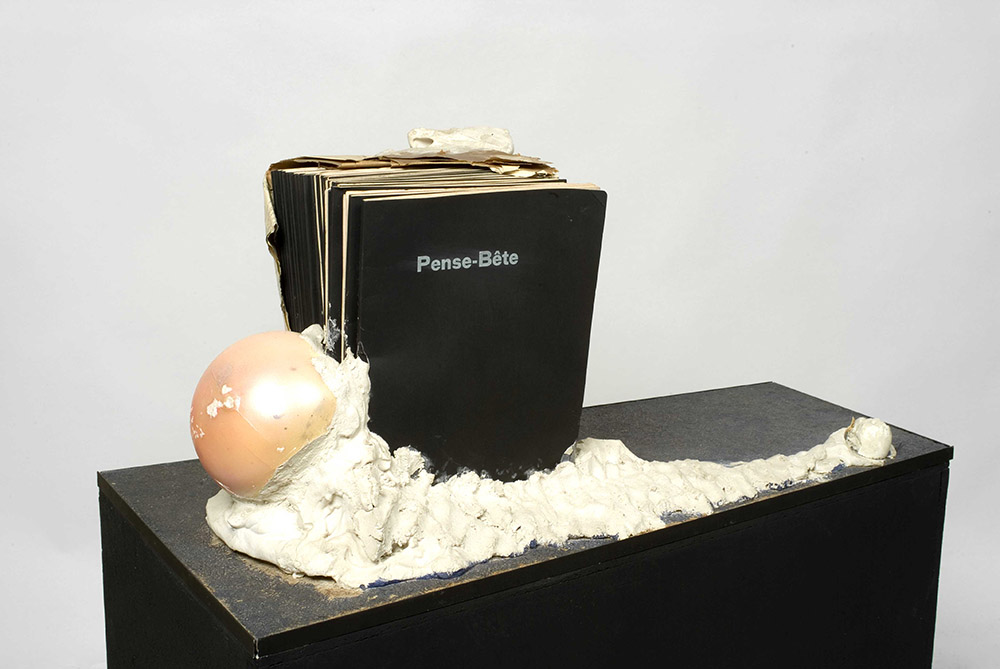

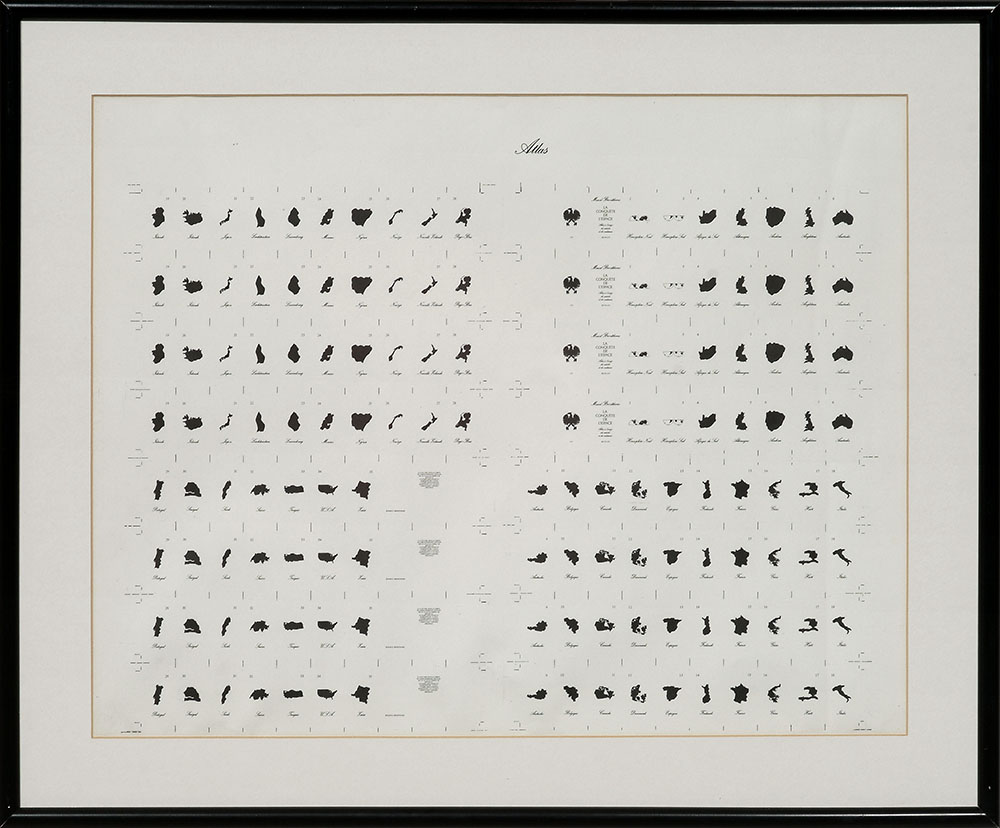

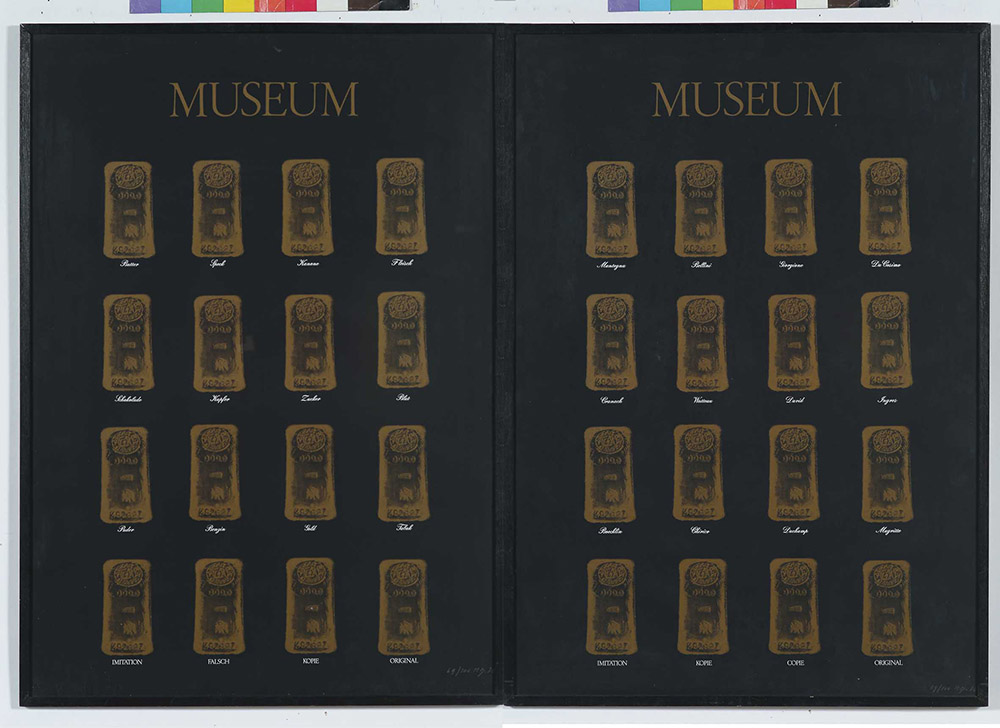

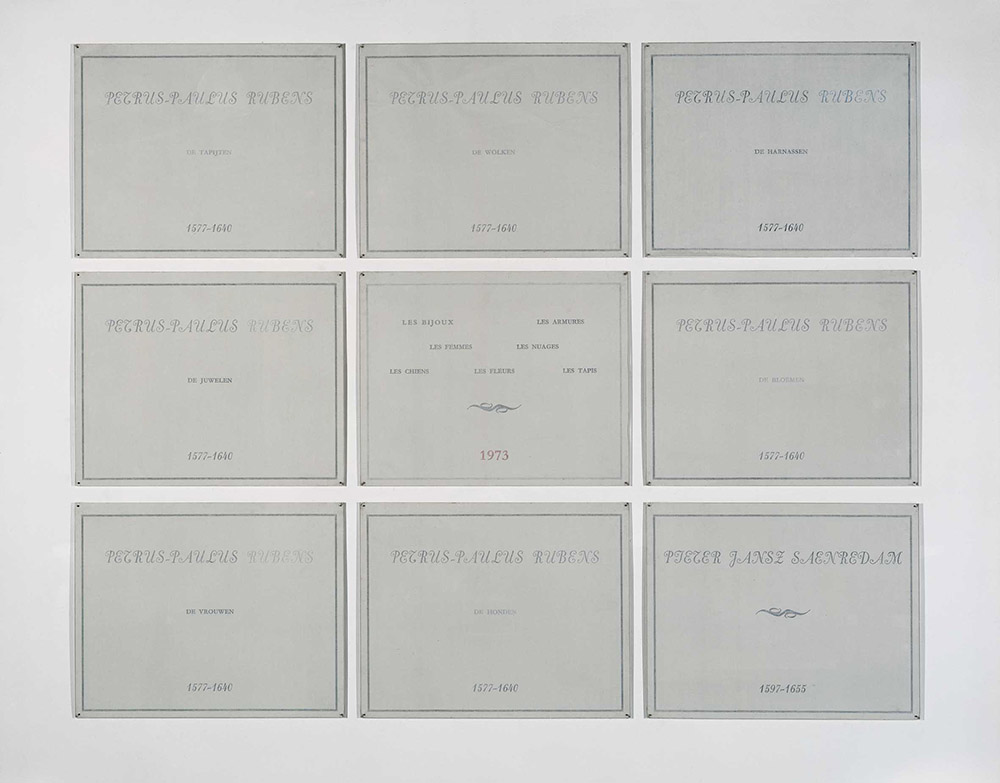

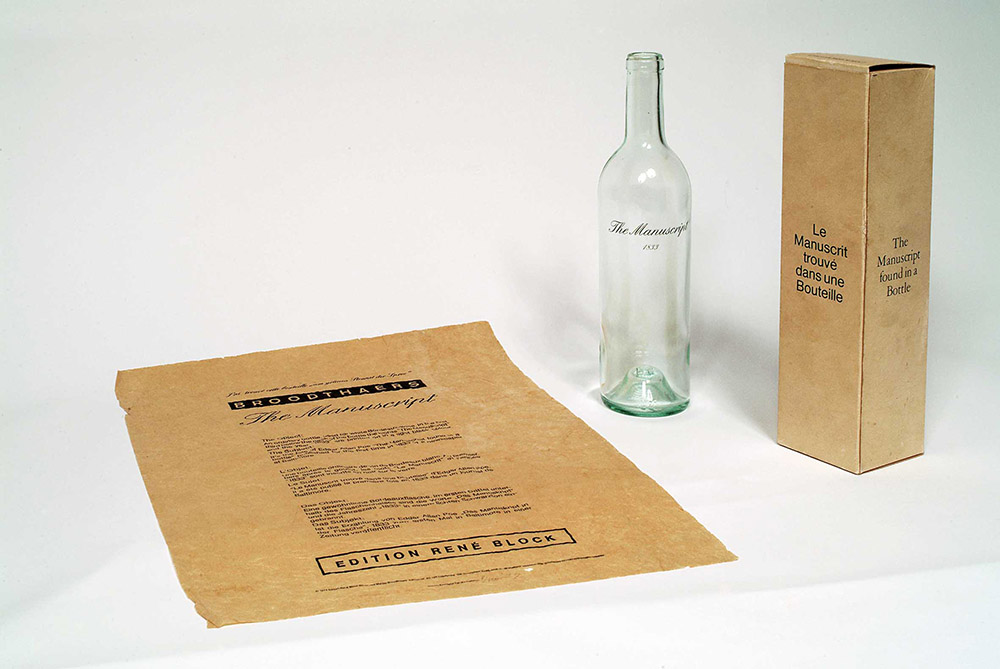

Marcel Broodthaers was born in Brussels, where he was associated with the Groupe Surréaliste-revolutionnaire from 1945 and dabbled in journalism, film, and poetry. Broodthaers’ career as an artist began with the work “Le Pense-Bête“ (1964), which is considered as the pivotal point between his life first as a poet and later as an artist. By fixing 50 of unsold copies of one of his books of poetry in a lump of plaster, he made it impossible to read them and thus made their content inaccessible. This signalled the genesis of an ‘object’, which, to his great surprise, as an art object, elicited much more interest than the poems themselves ever did. Broodthaers referred to “Le Pense-Bête” as his first “proposition artistique”, his first act as a visual artist. As a self-trained artist, Broodthaers eschewed traditional artistic skill, often making sculptures by embedding found objects in plaster. His irreverent sense of humor and love of wordplay are visible in his use of mussel shells and eggshells, which he obtained from a local restaurant and which became his signature materials. In French, the word moule means both “mussel” and “mold”; in Broodthaers’s hands, the discarded shells gave form to artworks with multitudes of poetic meanings. Ever skeptical of authority, Broodthaers made work that reflected his political concerns, and he harnessed Belgian associations with mussel shells, coal, and frites (fries) in order to confront his national identity. For the remainder of his life, he frequently returned to these objects, altering their presentations, creating photographic reproductions, and exhibiting them in new contexts. In 1968, Broodthaers announced that he was no longer an artist and appointed himself director of his own museum, which he called the Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles . Instead of being dedicated to the display of artworks, it often focused on a museum’s supporting activities, such as documentation, publicity, and finance, which Broodthaers represented through announcements, publications, films, slide projections, and objects. Conceived in the aftermath of the 1968 student protests against the war in Vietnam and inequality worldwide, Broodthaers’s project provided a richly layered commentary on the role of art and the function of the Museum in society. Assuming the role of an authority figure, he critiqued the museum from within. Over the course of four years Broodthaers rolled out 12 temporary presentations of the Musée d’Art Moderne, which he called “sections”, in seven European cities. Dispersed geographically and largely ephemeral, the project was never intended to be viewed as a whole. In 1972, Broodthaers concluded his tenure as the self-appointed director of the Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles and declared that he was becoming an artist again. He signaled his return to art making by developing a new form of painting, one that never required him to pick up a paintbrush. To create his “Peintures littéraires” Broodthaers printed words onto canvas, and he hired a sign painter to inscribe a number of words, including toile (canvas) and huile (oil), on the walls and ceiling. From 1974 until his death in 1976, Broodthaers organized immersive large-scale displays in which examples of his past work were shown with new works and borrowed objects. He called these exhibitions Décors. By doing so, and by employing outdated installation tropes like palm trees, carpets, 19th-century display cases, Broodthaers evoked ideas of decoration, ornamentation, and theater that starkly contrasted with the modernist slogan “art for art’s sake.” In French, the word décor also suggests a film set, and, fittingly, Broodthaers shot a number of films in his retrospectives, harking back to his first film, “La Clef de l’horloge, Poème cinématographique en l’honneur de Kurt Schwitters” (1956), shot for an exhibition of work by Kurt Schwitters at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels. Besides an exhibition room, the Broodthaerskabinet will also be a forum for exhibitions, (archival) presentations, talks, colloquia and similar events, compiled and organised by artists, friends, curators, experts and others who wish to gain more in-depth insights into Marcel Broodthaers’ oeuvre.

Info: S.M.A.K., Jan Hoetplein 1, Gent, Duration: 2/6-2/9/18 Days & Hours: Tue-Fri 9:30-17:30, Sat-Sun 10:00-18:00, http://smak.be