ART-PRESENTATION:An Incomplete History Of Protest, Part I

The exhibition “An Incomplete History of Protest: Selections from the Whitney’s Collection, 1940–2017” exhamine how artists from the 1940s to the present have confronted the political and social issues of their day. Whether making art as a form of activism, criticism, instruction, or inspiration, the featured artists see their work as essential to challenging established thought and creating a more equitable culture (Part II).

The exhibition “An Incomplete History of Protest: Selections from the Whitney’s Collection, 1940–2017” exhamine how artists from the 1940s to the present have confronted the political and social issues of their day. Whether making art as a form of activism, criticism, instruction, or inspiration, the featured artists see their work as essential to challenging established thought and creating a more equitable culture (Part II).

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Whitney Museum Archive

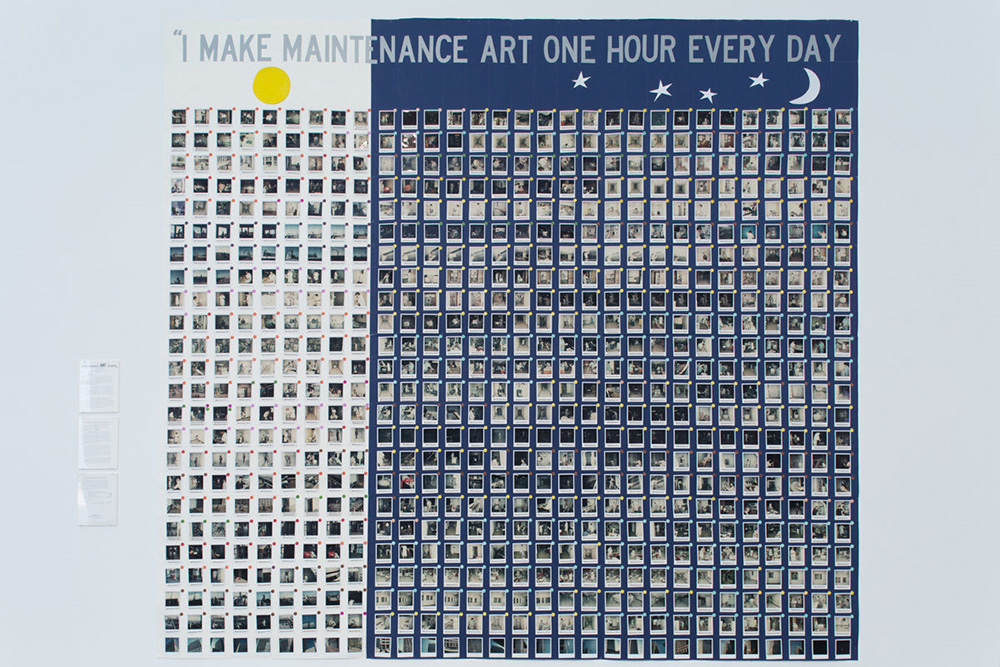

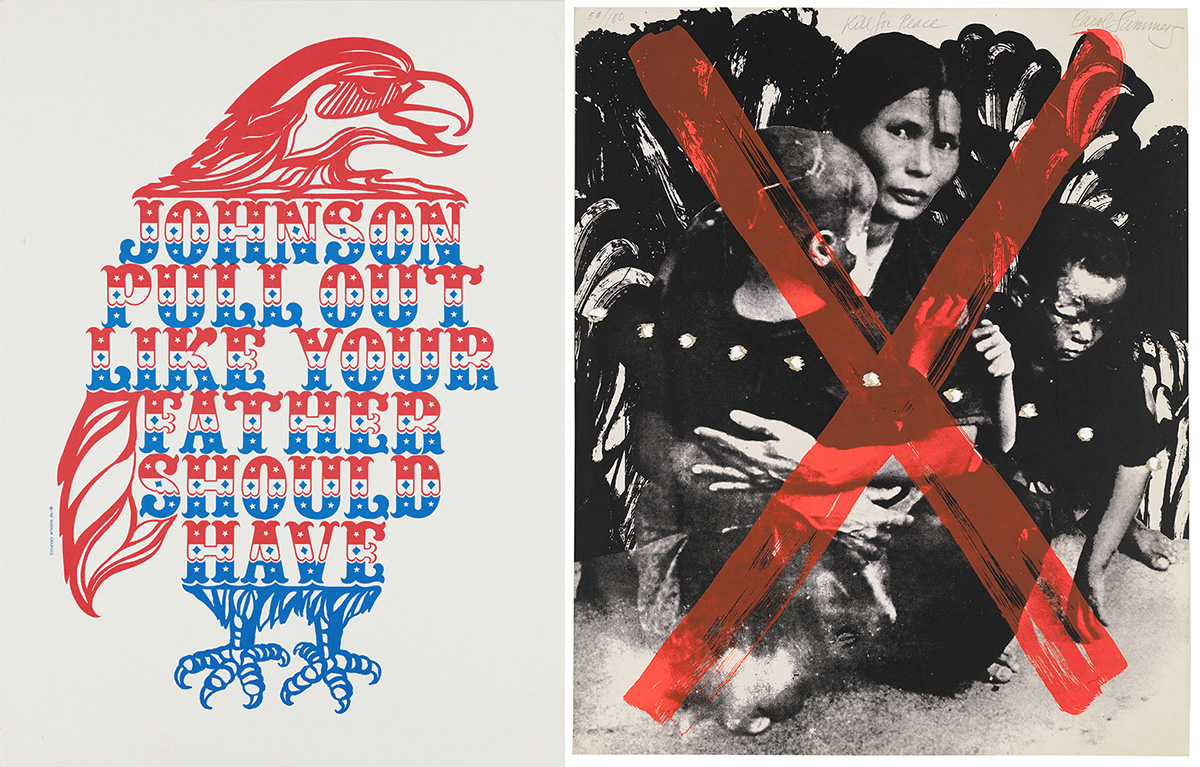

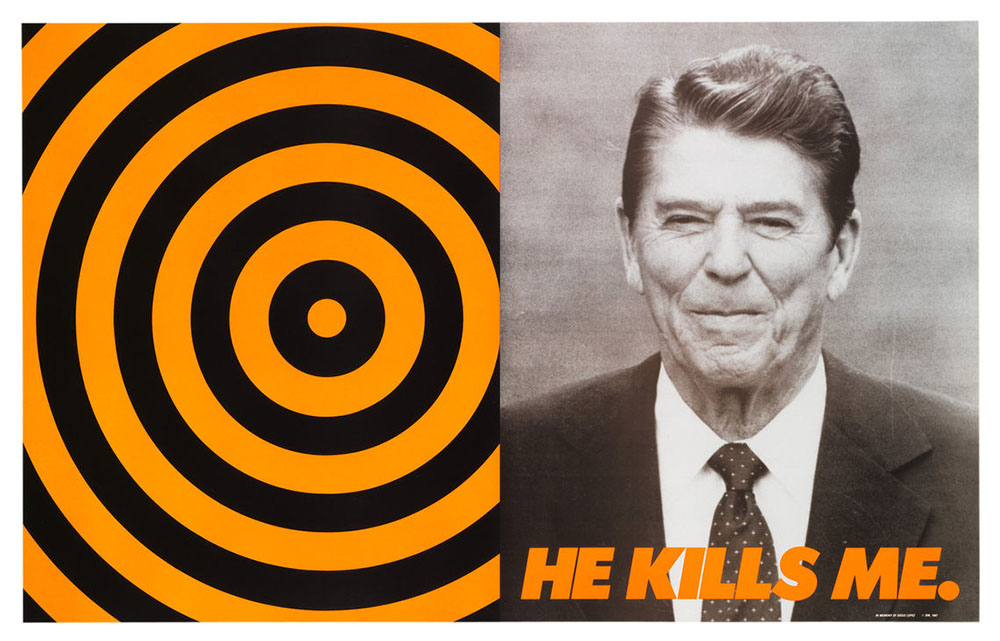

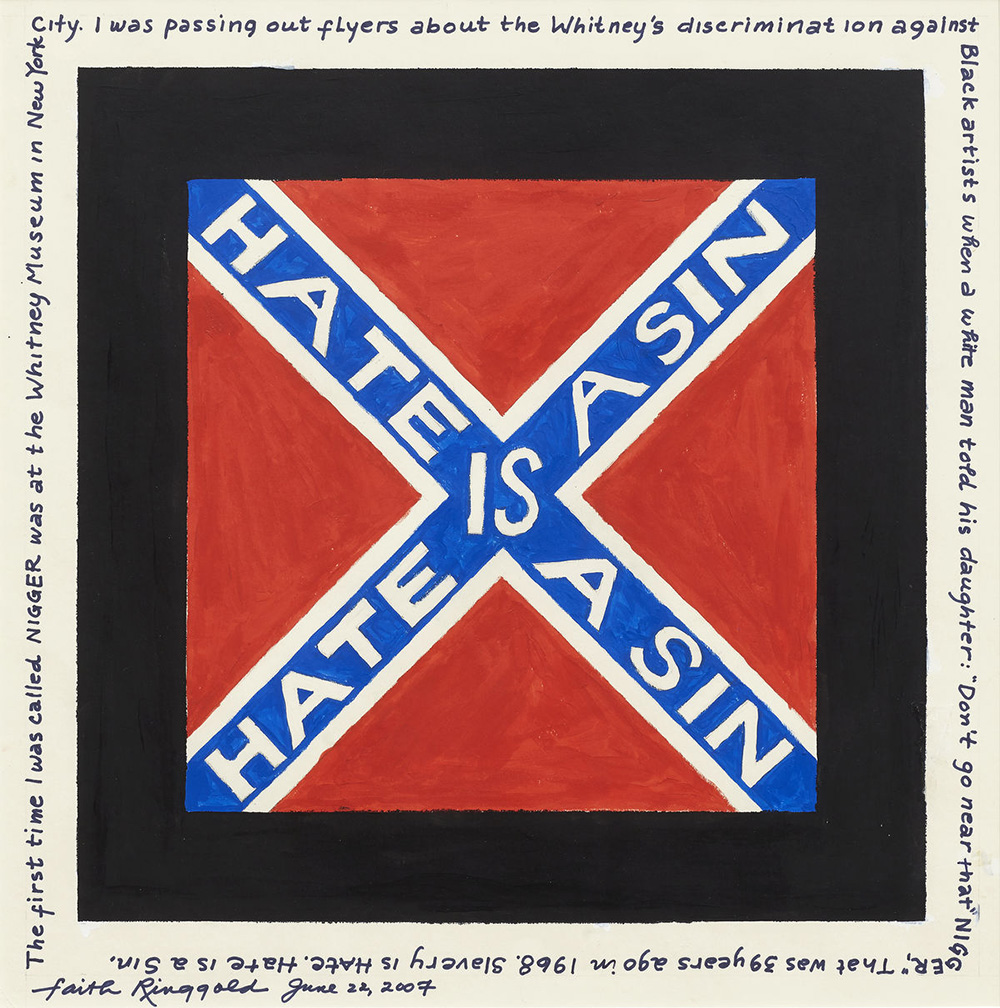

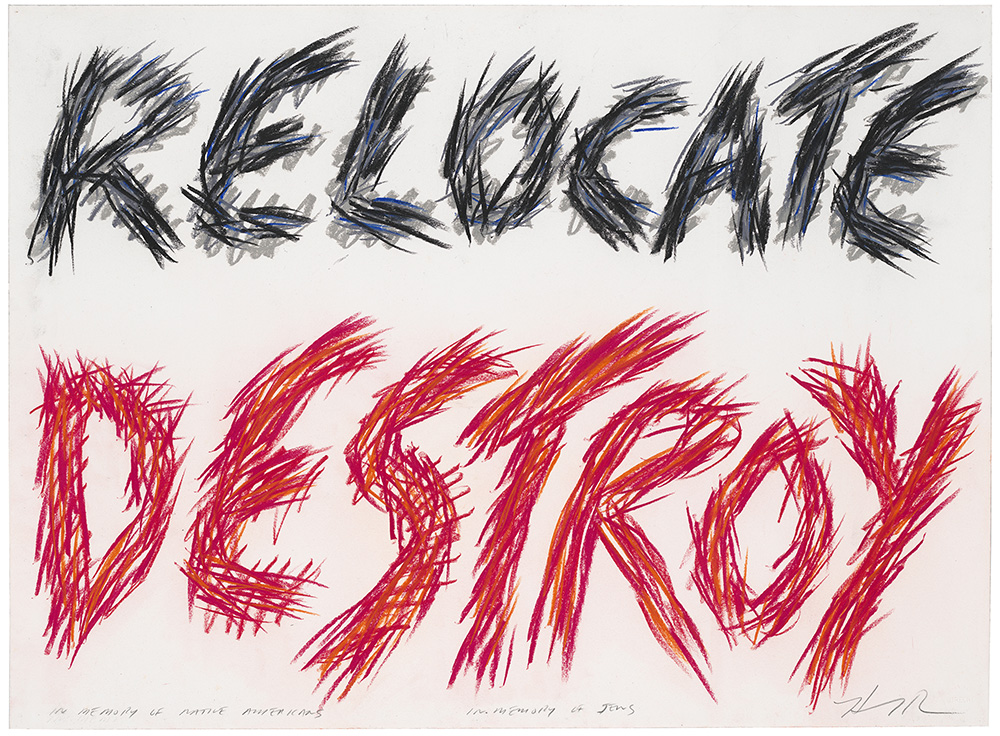

American artists in the mid-20th Century used ideas of resistance and refusal to reject inherited policies, politics, and social norms. For some, like Toyo Miyatake, the very act of making art was a form of disobedience. He documented his internment after smuggling camera parts into the camp in Manzanar, California, where he and other Japanese Americans were held during World War II. For Larry Fink, photographing the beatniks during the 1950s gave visibility to a population that formed its identity in opposition to a conformist cultural mainstream. Other projects, like those by Louis H. Draper and Gordon Parks, recorded the efforts of those fighting against racist politics and policies for the fundamental right to be part of society. Ad Reinhardt, working in the aftermath of World War II, defined his art mainly by what it was not. His black paintings were “non-objective, timeless, spaceless, changeless, relationless, disinterested”. Although described in aesthetic terms, Reinhardt’s disavowal can also be seen as a stand against the heroic cultural ideology that led to repression and war. Material gathered from the Whitney Archives from 1960 to 1971 examines moments of collective, artist-led engagement with the Museum, as well as frequent opposition to it. During the war in Vietnam and the fight for civil and women’s rights, museums increasingly became sites of political action and protest. No longer seen as immune to the social struggles of the day, they were viewed by artists as symptoms of the larger culture’s ills or, at the very least, mirrors of its values. From disputes over the curatorial direction of the Museum to demands that it be more inclusive and accessible, artists have shaped the course of the Whitney and continue to do so today. Included in the exhibition are two artists who chose personal, oblique, and allusive means to question how social spaces are made, engaged, and controlled. Although working abstractly, Senga Nengudi and Melvin Edwards explore how space can be considered in relation to gender and race. Made from nylon hosiery, a material that strongly suggests skin, Senga Nengudi’s “Internal I” (1977) evokes the resilience and fragility of the female body upon entering and being defined by society. Its bilaterally symmetrical form calls to mind a human figure that has been brutally stretched and flayed. Constructed from barbed wire, Melvin Edwards’s “Pyramid Up and Down Pyramid” (1969) was included in solo exhibition at the Whitney in 1970. The work’s material connotes prisons, animal pens, and physical pain within the vocabulary of minimal sculpture. According to the U.S. National Archives, there were 58,220 American military casualties during the war in Vietnam. The number of Vietnamese military and civilian deaths has been estimated at one to three million. Opposition to the war, which had started on college campuses in the early 1960s, was catalyzed largely by protests. Posters were essential tools of education and persuasion in the antiwar movement. Produced rapidly and often distributed at no charge, they appeared on placards, in public spaces, and on the walls of college dorm rooms. Like Internet memes today, they combined image and text in compelling, graphically innovative ways; they were lacerating in their critique and often brimmed with satire and gallows humor. In addition to calling for direct political action, artists made singular works that addressed the war in Vietnam. Edward Kienholz’s “The Non War Memorial” (1970) simulates the carnage with sand-stuffed military uniforms scattered on the floor as if they are corpses. Nancy Spero brings the conflict home through her powerful and elegiac work “Hours of the Night” (1974), the title of which is borrowed from the Egyptian Book of the Dead. Allusive and poetic, with texts referencing a fire in her apartment alongside torture in Vietnam, the work suggests how the war crept into every corner of American life. In the 1960s, the feminist movement grew increasingly vocal and influential. Advocating for the legal and social rights of women, it addressed reproductive freedom, domestic and sexual violence, and the family, among other pressing concerns. These works focus on feminist explorations of labor, whether in the home or workplace. The slogan “the personal is political” became both rallying cry and directive in this period for many artists, both male and female, who often used video and photography to give visibility to their lived experiences. Suzanne Lacy and Martha Rosler employ absurdity and humor to suggest that meaning and gendered roles are socially constructed. In her “Free, White and 21” (1980), Howardena Pindell details her experiences with racism and sexism in both the feminist movement and in jobs, calling attention to the specific mental and emotional labor required of people of color in white-dominated spaces. Since the 1980s, the Guerrilla Girls have unmasked the unequal status of women as art workers and fought for the inclusion of women and people of color in major art institutions. During the 1980s and 1990s, AIDS and complications from it killed nearly half a million people in the United States, a disproportionate number of them gay men and people of color. AIDS became one of the most searing issues in American life and politics. The artistic community lost thousands; still more friends, lovers, and family members faced lives transformed by grief, fear, indignation, and illness. The activist and critic Douglas Crimp argued that both “mourning and militancy” were required to address the AIDS crisis. Many artists made activist work that criticized government inaction, promoted awareness and treatment, and expressed support for people fighting and living with the virus. Frequently adopting the visual strategies of previous protest movements, artists mobilized against AIDS by deploying a sophisticated understanding of media culture, advertising, and product branding. Their widely distributed posters, artworks, and graphics were often used at marches and rallies or were posted on the street. In a different mode, AA Bronson’s billboard-size portrait of his friend and collaborator Felix Partz transforms a private image into a public statement. Partz is pictured just a few hours after his death from AIDS-related complications. By making viewers confront the image of someone who lived with AIDS and the rawness of his death, Bronson uses the memorial form to protest the magnitude of the crisis. In the 1990s, artists witnessed the persistence of racialized violence in American society and responded with newfound urgency. Two groundbreaking and controversial exhibitions at the Whitney, the 1993 Biennial and “Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary American Art” (1994), tackled this issue directly. The Museum acquired works by Mel Chin and Carl Pope after they were shown in “Black Male”. Purposefully confrontational, the artists and their artworks speak unapologetically about painful aspects of American history and question state-sanctioned systems of authority. These works are exhibited with the understanding that this history of systemic violence is not past. Rather than relying on a single social issue as its organizing principle, the exhibition gathers artworks largely made after 2000 that evoke the concept that a self-conscious examination of historical figures, moments, and symbols can shape current and future political formation. Many artists today are looking to the past to understand their present as well as to explore the possibilities, and the possible failure, of collective action. While some of the artworks demonstrate how memory can inform models of protest and activism now, others reveal how nostalgia can make it difficult to move forward. A 2005 film by Josephine Meckseper documents protests against the war in Iraq. By using Super 8 film, a format released in 1965, the imbues a contemporary action with a 1960s aesthetic. The film suggests both that yesterday’s counterculture can become today’s style and that we can learn from the past to address the needs of the present.

Info: Curator: David Breslin, Assistant Curator: Jennie Goldstein, David Kiehl and Margaret kross, Whitney Museum of American Art, 99 Gansevoort Street, New York, Duration: 18/8/17-27/8/18, Days & Hours: Mon-Thu & Sun 10:300-18:00, Fri-Sat 10:30-22:00, www.whitney.org