ART-PRESENTATION: The Reconfigured Landscape,Part II

The exhibition “The Reconfigured Landscape” features a selection of works from the Fundación Botín Collection. It surveys different ways of representing our surrounding world, while also offering a historical overview of Fundación Botín’s ongoing engagement with the visual arts over the last ten years. Many of the works on view are exhibited here for the first time (Part I).

The exhibition “The Reconfigured Landscape” features a selection of works from the Fundación Botín Collection. It surveys different ways of representing our surrounding world, while also offering a historical overview of Fundación Botín’s ongoing engagement with the visual arts over the last ten years. Many of the works on view are exhibited here for the first time (Part I).

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Fundación Botín Archive

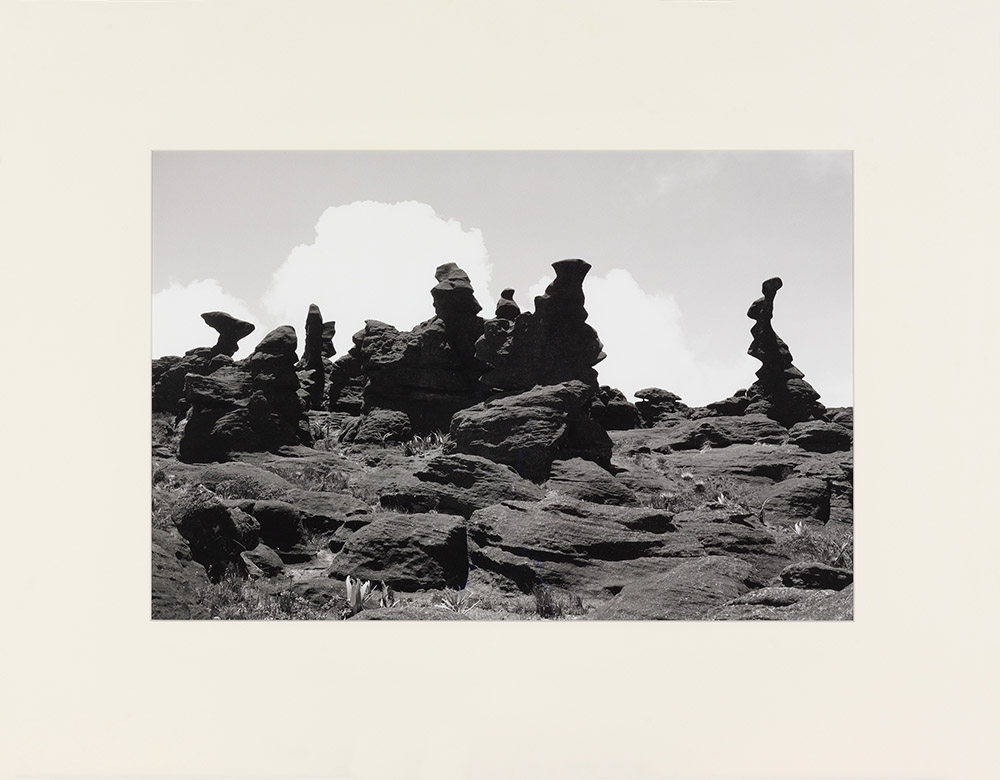

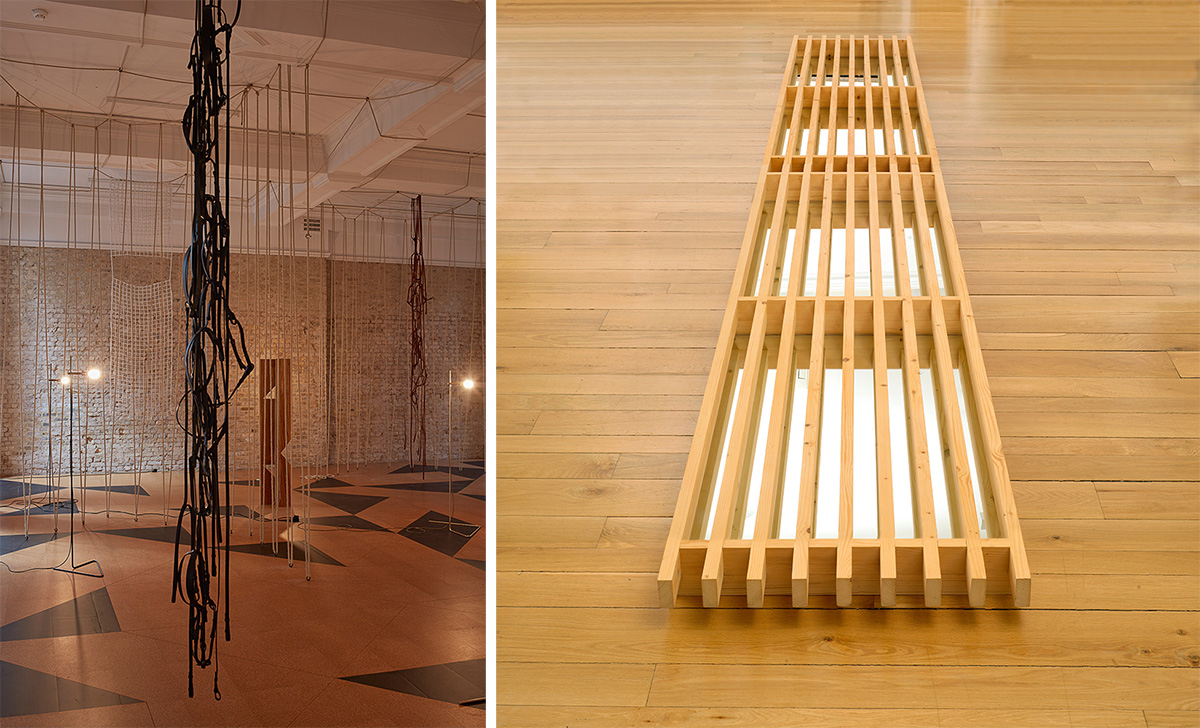

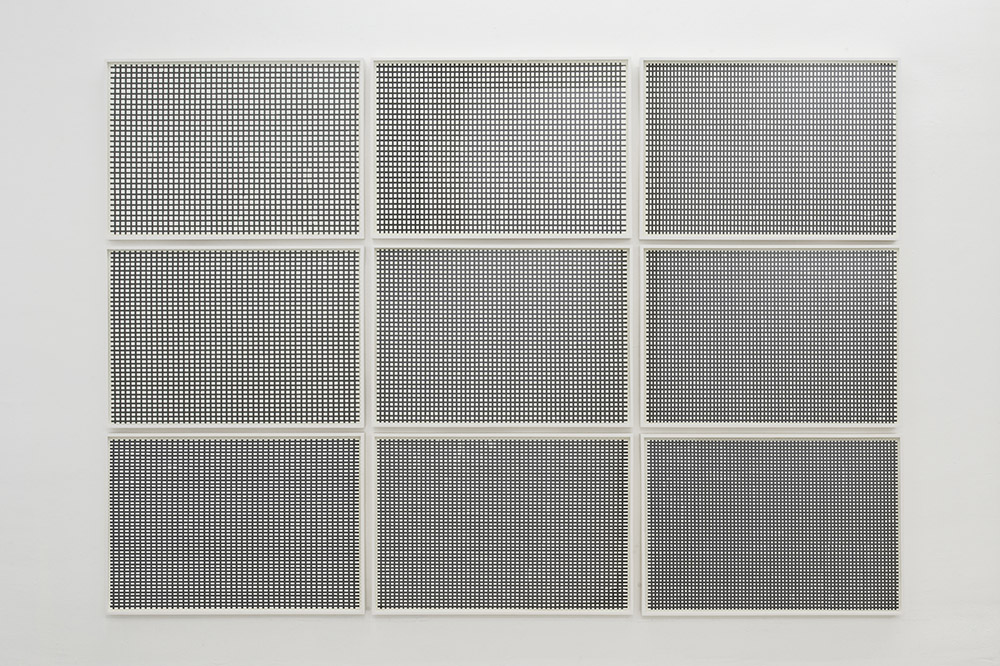

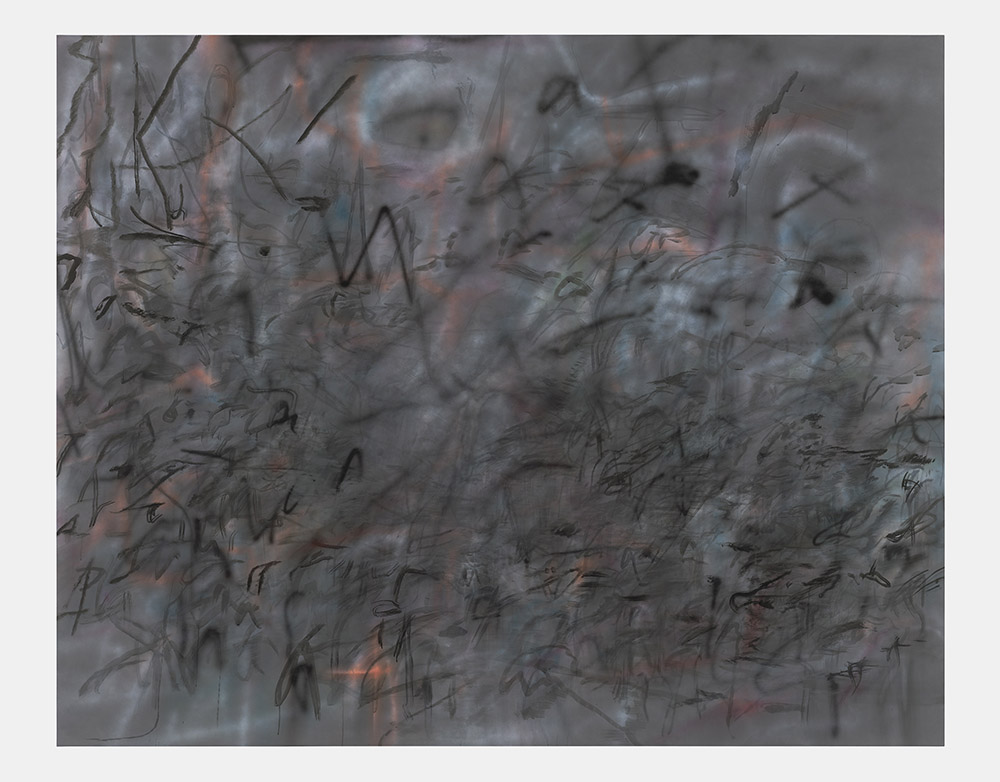

All the artists in the Collection either directed a Fundación Botín’s Visual Arts workshops or once was a recipient of a Fundación Botín Visual Arts Grant. The mix of generations is an important dynamic of the Fundación Botín Collection. It provides an interesting perspective on artistic practice in the 21st Century, and mirrors the formal freedom artists have consolidated over the past fifty years. In addition to painting, drawing and sculpture, the exhibition includes videos and multimedia installations, a form that perhaps epitomizes the forefront of artistic research in the past few decades. On this journey through the visual arts of the last decade, Leonor Antunes envisions sculpture in relation to the space it is presented in. “Random intersection #14” is part of a series started in 2007, whose design refers directly to horse bridles, and is inspired by collages made by the Italian architect Carlo Molino as preparatory work for his plans for the Società Ippica Torinese (These harness-like structures are connected to the space with an intricate network of hemp rope, creating a kind of ghostly presence in the space, in contrast with the density of the surrounding architecture. The work of Lothar Baumgarten questions Western systems of thought and representation, as well as the ways its perception of and relation to other cultures are constructed. From 1977 to 1986, he travelled to primal forests in Central America, and lived with autochthonous tribes who had had little contact with the outside world. His photographs reflect upon how Western fantasies of paradise and indigenous people’s lives contrast heavily with living conditions systematically degraded by international conglomerates. The wall painting lists the names of indigenous tribes, and the territories they still occupy. Collecting objects and architectural fragments is core to the work of Jacobo Castellano. He accumulates them until they find their way into his elaborate sculptural compositions. As a result, the sculptures, made of fragments of wood furniture or architectural elements, and completed with objects and artefacts, become like snapshots of mingled past histories. Tacita Dean makes films using celluloid, whose physical handling relates to drawing and sculpture, other mediums she uses in her work. Her 35mm film is titled after the initials of British author J.G. Ballard (1930-2009), with whom Dean enjoyed a long-running correspondence based on their mutual interest in Robert Smithson’s iconic earthwork and related film, “Spiral Jetty” (both works, 1970). The connections between Ballard’s fiction and Smithson’s earthwork are unequivocal. “JG” is a meditation on time—human, prehistoric and cosmic—that also ponders the notion of landscape, and more specifically the loss of scale and a certain sense of timelessness one can experience in a desert. Fernanda Fragateiro has unfolded a body of work that reflects upon the impact of architecture on human interaction, but also its sculptural quality. Most of her works take their formal cue from architectural details or fragments, while she often uses found construction material she gathers while roaming around the city. “Um caminho que não é um camino” is a replica of a duckboard pathway she encountered while scouting the grounds of Ciudad Abierta (Open City). In her work, Irene Kolpelman documents her keen observation of the environment with large series of drawings, in an attempt to decipher the way knowledge is produced and shared. In doing so, she also reflects upon the way scientists and naturalists have eschewed the empirical for a more rational and structured manner of understanding nature, and elaborated all kinds of systems of classification, something that may explain how art and science have parted ways when they once seemed to be much closer. “Indexing Water” was produced in collaboration with with Marcel Wernand, a doctor in Physical Oceanography at NIOZ (Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research). Sol Lewitt was a key proponent of a new way of envisaging the work of art. Dissociating the idea from the process of production, he conceived his Wall Drawings as a set of instructions anyone could execute. Those works therefore exist in a dematerialized form until someone produces them directly on the wall of the exhibition space, scaling them according to the dimensions of each venue. Wall Drawings are erased so they can be executed again on a new wall: they are always subject to new interpretations, not unlike musical scores. The colour scheme is based on four colours: yellow, red, blue and black; while all the geometric forms are derived from a single line inclined in a different direction – vertical, horizontal, or oblique. LeWitt started producing Wall Drawings in 1968 and continued producing new ones until his death. “Wall Drawing #499, Flat-topped pyramid with color ink washes superimposed” was first produced in 1986 in New York. Julie Mehretu is represented in the collection with “Epigraph, Damascus” (2016) – a six-panels large-scale print and “Conjured Parts (Sekhmet)” a 2016 painting. Her multi-layered compositions express the complexity of a globalized realm in which the advent of high-speed networked communication has profoundly transformed our perception of space and time. They depict a world in a state of chaos, and denote the artist’s persistent engagement with social and political urgencies. Both the painting and prints are part of a recent body of work, which relates to the civil war in Syria. Core to Sara Ramo’s artistic research, is her interest in how conventions and rituals vary from one culture to another and how this affects perception and understanding. Having split her life between Spain and Brazil, from very early on, Ramo experienced these differences personally. Brazil also happens to be a place where many different cultural influences have blended into each other. “Os Adjudantes” is the second in a trilogy of short films that focuses on music performances. Indeed, rituals for experiencing music vary drastically from a concert hall to a ritual dance or other spiritual undertakings in primal cultures. Blending various cultural references, Ramo stages rituals of her own invention. She confronts the viewer with the way s/he creates meaning, consciously or not. Finally, the exhibition also includes the work of Oriol Vilanova which is rooted in collecting and classifying artefacts. His specific interest lies in postcards, which exacerbate the clichéd vision one may have of a place; in that sense, they are a testimony to how tourism tends to oversimplify the world to make it more decipherable, more consumable. What may appear neutral is in fact telling of how a culture chooses to represent itself. Exhibited as a whole, these collections become meta-images, with each unit acting as a kind of pixel or building block. “Si la noche fuese un color” is made up of 700 postcards of night-time landscapes.

Info: Fundación Botín, Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola 3, Santander, Spain, Duration: 23/6/18-13/1/19, Days & Hours: Summer (June-September [Closed on Mon 16/7-27/8]) 10:00-1:00, Winter (October-May) 10:00-20:00, www.centrobotin.org