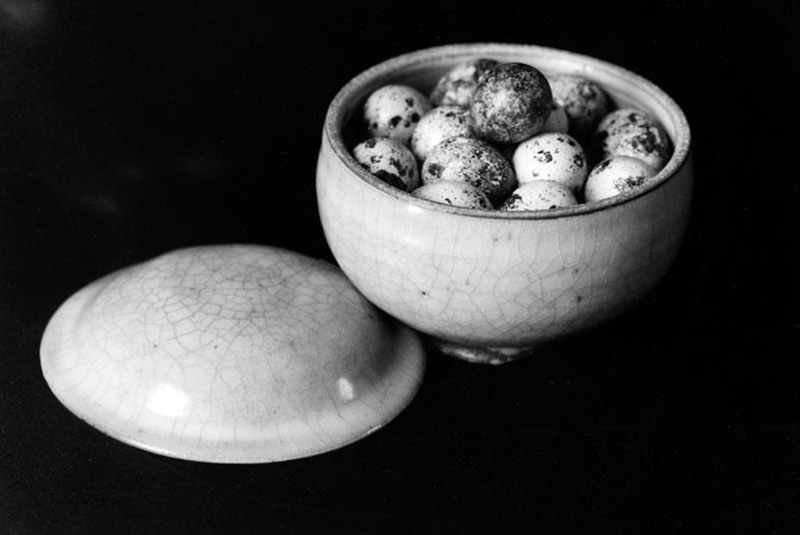

PHOTO:Imogen Cunningham-Seen & Unseen

Imogen Cunningham was an American photographer whose intimate portraits and floral still lifes are characterized by their evocative light and attention to detail. Her photographs reflect vital developments in 20th Century art and photography. She is recognized for helping to establish photography as an art form. Never tied to one style of photography or subject, Cunningham had a signature view in what she created. Working for over seventy years, her photographs are seductive and dynamic and inspired by a multitude of sources. Cunningham was one of the most experimental photographers in her lifetime.

Imogen Cunningham was an American photographer whose intimate portraits and floral still lifes are characterized by their evocative light and attention to detail. Her photographs reflect vital developments in 20th Century art and photography. She is recognized for helping to establish photography as an art form. Never tied to one style of photography or subject, Cunningham had a signature view in what she created. Working for over seventy years, her photographs are seductive and dynamic and inspired by a multitude of sources. Cunningham was one of the most experimental photographers in her lifetime.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Fenimore Art Museum Archive

The retrospective “Seen & Unseen: Photographs by Imogen Cunningham” at , Fenimore Art Museum showcases one of the most influential and innovative photographers in the history of the medium. The exhibition features 60 of Cunningham’s best works of art as well as camera equipment and archival materials. Imogen Cunningham was born in Oregon on 12/4/1883 and grew up in Washington. After some study of drawing and painting as a child, Imogen became fascinated with photography. In 1901, at age 18, she purchased a 4 x 5” view camera by mail order and taught herself. Soon she decided to study photography seriously. The nearest college, The University of Washington, offered no art classes, but a degree in chemistry was a practical solution for a young photographer. Imogen enrolled in 1903 and earned her tuition by making lantern slides for the botany department, and later she worked for Edward Curtis in his Seattle studio, printing his images of the North American Indians. In 1906, among her first art photographs of still lifes and portraits of friends and family members, Imogen posed herself nude in the grass, in a secluded part of the university campus. Shortly after graduation, in 1909, Imogen received a $500 grant from her sorority that enabled her to study photographic chemistry in Dresden. Her thesis, which she wrote in German, advocated the versatility of using of hand-coated printing papers. She described a new method of making platinum photographs, using lead chemistry and brown-toning them. Her formulas are still useful today. After a year in Dresden Imogen returned, by way of Paris, London, Philadelphia, and Washington D.C. She postponed her long train ride home to stay in New York a few extra days, in order to meet Alfred Stieglitz. Stieglitz was impressed by the young photographer and introduced her to Gertrude Käsebier, a co-founder of his Photo-Secession group and the first woman to establish a commercial photography studio. Fortified by their praise, Imogen immediately started her own portrait studio in Seattle. Its success gave her great prominence among the other artists of the region. Imogen began to create art photographs as well, usually allegorical tableaux with friends posing as subjects, in the painterly, romantic “pictorial” style dominant at that time. In 1914 she had her first solo exhibition, at the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, New York. In 1915, Imogen married Roi Partridge, an accomplished etcher. In 1918 Imogen decided to relocate the family to California, and Roi accepted an offer to teach in San Francisco. When they moved, Imogen had to destroy most of her glass plate negatives and she carried only a small collection of her early prints with her. During the 1920s, developments for Imogen herself were remarkable — and the future of photography was changed. In 1921 her visualization suddenly refined her work, changing her camera focus from long to near, seeking out details and patterns and forms. In portraits, her previous pictorialist style was replaced by an emphasis upon clarity, precision, and persona. In the 1920s Imogen’s circle of protégés expanded, to include friendships with Maynard Dixon and Dorothea Lange, Edward Weston and his associates Johan Hagemeyer and Margrethe Mather. She discovered that the distillation of plant forms was also finding expression in the botanical photographs of Albert Renger-Patzsch, Ernst Fuhrmann and Karl Blossfeldt. Imogen’s collaboration with Edward Weston led to their forming the purist movement Group f/64, which insisted on sharply-defined images and tonal gradation. In 1932 they exhibited their new works, with Consuelo Kanaga and Sonya Noskowiak, as “Group f/64,” at the de Young Museum in San Francisco. During the 1930s, Imogen’s art photographs were well and widely exhibited, including solo shows at the Dallas Art Museum, the Crocker Gallery in Sacramento, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. In the early 1940s, she sold her house in Oakland and shared a studio and darkroom, until she settled into what would be her final address, 1331 Green Street, San Francisco. Imogen produced some of her finest portraits in the 1950s, a diverse array of street photography, and images of artists and writers, penetrating studies that disclose the physical and emotional dimensions of her subjects. In 1959, Imogen applied for a Guggenheim Foundation grant to photograph certain writers in their environments; but her proposal was denied. Imogen set out for Europe on an itinerary that included Berlin, Munich, Paris and London. Many of her last works, throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, were new experiments and explorations. Imogen reapplied for a Guggenheim grant in 1970. This time, she was successful. While inventorying her life’s work, she had rediscovered a cache of her earliest glass-plate negatives, including the nudes of her husband in 1915 on Mount Rainier. Shortly before publication of her book “After Ninety”, on 23/6/1976 she passed away at the age of 93.

Info: Curator: Celina Lunsford, Fenimore Art Museum, 5798 State Highway 80, Cooperstown, New York, Duration: 11/8-15/10/18, Days & Hours: Daily 10:00-17:00 (from Oct 9, Tue-sun 10:00-16:00), www.fenimoreartmuseum.org