ART-PRESENTATION: Art Basel 2018-Unlimited, Part II

Every year at Art Basel the Unlimited Sector is a unique platform for large-scale projects, and provides it’s curator in close cooperation with the participating galeries with the opportunity to showcase installations, monumental sculptures, video projections, wall paintings, photographic series and performance art that transcend the traditional art-fair stand. Really is the most interesting sector of Art Basel, because the visitor can see many young or older artists, and their artworks create the most meaningful and successful dialogue on contemporary social and political issues. It’s really an Unlimited path, since so many artists are involved. Through this artistic journey of 72 premier artworks, we created our own path with artworks that we have distinguished and present them to you in two parts (Part I).

Every year at Art Basel the Unlimited Sector is a unique platform for large-scale projects, and provides it’s curator in close cooperation with the participating galeries with the opportunity to showcase installations, monumental sculptures, video projections, wall paintings, photographic series and performance art that transcend the traditional art-fair stand. Really is the most interesting sector of Art Basel, because the visitor can see many young or older artists, and their artworks create the most meaningful and successful dialogue on contemporary social and political issues. It’s really an Unlimited path, since so many artists are involved. Through this artistic journey of 72 premier artworks, we created our own path with artworks that we have distinguished and present them to you in two parts (Part I).

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Art Basel Archive

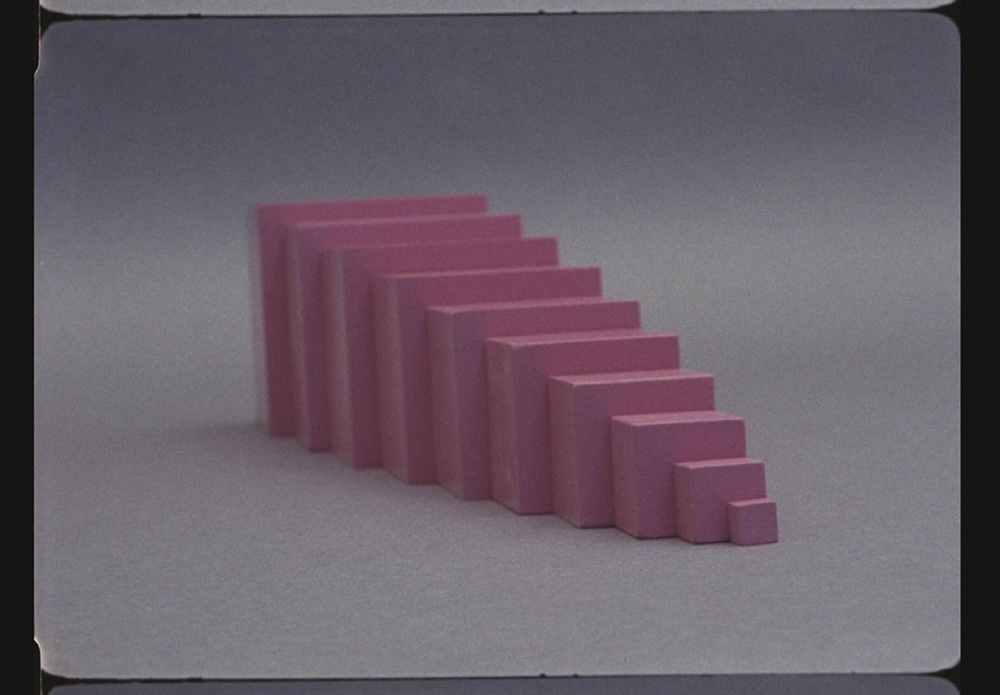

Rashid Johnson’s “Antoine’s Organ” (2016) plays on the structure of the grid and the form’s associations with containment, rigor, and organization. Building upon these constraints as it subverts them, Rashid Johnson’s latticed construction teems with a lively bricolage of potted plants, shea-butter busts, video monitors playing looped films, ornate rugs, music, carefully selected stacks of books and a fully functioning piano. Johnson’s soaring sculptural installation functions through organic accumulation, growth and the delight of unexpected elements meeting. At the beating heart of the labyrinthine work is an upright piano, partially concealed above the viewer and behind the leaves. Created in response to the exponential proliferation of mass shootings in the United States, Robert Longo’s “Death Star II” (2017-18) consists of a suspended globe studded with 40,000 copper and bronze full metal jacket bullets. The work is a sequel to Longo’s original 1993 sculpture “Death Star”, though more than twice as large and housing more than double the number of bullets, reflecting the frightening increase in mass shooting incidents in the United States in the last 25 years. Densely packed over the entire sphere, the gleaming bullets viscerally visualize the physical, material elements enacting this disturbing violence – tragically becoming increasingly ubiquitous. This aggressive, provocative surface in combination with the sculpture’s huge In order to support efforts to reduce gun violence, 20% of the proceeds from the sale of “Death Star II” will be donated to Everytown for Gun Safety. For “Non-Orientable Nkansa II” (2017) Ibrahim Mahama produced hundreds of ‘shoemaker boxes’ with several collaborators, one of whom was named Nkansa. These small wooden objects are made from scrap materials found in Accra and Kumasi, Ghana, and used to contain tools for polishing and repairing shoes. Bearing the marks of the trade of ‘shoeshine boys,’ the boxes also function as an improvised drum, when pounded to solicit business. Mahama and his collaborators (migrant workers from rural Ghana) obtained these items through a process of negotiation and exchange. Such transactions form a critical feature of the artist’s practice, as does the particular site of the work’s production, in this case, a former state-run paint factory. The production location lends added resonance, since it is in the political exigencies of space and the evolution of materials from one context to another that the work’s intention resides. Gathered together in a single, monumental unit, the containers are crammed with other re-purposed items such as heels, hammers and needles, all of which are part of Mahama’s ongoing inquiry into the life of materials and their dynamic potential. In the turbulent summer of 1966, Yto Barrada’s mother, a 23-year-old Moroccan student, was one of 50 ‘Young African Leaders’ invited on a State Department–sponsored tour of the USA. Through play, poetry, and humor, the film “Tree Identification for Beginners” (2017) examines this stage-managed encounter between North America and Africa, and the nascent spirit of disobedience (the Pan-African, Tricontinental, Black Power, and anti-Vietnam war movements) that would come to define a generation. The film brings together 16mm stop-motion animation of Montessori educational toys with voiceovers from Barrada’s mother and other Crossroads Africa participants, as well as historic figures such as Civil Rights activist Stokely Carmichael. The audio effects were created by Barrada and professional artists using noise-making tools in a sound studio. Tree Identification for Beginners also embodies Barrada’s research into form, abstraction, and spatial organization; the installation includes curtains hand-stitched with Montessori grammatical symbols and dyed with pre-industrial colors. Frank Bowling’s “False Start” (1970) is a monumental painting from the artist’s series known as the “Map Paintings” (1967–1971). The work is composed of stained whites, peaches, and pinks under which Bowling stenciled the outlines of continental forms of the Southern Hemisphere: Africa, Australia, and South America. In obscuring Europe and North America, the artist counters a Western-dominated art historical narrative, while drawing attention to the footprints of colonialism and imperialism. During Bowling’s early experiments in pouring and spreading thinned acrylic, the shadows cast though his studio window inspired him to create fluid abstract shapes on the canvas. Noticing a particular shadow assumed the rough shape of South America, he had discovered a motif that served his formal purposes and personal narrative. Carol Bove is known for creating assemblages that combine found and made elements. Incorporating a wide range of domestic, industrial, and natural objects, her sculptures, paintings, and prints reveal the poetry of their materials. “No Title” (2018) relates to Bove’s recent series of “Collage sculptures begun in 2016, which merge various types of sculptural processes utilized in her earlier works and references to art-historical precedents. To create the present work, that is the largest sculpture in Bove’s oeuvre to date, 12-inch square stainless steel tubing that has been crushed and shaped at her studio is arranged with found scrap metals and punctuated with a shallow steel cylinder. Elements of the assemblage are painted in a luminous color, rendering its appearance lightweight and improvisational, as if made by clay or fabric, despite its monumental scale. Camille Henrot’s latest film “Saturday” (2017) focuses on the Seventh-day Adventist (SDA) Church, a Christian denomination that celebrates the Sabbath and practices baptism by immersion. Shot mostly in 3D, the film combines scenes recorded at SDA Church sites in the United States and Polynesia with sundry images of food, surfing, and medical tests; together, they create the impression of a parallel world of hope and belief. Meanwhile, a series of news-ticker-style texts scroll across the screen, visualizing a sense of information inundation. In Daniel Buren’s “Una cosa tira l’altra” (2015-)18 the contrasting stripes delineate an aerial walkway that offers new observational perspectives of the works exhibited, creating not only a new way of moving around in the space but also unexpected viewpoints from within it. Daniel’s artistic intent is to make the context of the work: the space and the light, visible to the spectator, but also to stir the consciousness of the viewer and to create awareness in as broad a sense as possible. Buren’s work redefines the place where the artwork is situated, demonstrating its complexity and his ideological approach to art and every form of experience. The installation “The Tip of the Iceberg” (1991) by Barbara Bloom gives the impression of being underwater or in outer space. A circular table, lit from below and above, is stacked with porcelain tableware, all bearing the logo of the legendary RMS Titanic. Upon approaching the table, it is gradually revealed that the undersides of the dishes are printed with images from the Titanic wreck on the ocean floor. Above, a domed ceiling is surrounded by a frieze of carved objects, copies of waste listed by NASA as being lost or discarded in outer space. Most of the junk orbiting the earth is the result of satellite explosions, though there are also tools like hammers or flashlights dropped by astronauts. The familiarity of the objects in the two debris fields, combined with their astounding inaccessibility, create a powerful sense of physical absence. Bloom is infatuated with the stories objects are able to tell. Her conceptual practice is often centered on installation. He Xiangyu in “Untitled” (2018) refers to the one-child policy, which was first implemented in the late 1970s and ended in 2015, has been one of the most controversial policies in modern Chinese history. With its profound impact on China’s education system, resource allocation and social structure, for those who were born in the 1980s, the far-reaching policy was closely associated with their self and social identities. The “only” child’ thus became a term to both define and differentiate the social generation. The small photo is of the artist himself as a child, installed at his corresponding height. The 3,500 grams of pure gold on the wall adjacent serves as a metaphor and provocation. The irresistible temptations of the glittering, precious metal versus its cheap, everyday mold (the egg carton) acts as the perfect portrait of a conflicted generation defined by power vs powerlessness, materiality vs conceit. The lone egg sits on a golden throne: In this new context the relationship between the egg-tray and the egg is reversed. Douglas Gordon’s film “I had nowhere to go: Portrait of a displaced person” (2016), is an intimate portrait of the godfather of American Avant-Garde cinema’ Jonas Mekas – and, at 95 years old, among the remaining few to have escaped and survived Nazi persecution. The film has been celebrated for its sparse materiality, and its reflection on the narrative of history. Douglas Gordon’s film work has redefined expectations of the relationship between sound, text, time, and the moving image. “I had nowhere to go” collates one minute of film time with each year of Mekas’s momentous life, including his journey from a forced labor camp and a displaced persons center during WWII, and his emigration from Lithuania to New York. The viewer is plunged into collective and individual spaces of memory via long, imageless stretches over which Mekas narrates excerpts from his memoir (from which the film takes its title). With an immersive sound environment and intermittent, fleeting images that stand in evocative juxtaposition to Mekas’s anecdotes, Gordon’s film reveals in its subject a puckish humor that outweighs despair, and an unabated curiosity for life that both illuminates and softens the sadness of his subject matter.