ART-PRESNENTATION: Art Basel 2018-Unlimited,Part I

Every year at Art Basel the Unlimited Sector is a unique platform for large-scale projects, and provides it’s curator in close cooperation with the participating galeries with the opportunity to showcase installations, monumental sculptures, video projections, wall paintings, photographic series and performance art that transcend the traditional art-fair stand. Really is the most interesting sector of Art Basel, because the visitor can see many young or older artists, and their artworks create the most meaningful and successful dialogue on contemporary social and political issues. It’s really an Unlimited path, since so many artists are involved. Through this artistic journey of 72 premier artworks, we created our own path with artworks that we have distinguished and present them to you in two parts.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Art Basel Archive

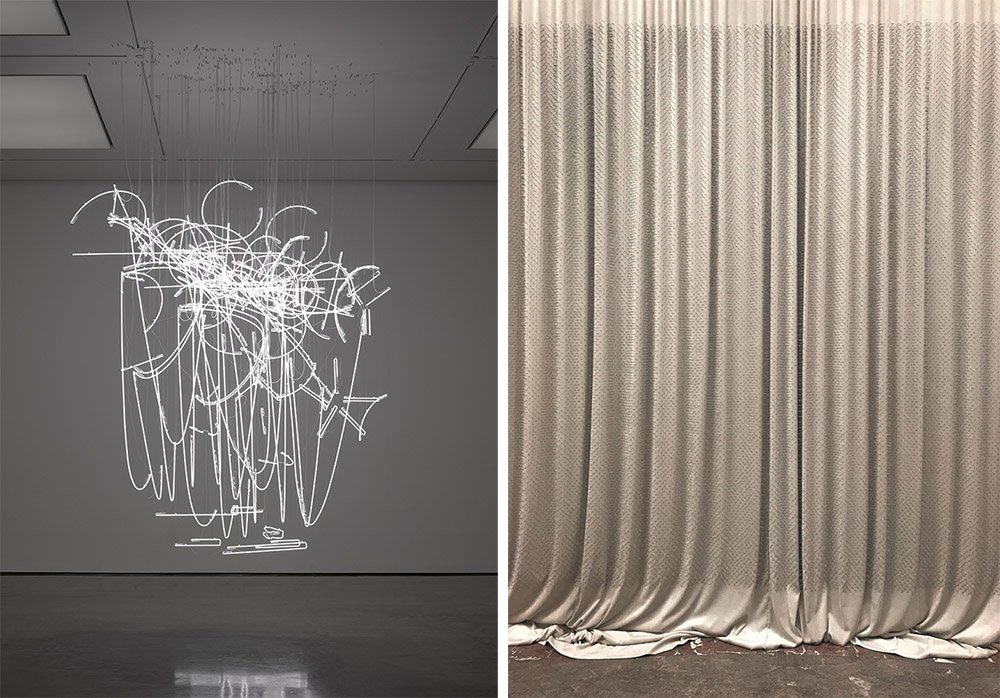

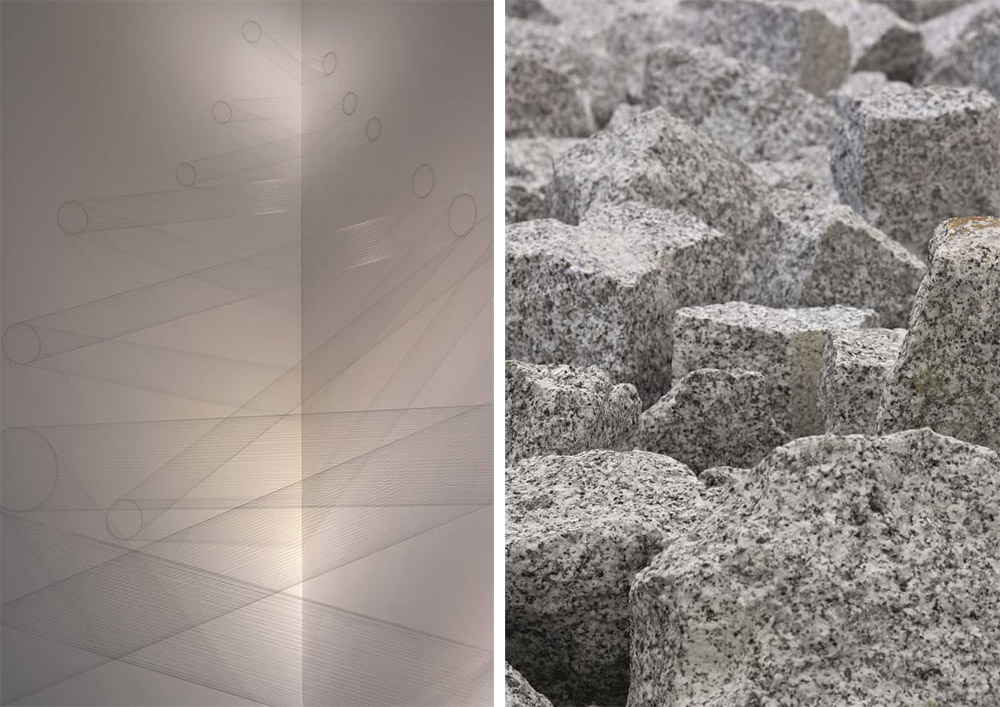

Viewer participation and collaboration has been and remains central to the tenets of Yoko Ono’s practice. By inviting the viewer to actively become a part of “Mend Piece’’ (1966-2018), the audience helps to create meaning in each piece. The installation that has been shown in a number of Ono’s retrospectives, is one of her first and thus seminal of her participation works and was originally created in 1966. The work is composed of fragments of broken cups placed on a table for the audience to mend with tape, string, glue, or other materials. After mending, the viewer places the cup on shelves in an all-white room, reminiscent of a dream. The metaphor of mending and healing are close. In Ono’s words: “As you mend the cup, mending that is needed elsewhere in the Universe gets done as well. Be aware of it as you mend”. At a time of global socio-political crisis Kostis Velonis’s large-scale sculpture titled “How to Build Democracy Making Rhetorical Comments (after Klutsis’ design for propaganda kiosk, screen and loud speaker, platform, 1922)” (2009) is more timely than ever. The interactive sculpture is a reconstruction of one of the designs by the Latvian Constructivist Gustav Klutsis for agitprop kiosks, whereas Velonis’s kiosk is a propagandistic machine for freedom of expression and self-determination. This is the first presentation of the work after its exhibition at Velonis’s solo show at the Kunstverein in Hamburg titled “How One Can Think Freely in the Shadow of a Temple” in 2009. His recent shows include, among others, Documenta 14 and a solo exhibition organized by NEON (as part of ‘City Project,’ Athens). Symbolizing iconoclasm yet also acting as an accolade, the 3,020 broken porcelain vessels that comprise “Tiger, Tiger, Tiger” (2015) speak of a multitude of creators who once touched them. Gathered by Ai Weiwei over the course of two decades, each fragment depicts a hand-painted tiger that adorned the inside base of a precious bowl. The porcelain originates from the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) and each tiger reveals the hand of a now-forgotten artist. Placed next to one another on a simple white platform, the shards become a visually unified sea of history. The tiger is also a zodiac sign and symbol of courage in China, and in Ai Weiwei’s work it becomes a metaphor for both the endurance of cultural memory, and, in this fractured state, its fragility. Cerith Wyn Evans’s “Neon Forms (after Noh I)” takes form through the reflection on and interrogation of our notions of reality and cognition, perception and subjectivity. This work is the first in a series of seminal “neon drawings” the artist conceived in 2015. Taking inspiration from the choreology and codified, precise movements of traditional Japanese Noh theater, the work lyrically maps the notations inherent to movement, giving rise to their physical form. Edith Dekyndt’s installation “They Shoot Horses (Part One)” (2017) consists of a long velvet curtain pierced at regular intervals by steel nails and a video showing archival footage of a 1930s dance marathon. The title refers to Horace McCoy’s Depression-era novel “They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?”, which achieved broader fame with Sidney Pollack’s film adaption in 1969. The film remains one of the more poignant portraits of the grueling disparities of society and desperation of the working class during the Great Depression in America. Dan Graham’s pavilion “S-Curve for St. Gallen” (2001) was conceived for the yard of the locomotive shed in St. Gallen, Switzerland, where it served as museum café. Oscillating between installation and quasi-functional space, the work is informed by a social awareness that is typical of Graham’s work. Rigorously conceptual, uniquely beautiful, and avowedly public, the pavilions exhibit a deliberate disorientation and playfulness that Graham encourages. Blurring the line between art and architecture, his pavilions are comprised of stainless steel and two-way mirror glass to create diverse optical effects. The transparent but reflective walls produce a distorted reflection: The viewer becomes involved in the voyeuristic act of seeing oneself, while at the same time watching others – playing with physical reality and reflections, creating light-hearted situations out of a surveillance culture. In 1978, Pape began to experiment with a group of her students, tying strings around trees and weaving them through the natural environment of the Parque Lage Gardens in Rio de Janeiro. These experiments mark the beginning of the “Ttéias” that continue to demonstrate Pape’s enduring interest in spatial investigations. Constructed by the geometric installation of gold threads “Ttéia 1, B” (2000-2018) delineates volumes and achieve visually powerful effects, charging the space with a sense of the indefinable, the immaterial. The groups of thread are also staggered, intersecting or merely appearing to intersect, a blend of the real and the imaginary. The word ‘ttéia,’ which Pape coined, is an elision of the Portuguese word for “web” and “teteia” a colloquial word for a graceful and delicate person or thing. “Ivory Granite Line” (2016) by Richard Long evokes horizon lines, manmade trails, ancient boundary lines and geographical borders. Formed of closely situated but unevenly shaped rocks, meaning that the density is uniform even while the raw components are not, the work changes each time the organic objects are arranged, according to the artist’s instruction and placement. While this work is made of granite sourced from a quarry in Spain, stone in all its guises remains one of Long’s preferred materials. By bringing in raw matter from the outside world – asserting an alternately ancient and contemporary relationship to the land, redolent of prehistoric monuments and current environmental concerns alike. The setting in which 15 of the 100 existent drawings of Andra Ursuta’s “The Man From The Internet” (2017) are shown is a makeshift trailer similar to the vehicles filled with dead refugees occasionally abandoned on international highways, pointing to the endless return of unresolved cycles of violence, colonialism, and nationalism that haunt the present and the history of civilization. The work consists of unique versions of the image of an unknown dead man, rendered painstakingly over a period of 10 years. It acts both as a monument to the fragility of individual life when confronted with history and as a solipsistic echo chamber for the creepy obsession with the death of a stranger. The source image is from a website documenting crimes of the Russian army during the Chechen wars of the 1990s. Nothing about the image confirms the provenance of the body: It could just as easily document Chechen atrocities against Russians or almost any conflict in the world, it is an image file, not an image. José Yaque’s “TUMBA ABIERTA III” (2018) is a type of transforming archive in which we see how many natural elements, in their infinite variety (plants, seeds, fruits, leaves), are transmuted through time, and in which the important fact is not losing or gaining new qualities but showing the permanent change of things. The work is an invitation to see the intrinsic beauty of the constant transfiguration that is also real in ourselves. In 2010, Bangkok erupted in violence with protesters from both the Left and Right, battling the military in the streets. The main weapon on both sides was the tire, both as a barricade and as improvised Molotov cocktail, rolled instead of thrown. In 2015, Rirkrit Tiravanija created an installation, “untitled 2015 (bangkok boogie woogie, no. 1)”, sourced from this particularly vernacular form of action, straight from the streets of his hometown. In what became the very last action at the old Gavin Brown’s enterprise space on Greenwich St. in New York before it was demolished, Tiravanija cast rubber tires into bronze doppelgängers, and rolled them flaming through the gallery filled with petroleum fuel; all of this was filmed, edited, and used as the backdrop for the installation. The mirrored copper floor reflects the rolling burning movement, while the metal tires produce a clanging soundtrack, conjuring a feeling of violent assault within the gallery space.