ART-PRESENTATION:Ai Weiwei-Fan Tan

Drawing his inspiration from Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol. Ai Weiwei’s Works are able to challenge our societies with such force through his transformation of everyday objects into works of art. Ai Weiwei is the son of Ai Qing (1910-1996), the famous Chinese poet who discovered the West in 1929 on disembarking at Marseille, on the docks of La Joliette, precisely the spot where the Mucem is located today.

Drawing his inspiration from Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol. Ai Weiwei’s Works are able to challenge our societies with such force through his transformation of everyday objects into works of art. Ai Weiwei is the son of Ai Qing (1910-1996), the famous Chinese poet who discovered the West in 1929 on disembarking at Marseille, on the docks of La Joliette, precisely the spot where the Mucem is located today.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Mucem Archive

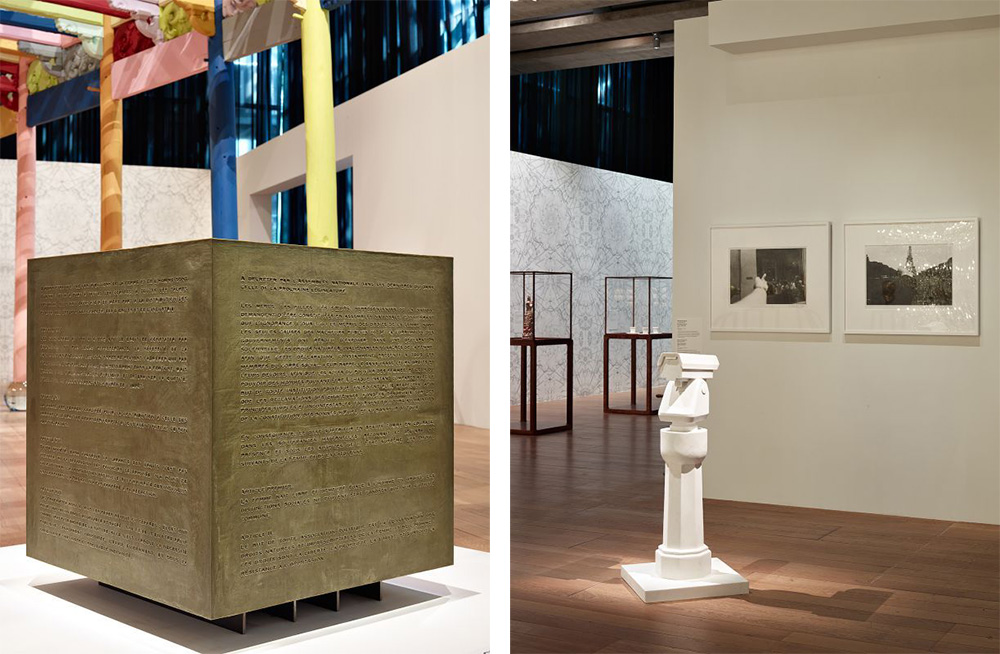

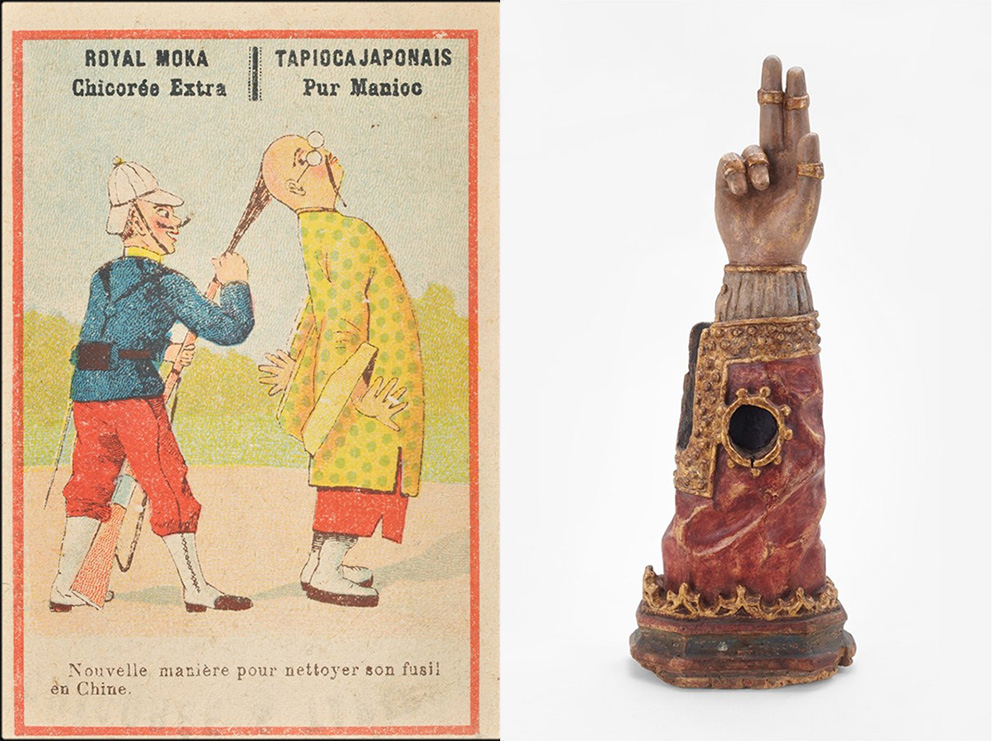

Ai Weiwei’s connection with Marseille motivated the artist to take us on a voyage through time and art, which he links back to his paternal lineage. Through the new resonances that emerge from his exhibition “Fan Tan” at Mucem in Marseille, we are able to view Ai Weiwei’s work in a new light. Fifty artworks, 2 of which are new creations, are placed in parallel with fifty objects from the Mucem’s Collections invite us to question opposing notions such as East and West, original and copy, art and craft, destruction and conservation. The choice of the title “Fan-Tan”, symbolizes the chaotic relations between France and China at the end of the 19th Century and the beginning of the 20th Century. The title refers both to an English army tank which operated on French soil during the WWI. It had been donated by a Chinese businessman as part of the war effort. It was decorated with an eye on each side, the same eye that featured on certain Chinese boats. It was painted by volunteer workers from the Chinese forces who also contributed to the war effort in England and France. For the Chinese, “Fan-Tan” is also the name of a local betting game comparable to roulette. At the entrance to the exhibition, is a wooden structure from the Ming dynasty period of a traditional house. As with all the Chinese wooden constructions chosen by Ai Weiwei, the focus is on the skill of the craftsmen who, thanks to ancient knowledge, built these structures that can be assembled and dismantled with ease. This work, entitled “Colored House”, is also a testament to a China on the verge of extinction, in a society where industrialization on a vast scale has a tendency to erase the past. The house is covered with a coat of brightly coloured industrial paint. The ancient covered up by the new. The breathing wood here is covered by an impermeable synthetic material. The monumental structure rests on glass feet, a symbol of the apparent extreme fragility of a huge construction. In 1929 Ai Qing disembarked at the port of Marseille, specifically at La Joliette, near the Mucem. It seems to have had a powerful impact on him for in 1932 he wrote a poem describing the chaotic, teeming quality of the city and its port. A group of objects retraces Ai Qing’s arrival in Marseille: the model of an ocean liner similar to the one he took to travel to France, as well as the captain’s log book, on which he made this journey. Ai Weiwei in 1981 he travelled to the United States, eventually settling in New York where he would stay until 1993. It was there that he assimilated the theories of Marcel Duchamp. It was in this period that he would go on to create his first objects that could be classified as ready-made. These objects were known from publications, but here they are presented for the first time in the context of an exhibition. They adhere to the principle of recycling everyday objects with the aim of giving expression to a situation. In the second exhibition space the wallpaper covering the entirety of the long wall on the right-hand side is composed of a clever combination of images merging the Twitter logo, surveillance cameras, rebar and handcuffs, as though seen through a kaleidoscope. This clearly refers to Ai Weiwei’s freedom of speech on social networks, but it also specifically refers to the 81-day period of detention the artist endured in the spring of 2011, followed by a period under surveillance at his home in China. The work is entitled “The Plain Version of the Animal that Looks Like a Llama but is Really an Alpaca”. The word “alpaca”, pronounced in a certain way in China, clearly corresponds to an insult which would be the equivalent of “fuck your mother” in English: a gesture designed to provoke the propaganda authorities who muzzle the social networks in China. The series of photos entitled “Study of Perspective” consists of him giving the finger to various monuments and landmarks symbolizing political and cultural power. He has also created the sculpture “Up Yours” (2017) that isolates the arm and repeats the gesture. Ai Weiwei has conceived a new work made from Marseille soap especially for this exhibition, manufactured according to the rules of the Marseille soap-making art. The texts incrusted in the substance illustrate certain interests of his, namely the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. In the third and final space of the exhibition is on presentation “Chandelier”, for the work the artist decided to suspend a series of chandeliers originally created in the 1920 and 30s in both France and Germany. This new work constitutes a kind of superlative glitz, evoking the chandeliers that can be seen today in the large hotels in all Chinese megacities. In order to evoke the history of Franco-Chinese relations at the turn of the 19th and 20th Centuries that Ai Weiwei conceived “Circle of Animals” (2012) it consists of replicas of a series of 12 animal sculptures illustrating the signs of the Chinese zodiac, which were found at the residence of the Chinese emperor Yuamingyuan. This place may have been conceived as a Taoist paradise, but the fountain-clock animated by the twelve animal figures was designed by Father Castiglione and Father Benoît, two Jesuit priests who served in the court of the emperor Qian Long. During the Second Opium War in 1860 they were plundered by the Western troops. Here, Ai Weiwei is referring to a controversial issue: in 2009 two of these animal heads were put up for sale, since they were then part of the collection belonging to Pierre Bergé and Yves Saint Laurent, which sparked an international controversy. They have since been offered by the Kering group to the Chinese State. This piece examines the practice of making replicas – a practice that has long been conducted in China – but also the celebration of historical feats, looting, and the nature of property rights.

Info: Curator: Judith Benhamou-Huet, Mucem, 1 esplanade du J4, Marseille, Duration: 20/6-12/11/18, Days & Hours: From 20/6-6/7 & 3/9-4/11: Mon & Wed-Sun 11:00-19:00, From 7/7-2/9 Mon & Wed-Sun: 10:00-10:0 (August daily), From 5/11-30/4 Mon & Wed-Sun” 11:00-18:00, www.mucem.org