ART-PRESENTATION: Gordon Matta Clark-Anarchitect

Encouraged by his father, a trained architect who briefly worked under Le Corbusier, Gordon Matta-Clark attended Cornell University School of Architecture, graduating in 1968. After he returned to New York City in 1969, he began developing a series of site-specific artworks and actions, repurposing his architectural training in methods that called into question basic assumptions and premises of architecture.

Encouraged by his father, a trained architect who briefly worked under Le Corbusier, Gordon Matta-Clark attended Cornell University School of Architecture, graduating in 1968. After he returned to New York City in 1969, he began developing a series of site-specific artworks and actions, repurposing his architectural training in methods that called into question basic assumptions and premises of architecture.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Jeu de Paume Archive

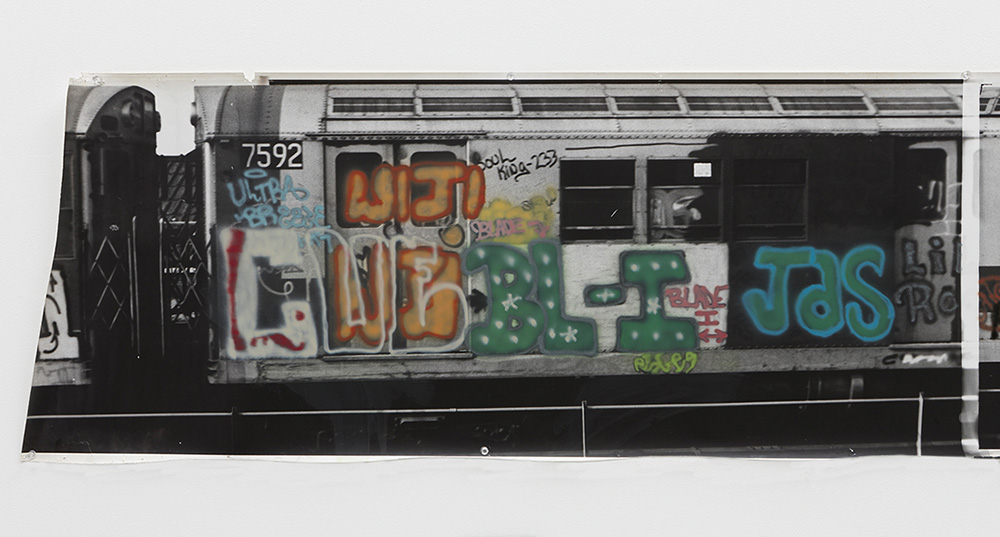

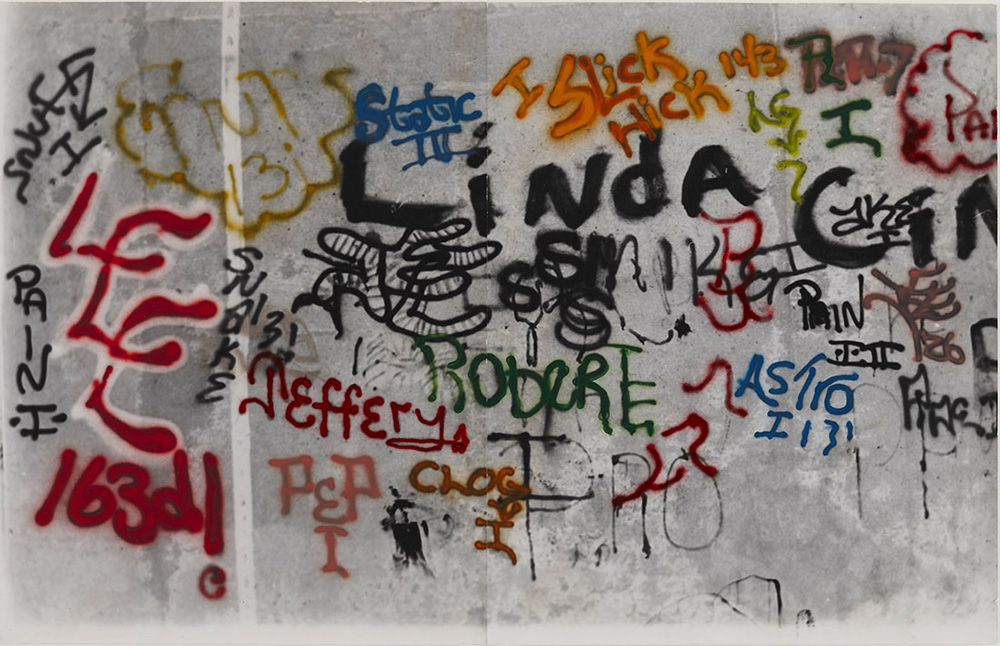

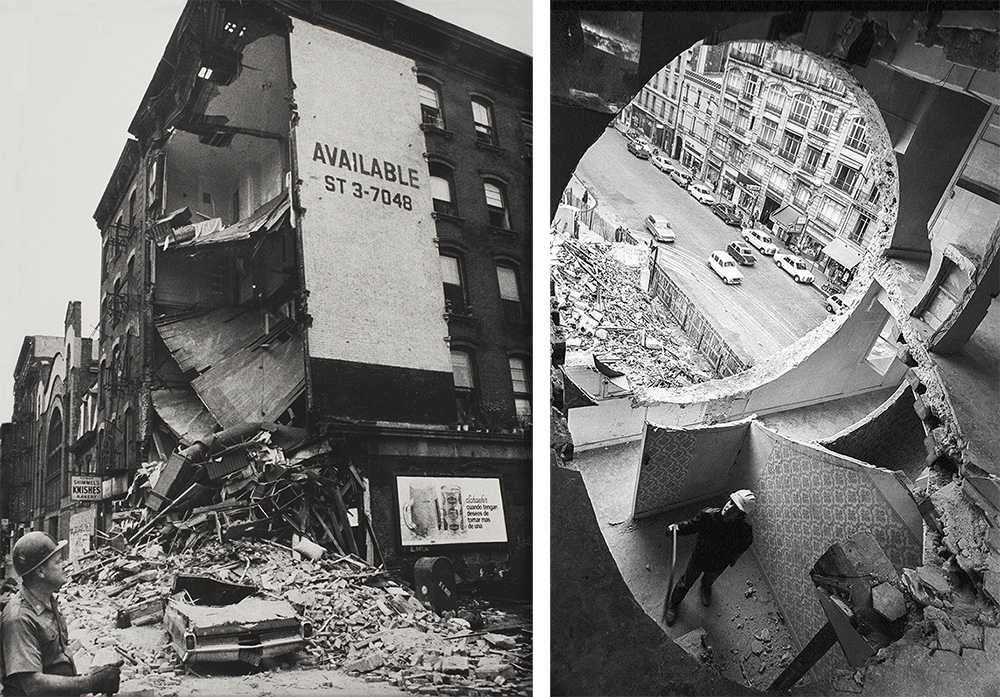

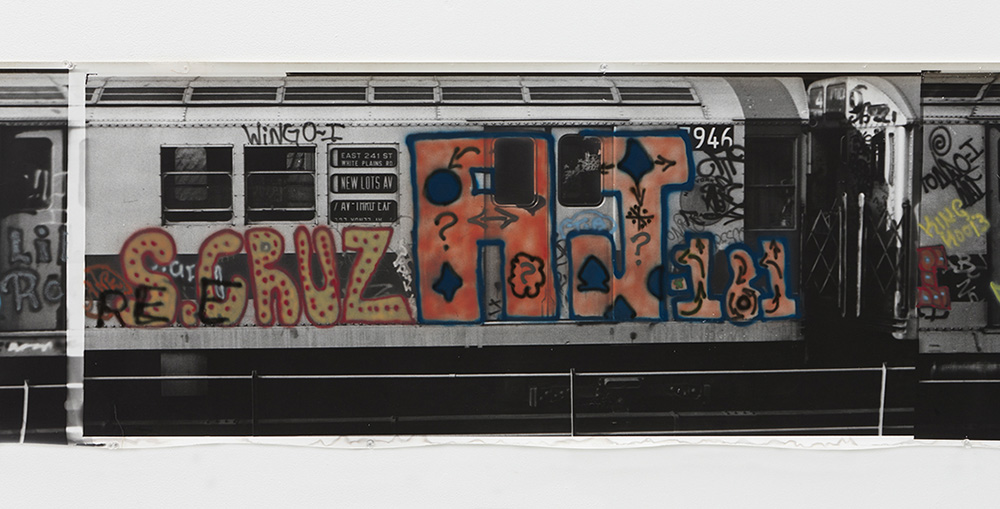

Featuring 100 works by Gordon Matta-Clark, the exhibition “Anarchitect” explores the importance of Matta-Clark’s practice towards a rethinking of architecture after modernism. Embracing a diversity of media that include photography, film and printmaking, the exhibition features a number of works related to contemporary urban culture that further contextualize Gordon Matta-Clark’s compelling critique of architecture. An important part of Gordon Matta-Clark’s actions were realized in the South Bronx during a period marked by the borough’s steep economic decline prompted in great part by the massive exodus of its middle class to suburbia. As a consequence, a great number of abandoned buildings in the area provided raw material for Matta-Clark to intervene on. One of the most iconic series from this period, “Bronx Floors” became emblematic of Matta-Clark’s practice and was later expanded into highly ambitious works such as “Conical Intersect”, next to the soon-to-be opened Centre Pompidou. “Walls/Wallspaper” (1972): Matta-Clark cast a hopeful, constructive eye over the derelict buildings he found around the Bronx, and was struck by what remained of partially demolished buildings. In a series of photographs Matta-Clark captured the remnants of interior walls turned exterior through incomplete demolition. Like an urban archeologist he captured these remnants of bygone habitation, peeling paint and residual wallpaper, evidence of the structure as “home”. To evolve this work beyond documentation, he then printed the images on a newspaper off-set press adding watercolor tones and hung these replications in a massive floor-to ceiling installation at 112 Greene Street called “Wallspaper”. The installation also included a stack of newspaper handouts that viewers were allowed to take away. These handouts were made of individual sheets of newspaper, each presenting one obsolescence photograph of the Bronx walls on either side. The take away piece invited the audience to hang this wall from the South Bronx on their own wall at home, reflecting the fragility of such spaces in an era of disastrous urban planning. In 1973 Matta-Clark published a small artist’s book titled “Wallspaper” in which he reproduced the colored prints that he had made from the original black and white photographs. “Bronx Floors” (1975-73): After graduating from Cornell University School of Architecture in 1968, Gordon Matta-Clark returned to New York where he continued his art practice experimenting with space and materials. A major breakthrough happened in 1972, when he came to the South Bronx to perform geometrical cuts onto the structure of abandoned buildings. This series, with its mix of performance bravado, photography and sculpture, was produced for the most part in buildings on Boston Road, in the Morrisania neighborhood. “Graffiti” (197-73Matta-Clark also paid tribute to the nascent graffiti culture that was fast transforming the urban landscape of New York City under the guise of a gigantic, communal artwork that rendered the built environment trapped in language. In the summer of 1973, he submitted a proposal to exhibit his hand-colored photographs of graffiti at the Washington Square Art Fair. Having his proposal denied, he decided to set up his own protest art fair where he would exhibit his graffiti photoglyphs on the street mounted on sawhorses. In preparation he took his truck to the South Bronx and invited local artists to cover it completely with graffiti. He parked the truck alongside his protest exhibition and offered to sell it in pieces, using a blowtorch to cut out a sections right there on the street when someone expressed interest. Created for the 9th Paris Biennale, “Conical Intersect” (1975) coincided with a daunting process of urban interventions in Paris that entailed a reorientation of circulation flows, new housing developments, and the revitalization of the city’s historic center. The work consisted of a cone hollowed out of two derelict 17th Century buildings next to the site where the glaring, industrial-looking structure of the future Centre Pompidou was rising amid the medieval an prerevolutionary buildings in the very center of Paris. “This old couple” Matta-Clark noted, “was literally the last of a vast neighborhood of buildings destroyed to ‘improve’ the Les Halles–Plateau Beaubourg area”. A traditional marketplace since the middle ages, Les Halles became the city’s commercial core in the early 19th Century. Its destruction was highly controversial and both the left and the right criticized Matta-Clark for his participation in and critique of this “urban renewal”. The design of the cut was inspired by Anthony McCall’s “Line Describing A Cone” (1973) and can also be seen as a para-cinematic work: the cone shape functioning as a kind of lens looking down from the new Beaubourg (the future) through the derelict cut buildings (the past) and opening up onto the everyday street scene (the present). Sited in an abandoned pier on the Hudson River across from a section of the West Side Elevated Highway that had collapsed the year before, “Day’s End” (1975) is Gordon Matta-Clark’s most ambitious site-specific work in New York City. Experimental artist G. H. Hovagimyan, who assisted Matta-Clark in the creation of “Day’s End” stressed the work’s guerilla/anarchist dimension that conveyed “A sense of revolutionary barricades evocative of the Paris Commune in the construction of the barrier pile of timbers”. Matta-Clark undertook this project without filing for permission, and while New York City officials did not take notice of his activity during its creation, the police showed up at the opening event having read about it in a newspaper article. A police investigation was open while Matta-Clark went to France for the project “Conical Intersect” and he stayed abroad while his lawyer tried to convince the authorities it was art, not vandalism. Eventually the pending lawsuit was dropped so he could return to the United States safely. “Garbage Wall” (1970-2018) is emblematic of the focus Gordon Matta-Clark placed early on in his career, architecture, activism, and citizen engagement. The work was originally conceived as a four-day performance that took place outside St. Mark’s Church in the East Village. In the following year, while scouting locations for his contribution to the site-specific exhibition Brooklyn Bridge Event, he spotted an elaborate living space constructed by a homeless person for shelter and built from discarded materials, including a rudimentary stove and washing basin. Thinking that his architectural training could be used to find sustainable forms of shelter, he reconfigured his “Garbage Wall” as a building element that could be made quickly and inexpensively by anyone. An iteration of this project is on presentation at the Jeu de Paume during the exhibition. “Food” was conceived as a work of art, from the design of its interior and the special Sunday menus curated by artists (Donald Judd, Keith Sonnier, and Yvonne Rainer, among others) to the films he produced of meal preparations and service. A place where artists met and discussed ideas, had an inexpensive meal, and found paid jobs to support their own work. Like art-making, consuming food was for Matta- Clark an act of transformation, through which the body digests and incorporates processes and products. Towards the end of his career, Gordon Matta-Clark focused his energy on empowering residents to take ownership of their neighborhoods. To ensure that his efforts had longevity, he designed two socially integrative projects, including an unrealized art center in the South Bronx and a Resource Center and Environmental Youth Program for Loisaida, for which he was awarded a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship in 1977, had the goal of training participants to become employable professionals, stressing the artist’s desire to transform the area through its own positive efforts. Sadly, Matta-Clark was only able to help them build a few concrete columns on an empty lot and initiate the cleanup of the building’s storefront before his untimely death from pancreatic cancer on 26/81978.

Info: Jeu de Paume, 1 place de la Concorde, Paris, Duration: 5/6-23/9/18, Days & Hours: Tue 11:00-21:00, Wed-Sun 11:00-19:00, www.jeudepaume.org