ARCHITECTURE: Philip Johnson

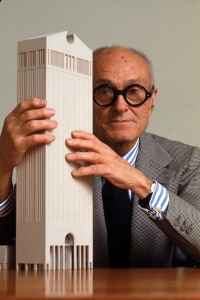

The first Pritzker Architecture Prize was given to Philip Johnson (8/7/1906-25/1/2005), whose work demonstrates a combination of the qualities of talent, vision and commitment that has produced consistent and significant contributions to humanity and the environment. As a critic and historian, he championed the cause of modern architecture and then went on to design some of his greatest buildings.

By Dimitris Lempesis

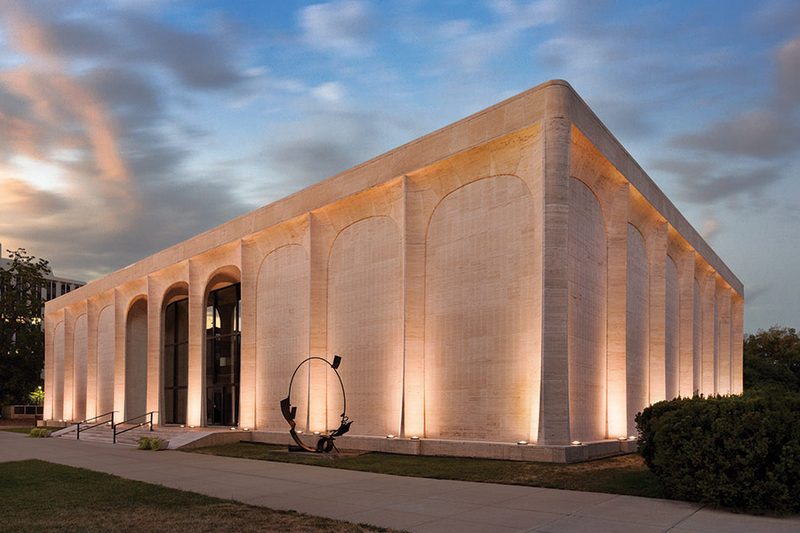

Philip Johnson studied at Harvard University as an undergraduate, where he focused on history and philosophy, particularly the work of the Pre-Socratic philosophers. Johnson interrupted his education with several extended trips to Europe. These trips became the pivotal moment of his education; he visited Chartres, the Parthenon, and many other ancient monuments, becoming increasingly fascinated with architecture. However, the most important moment that changed his entire worldview was in 1928, that time Johnson met with architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who was at the time designing the German Pavilion for the 1929 Barcelona International Exposition. The meeting was a revelation for Johnson and formed the basis for a lifelong relationship of both collaboration and competition. Johnson returned from Germany as a proselytizer for the new architecture. Touring Europe more comprehensively with his friends Alfred H. Barr, Jr. and Henry-Russell Hitchcock to examine firsthand recent trends in architecture, the three assembled their discoveries as the landmark show “The International Style: Architecture Since 1922” at the Museum of Modern Art, in 1932. The show was profoundly influential and is seen as the introduction of modern architecture to the American public. It introduced such pivotal architects as Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, and Mies van der Rohe. The exhibition was also notable for a controversy: architect Frank Lloyd Wright withdrew his entries in pique that he was not more prominently featured. Except that he designed the “Sculpture Garden” of the MoMA, but also and a number of large projects, the one that described him as the most innovative work to date and passed into history, is the “Glass House”, designed as his own residence in Connecticut 1949, where he lived and left his last breath at his 99 years, at 25/1/5. The concept of a Glass House set in a landscape with views as its real “walls” had been developed by many authors in the German Glasarchitektur drawings of the 1920s, and already realized by Johnson’s mentor Mies van der Rohe. It consists of two separate buildings: “Glass House” and “Brick House”. In ”Glass House”, he placed the living room, while in ”Brick House” the bedroom. The first is made of glass and is free furnished and open connecting the interior with the exterior and the public with the private, the second is a brick volume without openings, allowing the free movement of the sexual partners. Johnson with the ”Glass House” overturned stereotypes, that wanted the house-box introduced the free space between the two blocks, opened the house in public-open-external and placed the bedroom away from the controlled interior of the house. Johnson’s architectural work is a balancing act between two dominant trends in post-war American Art: the more “serious” movement of Minimalism, and the more popular movement of Pop Art. His best work has aspects of both movements. Johnson’s personal art collection reflected this dichotomy, as he introduced artists such as Mark Rothko to the Museum of Modern Art as well as Andy Warhol. Straddling between these two camps, his work was seen by purists of either side as always too contaminated or influenced by the other. As an art collector Johnson’s eclectic eye supported avant-garde movements and young artists often before they became widely known. His collection of American art was strong in Abstract expressionism, Pop Art, Minimalism, Neo-Dada, Color Field, Lyrical Abstraction, and Neo-Expressionism and he often donated important works from his collection to institutions like MoMA, and other important private museums and University collections like the Norton Simon Museum, the Sheldon Museum of Art and the Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University among many others.

Philip Johnson studied at Harvard University as an undergraduate, where he focused on history and philosophy, particularly the work of the Pre-Socratic philosophers. Johnson interrupted his education with several extended trips to Europe. These trips became the pivotal moment of his education; he visited Chartres, the Parthenon, and many other ancient monuments, becoming increasingly fascinated with architecture. However, the most important moment that changed his entire worldview was in 1928, that time Johnson met with architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who was at the time designing the German Pavilion for the 1929 Barcelona International Exposition. The meeting was a revelation for Johnson and formed the basis for a lifelong relationship of both collaboration and competition. Johnson returned from Germany as a proselytizer for the new architecture. Touring Europe more comprehensively with his friends Alfred H. Barr, Jr. and Henry-Russell Hitchcock to examine firsthand recent trends in architecture, the three assembled their discoveries as the landmark show “The International Style: Architecture Since 1922” at the Museum of Modern Art, in 1932. The show was profoundly influential and is seen as the introduction of modern architecture to the American public. It introduced such pivotal architects as Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, and Mies van der Rohe. The exhibition was also notable for a controversy: architect Frank Lloyd Wright withdrew his entries in pique that he was not more prominently featured. Except that he designed the “Sculpture Garden” of the MoMA, but also and a number of large projects, the one that described him as the most innovative work to date and passed into history, is the “Glass House”, designed as his own residence in Connecticut 1949, where he lived and left his last breath at his 99 years, at 25/1/5. The concept of a Glass House set in a landscape with views as its real “walls” had been developed by many authors in the German Glasarchitektur drawings of the 1920s, and already realized by Johnson’s mentor Mies van der Rohe. It consists of two separate buildings: “Glass House” and “Brick House”. In ”Glass House”, he placed the living room, while in ”Brick House” the bedroom. The first is made of glass and is free furnished and open connecting the interior with the exterior and the public with the private, the second is a brick volume without openings, allowing the free movement of the sexual partners. Johnson with the ”Glass House” overturned stereotypes, that wanted the house-box introduced the free space between the two blocks, opened the house in public-open-external and placed the bedroom away from the controlled interior of the house. Johnson’s architectural work is a balancing act between two dominant trends in post-war American Art: the more “serious” movement of Minimalism, and the more popular movement of Pop Art. His best work has aspects of both movements. Johnson’s personal art collection reflected this dichotomy, as he introduced artists such as Mark Rothko to the Museum of Modern Art as well as Andy Warhol. Straddling between these two camps, his work was seen by purists of either side as always too contaminated or influenced by the other. As an art collector Johnson’s eclectic eye supported avant-garde movements and young artists often before they became widely known. His collection of American art was strong in Abstract expressionism, Pop Art, Minimalism, Neo-Dada, Color Field, Lyrical Abstraction, and Neo-Expressionism and he often donated important works from his collection to institutions like MoMA, and other important private museums and University collections like the Norton Simon Museum, the Sheldon Museum of Art and the Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University among many others.