PHOTO:Being New Photography 2018

Since its inception in 1985, “New Photography” series of exhibitions at MoMA has introduced more than 100 artists from around the globe, and it is a key component of the Museum’s program. Every two years, “New Photography” presents urgent and compelling ideas in recent photography and photo-based art. This year’s edition, Being, asks how photography can capture what it means to be human.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: MoMA Archive

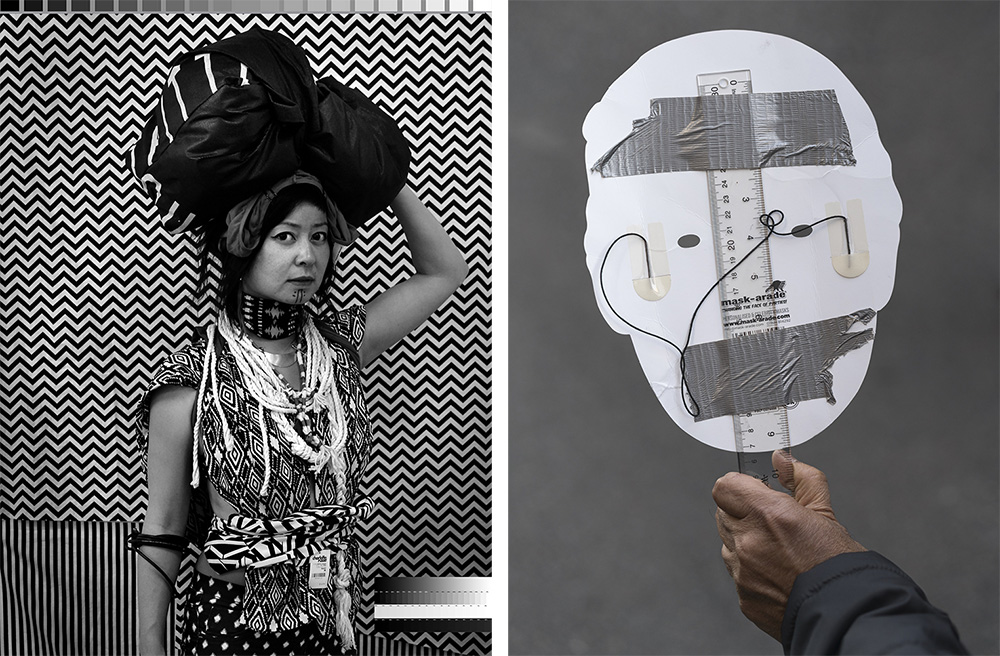

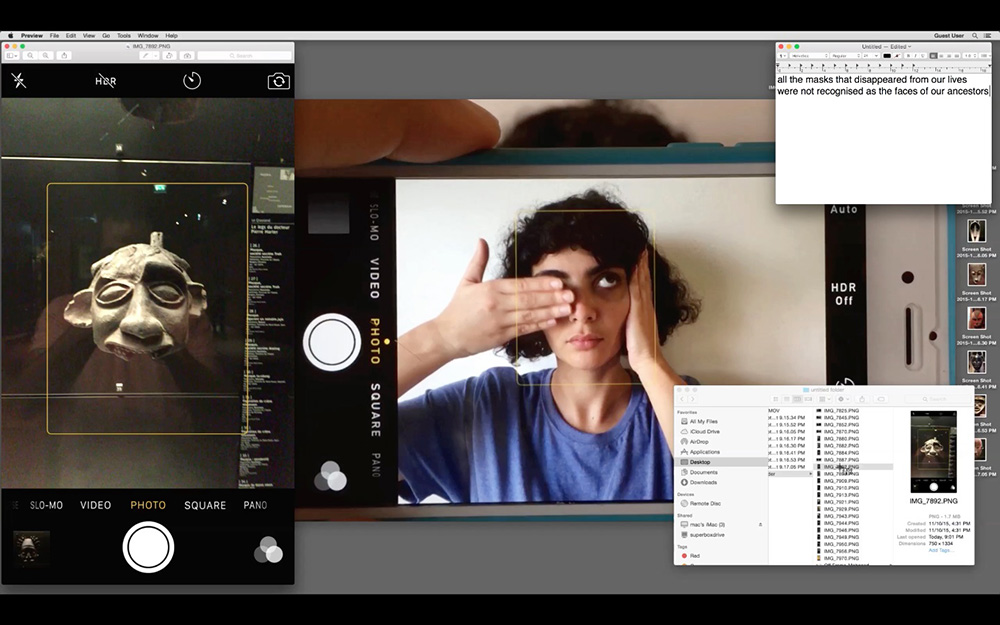

At a time when questions about the rights, responsibilities, and dangers inherent in being represented and in representing others are being debated around the world, the works featured in the exhibition “Being New Photography 2018” call attention to assumptions about how individuals are depicted and perceived. Many challenge the conventions of photographic portraiture, or use tactics such as masking, cropping, or fragmenting to disorient the viewer. In others, snapshots or found images are taken from their original context and placed in a new one to reveal hidden stories. While some of the works might be considered straightforward representations of individuals, others do not include images of the human body at all. Together, they explore how personhood is expressed today, and offer timely perspectives on issues of privacy and exposure; the formation of communities; and gender, heritage, and psychology. Andrzej Steinbach upends familiar tropes from both traditional portraiture and fashion photography. His series “Gesellschaft beginnt mit drei” (2017) uses the conventional format of a group portrait, yet each picture depicts only one figure in full, cropping the others out of the frame and switching the sitters’ positions and clothing throughout the series. Works by Paul Mpagi Sepuya explore the intersections of race, gender, and desire within the history of portrait photography. In his ongoing series “Figures”, “Grounds”, and “Studies”, and in a new collage made for this exhibition, Sepuya uses the materials of the studio itself, making the camera visible, layering multiple pieces of photographic paper, and foregrounding the platform and drapery upon which the model poses to force viewers to confront their own perspectives. Often beginning with a model against a studio backdrop, Aida Muluneh constructs characters through colorful make-up and costume and by doubling figures or limbs. Titled after her grandmother’s saying, “The world is nine; it is never complete and it’s never perfect,” Muluneh’s series “The World Is 9” (2016) conveys the multiplicity and contradictions inherent within an individual. In the series “Cargo Cults and Passport Photos (Migrants)”, Stephanie Syjuco reinterprets standard tropes of 19th-century ethnographic portraiture and the ubiquitous format of passport photography. The “migrants” pictured in her passport photos, for example, have covered their faces, suggesting that making their physical identities known might pose great risk. Carmen Winant’s “My Birth” (2017–18), a site-specific installation for the exhibition, fills two facing walls from floor to ceiling with images of women preparing for and in the process of labor and childbirth. Using images appropriated from books and magazines, Winant explores how these essential activities are often kept hidden even in our image-saturated culture and reflects upon her own birth experience within a web of collected representation. Yazan Khalili’s work challenges contemporary assumptions about the appearances of individuals associated with a given place, background, or culture. His video “Hiding Our Faces like a Dancing Wind” (2016) utilizes facial-recognition software on both still and moving images to evoke the histories of photographic evidence that served to identify or classify individuals through their facial characteristics. Matthew Connors has a longtime interest in representing individuals as part of collective cultures, as well as frictions between citizens and their governments. In a series of recent photographs made over several trips to North Korea from 2013 to 2016, he combines a documentary style with a more metaphoric approach, capturing images of people as well as charged symbols. In a special project conceived for the exhibition, Adelita Husni-Bey led a multiday workshop with former and current members of MoMA Teens programs that imagined possible uses for the Museum after a future fictional global disruption. B. Ingrid Olson frames photographs of figures or body parts, including her own,within other pictures or within acrylic boxes. By presenting the body through both literal and metaphorical mirror effects, as in “Felt Angle, box for standing” (2017), or “Model for a folded room, bound girdle” (2017), Olson’s works challenge clear-cut understandings of psychology and identity. Sofia Borges’s photographs depict masks and models, often through manipulations of images she originally shot in museums, zoos, aquariums, or archival collections—all institutions in which display mechanisms play a central role. Her works, such as the immersive wallpaper work “Theatre, or Cave” (2014), invite viewers to experience the artifice and spectacle of photographic representation. Throughout the history of photography, photographs have served as a way to remember those who have passed. Harold Mendez’s photographs from the Necrópolis Cristóbal Colón and other nearby funerary sites in Havana, such as “At the edge of the Necropolis” (2017) or “Siempre serás” (2017) address this role by capturing the faded identifying markers on tombstones or the detritus left behind at graves and memorials by the living. The exhibition also includes an excerpt of Shilpa Gupta’s 2014 project in which she represented 100 individuals, who had changed their surnames for various political, familial, or emotional reasons, with a framed picture that had been sliced into two. The pieces, which are often not figurative depictions, are placed close enough to their mates that viewers can find and “complete” the whole image, but they can also be read as fragmented portraits of an individual’s identity. In their collaborative multi-photograph work “The opposite of looking is not invisibility. The opposite of yellow is not gold” (2016), Hương Ngô and Hồng-Ân Trương mined their own family albums for 1970s-era snapshots featuring their mothers, both of whom immigrated to the US from Vietnam. The artists juxtaposed these photographs with textual excerpts from transcripts of US Congressional hearings about Vietnamese refugees, setting terms such as “aliens” or “illegals” alongside intimate family photographs. Multiple photographs and the premiere of a new two-channel video from Sam Contis’s series “Deep Springs” (2017) illustrate actions and relationships between bodies. The series is set at the historically all-male liberal arts college of the same name, situated in the remote high desert of California. Contis’s subjects are pictured on the brink of adulthood. Here, such development is informed by group social dynamics and by connection to the western landscape.

Info: Curator: Lucy Gallun, The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), 11 West 53 Street, New York, Duration: 18/3-19/8/18, Days & Hours: Sat-Thu 10:30-17:30, Fri 10:00-20:00, www.moma.org