ART-TRIBUTE:Infinite Garden-From Giverny to Amazonia, Part I

It was believed that gardens had been buried by modernity under the triumph of green spaces limiting the organic to functional areas. Yet, they remain a source of fertile inspiration all along the 20th Century and continue to deeply appeal to many artists. The garden captivates, not only for its nourishing, curative and ornamental virtues but also for its subversion (Part II, Part III).

It was believed that gardens had been buried by modernity under the triumph of green spaces limiting the organic to functional areas. Yet, they remain a source of fertile inspiration all along the 20th Century and continue to deeply appeal to many artists. The garden captivates, not only for its nourishing, curative and ornamental virtues but also for its subversion (Part II, Part III).

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Centre Pompidou-Metz Archive

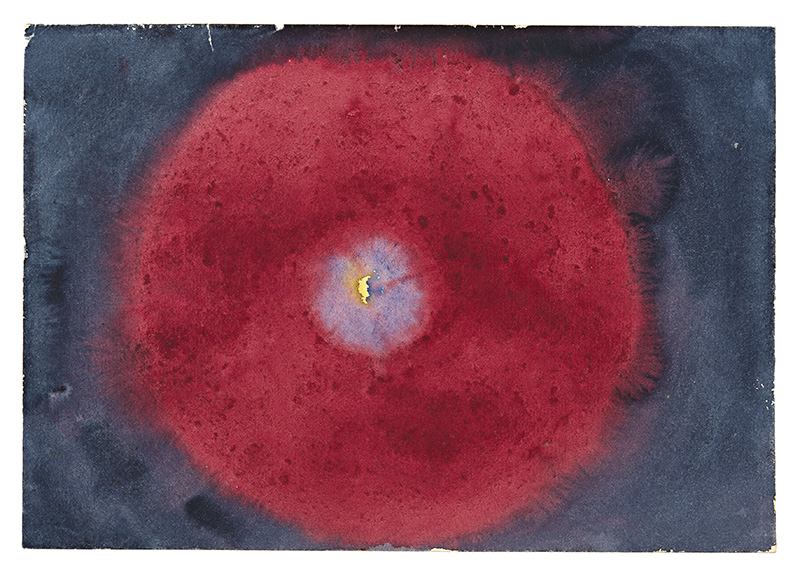

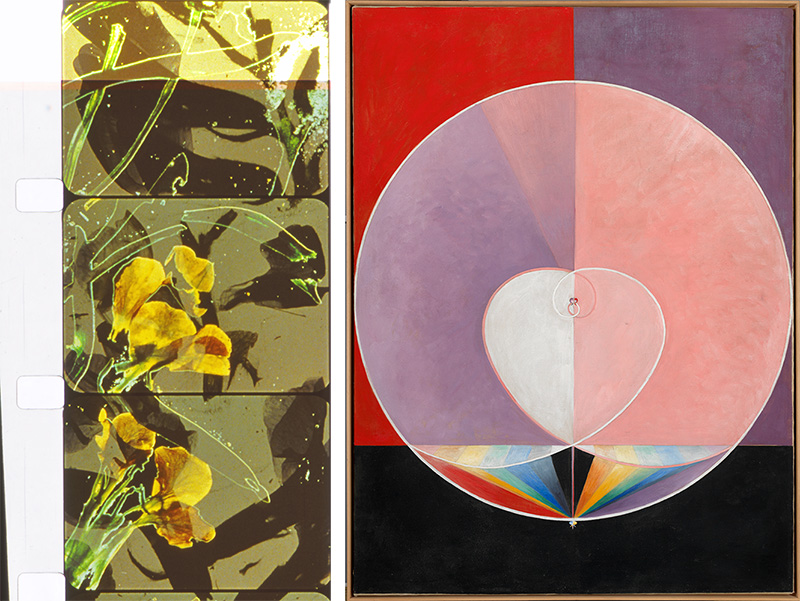

The exhibition “Infinite Garden From Giverny to Amazonia” at the Centre Pompidou-Metz explores the garden as an infinite territory. It offers a home to hybridisation, experimentation and strangeness to the eyes of many an artist. A perpetual source of inspiration, the exhibition reunites around 300 works from the late 19th Century to the present day. An open trail to discover unaccompanied throughout the town of Metz, via the arrangement of three outdoor artists’ gardens, invites visitors to stroll through the exhibition, as if through a terra incognita. The gallery “Cosmic Spring” opens on a primary garden that would cease to be Eden-like to become more telluric and geological. This shapeless garden, between sterility and fertility is made of earth, mud, silt and manure: life and death of all things. These elementary forces fascinate the Surrealists at an early stage. In 1935, André Breton was in awe of the “Jurassic fauna” of the botanical garden of Tenerife, whose thousand-year old veteran dragon tree seemed to have its roots plunge into the Prehistory. The animated film “Panspermia” (1990) by Karl Sims illustrates this extravagant scenario: a stone fruit coming from space land on a desert planet where it releases thousands of small seeds. Theses multicoloured jewels will then give birth to quantity of plants such as reeled ferns like fractals or branches in the shape of DNA. In Yayoi Kusama’s works, the diversity of plants, their extravagant shapes, sparkling colours and heady fragrances, provokes hallucinogenic effects. Gardens are also cemeteries, where the memories of the bodies are kept and where certain struggles of history are crystallised. Like Tetsumi Kudo who incorporates human limbs in his toxic flower beds installation “Grafted Garden / Pollution – Cultivation – New Ecology” (1970-71). From Giverny to Amazonia: the second part of the path recalls the irreversible and extensible scale of a garden, microcosm and macrocosm at the same time. To translate this duality, the scenery of the second gallery is completely open and proposes a stroll in immersive installations where the principle of closure is deeply questioned. Yto Barrada explores what she contemplates as the “Βotany of power”. Thu Van Tran investigates the history of Brazilian rubber trees transplanted by the French in Vietnam to produce rubber at the beginning of the ‘30s. Ernesto Neto after living with the Amazonian tribes of the Huni Kuin who initiate him into the healing rituals of the forest, following this experience, he creates immersive and olfactory installations such as “Flower Crystal Power” (2014), half-way between sculpture and architecture.. Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster’s tropical diorama especially revived for the Centre Pompidou-Metz, calls up the literary and fantasised dimension of the virgin forest. In A Garden For Scenery, among other artists Daniel Steegmann Mangrané reconfigures the perception of the exhibition space by playing with lighting and materials. This option offers the possibility of a visit under a variable sun, and on a slightly undulating ground: the visitor ventures on “forking paths” to borrow Jorge Luis Borges’ expression. Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster creates a tropical diorama, a proliferating garden-library in line with a series of installations inspired from illusionist’s devices of the 19th century. Ernesto Neto takes the Forum of the Centre Pompidou-Metz with a monumental sculpture, “Leviathan-Main-Toth” (2005), whose membranes take the shape of a biological landscape on a building scale. As part of the exhibition, the Centre Pompidou-Metz goes beyond its walls and partners up with the city of Metz to organise “Art in gardens”, an ephemeral implantation of three gardens made by artists who explore the theme of the movement of plants. Peter Hutchinson is a major artist of the Land Art movement which is also presented in the exhibition. For the “Jardin des Régates”, he revives his work “Thrown Ropes”. In front of the Centre Pompidou-Metz Lois Weinberger, interested by the phenomena of spontaneous vegetation, uses anarchic means to create a garden made up of hundreds of plastics pots filled with earth, left in the open air and offered to the spontaneous sowing of wind, insects and birds. François Martig creates a garden named “Gleis 1. Summoning the history of the Lorraine region”, this garden is made up of “obsidional” plants (from the Latin obsis “under state of siege”), which were brought voluntarily or not by enemies or allies during the war and have spread across Lorraine.

Info: Curators: Emma Lavigne and Hélène Meisel, Research: Tristan Bera, Centre Pompidou-Metz, 1 Parvis des Droits de l’Homme, Metz, Duration: 18/3-28/8/17, Days & Hours: Mon & Wed-Thu 10:00-18:00, Fri-Sun 10:00-19:00, www.centrepompidou-metz.fr