ART-TRIBUTE:Women Artists and Postwar Abstraction, Part I

In the decades after World War II, societal shifts made it possible for larger numbers of women to pursue careers as artists. Abstraction dominated artistic practice internationally between 1945 and the late ‘60s, as many artists sought a formal language that might transcend national and regional narratives, and for women artists, additionally, those relating to gender. But despite new opportunities, women often found their work dismissed in the male-dominated art world and, without the benefit of Feminist advances that would take root in the ‘70s, they had few support network (Part II)

In the decades after World War II, societal shifts made it possible for larger numbers of women to pursue careers as artists. Abstraction dominated artistic practice internationally between 1945 and the late ‘60s, as many artists sought a formal language that might transcend national and regional narratives, and for women artists, additionally, those relating to gender. But despite new opportunities, women often found their work dismissed in the male-dominated art world and, without the benefit of Feminist advances that would take root in the ‘70s, they had few support network (Part II)

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: MoMA Archive

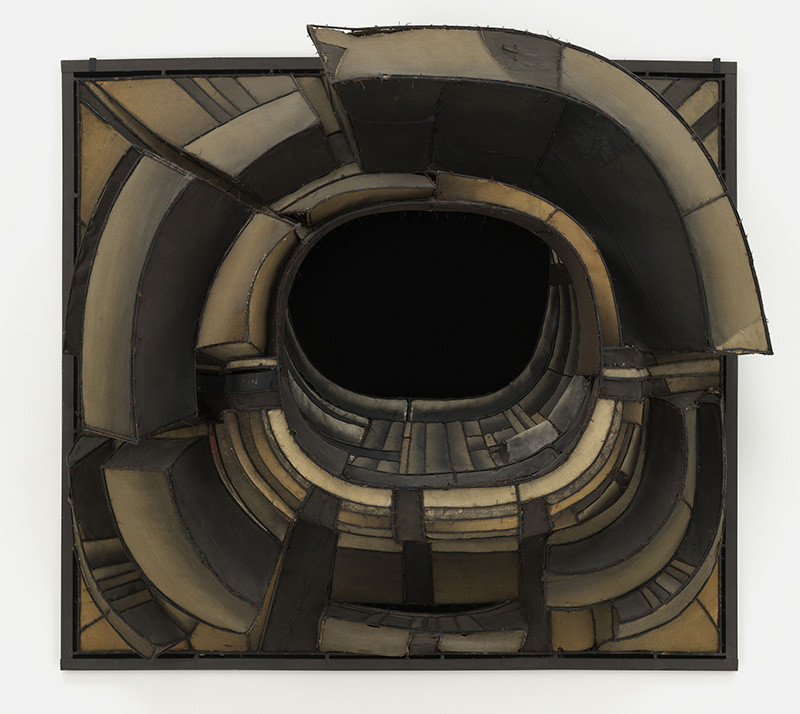

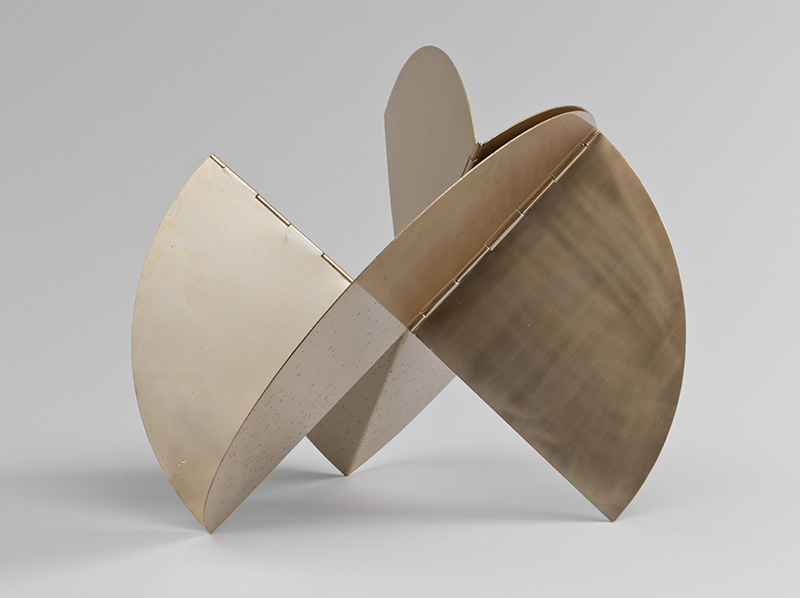

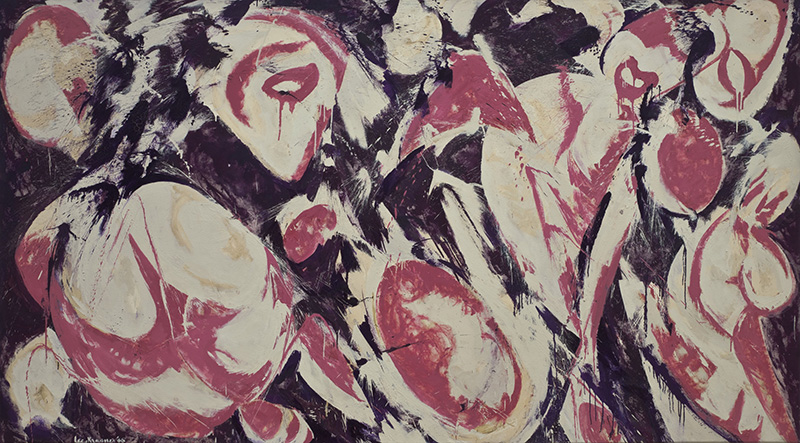

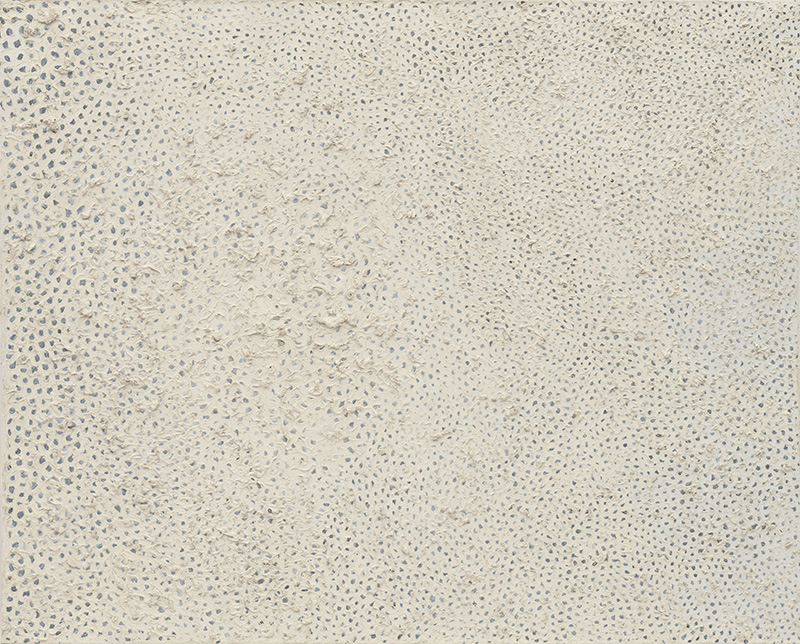

The Exhibition “Making Space: Women Artists and Postwar Abstraction” at MoMA presents 100 works in a diverse range of mediums by more than 50 international woman artists. Drawn entirely from the Museum’s collection, the exhibition includes works that were acquired soon after they were made in the ‘50s and ‘60s, as well as many recent acquisitions. Following a trajectory that is at once loosely chronological and synchronistic, it is organized into five sections: Gestural Abstraction, Geometric Abstraction, Reductive Abstraction, Fiber and Line, and Eccentric Abstraction. Building on the legacies of modernism in the early 20th Century, artists found new urgency for their abstract impulses, whether in the form of existential gestures, the rationalizing order of geometry, or the potential of new materials and processes. Gestural Abstraction: In the postwar climate, women artists’ successes were hard won in the hyper-masculine world of Abstract Expressionism. The Abstract Expressionists’ fervent mark-making came to signify the artists’ existential struggles and, particularly in the case of large-scale paintings, heroic actions. Geometric Abstraction: Constructivist tendencies became increasingly transnational in the postwar period, as the geometric legacy of European Cubism and Constructivism travelled across geographic lines. This approach, based on reason and precision, flourished concurrently and in sharp contrast to the subjective, gestural style of Abstract Expressionism. Reductive Abstraction: A number of artists, working in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, reacted against the emotionally charged gestures of Abstract Expressionism. Their minimalist works feature flat, uninflected surfaces and highly simplified, mathematically regular forms, often based on a grid. Along with dozens of men whose work was heralded under the umbrella of Minimalism, there were a few key women, who pursued their uncompromising visions at a certain distance from the mainstream of the movement. Fiber and Line: Reclaiming the historical coding of textiles as “women’s work”, the artists featured in this section created radical woven forms that upend traditional boundaries between art and craft. Like their minimalist contemporaries, artists working with fiber exploited the gridded structure of warp and weft, a logic that is also reflected in a large group of drawings and prints featuring gridded, woven, or lace-like lines. Eccentric Abstraction: In the ‘60s, women artists were among the key pioneers of a new direction for abstraction that emphasized unusual materials and processes. Employing found, sometimes abject objects and raw or viscous matter, these artists injected subversive and obliquely feminist content into the rhetoric of aesthetic purity that had been one of the defining threads of postwar modernism and abstraction.

Info: Curators: Starr Figura, Sarah Meisterand Hillary Reder, The Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street, New York, Duration: 15/4-16/8/17, Days & Hours: Mon-Thu & Sat-Sun 10:30-17:30, Fri 10:30-20:00, www.moma.org