ART-TRIBUTE:Francis Picabia’s Retrospective at MoMA, Part II

Francis Picabia lived through the devastation of two World Wars, which fueled his persistent nihilism and profound sense of the absurd. Today he is best known as an irreverent Dadaist, but like no other artist before him, created a body of work that defies consistency and categorization, ranging from Impressionist landscapes to Abstraction, from paintings of machines to photo-based nudes, and from performance and film to poetry and publishing (Part I)

Francis Picabia lived through the devastation of two World Wars, which fueled his persistent nihilism and profound sense of the absurd. Today he is best known as an irreverent Dadaist, but like no other artist before him, created a body of work that defies consistency and categorization, ranging from Impressionist landscapes to Abstraction, from paintings of machines to photo-based nudes, and from performance and film to poetry and publishing (Part I)

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: MoMA Archive

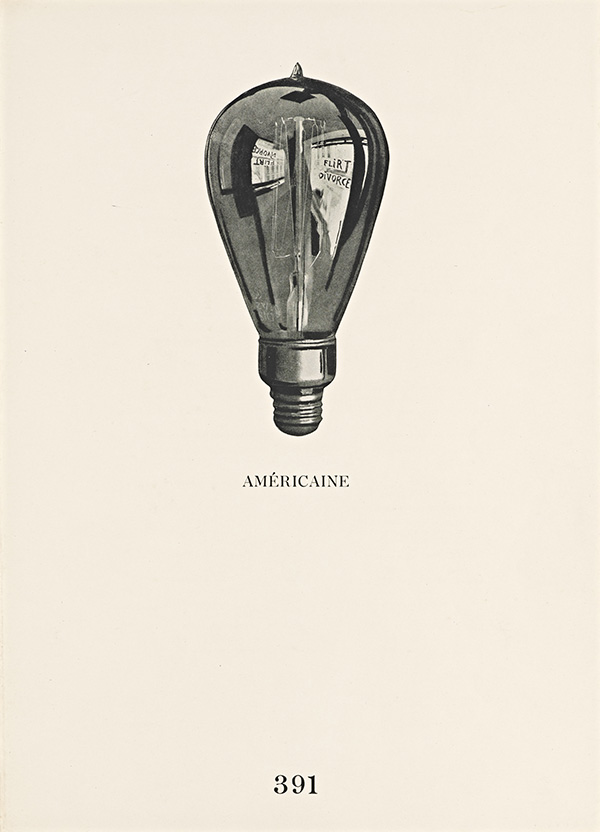

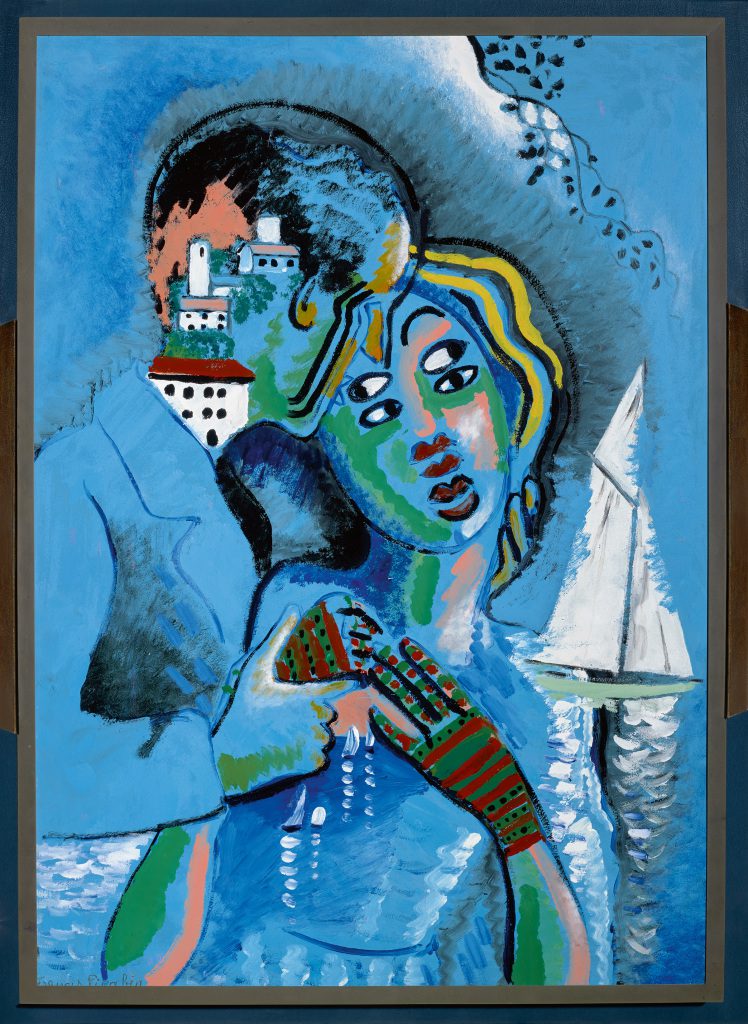

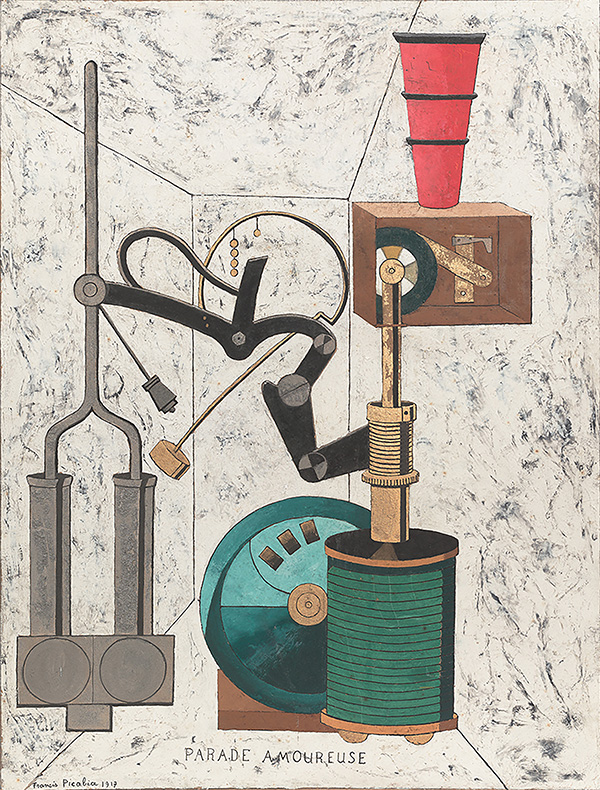

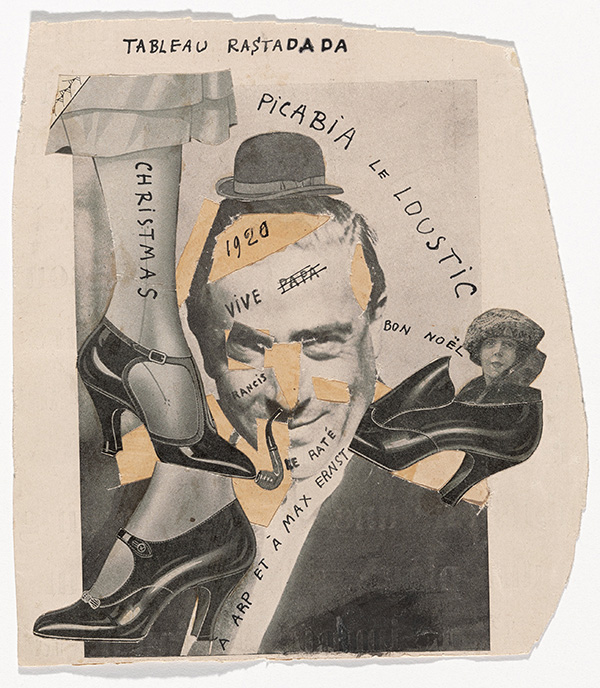

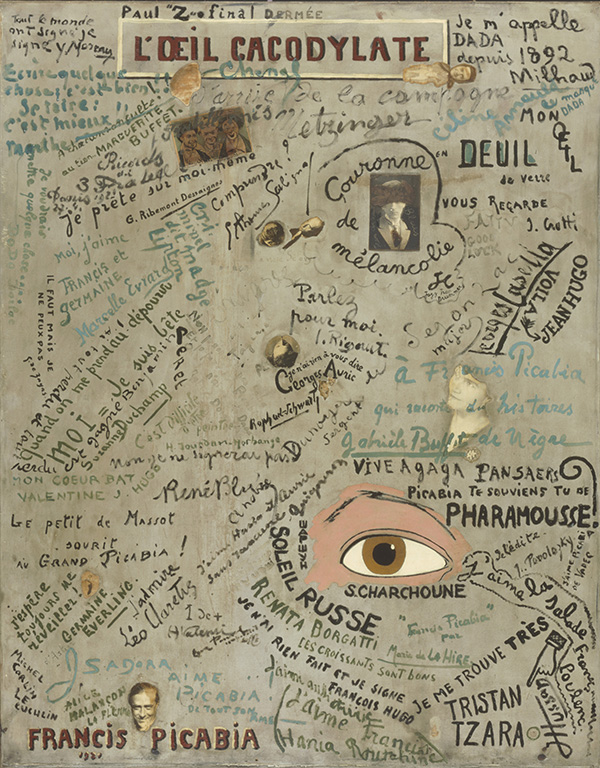

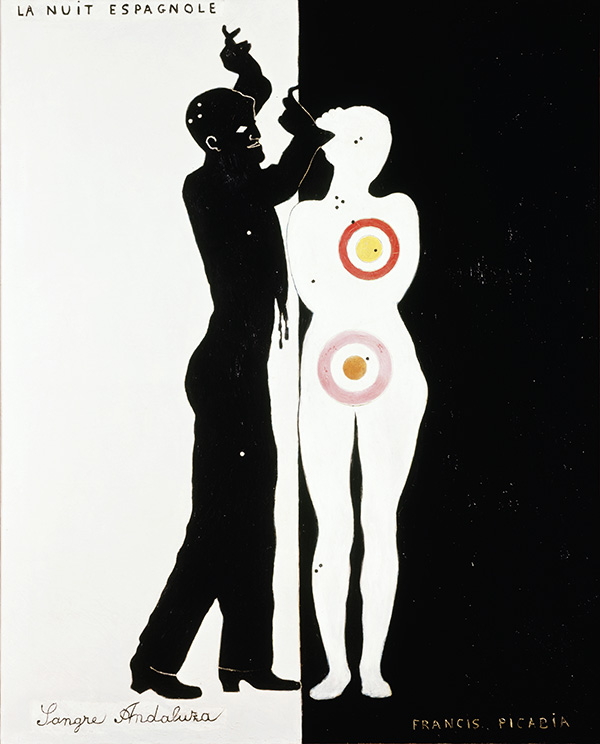

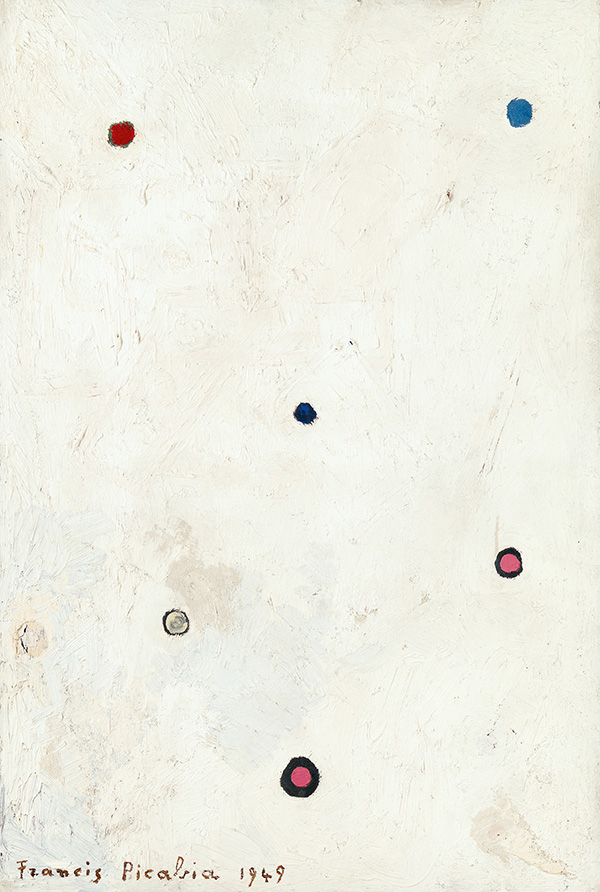

The retrospective “Francis Picabia: Our Heads Are Round so Our Thoughts Can Change Direction” at MoMA, divided in 10 thematic sections, covers the full range of Picabia’s career. The core of the exhibition comprises 125 paintings, along with 45 key works on paper, one film, a selection of printed matter, and sound recordings of selected poems and writings in order to advance understanding of Picabia’s unruly genius and its vital place within the history of Modern Art. The title is an aphorism coined by Picabia in 1922, and it aptly encapsulates the nonlinear, circular character of his artistic practice. Beginnings, 1905–1911: Picabia first made his name as an after-the-fact Impressionist painter, and the exhibition begins with works like: “Effect of Sunlight on the Banks of the Loing, Moret” (1905) and “Untitled (Notre-Dame, Paris)” (1906), which call to mind artists such as Claude Monet and Alfred Sisley. Picabia is believed to have worked from photographic postcards rather than immersing himself in nature and painting outdoors. In this, he travestied the original spirit of Impressionism. Abstractions, 1912–1914: In the summer of 1912, Picabia turned to abstraction, the inclusion of his works at the Salon d’Automne and Armory Show. When he returned to Paris in the summer of 1913, Picabia began work on a pair of monumental canvases: “Udnie (Young American Girl: Dance)” and “Edtaonisl (Ecclesiastic)” (both 1913), which are displayed together for the first time in the exhibition, the art critics almost universally mocked these works when they were unveiled at the 1913 Salon d’Automne in Paris, but after World War II, they were subsequently heralded as early precedents for Postwar Abstract Painting. Mechanomorphs and Dada, 1915–1922: During World War I, Picabia’s avoided military service by seeking exile in New York, Barcelona, and Switzerland. He painted, drew, and became active as a writer, but the mainstay of his activity was contributing to and editing journals. The machine appears in paintings such as “Very Rare Picture on the Earth” (1915). After the war, Picabia returned to Paris, where he joined Tristan Tzara and other Dadaists in an all-out assault on the culture of rationality that they held responsible for the war. Works on view from this period include The “Cacodylic Eye” (1921), an iconoclastic group portrait of the Paris Dada movement bearing the signatures of over 50 friends and acquaintances, and “St. Vitus’s Dance (Rat Tobacco)” (1919–20, modified 1946–49), an empty frame strung with yarn between which words were suspended. Dalmau, Littérature, and Salon Ripolins, 1922–1924: This section of the exhibition that pays homage to the “Exposition Francis Picabia”, that opened in Barcelona on 18/11/22 featuring 50 new works on paper and is based archival photographs. Picabia continued to submit paintings to the Paris salons. Instead of traditional oils, he used commercial enamel paints, creating works in both abstract and figurative modes. The bold graphic character and sinister eroticism of “The Spanish Night” (1922) and “Animal Trainer” (1923) are also seen in the contemporaneous, black-and-white covers Picabia designed for the journal Littérature. Ciné-Theater-Dance, 1924: The composer Erik Satie approached Picabia about collaborating on a ballet in 1924, and Picabia had the idea of also producing a film, which he imagined as “a parody of cinematic action”. Cinema and dance interacted spectacularly when the humorously titled “ballet Relâche” and the film “Entr’acte” premiered on 4/12/24. The film is screened in the exhibition alongside photographs of Picabia’s sets, costumes and various related drawings, including portraits of people involved in the ballet’s production. Collages and Monsters, 1924–1927: In January 1925, Picabia left Paris for the south of France. The move precipitated an intensely productive period of painting, as seen in his so-called “Monsters”, pictures of embracing couples and carnival characters, rendered in the acidic colors and saturated sheen of commercial enamel paint. Picabia also revisited older paintings with increasing frequency. Commercial enamels proved well suited to amending, adjusting, and covering over prior works, as seen in “The Lovers (After the Rain)” (1925), which Picabia painted over an earlier abstraction. Transparencies, 1927–1930: In 1927, Picabia began creating the works known as “Transparencies” by alternating layers of paint with layers of resinous varnish, As seen in the exhibition, they range from the complex imagery of paintings like “Sphinx” (1929) to the masterful refinement of “Aello” (1930), “Mélibée” (1930), and “Salomé” (1930). Eclecticism and Iconoclasm, 1934–1938: This was a period of intense material experimentation and reworking for Picabia, as he shuttled back and forth between Paris and the French Riviera. Works like “Fratellini Clown” (1937–38) and “The Spanish Revolution” (1937), exemplify the sense of creeping doom that was spreading throughout Europe, as the threat of fascism and totalitarian ideologies took center stage. Picabia continued to organize galas at the municipal casino of Cannes, he also created facial superimpositions and photo-based portraits. Photo-Based Paintings, 1940–1943: Picabia remained in the south of France throughout World War II, where he painted works that combine kitsch subjects, popular culture, and politics in an unsettling mix. Many of Picabia’s wartime paintings recombine images lifted from photographs published in late-30s soft-core pornography magazines. Postwar Abstractions and Points, 1946–1952: In an interview in November 1945 Picabia announced his return to abstraction with the words “Figurative art is dead”. The exhibition concludes with Picabia’s post‐WWII abstractions, including a group of encrusted, thickly repainted monochromatic “point” or “dot” paintings. Picabia’s final paintings: “The Earth Is Round” (1951) and “La Terre est ronde / K.O.” (c. 1951) are on view, along with a number of illustrated books he produced in his last years.

Info: Curators: Anne Umland and Cathérine Hug, Curatorial Assistant: Züri Talia Kwartler, Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), 11 West 53 Street, New York, Duration: 21/11/16-19/3/17, Days & Hours: Mon-Thu & Sat-Sun 10:30-17:30, Fri 10:30-22:00, www.moma.org

![Francis Picabia, Optophone [I], 1922, Kravis Collection, © 2016 Artist Rights Society (ARS)-New York/ADAGP-Paris, Photo: The Museum of Modern Art, John Wronn, MoMA Archive](http://www.dreamideamachine.com/web/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/0415.jpg)