ART CITIES:Frankfurt-Yokohama 1868–1912

The exhibition “Yokohama 1868–1912: When Pictures Learned to Shine” at Museum Angewandte Kunst explores the history of photography in Japan, that really began in 1848, with the introduction of the daguerreotype by European traders. The camera obscura, had been imported at a much earlier date. Its application, by the limited number of scholars studying Western science at that time, was limited to the hand-tracing of reflected images.

The exhibition “Yokohama 1868–1912: When Pictures Learned to Shine” at Museum Angewandte Kunst explores the history of photography in Japan, that really began in 1848, with the introduction of the daguerreotype by European traders. The camera obscura, had been imported at a much earlier date. Its application, by the limited number of scholars studying Western science at that time, was limited to the hand-tracing of reflected images.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Museum Angewandte Kunst Archive

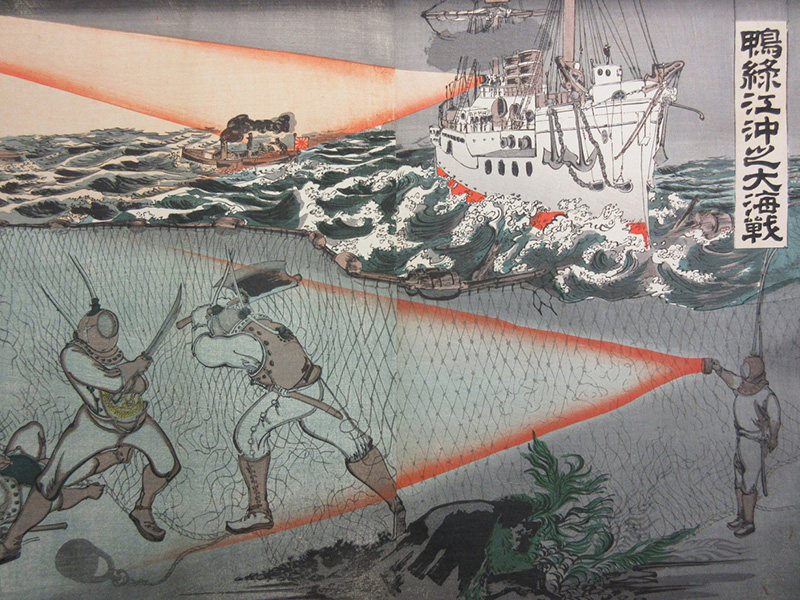

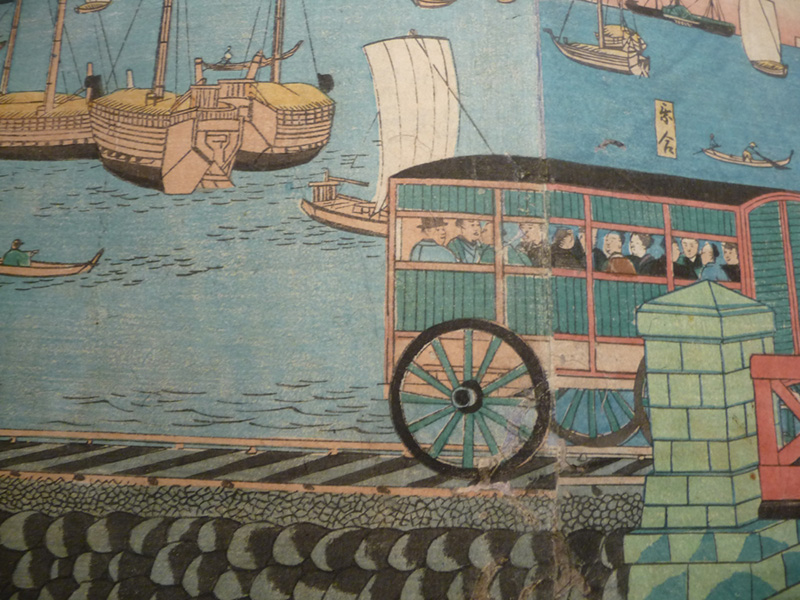

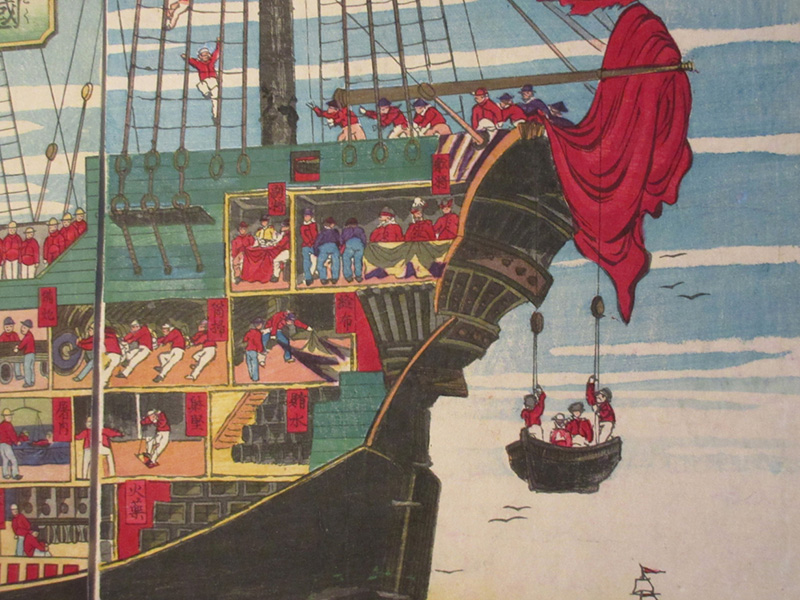

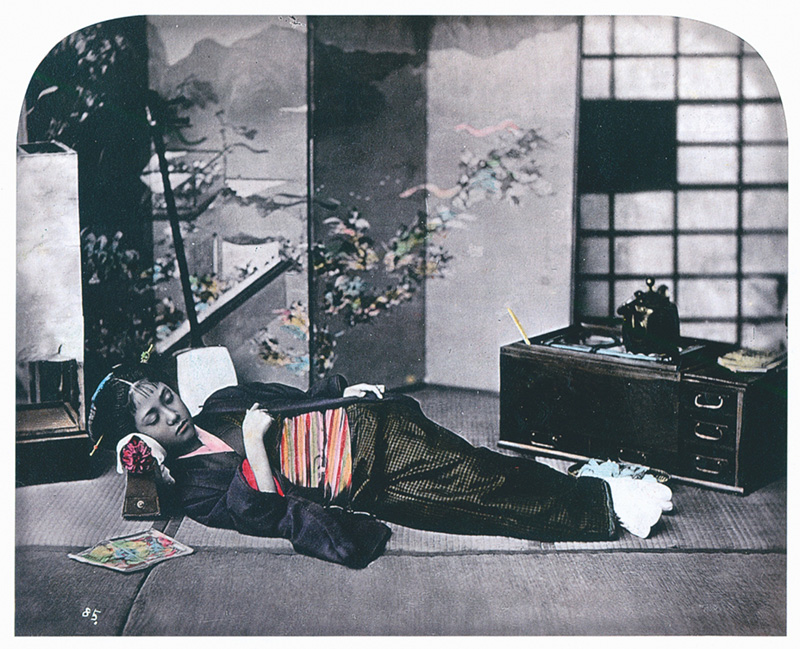

Yokohama is, symbolically speaking, where Japanese modernism began and the country first opened up to the world. The first photo studios were founded in Yokohama around 1860 during the period of economic collapse at the end of the Edo period. No other Western scientific achievement was taken on in Japan so quickly and successfully as photography. In 1840-41, the clockmaker Ueno Shunnojö Tsunetari, who was employed at the time in the service of the Shogun regime, subjected the Daguerreotypes to chemical-physical studies, He also ordered equipment to make his own Daguerrotypes, which, however, could not be imported aboard a Durch ship to Nagasaki until as late 1848. At first it was especially the feudal lords of the time, who, as a result of their interest in began experimenting with the Daguerreotype in Japan. They exchanged information about the new process in letters to each other and described the Daguerreotypes as “Stamped mirrors”. The technical process of photography had thus already been introduced even before the opening of the country enforced by the Americans in 1853. After more than 250 years of national isolation, Japan was forced by the West to open itself up again. Only the Dutch were permitted during this period of isolation to conduct trade and they thus provided the only window to the West. The modernisation of the Japanese State was accelerated during the Meiji period as a means of self-protection. At the same time in Europe, however, there was also a great interest the ukiyo-e, the Japanese coloured woodblock print, which, triggered off a bourgeois Japanese fashion in all the centres of Europe, the new medium of photography was an obvious means, with which to react to this demand commercially. The Japanese term for photography, “Shashin” established itself in the mid-I870S, nearly three decades after photography had been imported to Japan from the West. In the beginning, the photographic process was considered hazardous to one’s health and even deadly. As a result, at first it was especially Samurai who posed in front of the camera and only after circa 1860 also citizens, who wanted to have their own portraits saved for posterity with the help of this modern technology. After these inirial fears were put aside, the road to a commercial application of photography was opened. The pioneers of Japanese photography initially availed themselves of the cliché of a naively exotic image of Japan. As time went on, however, they subtly departed from that aesthetic with masterfully composed motifs and a style of their own. As the new image technologies gained currency, the interest in the traditional craft of the ukiyoe woodblock print began to fade, around 1900 the old art form sprouted one last bizarre blossom in the form of war propaganda before disappearing almost entirely. With a dramatic decline in production, many Japanese artists who worked in woodblock print shops became unemployed. But the growing market for photography offered them a new opportunity to apply their talents. The technical skill of some artists reflected a method of application that raised the practice of hand coloring photographs to a respected art of striking beauty.

Info: Curator: Dr Stephan von der Schulenburg, Museum Angewandte Kunst, Schaumainkai 17, Frankfurt, Duration: 8/10/1-29/1/17, Days & Hours: Tue & Thu-Sun 10:00-81:00, Wed 10:00-20:00, www.museumangewandtekunst.de