TRACES: Ilya Kabakov

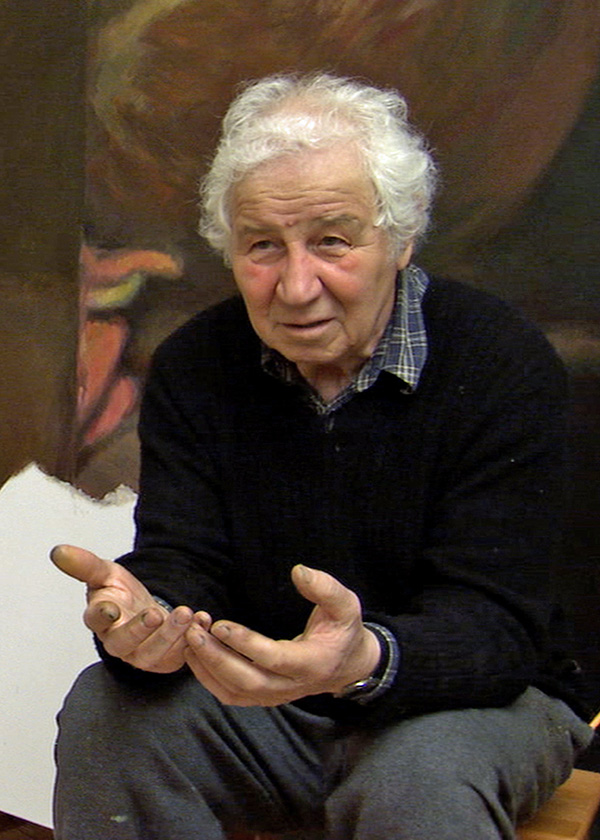

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Ilya Kabakov (30/9/1933-27/5/2023), an artist of note in two distinctly polar disciplines. While living in the Soviet Union for 30 years, he was a well-known, albeit officially sanctioned, children’s book illustrator and simultaneously amassing a substantial body of unofficial Avant-Garde work. Since leaving the Soviet Union in 1988, he has been prolific, he is now considered the foremost post-Stalinist Russian artist. His prime means of artistic expression has been sprawling installations largely based on Soviet-related themes. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Ilya Kabakov (30/9/1933-27/5/2023), an artist of note in two distinctly polar disciplines. While living in the Soviet Union for 30 years, he was a well-known, albeit officially sanctioned, children’s book illustrator and simultaneously amassing a substantial body of unofficial Avant-Garde work. Since leaving the Soviet Union in 1988, he has been prolific, he is now considered the foremost post-Stalinist Russian artist. His prime means of artistic expression has been sprawling installations largely based on Soviet-related themes. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Dimitris Lempesis

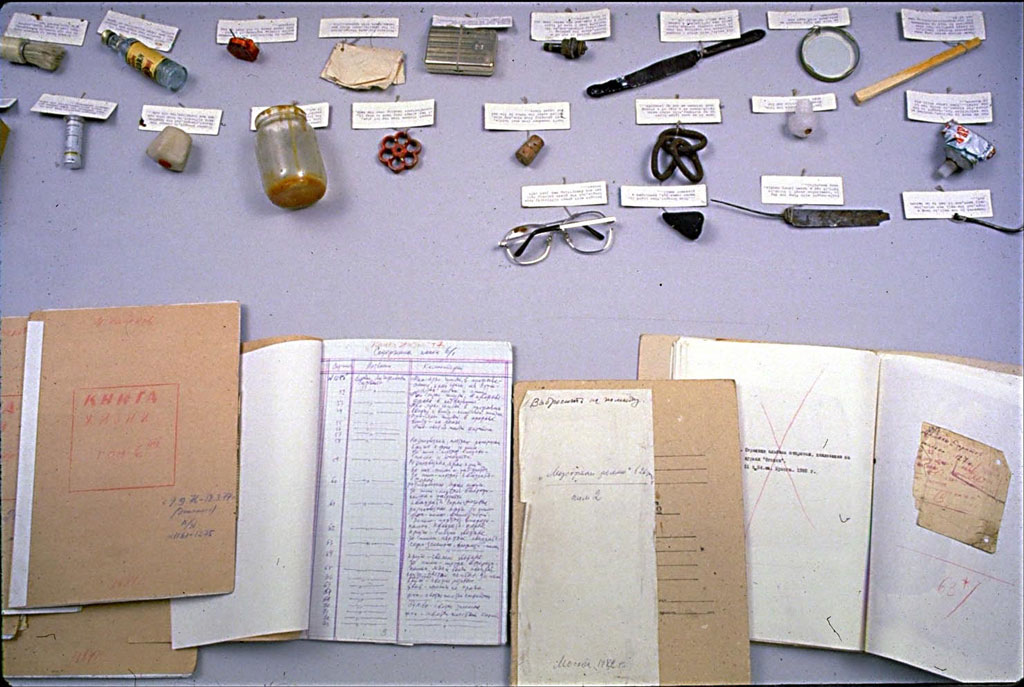

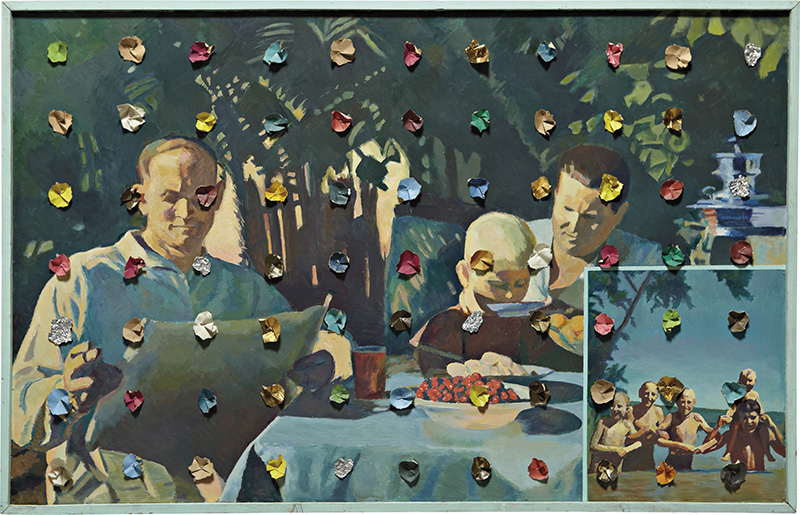

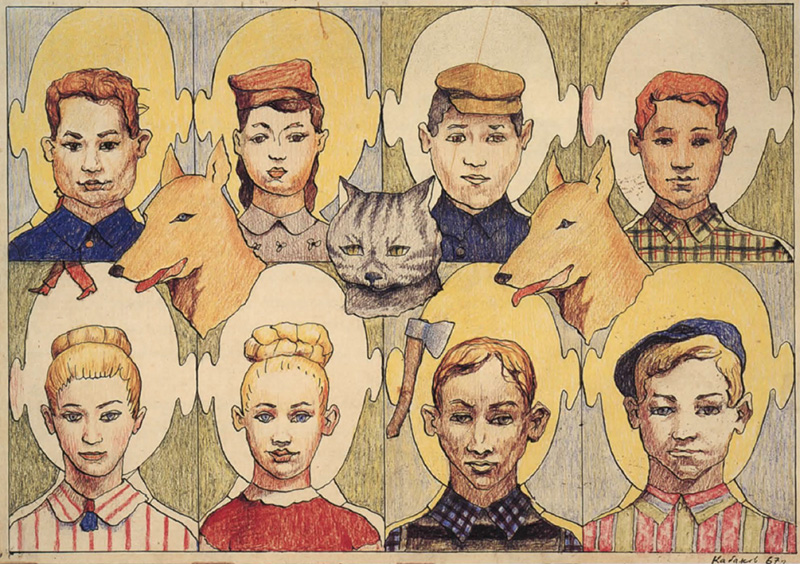

Ilya Kabakov was in Dniepropetrovsk, Ukraine, to Jewish parents. By chance, Kabakov attended a professional elementary art school between the ages of 7 and 16. He attended Moscow Secondary Art School between 1945 and 1951. He graduated from Surikov Institute of Arts in 1957. He maintained that creating art continued to be a struggle. In 1959, Kabakov became a “candidate member” of the Union of Soviet Artist (he later became a full member in 1965). This status secured him a studio, steady work as an illustrator and a relatively healthy income by Soviet standards. Between 1953-55 Kabakov began making his first unofficial works, which he called “drawings for myself”. The phrase serves as a title for the works and an explanation. None of these early projects amounted to more than sketches on paper. They were never titled, and they were often similar in style to his book illustrations. Throughout his career the tension between official labor and unofficial art would haunt Kabakov. In 1962 Kabakov produced several series of Absurd drawings. These were eventually published in a 1969 Prague magazine. Prior to this, however, Kabakov had his first taste of publicly challenging the Soviet regime. In 1965 a member of the Italian Communist Party exhibited a number of works by Soviet artists in L’Aquila, Italy. Kabakov lent a series of drawings titled “Shower”. Throughout the ‘60s, Kabakov’s work became more experimental and irregular. Some of his best-known motifs begin to develop in this decade. For example, “Queen Fly” (1965) is a smaller and quite unique work in that a decorative, semi-geometric design covers a plywood base and frame. In the ‘70s, several factors led Kabakov to become more conceptually oriented. Unlike many Soviet artists who emigrated to the West in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, Kabakov remained in Russia until 1987. Between 1988 and 1992, Kabakov claimed no permanent home yet stayed in the West, working and living only briefly in various countries. In comparison to many Soviet émigré artists, Kabakov was immediately successful and has remained so ever since. In 1988 Kabakov began working with his future wife Emilia. From this point onwards, all their work was collaborative, in different proportions according to the specific project involved. It was Kabakov’s “Ten Characters” installation mounted in New York that started a series of museum installations. It was also his first solo exhibition. Later in his career, Kabakov began shying away from relying on the Soviet Union as a subject for his installations. One of the first of these is “Auf dem Dach/On the Roof” in which ten rooms, representing a narrative timeline of snapshots from family life, were shown from the vantage point of a rooftop. His “The Palace of Projects” and “Life and Creativity of Charles Rosenthal” marked a further turn toward other forms. Today Kabakov is recognized as the most important Russian artist to have emerged in the late 20th century. His installations speak as much about conditions in post-Stalinist Russia as they do about the human condition universally.

Ilya Kabakov was in Dniepropetrovsk, Ukraine, to Jewish parents. By chance, Kabakov attended a professional elementary art school between the ages of 7 and 16. He attended Moscow Secondary Art School between 1945 and 1951. He graduated from Surikov Institute of Arts in 1957. He maintained that creating art continued to be a struggle. In 1959, Kabakov became a “candidate member” of the Union of Soviet Artist (he later became a full member in 1965). This status secured him a studio, steady work as an illustrator and a relatively healthy income by Soviet standards. Between 1953-55 Kabakov began making his first unofficial works, which he called “drawings for myself”. The phrase serves as a title for the works and an explanation. None of these early projects amounted to more than sketches on paper. They were never titled, and they were often similar in style to his book illustrations. Throughout his career the tension between official labor and unofficial art would haunt Kabakov. In 1962 Kabakov produced several series of Absurd drawings. These were eventually published in a 1969 Prague magazine. Prior to this, however, Kabakov had his first taste of publicly challenging the Soviet regime. In 1965 a member of the Italian Communist Party exhibited a number of works by Soviet artists in L’Aquila, Italy. Kabakov lent a series of drawings titled “Shower”. Throughout the ‘60s, Kabakov’s work became more experimental and irregular. Some of his best-known motifs begin to develop in this decade. For example, “Queen Fly” (1965) is a smaller and quite unique work in that a decorative, semi-geometric design covers a plywood base and frame. In the ‘70s, several factors led Kabakov to become more conceptually oriented. Unlike many Soviet artists who emigrated to the West in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, Kabakov remained in Russia until 1987. Between 1988 and 1992, Kabakov claimed no permanent home yet stayed in the West, working and living only briefly in various countries. In comparison to many Soviet émigré artists, Kabakov was immediately successful and has remained so ever since. In 1988 Kabakov began working with his future wife Emilia. From this point onwards, all their work was collaborative, in different proportions according to the specific project involved. It was Kabakov’s “Ten Characters” installation mounted in New York that started a series of museum installations. It was also his first solo exhibition. Later in his career, Kabakov began shying away from relying on the Soviet Union as a subject for his installations. One of the first of these is “Auf dem Dach/On the Roof” in which ten rooms, representing a narrative timeline of snapshots from family life, were shown from the vantage point of a rooftop. His “The Palace of Projects” and “Life and Creativity of Charles Rosenthal” marked a further turn toward other forms. Today Kabakov is recognized as the most important Russian artist to have emerged in the late 20th century. His installations speak as much about conditions in post-Stalinist Russia as they do about the human condition universally.