TRACES: Kenneth Noland

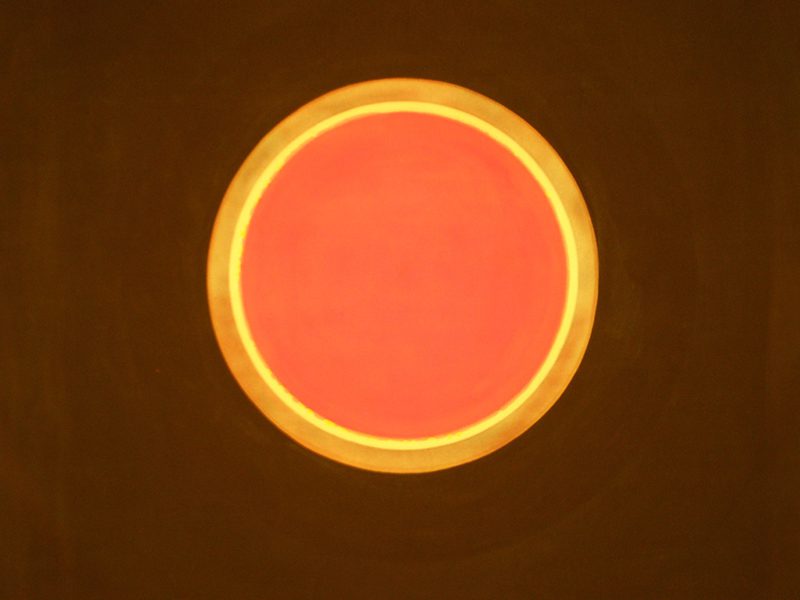

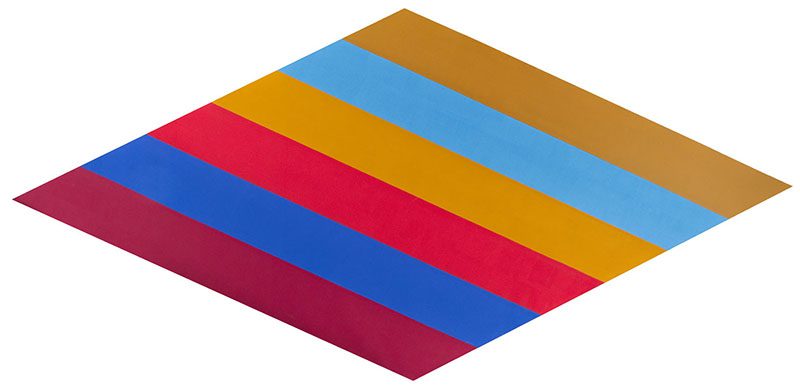

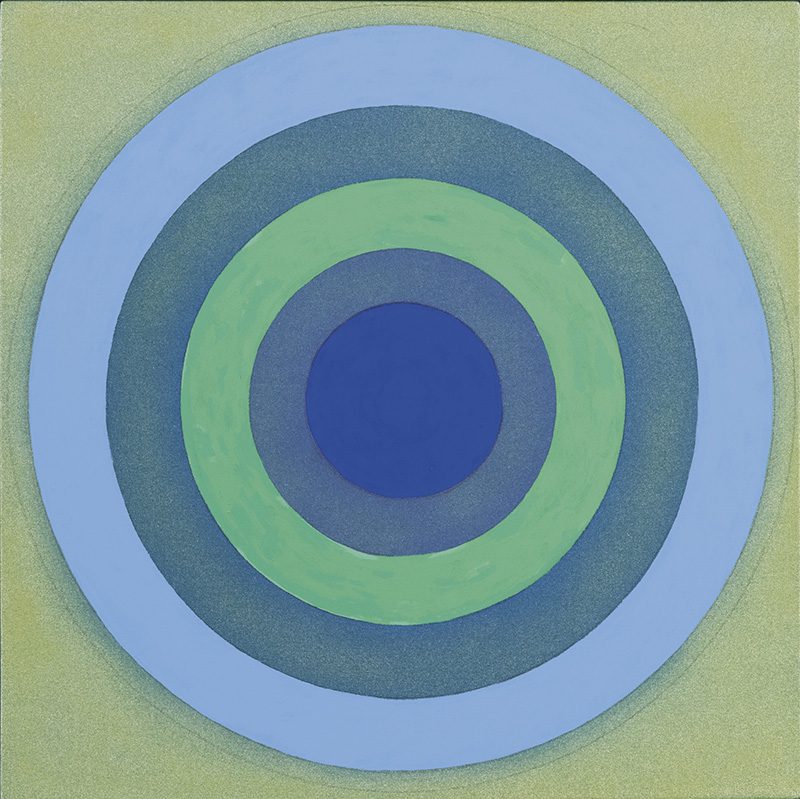

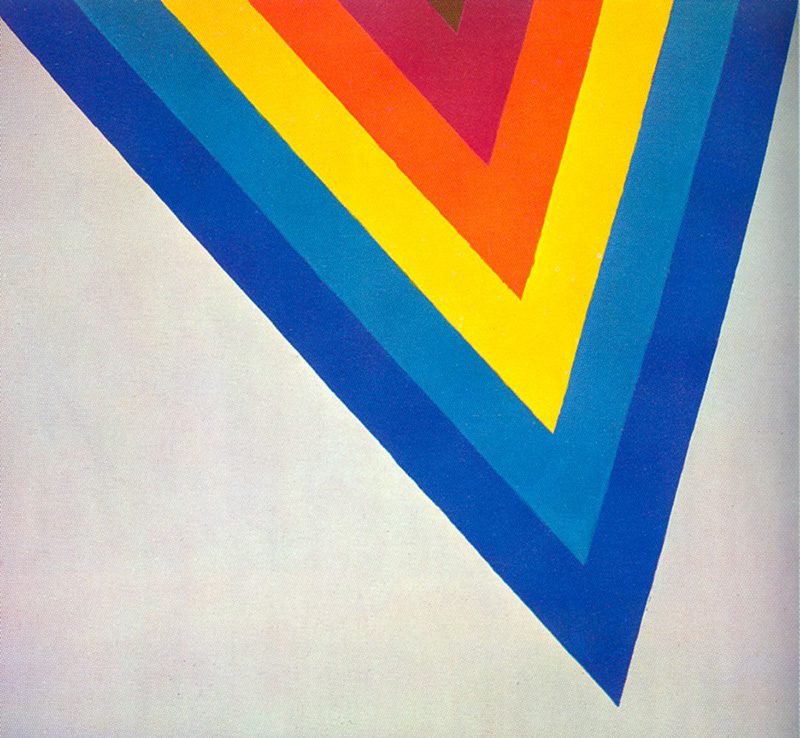

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Kenneth Noland (10/4/1924-5/1/2010), whose brilliantly colored concentric circles, chevrons and stripes were among the most recognized and admired signatures of the postwar style of abstraction known as Color Field painting. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Kenneth Noland (10/4/1924-5/1/2010), whose brilliantly colored concentric circles, chevrons and stripes were among the most recognized and admired signatures of the postwar style of abstraction known as Color Field painting. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Dimitris Lempesis

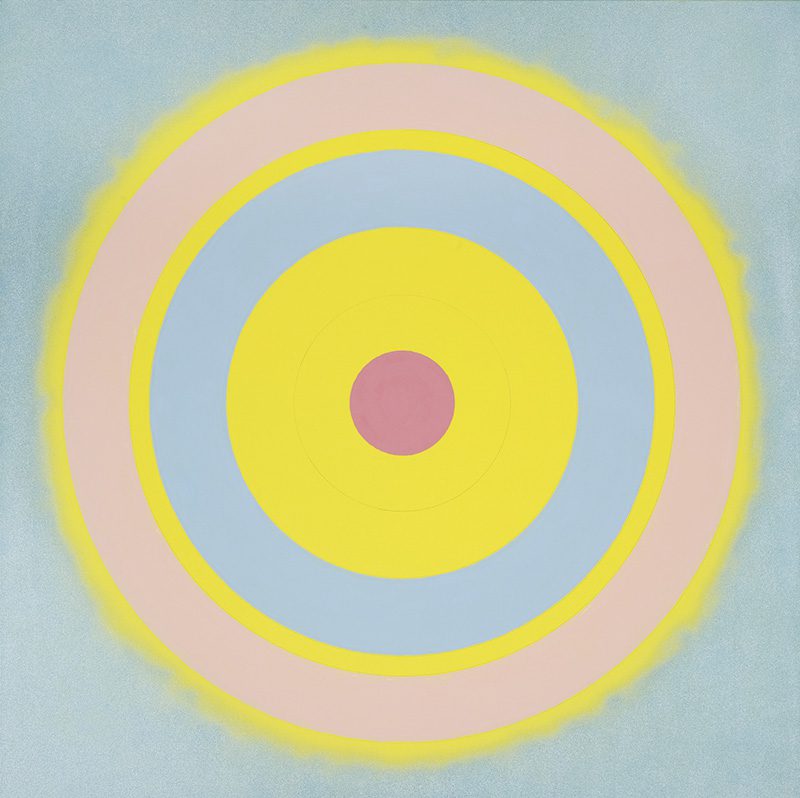

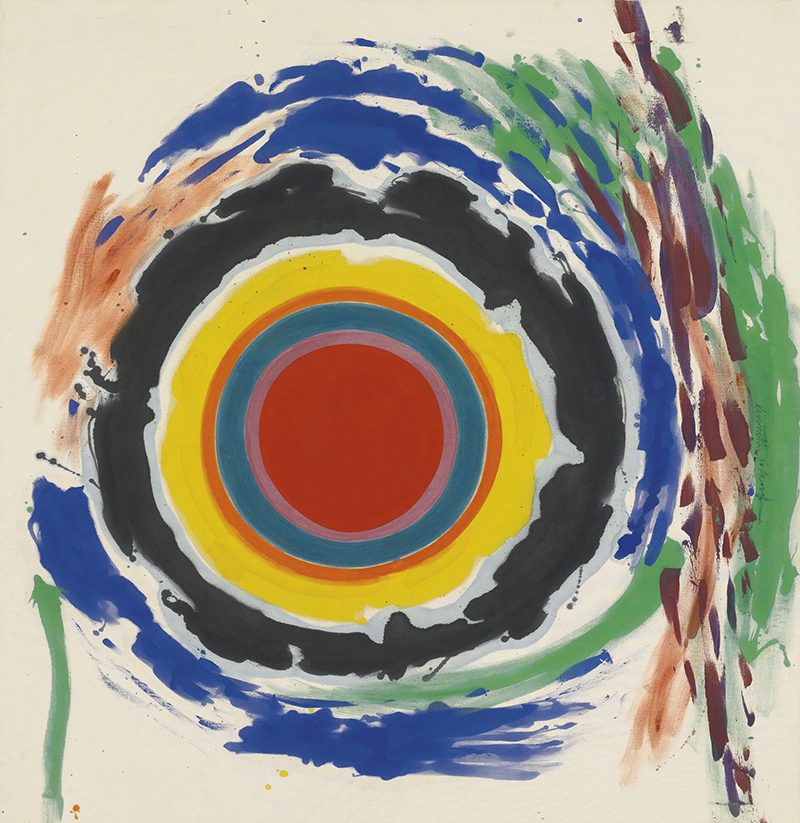

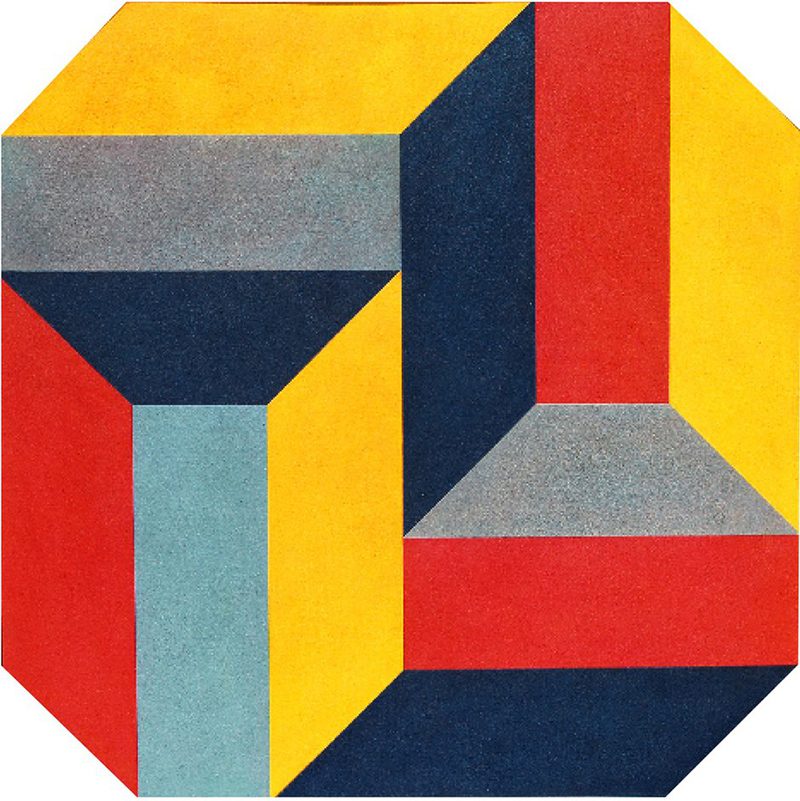

Kenneth Noland was born in Asheville, North Carolina, after graduating from high school in 1942, Noland enlisted in the U.S. Air Force. In 1946 he took advantage of the G.I. Bill by enrolling at Black Mountain College. The highly experimental school was important to many young artists at this time because of its interdisciplinary approach to art education. At Black Mountain College, Ilya Bolotowsky introduced Noland to the Neo-Plasticism and Geometric Abstraction of Piet Mondrian, while Bauhaus artist Josef Albers acquainted him with the work of Paul Klee. Noland paid close attention to Klee’s subtle nuances of color combined with bold contrasts of positive and negative space, which eventually informed Noland’s own art. In 1948, after two years at Black Mountain, Noland traveled to Paris and studied under the Russian sculptor Ossip Zadkine. Noland would eventually rebel against Zadkine’s Cubist teachings, opting for radically simplified color and form. In 1949 he had his first solo exhibition at the Galerie Raymond Creuze in Paris. After a year abroad, Noland returned to the United States. While living in D.C., Noland met and befriended fellow painter Morris Louis. At this time both men were painting in an Abstract Expressionist style, although neither artist was considered a member of the so-called first generation of Abstract Expressionist artists that centered in New York City In 1952 Noland decided to abandon any tendencies to paint in the Abstract Expressionist style and began work on a new set of paintings: the so-called “Targets”. These paintings, also called “Circles”, were his breakthrough works. By 1963 Noland had concluded that he had exhausted the possibilities of his “Circles in a square” format. He wanted to continue to experiment with colors and their interactions, but he needed a different theme with which to work. For the next phase of his career he began his “Chevron” paintings. In 1964 Clement Greenberg curated an exhibition of new art at the Los Angeles Country Museum of Art, including works by Noland as well as by Jules Olitski, Helen Frankenthaler, Ellsworth Kelly, Jack Bush, Frank Stella, Morris Louis, and various others. Attempting to formally categorize this emerging post-Abstract Expressionist art, Greenberg dubbed this group’s work “Post-Painterly Abstraction”. In the late 1960s, Noland switched to using rectangular canvases and horizontal lines in a new series he called “Stripes”, he began playing with scale, color, and form on new levels. He reduced his compositions to a basic formula, parallel horizontal lines of varying widths and colors, running along the entire width of the canvas. In the 1970s and 1980s, Noland made a brief return to chevrons, experimented with color compositions in plaid-like patterns, and, perhaps most importantly, produced several differently shaped canvases. In 1999, Noland began work on his “Mysteries” series of paintings (1999-2002), which was in many respects a return to his beginnings as a formalist abstractionist of the late ‘50s. Using acrylics on paper and unprimed canvas, he once again painted symmetrical circular targets on square supports. His new “Targets”, much like the older ones, were as visually bold as they were deliberately void of subject; however, he wanted to reaffirm their relevancy as the new millennium approached. Noland died at the age of 85, he had lived much of his late life in a quiet community in Maine, where he worked in his studio until his final days.

Kenneth Noland was born in Asheville, North Carolina, after graduating from high school in 1942, Noland enlisted in the U.S. Air Force. In 1946 he took advantage of the G.I. Bill by enrolling at Black Mountain College. The highly experimental school was important to many young artists at this time because of its interdisciplinary approach to art education. At Black Mountain College, Ilya Bolotowsky introduced Noland to the Neo-Plasticism and Geometric Abstraction of Piet Mondrian, while Bauhaus artist Josef Albers acquainted him with the work of Paul Klee. Noland paid close attention to Klee’s subtle nuances of color combined with bold contrasts of positive and negative space, which eventually informed Noland’s own art. In 1948, after two years at Black Mountain, Noland traveled to Paris and studied under the Russian sculptor Ossip Zadkine. Noland would eventually rebel against Zadkine’s Cubist teachings, opting for radically simplified color and form. In 1949 he had his first solo exhibition at the Galerie Raymond Creuze in Paris. After a year abroad, Noland returned to the United States. While living in D.C., Noland met and befriended fellow painter Morris Louis. At this time both men were painting in an Abstract Expressionist style, although neither artist was considered a member of the so-called first generation of Abstract Expressionist artists that centered in New York City In 1952 Noland decided to abandon any tendencies to paint in the Abstract Expressionist style and began work on a new set of paintings: the so-called “Targets”. These paintings, also called “Circles”, were his breakthrough works. By 1963 Noland had concluded that he had exhausted the possibilities of his “Circles in a square” format. He wanted to continue to experiment with colors and their interactions, but he needed a different theme with which to work. For the next phase of his career he began his “Chevron” paintings. In 1964 Clement Greenberg curated an exhibition of new art at the Los Angeles Country Museum of Art, including works by Noland as well as by Jules Olitski, Helen Frankenthaler, Ellsworth Kelly, Jack Bush, Frank Stella, Morris Louis, and various others. Attempting to formally categorize this emerging post-Abstract Expressionist art, Greenberg dubbed this group’s work “Post-Painterly Abstraction”. In the late 1960s, Noland switched to using rectangular canvases and horizontal lines in a new series he called “Stripes”, he began playing with scale, color, and form on new levels. He reduced his compositions to a basic formula, parallel horizontal lines of varying widths and colors, running along the entire width of the canvas. In the 1970s and 1980s, Noland made a brief return to chevrons, experimented with color compositions in plaid-like patterns, and, perhaps most importantly, produced several differently shaped canvases. In 1999, Noland began work on his “Mysteries” series of paintings (1999-2002), which was in many respects a return to his beginnings as a formalist abstractionist of the late ‘50s. Using acrylics on paper and unprimed canvas, he once again painted symmetrical circular targets on square supports. His new “Targets”, much like the older ones, were as visually bold as they were deliberately void of subject; however, he wanted to reaffirm their relevancy as the new millennium approached. Noland died at the age of 85, he had lived much of his late life in a quiet community in Maine, where he worked in his studio until his final days.