TRACES: Rebecca Horn

Today is the occasion to bear mind the German artist Rebecca Horn (24/3/1944-6/9/2024). She is most famous for her body modifications such as “Einhorn”. She was inspired by the works of Franz Kafka and Jean Genet, as well as the films of Luis Buñuel and Pier Paolo Pasolini. A lung complaint forced her to change her way of working, and she began to work with soft materials such as bandages or feathers/springs. Through this column, as a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear mind the German artist Rebecca Horn (24/3/1944-6/9/2024). She is most famous for her body modifications such as “Einhorn”. She was inspired by the works of Franz Kafka and Jean Genet, as well as the films of Luis Buñuel and Pier Paolo Pasolini. A lung complaint forced her to change her way of working, and she began to work with soft materials such as bandages or feathers/springs. Through this column, as a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Efi Michalarou

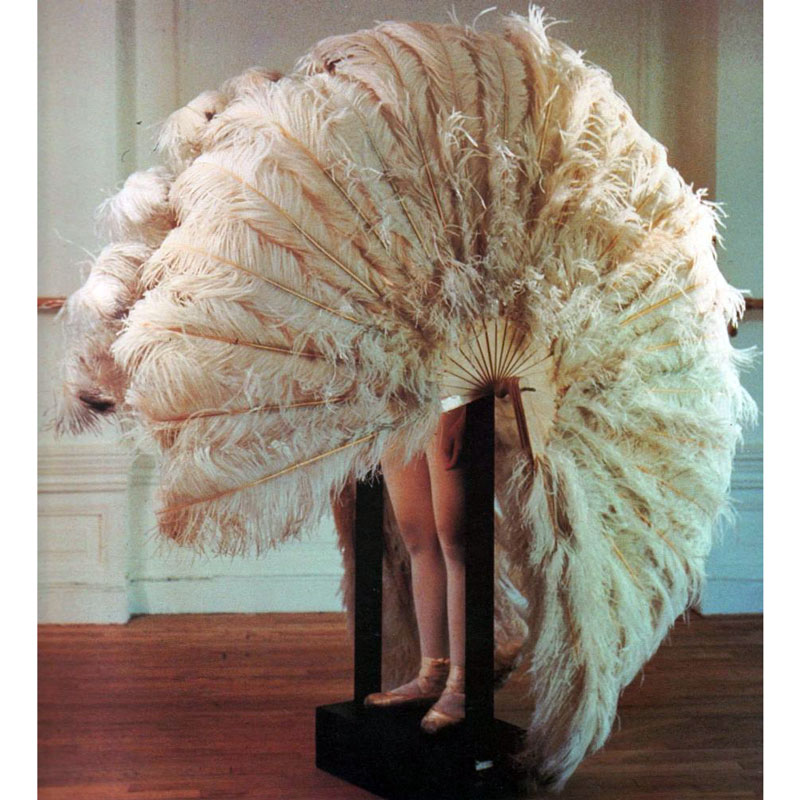

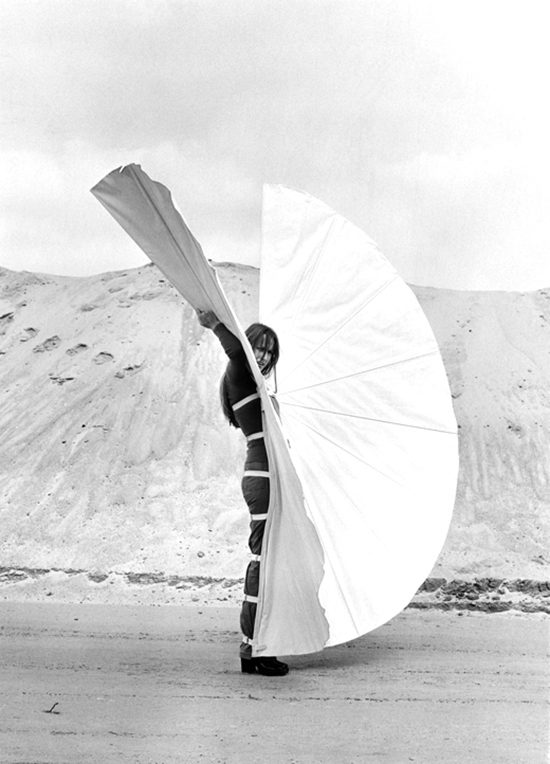

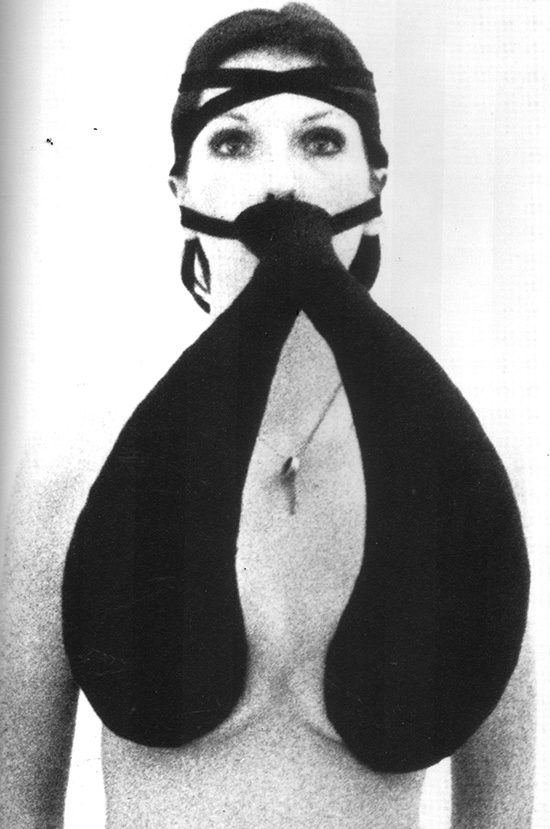

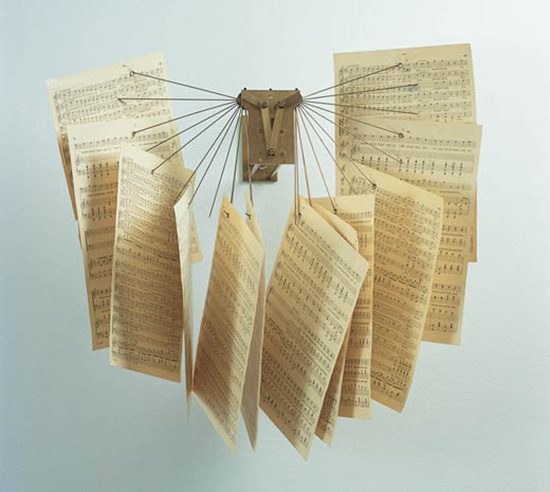

Rebecca Horn was born in Michelstadt, she spent most of her late childhood in boarding schools, at nineteen she rebelled against her parents’ plan of studying economics and decided to study art. In 1963 she attended the Hochschule für bildende Künste Hamburg. In 1964 while working with toxic materials she contracted lung poisoning and was sent to a sanitarium for about a year, during which time she was often bedridden and isolated from the outside world. Tragically, her parents also passed away while she was hospitalized. For two years afterward she continued to live in seclusion. This experience led Horn to experiment with individualized body extensions as a coping strategy. Many of her ideas were visually influenced by the hospital setting, including designs that involve large bandages, body trusses, and prostheses. Her staged performances, which were often produced as films, featured both her and actors in various roles executing specific movements. When incorporated into these studied, often intimate scenes, the objects themselves become imbued with symbolic, mythological power in their relation to the wearer, through which Horn forges ambiguous but weighty narratives. In 1968 Horn produced her first body sculptures, in which she attached objects and instruments to the human body, taking as her theme the contact between a person and his or her environment. She presented “Einhorn” at the 1972 Documenta. Ideas of touch and sensory awareness are explored in the work “Finger Gloves” (1972). One of a series of mechanised sculptures is “Concert for Anarchy” (1990). A grand piano is suspended upside down from the ceiling by heavy wires attached to its legs. It hangs solidly yet precariously in mid-air, out of reach of a performer, high above the gallery floor. In the ‘80s and ‘90s huge installations were created out of and dedicated to places charged with political and historical importance. With her kinetic sculptures, the artist releases and rediverts the weight of the past on these physical spaces: as for example in “Concert in Reverse” (1997) in Münster, an old municipal tower turns out to be an execution site for the Third Reich: or in Vienna, with the “Tower of the Nameless” (1994), where she sets a monument to the refugees from Balkan states in the form of a tower with mechanically playing violins. In Weimar, Europe’s city of culture 1999, the “Concert for Buchenwald” was composed on the premises of a former tram depot. The artist has layered 40 metre long walls of ashes behind glass, as archives of petrifaction. In “Mirror of the Night” (1998), at a derelict synagogue in Cologne, she uses the energy of writing, textured to counter historical amnesia.

Rebecca Horn was born in Michelstadt, she spent most of her late childhood in boarding schools, at nineteen she rebelled against her parents’ plan of studying economics and decided to study art. In 1963 she attended the Hochschule für bildende Künste Hamburg. In 1964 while working with toxic materials she contracted lung poisoning and was sent to a sanitarium for about a year, during which time she was often bedridden and isolated from the outside world. Tragically, her parents also passed away while she was hospitalized. For two years afterward she continued to live in seclusion. This experience led Horn to experiment with individualized body extensions as a coping strategy. Many of her ideas were visually influenced by the hospital setting, including designs that involve large bandages, body trusses, and prostheses. Her staged performances, which were often produced as films, featured both her and actors in various roles executing specific movements. When incorporated into these studied, often intimate scenes, the objects themselves become imbued with symbolic, mythological power in their relation to the wearer, through which Horn forges ambiguous but weighty narratives. In 1968 Horn produced her first body sculptures, in which she attached objects and instruments to the human body, taking as her theme the contact between a person and his or her environment. She presented “Einhorn” at the 1972 Documenta. Ideas of touch and sensory awareness are explored in the work “Finger Gloves” (1972). One of a series of mechanised sculptures is “Concert for Anarchy” (1990). A grand piano is suspended upside down from the ceiling by heavy wires attached to its legs. It hangs solidly yet precariously in mid-air, out of reach of a performer, high above the gallery floor. In the ‘80s and ‘90s huge installations were created out of and dedicated to places charged with political and historical importance. With her kinetic sculptures, the artist releases and rediverts the weight of the past on these physical spaces: as for example in “Concert in Reverse” (1997) in Münster, an old municipal tower turns out to be an execution site for the Third Reich: or in Vienna, with the “Tower of the Nameless” (1994), where she sets a monument to the refugees from Balkan states in the form of a tower with mechanically playing violins. In Weimar, Europe’s city of culture 1999, the “Concert for Buchenwald” was composed on the premises of a former tram depot. The artist has layered 40 metre long walls of ashes behind glass, as archives of petrifaction. In “Mirror of the Night” (1998), at a derelict synagogue in Cologne, she uses the energy of writing, textured to counter historical amnesia.