PRESENTATION:Chris Ware-Drawing is Thinking

Chris Ware is one of the most innovative artists in modern comic books. His drawings touch us because they deal with human existence with great depth, his works explore themes of social isolation, emotional torment and depression. He tends to use a vivid color palette and realistic, meticulous detail. His lettering and images are often elaborate and sometimes evoke the ragtime era or another early 20th-century American design style.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: CCCB Archive

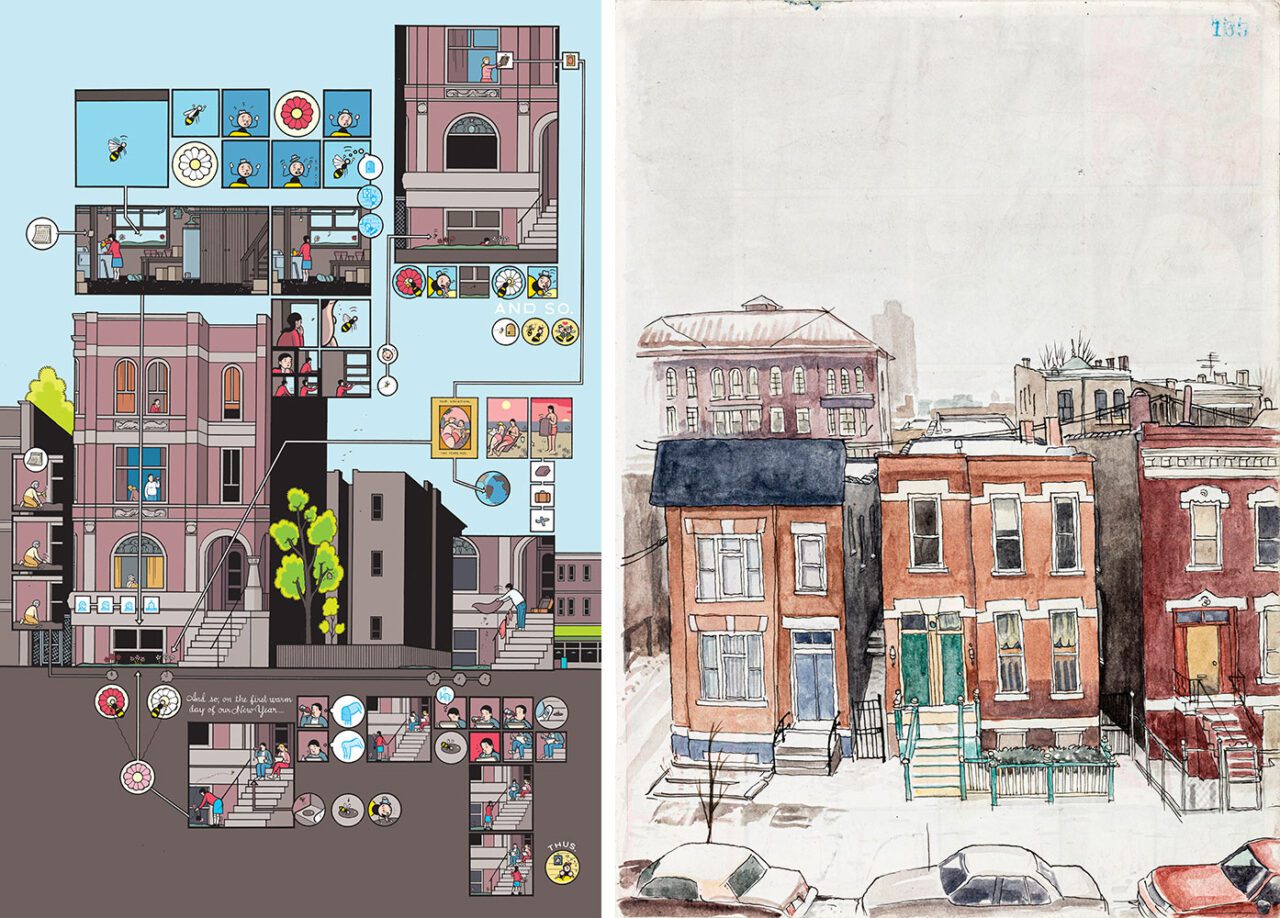

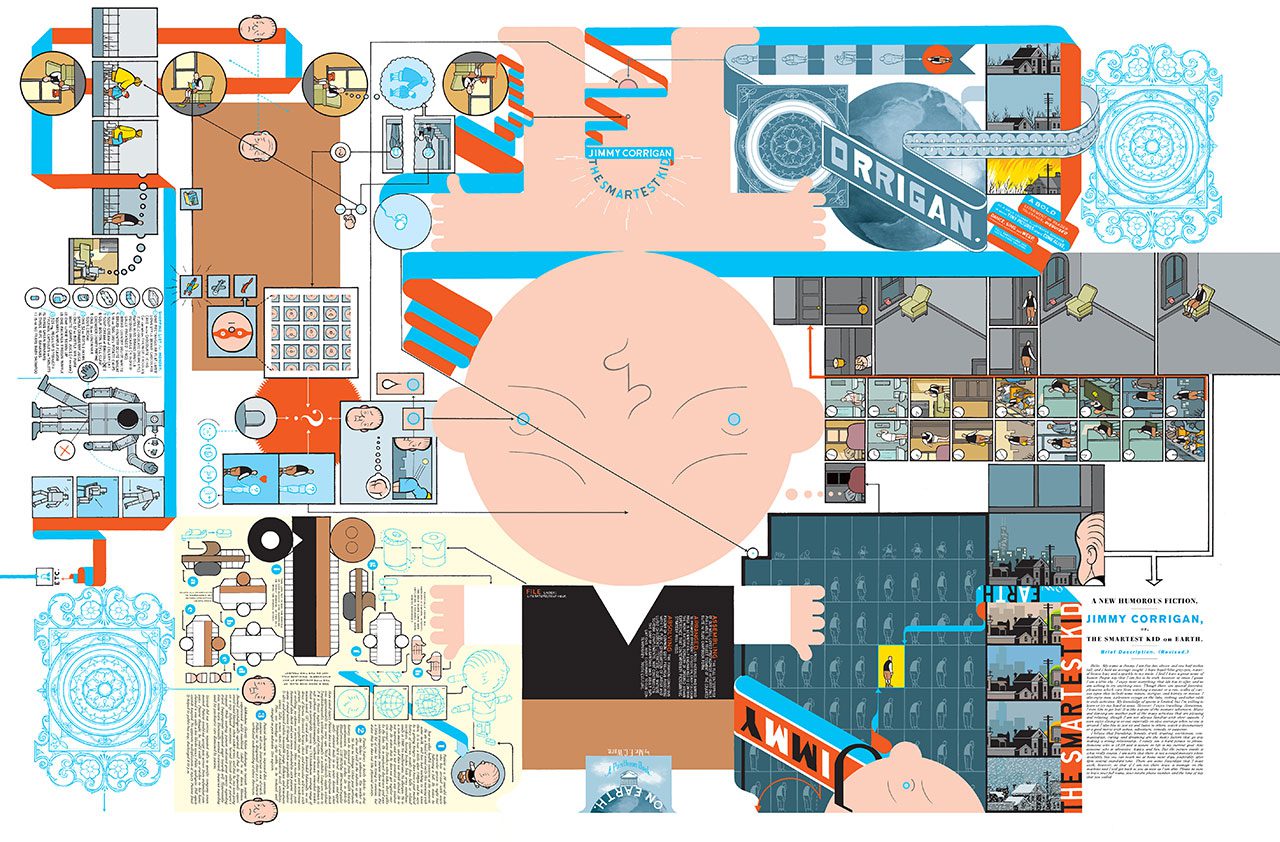

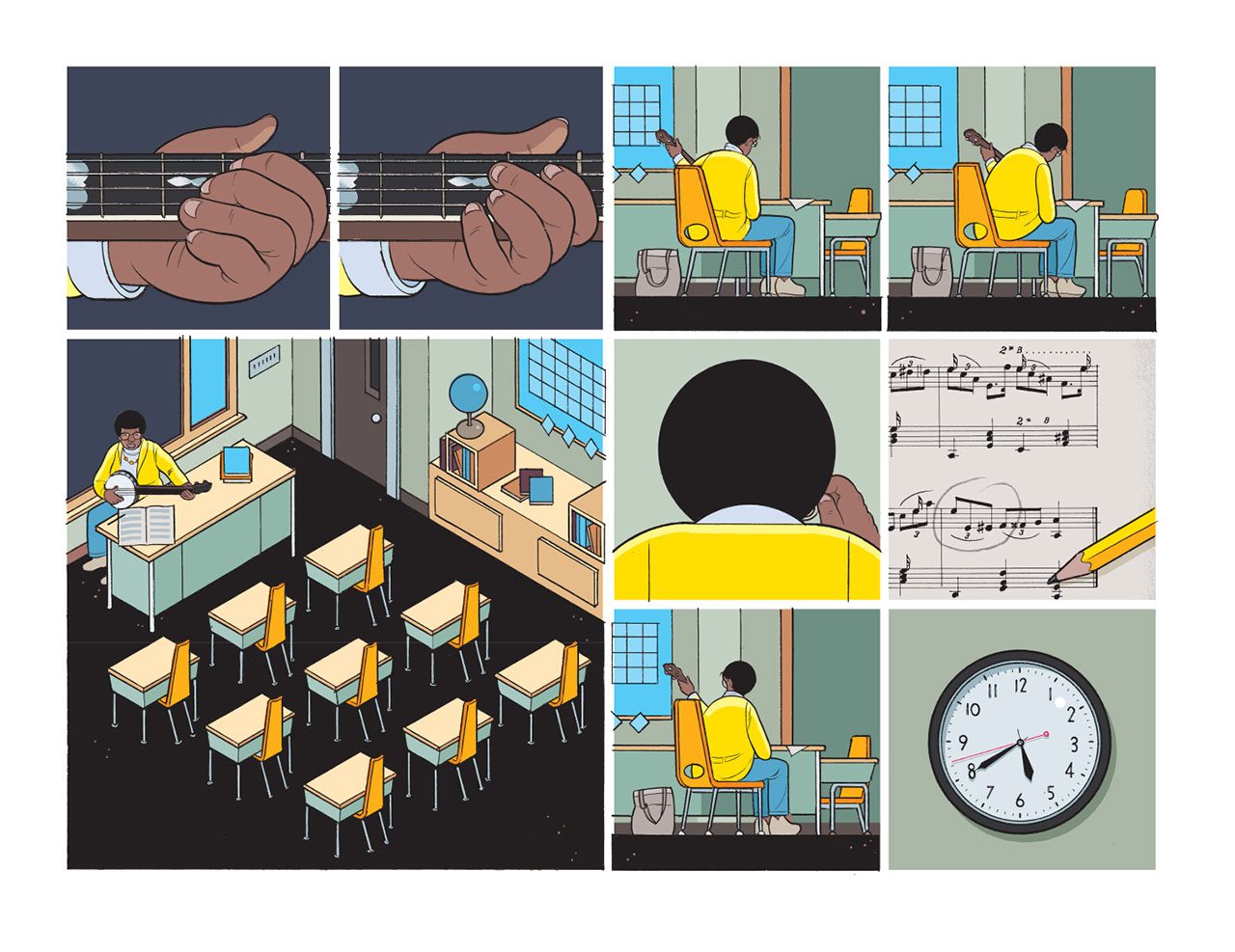

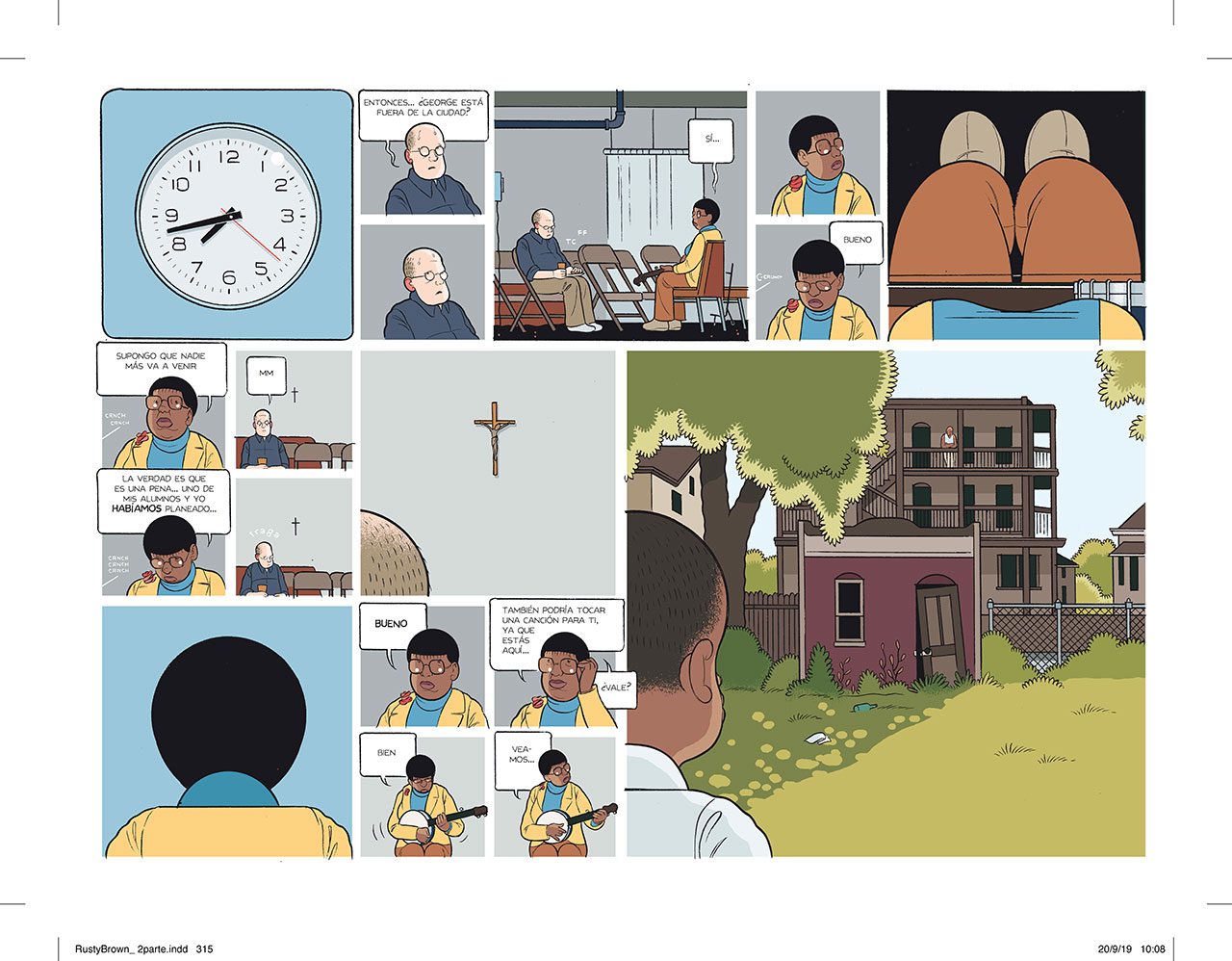

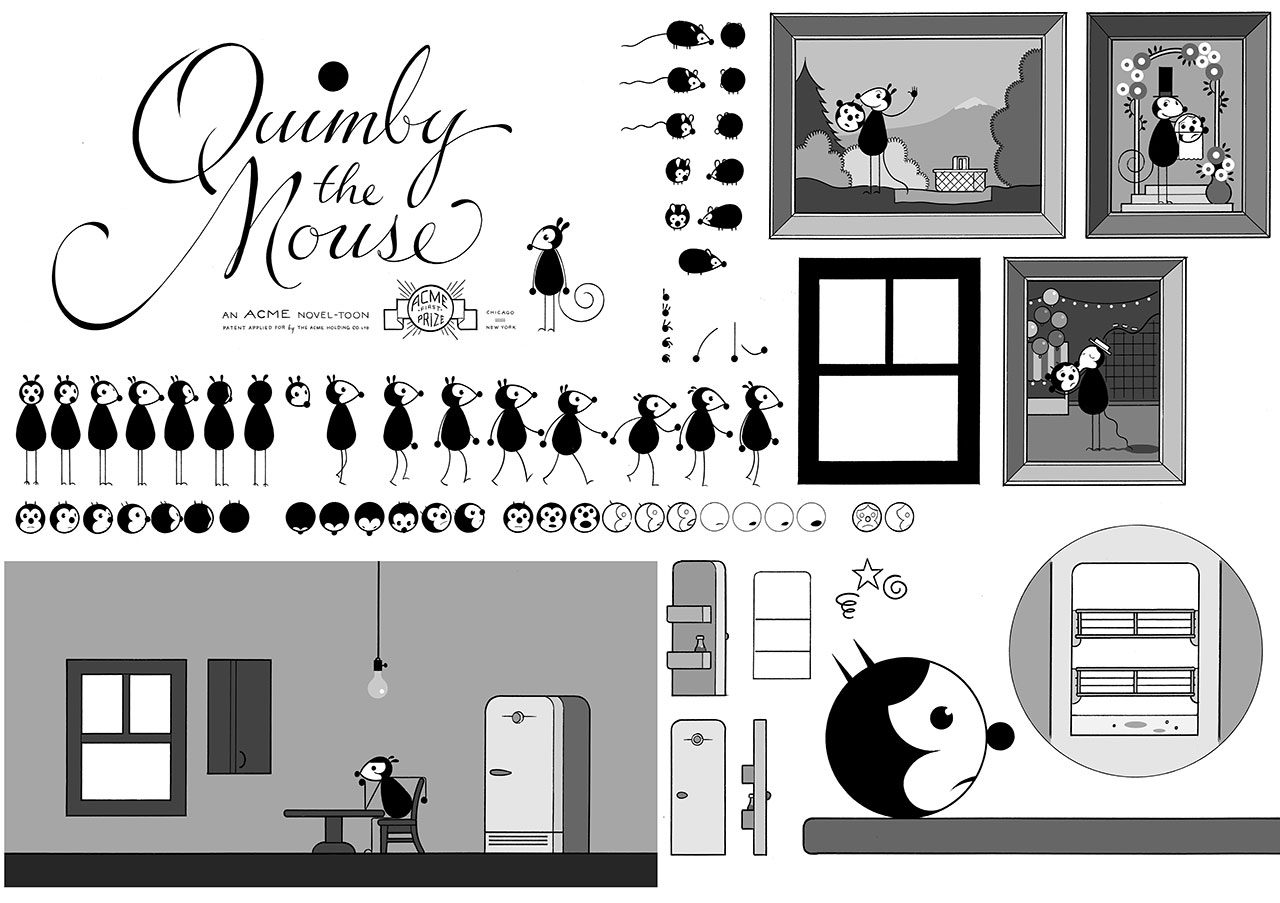

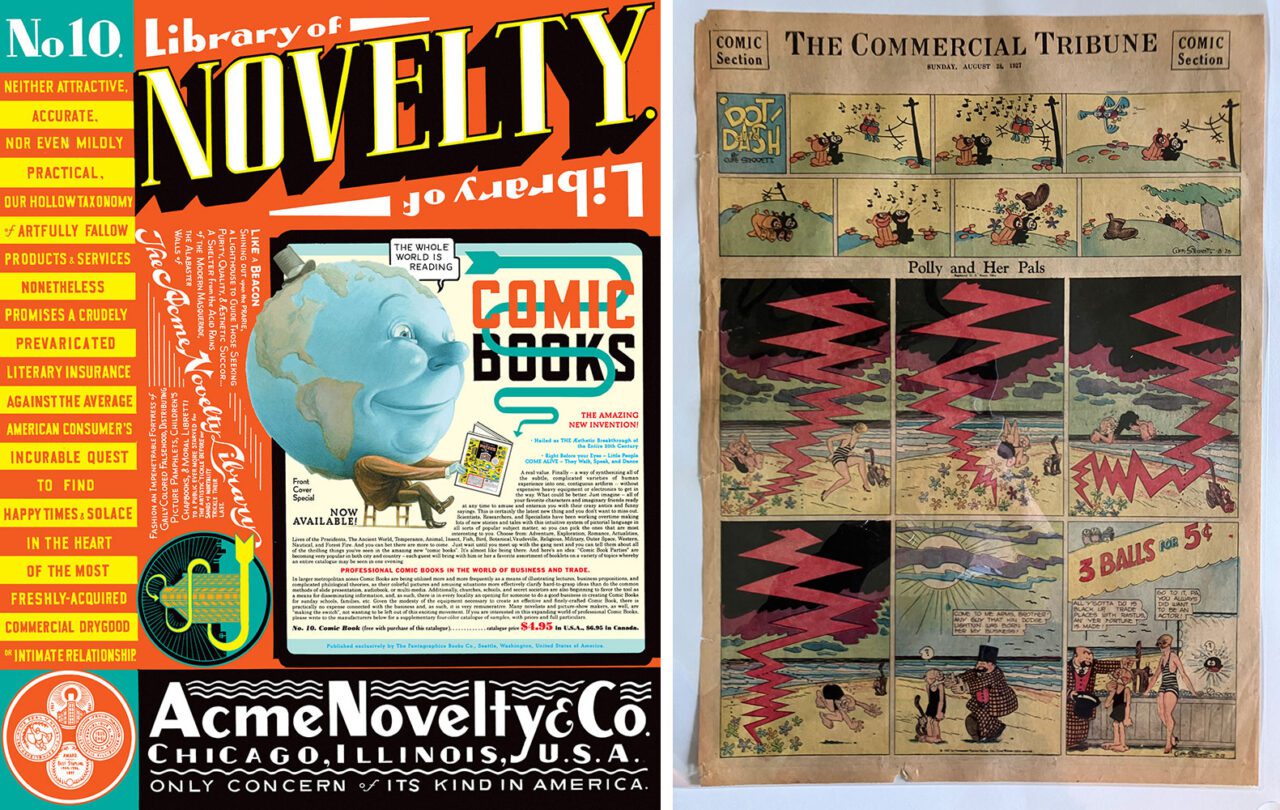

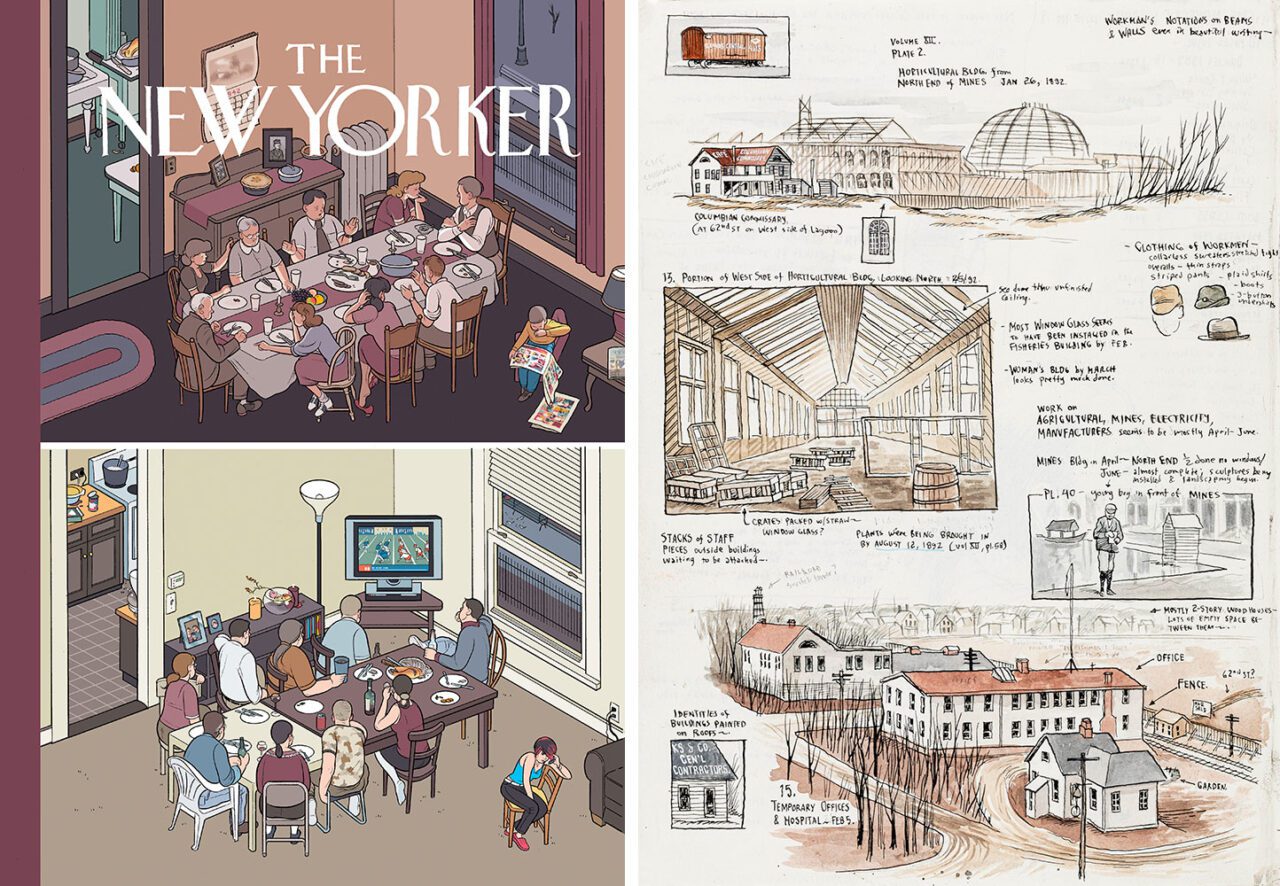

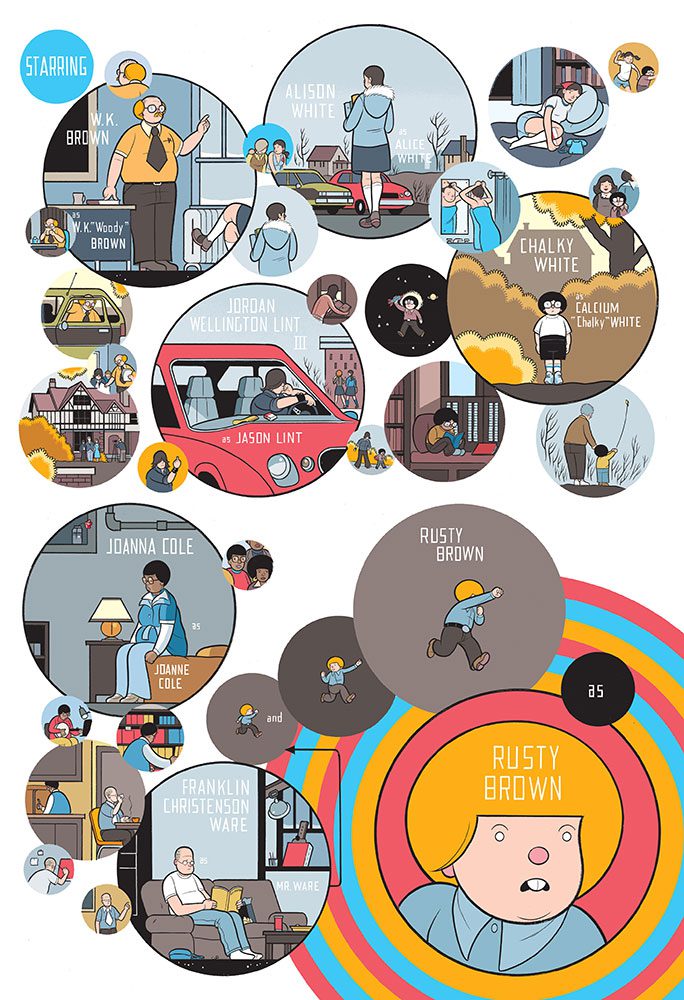

The exhibition “Drawing is Thinking” reviews the work and artistic thinking of Chris Ware. Chris Ware has been drawing or, as he says, writing with vignettes, since he was small. Ware has experimented and innovated with comic book language and narrative throughout his life: from sketchbooks, to the iconic frontpage covers of The New Yorker, to his three essential works: “Jimmy Corrigan, The Smartest Kid on Earth”, “Building Stories” and “Rusty Brown”. The exhibition invites us to take a chronological look at the work of a master of the comic strip, with original pieces, animations, objects and sculptures, highlighting Ware’s invention of language and into the creative universe of a meticulous, artisan, emotional artist, influenced by the origins of the comic book, ragtime music and architecture, who has brilliantly narrated human emotions, racism, consumerism and the effects of politics on everyday life. For Ware, “drawing is a way of thinking”, because drawing connects us with thought and memory. The work of Chris Ware is based on a thorough knowledge of the his- tory of comic books, calling for the expressive freedom of their origins when, before a dominant language was consolidated, in the US they experienced a bubbling up of forms and possibilities. Ware occasion- ally becomes a historian and comic-book theorist, and, as an editor, salvages works from that golden age, such as George Herriman’s Krazy Kat and Frank King’s Gasoline Alley. Herriman, King and Cliff Sterrett, author of the Polly and Her Pals series, were the main references for Ware, who was inspired by their formal and narrative solutions to reactivate all the potential of the medium. Herriman’s poetic surrealism, King’s humanist realism and Sterrett’s dialogues with forms of avantgarde art come together in Ware in a transformative formula that was to define the future of the comic book. The first issue of Acme Novelty Library appeared in 1993, in a golden age of American independent comics when many new authors controlled their own titles and turned the pages into a laboratory for experimentation. Acme Novelty Library was the project that went furthest, with issues that radically changed format and ventured into a postmodernity firmly committed to its roots in popular culture. All of Ware’s main characters were given life in these pages and gradually integrated into increasingly complex narratives. The last issues of Acme Novelty Library were self-published by Ware, taking the form of object books where the covers, spines and textures were part of the message, and where the essential meaning added fragments of the works in progress, Building Stories and Rusty Brown. “Jimmy Corrigan, the Smartest Kid on Earth” is a story about loneliness, abandonment and complex family relationships, with a strong emotional and autobiographical component. Published as a book in 2000, Chris Ware said that the four or five hours it took to read was the amount of time he had spent with his father, who left the family when Ware was very small and didn’t get in touch until many years later. An imaginary town in Michigan in 1993 and the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893 provide the main settings for this story that traces a family tree marked by abandonment With a great deployment of resources, the work excels in its representation of dead time, the harmony of the narrative transitions and the gestural precision of the characters. “Quimby the Mouse” contains cartoons in which Chris Ware pays homage to the freest forms of original comics that have most influenced him, especially George Herri- man’s Krazy Kat. They feature a two-headed mouse or the odd couple made up of a mouse and a cat’s head. Ware created most of these pages when he was studying at Austin, and their autobiographical substratum is nostalgia for the house where he spent his adoles- cence with his grandmother. Memory, an internalized sense of loss and a resistance to forgetting coexist in the adventures of Sparky and Quimby with radical formal and metalinguistic work. The comic strip is a visual message where images must be read as signs. The extremely simplified treatment of the characters likens them to typographic fonts or musical notes from a score that the reader’s gaze activates and sets in motion. As a lover of old buildings and highly critical of the more formalist as- pects of modern architecture, Chris Ware explored the similarities be- tween the construction of a building, the design of a page and the articulation of a story in one of his most unique and complex projects. The product of 10 years of work, “Building Stories” (2012) is a box containing 14 editorial objects in different formats designed to be read in any order: cloth-bound books, broadsheet newspapers, comic books, strips that form narrative loops, gameboards and others. The centre of gravity of this labyrinth of intertwined destinies and stories is an old Chicago apartment building with a voice of its own. The theme of loss runs throughout the work, and Ware displays a maturity that allows him to capture all the subtleties and complexity of a whole existence, giving equal importance to surroundings, objects, thoughts, emotions and things never said. “Rusty Brown” is a monumental work and a veritable human (tragi)comedy in which Ware extends his narrative vocabulary to explore uncharted territories in comic-strip language. The first part, the only one published, comprises four long chapters. The opening chapter introduces the main characters in a description of the first day at high school of siblings Chalky and Alison. Ware plays skilfully with time and parallel actions, giving himself the unflattering role of a pompous art teacher. Chapter two centres on the youth of Rusty Brown’s father, marked by a tortuous discovery of sexuality and his vain aspirations as a science-fiction writer. The remaining two chapters are the great discoveries of the project. One portrays the life of former school bully Jordan Lint and gives visual form to the Joycean stream of consciousness. The other portrays Joanna Cole, a lonely African-American banjo-loving teacher, with the spotlight on the true essence of Ware’s art: the generosity of his humanistic view and the strength of empathy to make fiction an instrument of understanding. The exhibition concludes with a collective creation space inspired by one of Chris Ware’s most iconic works, Building Stories, transferring the story to Barcelona. A huge storyboard of blank vignettes covers the walls. Anyone can draw actions, memories, dreams or details in them and take part in the construction of a story based on Ware’s techniques. A proposal of La Gossa comic school (Alfredo Borés and Berta Embún), with contributions by cartoonists Cristina Daura, Nadia Hafid, Sergi Puyol and Marc Torices.

Photo: Chris Ware, Courtesy the artist and CCCB

Info: Curator: Jordi Costa, CCCB (Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona). Montalegre 5, Barcelona, Spain, Duration: 3/4-9/11/2025, Days & Hours: Tue-Sun 10:00-20:00, www.cccb.org/en