PRESENTATION: Jack Whitten

Born in 1939, Jack Whitten is celebrated for his innovative processes of applying paint to the surface of his canvases and transfiguring their material terrains. Although Whitten initially aligned with the New York circle of abstract expressionists active in the 1960s, his work gradually distanced from the movement’s aesthetic philosophy and formal concerns, focusing more intensely on the experimental aspects of process and technique that came to define his practice.

By Dimitris empesis

Photo: MoMA Archive

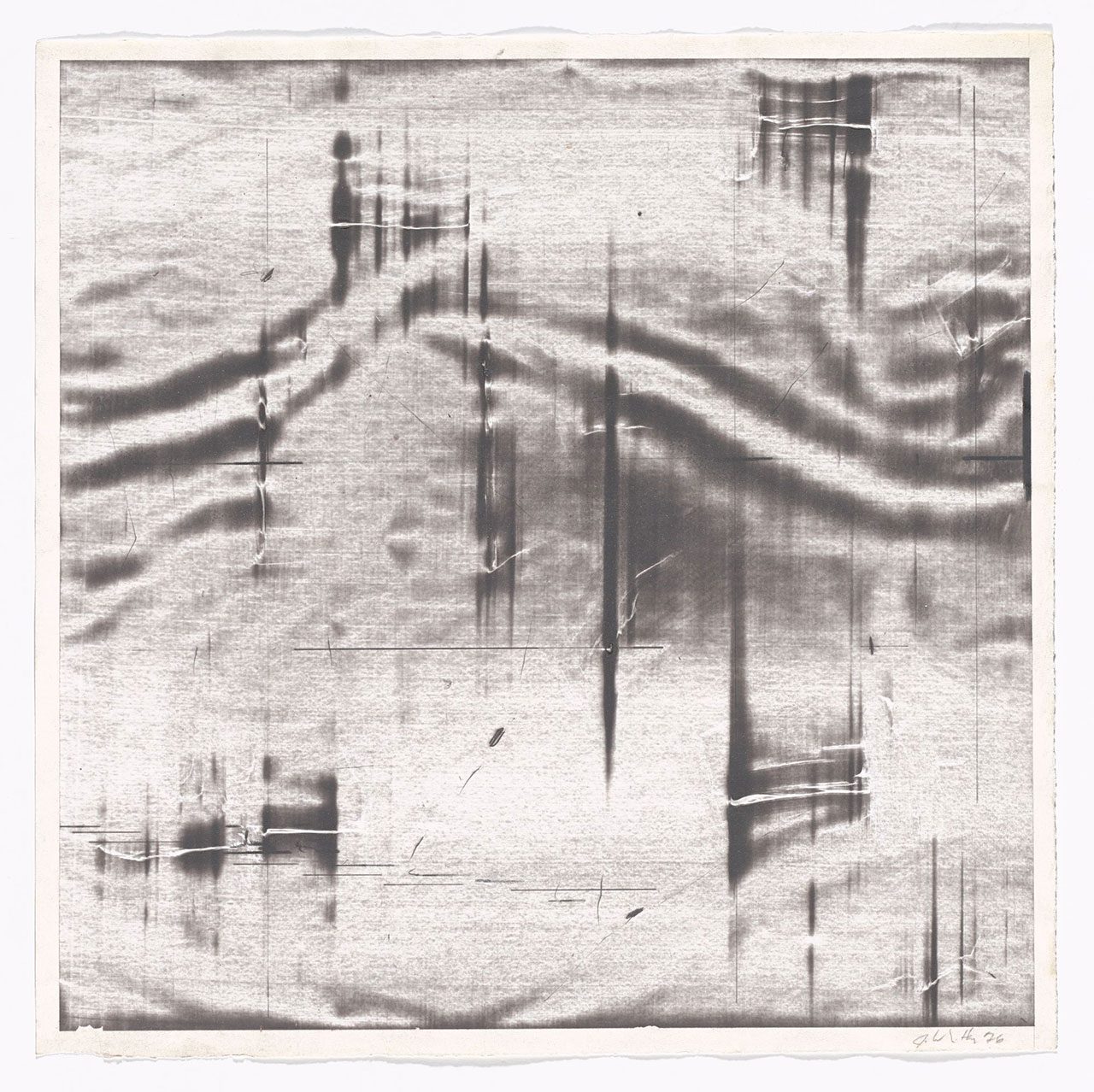

“The Messenger” is the first comprehensive retrospective dedicated to the groundbreaking art of Jack Whitten, the exhibition explores the full range of Whitten’s innovative art over his nearly six-decade career, showing more than 175 works from the 1960s to the 2010s, including paintings, sculptures, rarely shown works on paper, and archival materials. Together, these works reveal how Whitten overturned the tenets of modern art-making to become one of the most important artists of our time. In the 1960s, Jack Whitten had an identity crisis. The son of a seamstress and a coal miner, he had been the first person in his family to attend college, studying pre-medicine at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. But in 1959, he abruptly changed course, moving to Louisiana to pursue art. He also began participating in Civil Rights demonstrations. The violent backlash he experienced prompted him to leave the segregated South. Whitten earned a scholarship to the Cooper Union in New York in 1960. He plunged into a world of artists, writers, dancers, and jazz musicians—from Willem de Kooning to Jacob Lawrence and John Coltrane—becoming fascinated by the gestural brushstrokes of Abstract Expressionism. He soon invented his own ways of making: producing ghostly figures that melt into abstract, filmic shadows; vibrant “gardens” of faces and flora, dedicated to Martin Luther King Jr.; and bursts of color that evoke war, hallucination, or science fiction. Whitten was haunted by his past, by histories of racial violence and the turmoil of the present. But he began creating forms for the future. At the start of a new decade, Whitten had a breakthrough. He stopped making figurative art and got rid of his paintbrushes. “1970 was the turning point,” he recalled. “The studio became a laboratory designed to experiment with acrylic paint.” The medium, a recent innovation made from plastic, offered a vastly expanded range of color, texture, and handling. Seizing the opportunity, Whitten invented tools and techniques that were entirely new to the history of Western art. From an Afro-comb to a twelve-foot-long wooden rake, which he called the “Developer” in reference to photography, novel implements were maneuvered by the artist to pull layers of acrylic paint across canvas laid on his studio floor in one sweeping movement. With each pull, Whitten revealed carefully calibrated underlayers in startling hues. Some of the resulting works evoke glowing screens or “energy fields,” as the artist called them; others look like an almost photographic blur, as if blending painting and technology. Whitten often dedicated these works to specific people, from his daughter to the Civil Rights leaders Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. But his pictures were no longer of faces or figures; he had made the turn to abstraction. In these paintings, he said, “Memory is trapped in the material”. Over the course of one extraordinary year, between 1973 and 1974, Whitten accelerated his experiments in preparation for an exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. It was his first solo museum show and one of a few afforded to Black artists in New York at the time. He infused increasingly sophisticated and unusual materials into acrylic paint, including chemicals to slow or speed up its drying time or alter its liquidity. He built up many layers of paint in different colors, then dragged his Developer tool across the surface with a single, powerful three-second pull. The effect is one of speed, or the blur of a camera in motion, as the top layer of paint is stretched and smeared to reveal endless, shifting layers below. Whitten could never quite know what would appear after his one shot, his one “photographic” take. For Whitten, these creative risks, which he called “gambling,” upended conventional ways of seeing—and being in—the world.“ The more I paint the more I see,” he wrote in his studio log, in 1973. Whitten’s pictures suggest the ways in which struggles for freedom and power could emerge through artistic experimentation. In 1975, Whitten made yet another sea change in his art. His colorful “blur” canvases gave way to a new series of paintings named after the letters of the Greek alphabet and inspired by the summers he spent in Crete with his family. The artist had also attended a residency at the Xerox Corporation in 1974, and became fascinated by the heat-sensitive, black powder used for the company’s cutting-edge photocopier technologies. He whittled his palette down to black and white, but from these two colors he produced an explosion of new optical effects. Using his Developer tool and other implements, Whitten continued to innovate with acrylic paint. He found in its plastic qualities a way to achieve novel forms of illusion and relief, gradually reintroducing color to create dazzling, almost holographic surfaces. Whitten’s works in this period undo any clear distinction between black and white, up and down, forward and backward, color and uncolored, machine and human. By challenging these binary oppositions, Whitten also sought a greater understanding of his own identity.

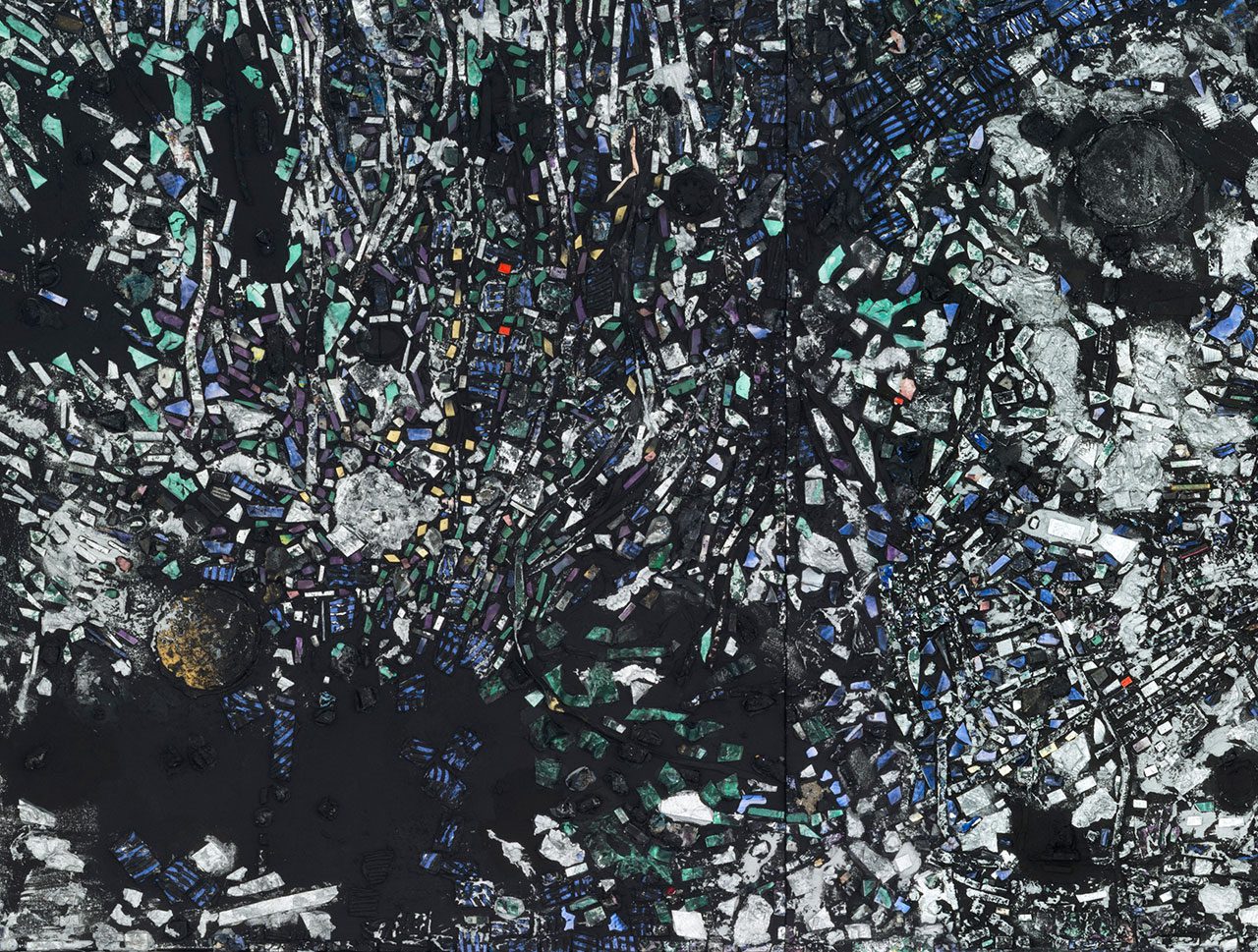

Whitten wanted to reimagine the history of art—and to expand its reach. By linking his work to sources such as African sculpture, which he called the “DNA” of all art, he hoped to overturn the traditions of Western culture and create something new. This would be a revolution not through moral commandments or slogans, but by changing perception itself. “My paintings are designed as weapons,” the artist said. “Their objective is to penetrate and destroy the Western aesthetic.” “Dead Reckoning I”( 1980) appears as one such weapon, suggesting both a fighter plane’s navigational system and a target sight. In 1980, Whitten’s SoHo studio burned down in a devastating fire. The artist took years to rebuild, and did not make any work until 1983. When he emerged, he began experimenting with a wholly new way of using acrylic paint: creating plaster molds of objects and surfaces found in New York streets, from the ridged bottoms of bottles to manhole covers and metal grates, and then filling them with acrylic paint to cast sculptural reliefs. Whitten called these works “skins,” and they served as an index of the hardness and hardships of the city around him. But they also allowed him to find a way to rebuild, to bring the world back into his work. Around 1990, Whitten suddenly invented yet another form of art. He created sheets of dried acrylic paint, spread flat in trays or on tables to dry, and used a razor blade to carve, slice, or shatter the hardened acrylic into small tiles. Each tile could be combined with others to form sprawling, intricately constructed abstract paintings. These puzzles of visual information suggest both ancient Byzantine mosaics and digital images. As the artist noted, “When I break it down into these little bits that I work with, it’s like a pixel. Like each tesserae is a piece of light. . . . The message is coded into the process.” The tiles also evoke the multipart construction of African sculpture, which Whitten likened to the infinitely combinable bits of digital technology, or a kind of universal code. Many of these mosaic paintings mark specific lives and events, from the personal to the global, from celebration to catastrophe. “Fifth Gestalt (Coal Miner)”” and “Sixth Gestalt (The Seamstress)” (1992) are dedicated to Whitten’s parents. “9.11.01” (2006) is a colossal monument to the victims of the attacks of September 11, 2001, which the artist witnessed from his studio in Lower Manhattan. Whitten saw these memorials as a means of confronting history, but also as posing a renewed identity, a new way of being, in a world that continually seemed to be on the verge of breaking down. Whitten began his “Black Monoliths” in 1988, celebrating influential Black figures throughout history. The series title refers to a monumental rock formation near his house in Greece, which prompted him to create the first of the paintings in honor of James Baldwin, the writer and Civil Rights activist who had died in 1 9 8 7. Whitten later dedicated works to W. E. B. Du Bois, Maya Angelou, Ornette Coleman, Muhammad Ali, and others. Rather than depicting a face or likeness, Whitten’s “Black Monoliths” are abstract—the paint infused with materials such as coal dust, pearlescent powder, and octopus ink to evoke or even embody the works’ subjects. The kaleidoscopic mosaics and reliefs suggest individual elements or fragments coming together: constellations of stars, glittering gems, waves of sound, or masses of earth. Whitten thought of his art as a “portal” to other worlds. Fascinated by science and technology he hoped his work might bend space, light, and time to create new sensations. He continued to explore these phenomena in his last decades, constantly revising and renewing his invented form of acrylic mosaics and incorporating ever more far-flung materials and colors into his paintings, sculptures, and drawings. These works suggest subatomic particles jostling with energy, the interface of a smartphone, or gateways to space travel. For Whitten, these forms were not an escape but a reckoning with the effects of technology: “The modern technological society depends upon the fast movement of vast amounts of complex diversified data; this exerts extreme psychological pressures upon each of us. Artists continually invent ways to deal with these pressures as a means of survival. We are society’s pressure gauge.” Whitten made sculptures every summer, beginning in the mid- 1960s in New York and across his life during annual trips to Crete, Greece. Featured throughout the exhibition and gathered here in a focused group, these works consist of carved and joined wood, often in combination with found materials including bone, marble, paper, glass, nails, fishing line, and computer parts. They were inspired by the arts of Africa and the ancient Mediterranean, and, like his acrylic mosaics, bring together disparate fragments in a new whole. For Whitten, this process of reconstruction was core to all his art. It was a way of building back from a history of dispossession.

Photo: Jack Whitten. Mirsinaki Blue. 1974. Acrylic on canvas, 62 1/8 × 72 1/8″ (157.8 × 183.2 cm). Collection of the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University. Gift of Leonard and Ruth Bocour. © 2024 Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University

Info: Curators: Michelle Kuo, Helena Klevorn, Curatorial Assistants: Dana Liljegren, Eana Kim, David Sledge, Kiko Aebi, MoMA (Museum of Modern Art), 11 West 53 Street, Manhattan, New York, NY, USA, Duration: 23/3-2/8/2025, Days & Hours: Mon-Thu & Sat-Sun 10:30-17:30, Fri 10:30-20:30, www.moma.org/