ART CITIES:Paris-Difference and Repetition

Conceived in homage to the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze, who from the early 1950s until his death in 1995, wrote on philosophy, literature, film, and fine art, the exhibition “Difference and Repetition” presents a conversation between works by artists who have challenged the conventions of form, material, and perception, highlighting the evolution of their practices. the exhibition gathers defining works by key postwar figures.

By Efi MIchalarou

Photo: Gagosian Archive

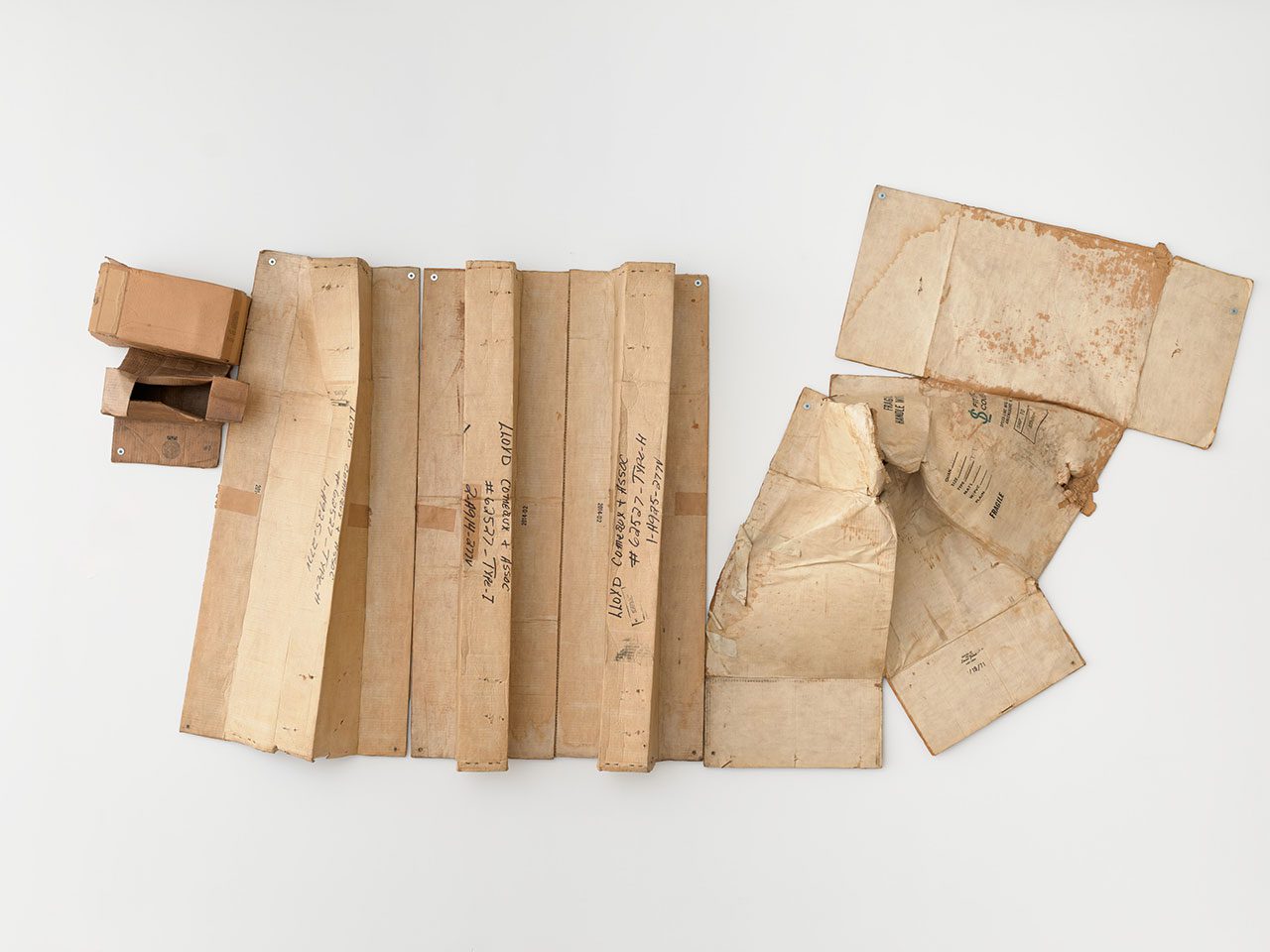

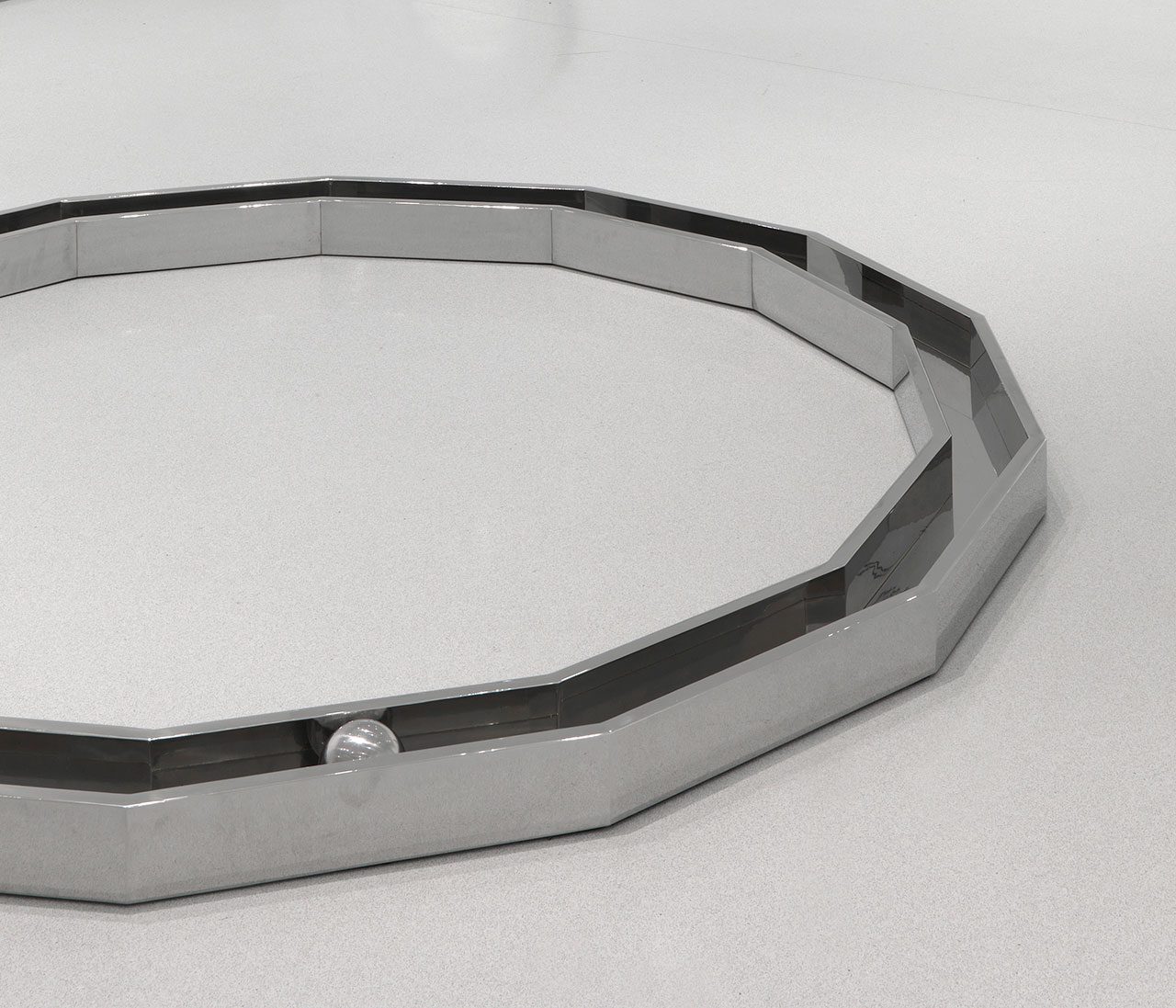

“Difference and Repetition” reveals how repetition in art can redefine perceptual and formal possibilities, examining how artists have employed seriality, variation, and accumulation to destabilize conventional patterns of sight and thought. Picasso’s declaration “In my case, a picture is a sum of destructions” resonates with Deleuze’s thinking. Parallelling the philosopher’s inquiries into differentiation and iteration is Richard Serra’s credo that “Repetition is the ritual of obsession”. Pablo Picasso’s turn to sculpture, Donald Judd’s modular and serial structures, Richard Serra’s insistence on process and his relentless exploration of materiality, and Walter De Maria’s durational works and sculptures demonstrate that repetition is never static, but rather a force of renewal. Lucio Fontana’s “Concetto spaziale: works are pierced, opening the picture plane up to infinite space, while Piero Manzoni’s “Achrome” series negates color, representation, and allusion to emphasize material presence. Robert Rauschenberg and Mario Merz radically reconfigure everyday objects in their art, whereas Andy Warhol’s multiplication of images displaces their received meanings in favor of new interpretations. Engaging with Deleuze’s philosophical framework, The exhibition is a timely reflection on the cyclical nature of artistic innovation and the shifting relationships between past and present. Walter De Maria bridged multiple movements of artistic practice that blossomed in the 1960s creating interactive sculptural installations and providing conceptual underpinnings to larger-scale sculptural work. In later projects he also connected viewers to nature by either embedding visual elements in nature itself, or by bringing components of nature inside gallery spaces. His most ambitious works were not only physically large-scale but also extreme in terms of exhibition duration – some lasting decades, whether indoors or out, conversely some were exceptionally ephemeral because they were exposed to the elements. His active participation in non-visual musical performances were similarly minimalist and large-scale and helped lay the foundations for later generations of musical performers using those characteristics. The career of Lucio Fontana spans some of the most tumultuous decades of the 20th century, from the build up to World War I to the aftermath of World War II and the onset of the Cold War. Trained initially as a sculptor, Fontana rejected the traditional constraints of particular artistic materials and techniques, choosing instead to invent his own media and methods in response to the rapidly changing world he inhabited. Fontana reinterpreted the physical and theoretical limits of art by considering art works as concepts of space, often using surprising gestures that created holes and cuts in canvases to reveal unseen spatial regions. Fontana embraced paradoxes, destroying physical and intellectual traditions in order to create new discoveries. Donald Judd was an American artist, whose rejection of both traditional painting and sculpture led him to a conception of art built upon the idea of the object as it exists in the environment. Judd’s works belong to the Minimalist movement, whose goal was to rid art of the Abstract Expressionists’ reliance on the self-referential trace of the painter in order to form pieces that were free from emotion. To accomplish this task, artists such as Judd created works comprising of single or repeated geometric forms produced from industrialized, machine-made materials that eschewed the artist’s touch. Judd’s geometric and modular creations have often been criticized for a seeming lack of content; it is this simplicity, however, that calls into question the nature of art and that posits Minimalist sculpture as an object of contemplation, one whose literal and insistent presence informs the process of beholding. Piero Manzoni was an Italian of noble birth now best known for canning and selling his own excrement in the name of art. Irreverent, subversive and committed to the tearing down of the established rules of artistic production, Manzoni’s body of work spans monochromatic paintings, sculptures, and conceptual art objects, all of which maintain a sense of humour and mischievous satire. Despite this attitude and generally prankish demeanour, the ideas outlined by Manzoni and his use of the body (both his own and others’) as a medium through which to create art has proved to be immensely influential after his unexpected death at the age of 29. Performance, Land and Conceptual Art movements have all built on aspects of his work and persona, expanding on key concepts and profoundly altering the development of modern artistic practices in doing so.

During his long career, Mario Merz created sculptures, paintings, photographs, and even videos and was one of the first contemporary artists to develop installation art in the 1960s.He did not believe in distinctions between nature and culture, and moved experimentally from one technique to another. His works make use of a variety of everyday materials and motifs—ranging from metal rods to glass fragments, from fresh fruit to bundles of branches, from piles of newspapers to neon tubes, from words to numbers. While creating dense and “material ” paintings as early as the mid-1950s in Turin—paintings that often depict natural elements such as leaves or animals —Merz emerged as a leading figure in the Arte Povera movement around 1967. Pablo Picasso was the most dominant and influential artist of the first half of the 20th century. Associated most of all with pioneering Cubism, alongside Georges Braque, he also invented collage and made major contributions to Symbolism and Surrealism. He saw himself above all as a painter, yet his sculpture was greatly influential, and he also explored areas as diverse as printmaking and ceramics. Finally, he was a famously charismatic personality; his many relationships with women not only filtered into his art but also may have directed its course, and his behavior has come to embody that of the bohemian modern artist in the popular imagination. Considered by many to be one of the most influential American artists due to his radical blending of materials and methods, Robert Rauschenberg was a crucial figure in the transition from Abstract Expressionism to later modern movements. One of the key Neo-Dada movement artists, his experimental approach expanded the traditional boundaries of art, opening up avenues of exploration for future artists. Although Rauschenberg was the enfant terrible of the art world in the 1950s, he was deeply respected and admired by his predecessors. Despite this admiration, he disagreed with many of their convictions and literally erased their precedent to move forward into new aesthetic territory that reiterated the earlier Dada inquiry into the definition of art. Richard Serra is one of the preeminent American artists and sculptors of the post-Abstract Expressionist period. Beginning in the late 1960s to the present, his work has played a major role in advancing the tradition of modern abstract sculpture in the aftermath of Minimalism. His work draws new, widespread attention to sculpture’s potential for experience by viewers in both physical and visual terms, no less often within a site-specific, if not highly public setting. Andy Warhol was the most successful and highly paid commercial illustrator in New York even before he began to make art destined for galleries. Nevertheless, his screenprinted images of Marilyn Monroe, soup cans, and sensational newspaper stories, quickly became synonymous with Pop art. He emerged from the poverty and obscurity of an Eastern European immigrant family in Pittsburgh, to become a charismatic magnet for bohemian New York, and to ultimately find a place in the circles of High Society. For many his ascent echoes one of Pop art’s ambitions, to bring popular styles and subjects into the exclusive salons of high art. His crowning achievement was the elevation of his own persona to the level of a popular icon, representing a new kind of fame and celebrity for a fine artist.

Works by: Walter De Maria, Lucio Fontana, Donald Judd, Piero Manzoni, Mario Merz, Pablo Picasso, Robert Rauschenberg, Richard Serra, and Andy Warhol.

Photo: Walter De Maria, 14-Sided Open Polygon, 1984, Solid stainless steel with solid stainless-steel ball, 4 x 89 x 89 inches (10.2 x 226.1 x 226.1 cm), © Estate of Walter De Maria, Photo: Rob McKeever, Courtesy Gagosian

Info: Gagosian, 4 rue de Ponthieu, Paris, France, Duration: 2/4-31/5/2025, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 10:30-18:30, https://gagosian.com/