ART CITIES: Paris-Vlassis Caniaris

Vlassis Caniaris produced works that reflected the realities, dreams, situations, and potential viewpoints of economic migrants who moved to western Europe in search of a better life in the 1960s and ’70s. Even before his scholarship in West Berlin from 1973 to 1975, funded by the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), the artist addressed the theme of migration while living in Paris. Caniaris created environments with life-sized dolls that he made himself.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Galerie Peter Kilchmann Archive

The exhibition “Works from 1962 – 1980” features works by Vlassis Caniaris and isthe first major presentation in France since Caniaris’ death. He had a special connection to Paris, where he lived twice with his family from 1960-1966 and from 1969-1976, and where he received in 1970 a solo exhibition at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. Caniaris’ work is a deeply socio-political concern with the human condition within its immediate historical context. Raised in a climate marked by war and occupation in Greece, Caniaris developed an early awareness of power imbalances and injustice, of the discrepancy between appearances and distorted societal aspirations versus the real psychological needs and realities of the people living within that society. The presentation brings together sculptures, assemblages, installations, and works on paper from 1962 to 1980, created during his stays in Paris, Berlin and Athens. It includes significant stages and changes of his work dealing with themes such as the critical examination of the economic miracle, resistance against the aftermath of the military coup in his home country of Greece, and, finally, the problems of migration and the plight of guest workers in Germany. Originally coming from painting, Caniaris first transcended the concept of the figurative ‘window-perspective’, moving into object-based and beyond-the-frame approaches, and ultimately evolving into situational-installative work. A culmination of this development is the large-scale installation “Hélas-Hellas”, which encapsulates everything Caniaris experienced and developed as an artist over twenty years within various socio-political contexts. In 1960, Caniaris moved to Paris (after spending five years in Rome) where he became aware of the Nouveaux Réalistes group. He abandoned traditional canvas painting and began experimenting with everyday materials such as metal mesh, wire, and plaster. Unlike his French colleagues, he did not succumb to the object-euphoria of the new consumer world, but instead exposed the aspect of the dream- and false-world, which failed to live up to its promises of happiness, security and advancement. The sculpture “Just This” by Vlassis Caniaris belongs to the cycle of his “Works on the Economic Miracle”, which he created in Paris from 1961 onwards. It is an assemblage of fabric remnants of various kinds, draped on a spirally bent wire frame and held in shape by glue. The sculpture “Just This” does not represent anything that it is not; it is a concrete sculpture: a demonstration of the ennobling techniques of commodity aesthetics and consumer culture using unsuitable material and a dysfunctional form. The sculpture “Coexistence”, 1964, by Vlassis Caniaris belongs to the cycle of his “Works on the Economic Miracle”, which he created in Paris from 1961 onwards. It consists of a worn shirt wrapped tightly around a small electric heater. The assemblage of these two elements presupposes their dysfunctionality in a practical sense, but evokes exactly what they cannot achieve in this concrete coexistence: Warmth and heat. In 1966, just one year before the military junta abolished Greek democracy, Caniaris returns to Athens. His exhibition, in 1969, at the New Gallery in Athens, which included plaster and barbed wire constructions, caused significant reactions both for its innovative artistic approach and as a demonstration against the dictatorship. The artist, who was also involved in an active group of resistance against dictatorship, was soon forced to leave Athens and returned to Paris. The following year, he showcased the same anti-dictatorship exhibition at the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris. The works of this “Anti-dictatorial” series, featuring every day objects such as shoes, plastic carnations or children’s toys (such as in ‘Untitled’ from 1970), are immersed in plaster and can be seen as metaphors for the state of Greek society ‘cast’ under military dictatorship and waiting to be set free. Between 1973 and 1976, Caniaris moved to Berlin with a DAAD scholarship, where he created the “Gastarbeiter- Fremdarbeiter: series, inspired by the world of immigrant workers coming to Germany, mostly from Turkey, Italy, and Greece. This series includes installations of clothed mannequins wrapped in barbed wire and everyday objects, moving from reflecting humans through real objects to showing humans in a more radical way as objectified. The artwork ‘Garbage Child’ is a powerful piece within this series, critically examining the social and economic dynamics experienced by migrant laborers in industrialized societies, especially during the post-war economic boom in Europe.

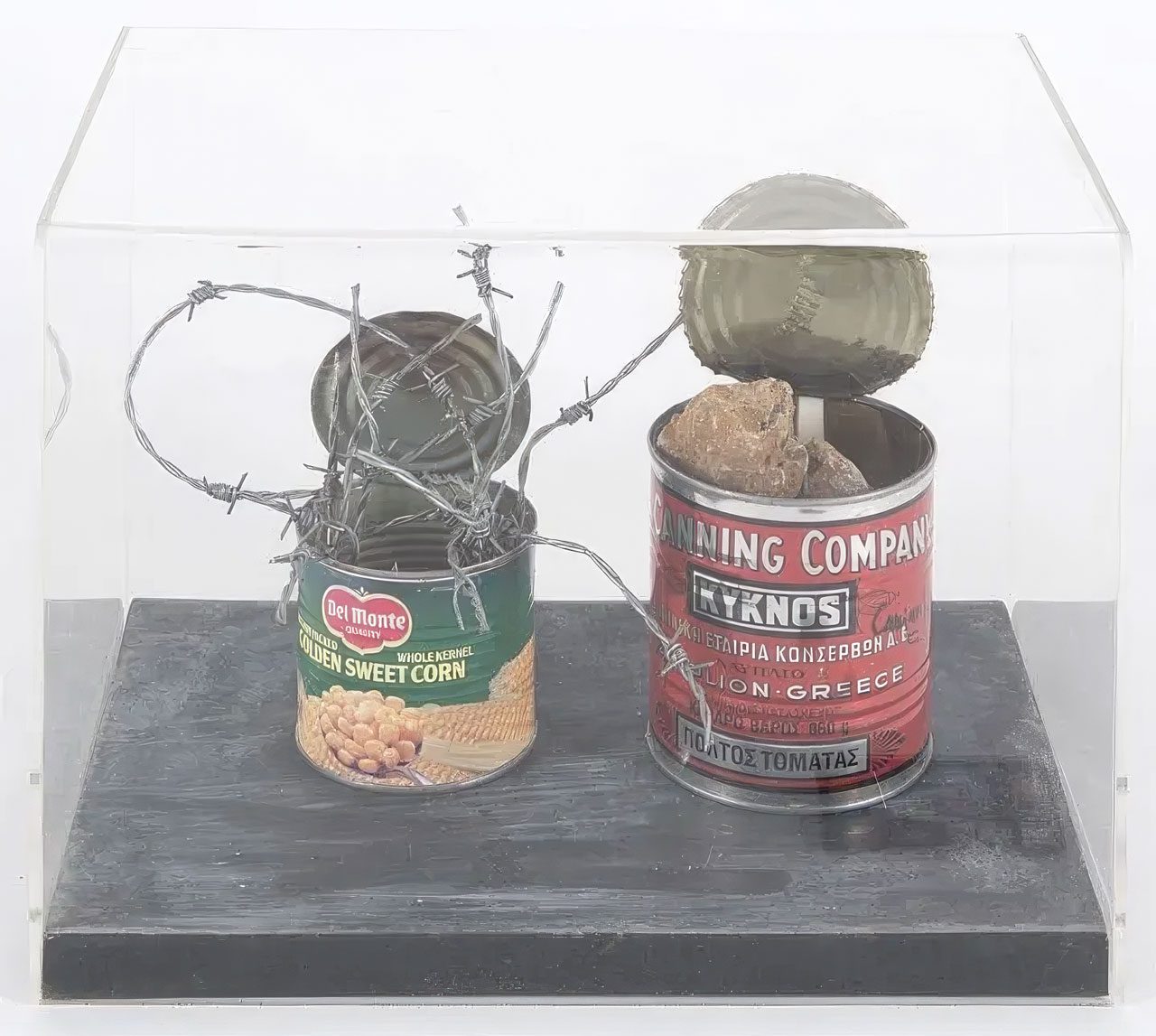

The sculpture, resembling a hybrid between a child’s figure and a wastebasket, uses materials such as wire mesh, plastic, and worn clothing to underscore themes of disposability and marginalization, capturing a sense of displacement and dehumanization. In the room filling installation “Untitled” from 1974 Caniaris puts together parts of a wooden floor, covered with slices of cheap carpet, a children figure only represented with bare woolen stocks, an with objects occupied baby stool and a bargain bin with miscellous items and toys. Although a very bare and poor representation of a home environment, Caniaris brings perfectly to the point the precarious and improvised atmosphere and deprivation of the described space standing for homes of the many. He does not loose himself in drama or additional effects, but proofs an unmistakable exact eye and love in the treatment of the objects, in the selection of positioning, colours, stains and foldings, choosing the less in order to safe more space for a kind of inhabitation of the objects by the ‘soul’ of a whole generation of migrants. He offers us the from reality borrowed items as they are and points out a selection of details, transmitting in the best possible way the essence of the situation. In “Plus und Minus” Caniaris delves into the complexities of migration and the harsh realities faced by migrant workers. In this assemblage, Caniaris uses two tin cans, each symbolizing a different world – the promise of opportunity versus the reality of hardship. One can, labeled with a recognizable American brand, represents the allure of the West, a land often idealized as a place of success and prosperity. However, the barbed wire emerging from the American can serves as a potent symbol of restriction and confinement, evoking the barriers – both literal and figurative – that migrants face. The other can, labeled with a Greek brand, is loaded with simple stones. The juxtaposition of these cans encapsulates the tension between the hope for a better life and the tough circumstances migrants encounter. In 1976, Caniaris was appointed professor and in charge of the art section at the School of Architecture at the National Polytechnic University and returned to Athens. The outstanding installation “Urinals of History” includes a ‘graffitti-wall’ and three human-scale figures from 1980. The clothed scarecrow-like bodies are made from wire mesh and clothes and represent male figures urinating against a painted wall inscribed with red, blue, and green letters reminiscent of political slogans on the walls of Athens during the Nazi occupation, the civil war that followed or later during the military dictatorship. The letters are also reminiscent of Caniaris’ series of paintings ‘Homage to the Walls of Athens’. The installation was first exhibited at Caniaris’ 1980 exhibition “Hélas-Hellas” (Eng: Alas-Greece) in Athens, which marked a breakthrough for the artist. The three men, representing a group of the ‘politically indifferent’ is urinating against a wall, which, although covered and defaced with graffiti and slogans, still stands as a metaphor for the Greeks’ collective effort to erase the memory of their past by disrespecting their heritage. For Caniaris, the wall has special significance as it alludes to the very structure of their existence. Caniaris described his sculptural figures as “witnesses” and locates the visitors on the same representational plane as his subjects: as objects, observers, and participants simultaneously – occupying a radically open position the artist inhabited in his own life and work.

Photo: Vlassis Caniaris, Child’s room, 1974 , Environment made of pasted newspapers and wallpaper, floor lamp, turned over table, curtains, carpet, 3 cups, jam jar, painted plywood boards, metal boar, 150 x 256 x 145 cm (59.1 x 100.8 x 57.1 in.), Courtesy Kalfayan Galleries and Galerie Peter Kilchmann. Photo credit: Kalfayan Galleries

Info: Galerie Peter Kilchmann, 11-13 rue des Arquebusiers, Paris, France, Duration: 21/3-10/5/2025, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 11:00-19:00, www.peterkilchmann.com/