PRESENTATION: Kandinsky’s Universe-Geometric Abstraction in the 20th Century

In the early twentieth century, a profound change occurred in painting: artists no longer sought to represent the visible world, but instead embraced a new, universal pictorial language that reduced artistic expression to the interaction of colors, lines, and forms. In Europe and the United States, this radically modern approach gave rise to multifaceted currents of geometric abstraction that tested the limits of painting, from Suprematism and Constructivism, to the Bauhaus and British postwar abstraction, to Hard Edge painting and Op Art.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Museum Barberini Archive

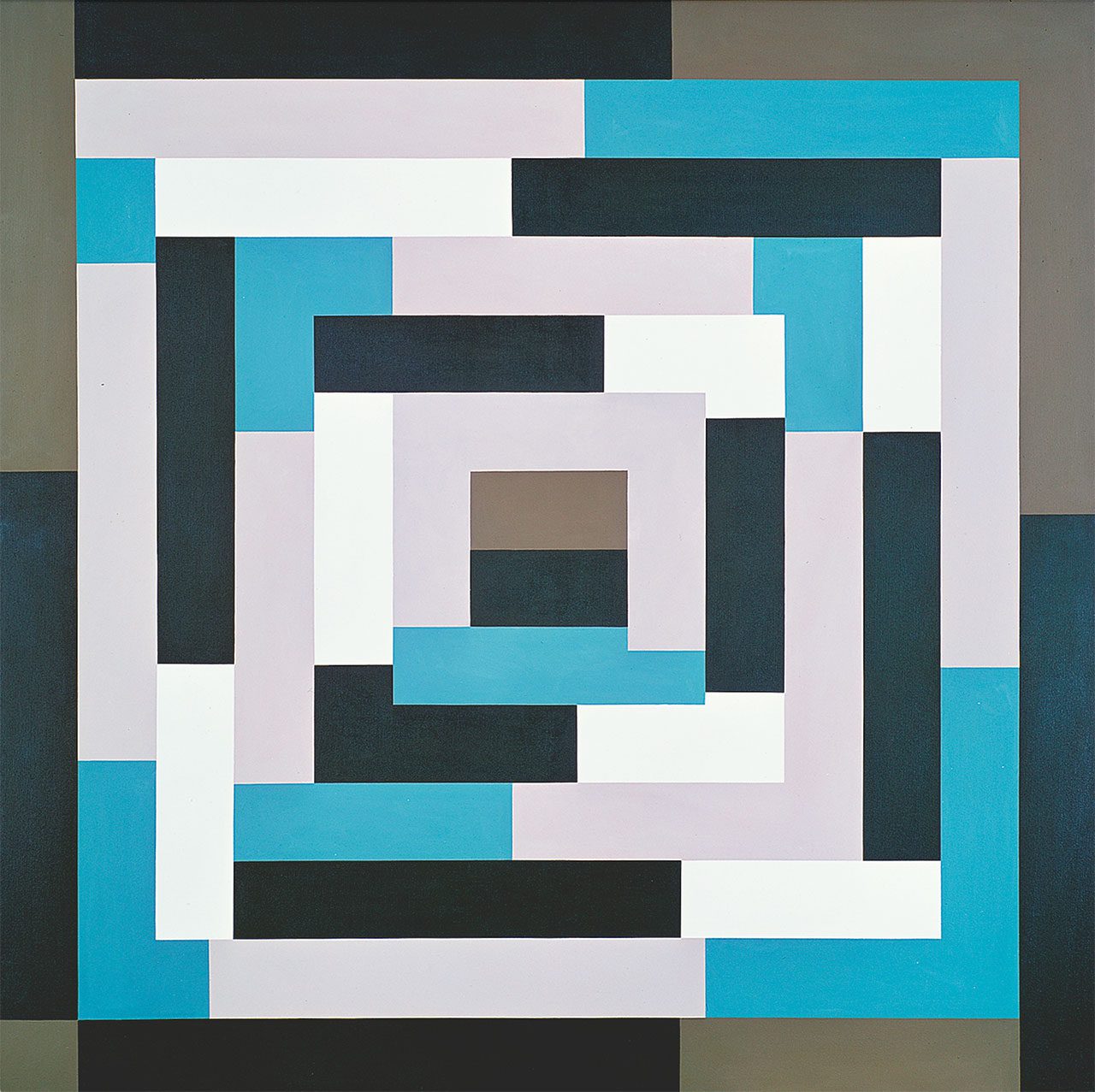

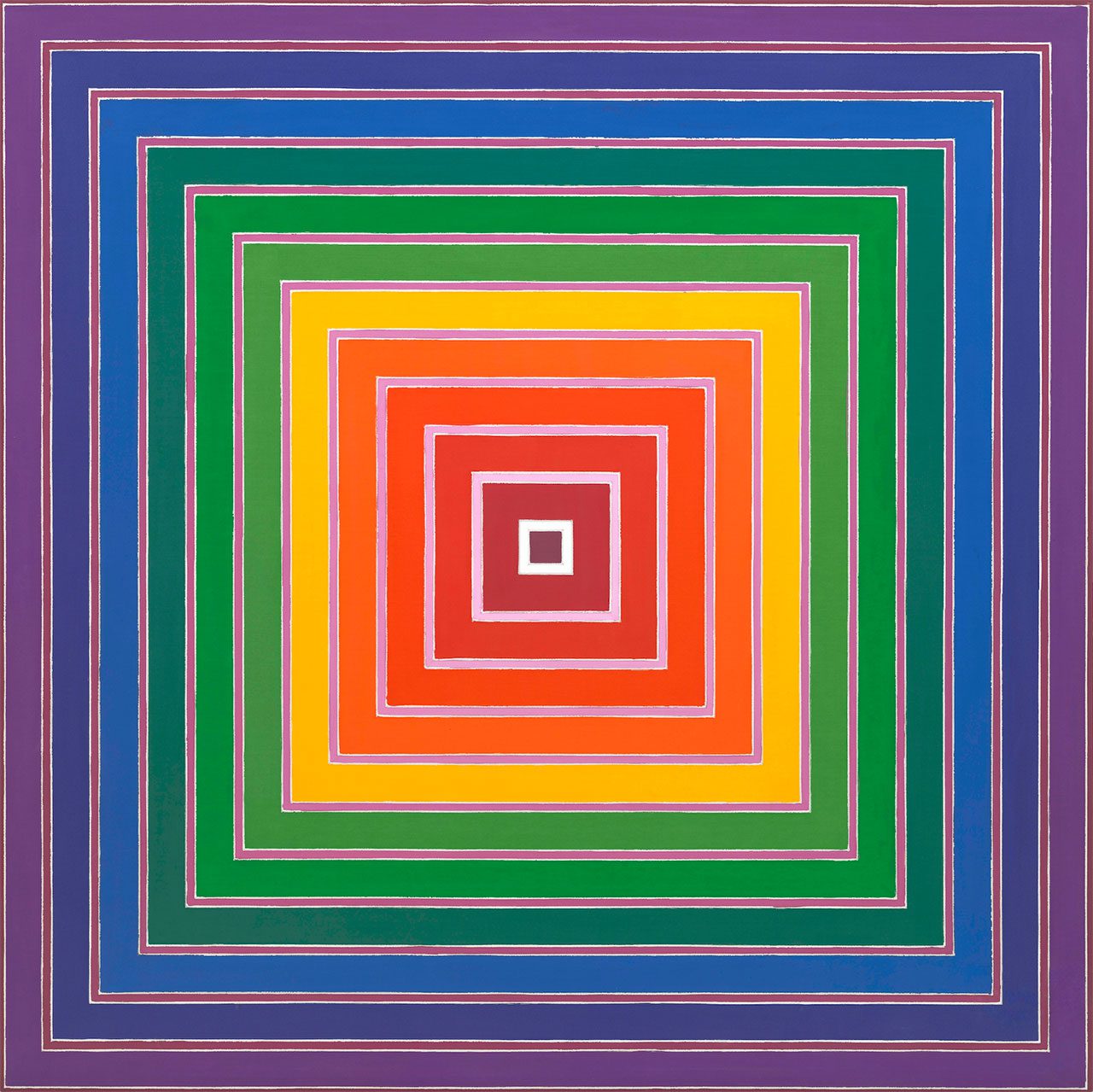

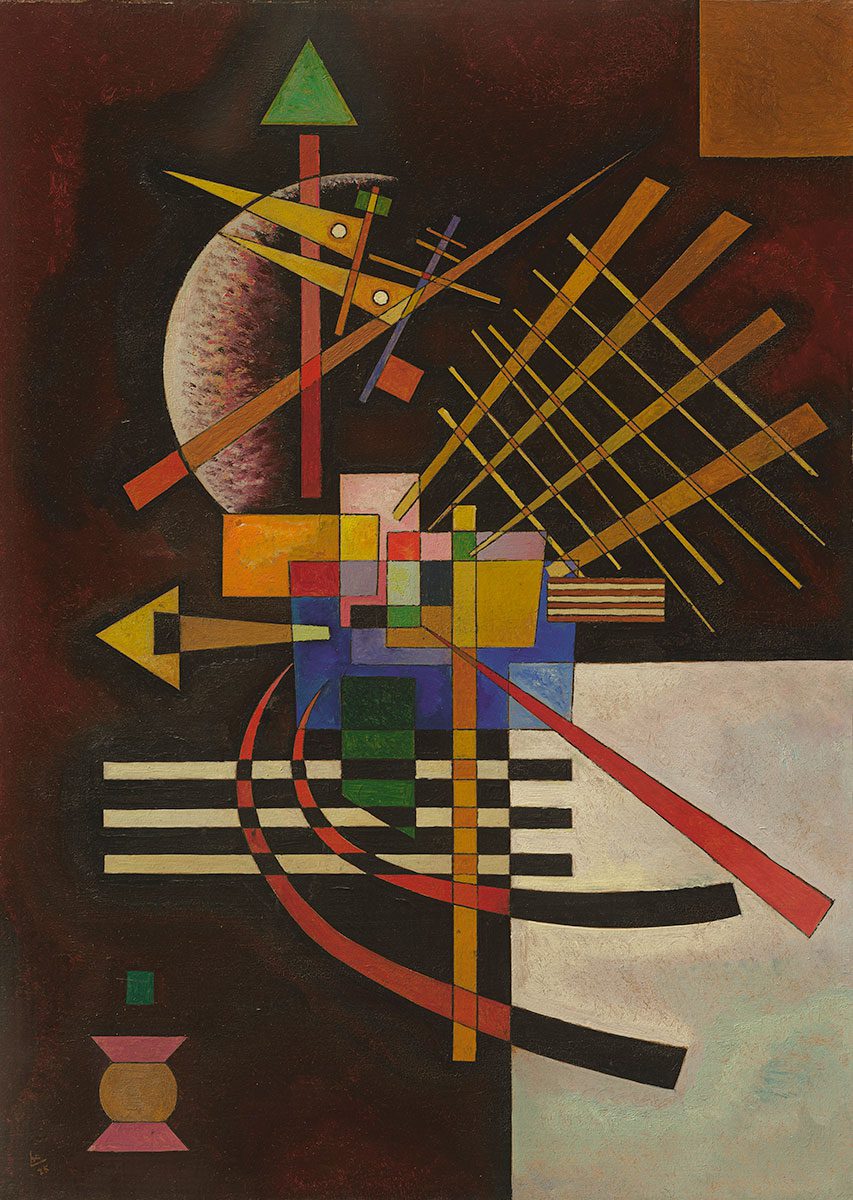

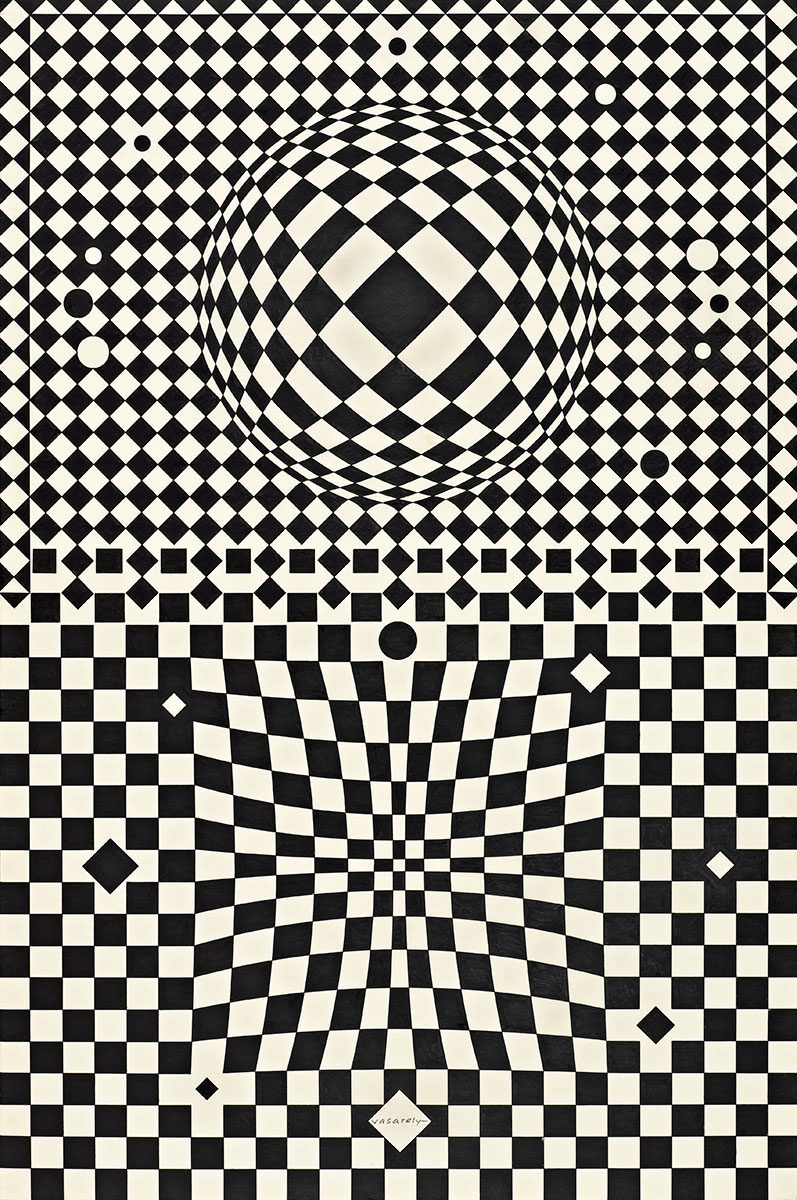

“Kandinsky’s Universe: Geometric Abstraction in the 20th Century” is the first exhibition in Europe to tell the story of geometric abstraction not by presenting a series of national movements, but by tracing the lines of connection between them. A total of 125 paintings, sculptures, and installations by seventy artists show how geometric abstraction challenged the imagination of viewers again and again. Wassily Kandinsky was one of the first painters to explore abstraction. By tracing the stations of his life and the different phases of his abstract oeuvre, the chapters of the exhibition survey the most important stages of geometric abstraction. Beginnings in Munich and Moscow: Wassily Kandinsky was born in Moscow and was initially trained as a legal scholar. In 1896, he began studying art in Munich and from 1908 on showed his first Expressionist works, characterized by bold colors and simplified forms. In the period that followed, he founded the artists’ group Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) and increasingly turned his back on the direct representation of visible reality. In 1911 he published his ground- breaking theoretical work Concerning the Spiritual in Art, which continued to influence the art world into the 1970s. In it, Kandinsky took insights from the neurosciences related to music, dance, physics, and biology and combined them with spiritual ideas such as theosophy, which had strongly informed his oeuvre. His aim was to prove that colors and geometric shapes inherently possessed—and stood in a reciprocal relationship with—universal qualities. After the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Kandinsky was forced to leave Germany. He returned to Moscow, where the first works of Suprematism and Constructivism had already been produced. The artists’ groups to which Kasimir Malevich, Lyubov Popova, Ivan Kliun, and El Lissitzky belonged envisioned a future in which art and technology, spirit and mind were united. Their abstract pictorial language based on lines and geometric planes became the expression of a utopia of progress. In 1917, most artists in Russia devoted their efforts to the service of the revolution and embraced industrial production; Kandinsky, who was more interested in the psychological effect of art on human beings and was persuaded of its “inner necessity,” became an outsider. Beginnings in Munich and Moscow: Wassily Kandinsky was born in Moscow and was initially trained as a legal scholar. In 1896, he began studying art in Munich and from 1908 on showed his first Expressionist works, characterized by bold colors and simplified forms. In the period that followed, he founded the artists’ group Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) and increasingly turned his back on the direct representation of visible reality. In 1911 he published his ground- breaking theoretical work Concerning the Spiritual in Art, which continued to influence the art world into the 1970s. In it, Kandinsky took insights from the neurosciences related to music, dance, physics, and biology and combined them with spiritual ideas such as theosophy, which had strongly informed his oeuvre. His aim was to prove that colors and geometric shapes inherently possessed—and stood in a reciprocal relationship with—universal qualities. After the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Kandinsky was forced to leave Germany. He returned to Moscow, where the first works of Suprematism and Constructivism had already been produced. The artists’ groups to which Kasimir Malevich, Lyubov Popova, Ivan Kliun, and El Lissitzky belonged envisioned a future in which art and technology, spirit and mind were united. Their abstract pictorial language based on lines and geometric planes became the expression of a utopia of progress. In 1917, most artists in Russia devoted their efforts to the service of the revolution and embraced industrial production; Kandinsky, who was more interested in the psychological effect of art on human beings and was persuaded of its “inner necessity,” became an outsider. From the Bauhaus to France: In 1922, Kandinsky was called to the Bauhaus in Weimar, where the artistic influences from Moscow with their interpretation of squares, circles, triangles, and lines left their mark on his work. Surrounded by Bauhaus masters such as Josef Albers, László Moholy- Nagy, and Johannes Itten, his style became more analytical, his forms clearer. In 1926, Kandinsky published “Point and Line to Plane” an analysis of what he viewed as the funda- mental building blocks of art and their emotional effect. Together with his Bauhaus colleagues, Kandinsky also laid the foundation for Concrete Art, a movement that developed during World War II among artists including Max Bill, Verena Loewensberg, and Richard Paul Lohse. Inspired by mathematics and science, their work is marked by bold colors and logically structured patterns, with no reference to nature. When the Bauhaus was closed by the Nazi regime in 1933, Kandinsky once again had to leave Germany. He moved to France, where he became a member of the artists’ group Abstraction-Création, founded in 1931 in Paris. Associated with Piet Mondrian, Alexander Calder, Sophie Tauber-Arp, and Marlow Moss, the artists in this group sought to promote nonobjective art, thereby distancing themselves from the figuration of Surrealism. In this milieu, Kandinsky created works that seem playful, but were often inspired by scientific literature and remained indebted to a geometric formal language. Even apart from the death blow dealt to artistic utopias of progress by the rise of totalitarian systems, Kandinsky continued to view art as a space for exploration of the spiritual. In 1944, Wassily Kandinsky died in Neuilly-sur-Seine near Paris. Connections in Exile: London and New York: World War II marked a caesura in the development of geometric abstraction. With the German occupation of Paris, many artists, art dealers, and critics fled to London before emigrating to the United States. Under the influence of Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson, the British capital developed into a new center of geometric abstraction. After World War II, the group of so-called Constructionists was established in London, inspired by the Constructivists of the prewar years. They employed newly developed synthetic materials such as plastic, acrylic, and fiberglass in combination with wood and aluminum. Works by Mary Martin, Victor Pasmore, and Kenneth Martin reflect the optimistic wave of modernization that shaped postwar reconstruction. In the United States as well, the ideas of European exiles continued to influence the evolution of geometric abstraction in the work of American artists. In the 1960s, Frank Stella, Ellsworth Kelly, and Carmen Herrera initiated the movement known as Hard Edge painting. Characterized by clear forms, sharp contours, and brilliant colors, it distanced itself from the expressive approach that had dominated the New York art scene in the 1950s. A concurrent and contrasting movement emerged with Minimalism, with works by Donald Judd, Jo Baer, and Agnes Martin that embraced radical simplicity. The artists of Op Art played with the limits of visual perception. Echoing Wassily Kandinsky and Kasimir Malevich, who had experimented with floating pictorial elements, Bridget Riley, Victor Vasarely, Richard Anuszkiewicz, and Julian Stanczak introduced optical movement into static paintings. This movement linked the discoveries of the Bauhaus on the effects of colors and forms with the fascination for technology, space travel, and the visual experience of television characteristic of the 1960s.

Spirit and Technology, Geometric Art in Russia and Eastern Europe: After the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Kandinsky returned from Munich to Moscow, where the first Constructivist artworks had already emerged. The artists utilized lines and geometric planes to create a universal visual language that expressed modernity and progress. After 1917, the new state briefly supported avantgarde art forms to promote revolutionary ideals. Kandinsky played a key role in this effort. As the founding director of a state research institute, he investigated the psychological effects of art. While the Constructivists dedicated their work to industrial production, Kandinsky’s insis- tence on the spiritual dimension of art made him an outsider. In 1922, he returned to Germany. His subsequent works reflect the influence of the geometric visual language developed by his colleagues in Moscow. Straight Lines, Right Angles-The Abstract Rhythms of the De Stijl Group: In the Netherlands, Piet Mondrian, Theo van Doesburg, and others founded the De Stijl group in 1917. Inspired by spiritual ideas, jazz music, and urban life, they sought to give visual form to rhythms and energies. Their art was characterized by straight lines, right angles, and a palette of primary colors, black, and white. They aimed to express balance and harmony, creating a model for social and architectural transformation. From its inception, De Stijl had an international outlook; its founding manifesto was published in four languages. Van Doesburg maintained close ties with the Bauhaus and avant-garde artists across Europe. Mondrian’s move to Paris and later his exile in London and New York further disseminated the movement’s ideas. Even after the dissolution of De Stijl in 1931, younger artists continued to adopt its principles, further developing them with the use of diagonals, curves, and relief elements. Universal Language of Abstraction-Bauhaus and Concrete Artists: As a teacher at the Bauhaus, founded in Weimar in 1919, Kandinsky continued to develop his theories alongside other avant-garde artists. He developed a geometric visual language. In his 1926 book “Point and Line to Plane”, he explored the fundamental elements of art and their emotional resonance. The Bauhaus curriculum was shaped by a focus on color and form. The emphasis on geometric shapes influenced not only painting but also design and industrial production. Simplicity, functionality, and mass production were regarded as the cornerstones of a modern, democratic society. During World War II, Max Bill, a former Bauhaus student, initiated the Concrete Art movement in Zurich. This style is characterized by bold colors and logically structured compositions. The term “concrete” underscores, even more strongly than “abstract,” that these works have no connection to the visible world. Flowing Forms-International Abstraction in Paris: After the forced closure of the Bauhaus by the Nazi regime in 1933, Kandinsky emigrated to France. There, he joined the group Abstraction-Création, an international forum for abstract art. Many artists fled to Paris to escape political persecution. Under the influence of the Surrealists, Kandinsky began incorporating biomorphic forms into his works. The dominance of the Surrealists, who focused on the unconscious, led to a shift among many members of Abstraction-Création: rigid grid structures gave way to playful compositions and organic shapes. Kandinsky remained in France until his death in 1944. Despite the turmoil of World War II, he continued to explore the spiritual through his art. Many of his colleagues who fled Europe never returned to Paris. In 1946, the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles was founded to promote abstract art and revitalize the Parisian art scene. Balanced Forces-Constructivist Utopias in British Art: In the late 1930s, as the threat of war loomed, many artists fled to Great Britain. London became a center for geometric abstraction, with exiled artists such as Mondrian, Moholy- Nagy, and Gabo finding refuge there before emigrating to the United States. Connections to British artists like Hepworth and Nicholson had already been established through the Paris-based group Abstraction-Création. Even before the bombing of London in 1940, Hepworth and Nicholson moved to the artist colony in St. Ives, Cornwall. There, they continued their work on reliefs and sculptures, adapting geometric abstraction into three-dimensional forms. They were inspired by the colors and shapes of the coastal landscape. After the war, the Constructionists group formed in London. Their reliefs, which resemble industrial objects of the 1950s, incorporated new synthetic materials. These works reflected the optimism and modernization of postwar reconstruction. The Power of Color-Hard Edge Painting: In the 1960s, geometric abstraction in the United States turned to monumental formats. Artists focused on basic shapes, sharp contours, and vibrant colors, moving away from the expressive painting that had dominated the American art scene in the 1950s. In Washington, a group around Kenneth Noland developed special techniques: they poured or dragged diluted paints over large areas of the canvas, experimenting with the psychological effects of colors and their combinations. New York artists like Al Held and Frank Stella avoided expressive brushwork. In their style, known as Hard Edge, color and form refer only to themselves. They reflected the geometric abstraction of the prewar era but without pursuing utopian ideas. Despite the rejection of narrative elements, often titles, compositions, and color contrasts hint at cultural or personal contexts. The Essence of Form-Transatlantic Minimalism: Clear lines, industrial materials, and a reduced color palette define Minimalism. In his 1964 text “Specific Objects,” Donald Judd articulated the characteristics of this new style. Throughout the 1970s, numerous artists in the United States and Europe embraced Minimalism. Rather than focusing on emotion or symbolism, Minimalist works invite viewers to perceive subtle nuances: the interplay of light and shadow on a surface, the texture of materials, or the shifting relationship between object and space as the observer moves. Minimalism distanced itself from the notion of the artwork’s uniqueness and concealed traces of manual craftsmanship. Some artists even opted for industrial production of their works. Canvases were treated not as image carriers but as objects—nails form three-dimensional structures, grids overlap, and edges are painted. Space Age-Op Art in the Sixties: Op Art challenges visual perception. Patterns on a two-dimensional surface appear to move or protrude, creating an illusion that turns seeing into an active experience. As early as the 1910s and 1920s, artists like Malevich and Kandinsky had experimented with geometric elements that seem to float or appear dynamic. Op Art built on this foundation. It drew on the insights of color and form effects developed at the Bauhaus, translating them for the 1960s aesthetic, which was shaped by technology, space exploration, and the flicker of television screens. Art that played with optical effects emerged independently in various places. It was only recognized as a distinct style in 1965 with the exhibition The Responsive Eye at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Luminous Illusions-The Effect of the Square: The American Op Artists Richard Anuszkiewicz and Julian Stanczak were students of the former Bauhaus teacher Josef Albers. Albers had emigrated to the United States in 1933, where he began his series Homage to the Square. These geometric compositions continued the research on color and form, which he had begun at the Bauhaus alongside Kandinsky—they are considered precursors to Op Art. Both students adopted Albers’ square framework. Like him, they explored how colors can seem opaque or transparent, and appear to advance or recede depending on their combination. However, they introduced brighter colors and stronger contrasts, creating intense effects that push the boundaries of perception.

Works by: Josef Albers, Edna Andrade, Richard Anuszkiewicz, Jo Baer, Max Bill, Alexander Calder, Enrico Castellani, Ilya Chashnik, Gene Davis, Jo Delahaut, Sonia Delaunay, Walter Dexel, Burgoyne Diller, Theo van Doesburg, César Domela, Boris Ender, John Ernest, Alexandra Exter, Wojciech Fangor, Terry Frost, Naum Gabo, Fritz Glarner, Jean Gorin, Camille Graeser, Al Held, Jean Hélion, Barbara Hepworth, Auguste Herbin, Carmen Herrera, Anthony Hill, Paul Huxley, Johannes Itten, Donald Judd, Wassily Kandinsky, Ellsworth Kelly, Ivan Kliun, Katarzyna Kobro, Jean Leppien, Alexander Liberman, El Lissitzky, Verena Loewensberg, Richard Paul Lohse, Kasimir Malevich, Agnes Martin, Kenneth Martin, Mary Martin, László Moholy-Nagy, Piet Mondrian, François Morellet, Marlow Moss, Aurélie Nemours, Ben Nicholson, Kenneth Noland, Victor Pasmore, Antoine Pevsner, Lyubov Popova, Paul Reed, Bridget Riley, Alexander Rodchenko, Miriam Schapiro, Julian Stanczak, Frank Stella, Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Victor Vasarely, Mary Webb, Margaret Wenstrup

Photo: Exhibition view “Kandinsky’s Universe: Geometric Abstraction in the 20th Century”, Museum Barberini-Podsdam 2025, Photo: © David von Becker, Courtesy Museum Barberini

Info: Curator: Sterre Barentsen, Museum Barberini, Alter Markt, Humboldtstraße 5– 6, Potsdam, Germany, Duration: 15/2-18/5/2025, Days & Hours: Mon & Wed-Sun 10:00-19:00, www.museum-barberini.de/