ARCHITECTURE: Crossed Histories

Born in the 1920s, critic Ada Louise Huxtable and architects Gae Aulenti and Phyllis Lambert were among the most influential figures in architecture and design during the postwar boom. Pioneers in what was then a largely male-dominated field, and key players in the transition from modernism to postmodernism, they set out to conquer the public spaces they designed and built.

By Efi Michalarou

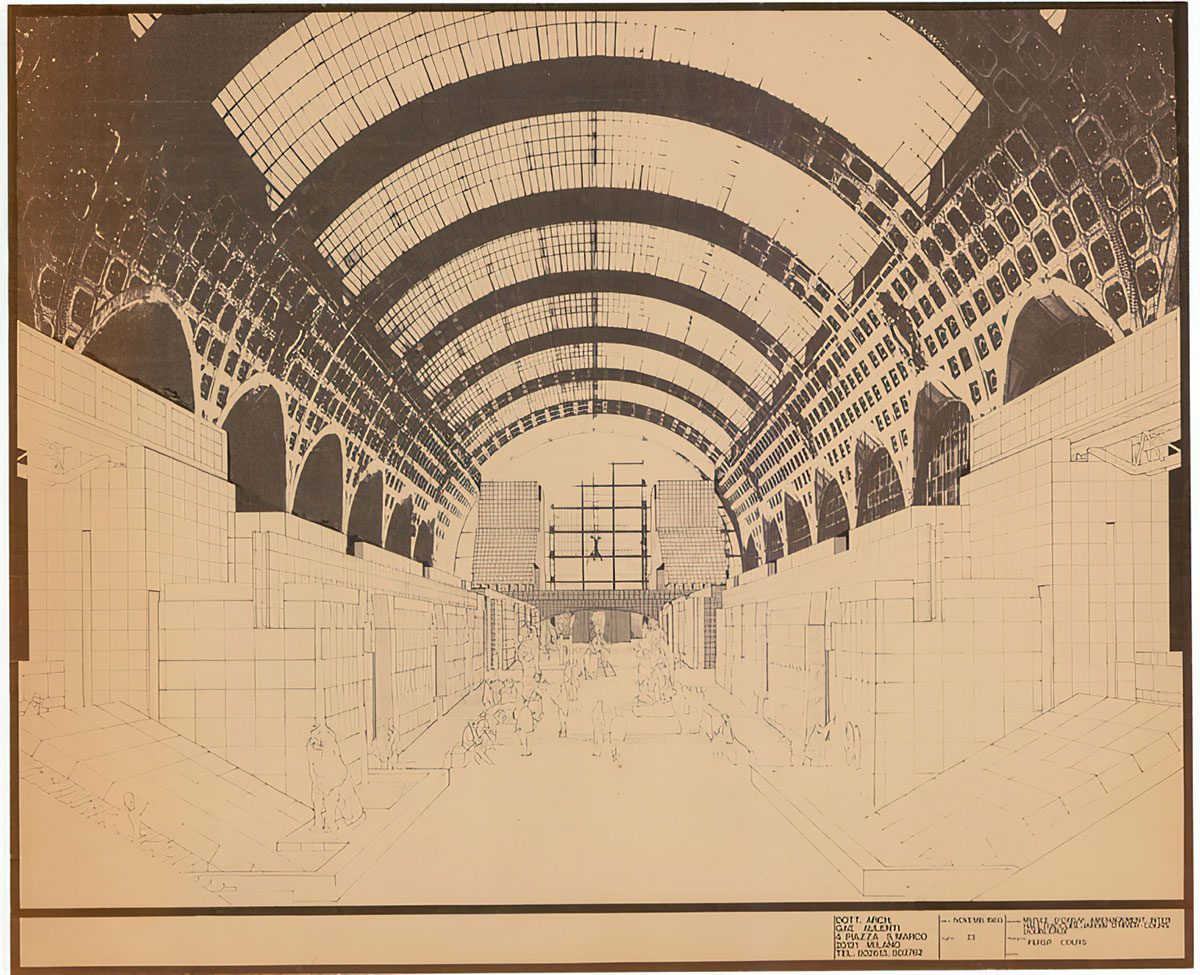

Photo: Canadian Cultural Centre Archive

Through accounts, archival images, drawings and photographs, the exhibition “Crossed Histories (Gae Aulenti, Ada Louise Huxtable, Phyllis Lambert, on Architecture and the City” sheds light on some of their emblematic achievements and interweaves their extraordinary biographies to rethink the crucial role of women in the history of 20th-century architecture. The three protagonists of this exhibition have taken the debate on architecture and the city to the public space and the metropolis. They have succeeded in preserving entire districts of their beloved cities, or in changing the general public’s view of what they can contribute to their environment. How did they do it? Thanks to or despite what circumstances? While many recent studies have focused on single narratives and individual stories, “Crossed Histories” proposes to explore five projects from the second half of the last century: The Seagram Building and its Plaza (New York), The Destruction of Pennsylvania Station, The project to document Montreal’s grey stone buildings and the creation of the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA), the Musée d’Orsay (Paris) and Piazzale Cadorna (Milan), and thus follows a series of thematic red threads that interweave these stories into a tightly woven network of relationships that, together, will establish a new collective narrative. The result of the exhibition is an unprecedented collection of images and documents thematically linking Canada, United States, France and Italy. It also includes exclusive interviews, conducted in 2024, with Phyllis Lambert (architect and founder of the Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal), Alexandra Lange (architecture and design critic, New York), Mary McLeod (professor of architecture, Columbia University, New York), Mirko Zardini (curator and architecture critic, Milan, former director of the Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal), Giovanna Borasi (director of the Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal), Maristella Casciato (curator of architecture, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles), and Barry Bergdoll (professor of art history and archaeology, Columbia University, New York).

Gae Aulenti (4/12/1927-21/10/20120) was an Italian architect and designer known for her bold and innovative approach to architecture, interior design, and industrial design. She was one of the few prominent female architects of her time, earning international acclaim for her ability to blend modernist principles with historical and cultural contexts. Born in Palazzolo dello Stella, a small town in northeastern Italy, Aulenti pursued architecture at the Polytechnic University of Milan, graduating in 1953. Her education coincided with the post-war reconstruction period, an era marked by intense debates over modernism and traditionalism in architecture. She was influenced by the Italian movement *Neoliberty*, which sought to move beyond the rigid rationalism of modernism by incorporating historical references and decorative elements. Aulenti’s career spanned over six decades, during which she worked on a variety of projects ranging from museum renovations and urban planning to furniture and lighting design. She initially gained recognition as an editor and contributor to “Casabella”, an influential architectural magazine that promoted innovative design ideas. Her work was characterized by a commitment to contextual design, respecting the history and identity of a place while introducing modern elements. Unlike many of her modernist contemporaries who favored stark minimalism, Aulenti believed in creating spaces with depth, texture, and cultural continuity. One of Aulenti’s most renowned projects was the transformation of the Gare d’Orsay railway station in Paris into the Musée d’Orsay (1980–1986). She skillfully adapted the grand 19th-century Beaux-Arts station into a modern museum while preserving its historical essence. The project became a landmark in adaptive reuse and solidified her reputation as a master of museum design. Other significant projects include: Palazzo Grassi (1985–1986), Asian Art Museum (2003), San Francisco. Beyond architecture, Aulenti designed furniture, lighting, and interiors, working with prestigious brands like FontanaArte and Artemide. Her “Pipistrello” lamp (1965) remains an iconic piece of modern design. Gae Aulenti broke barriers in a male-dominated field, proving that women could lead major architectural projects on the global stage. She received numerous awards, including the prestigious Praemium Imperiale for Architecture in 1991. Her legacy is one of innovation, cultural sensitivity, and bold reinterpretation of historical spaces. Through her designs, Aulenti demonstrated that architecture could honor the past while embracing the future.

Ada Louise Huxtable (14/3/1921-7/1/2012) was an American architecture critic and writer, widely regarded as one of the most influential voices in architectural journalism. A champion of thoughtful urban design and historic preservation, she was the first-ever architecture critic to win the Pulitzer Prize. Her sharp critiques, insightful analyses, and passionate advocacy helped shape public discourse on architecture and urban planning for over half a century. Born Ada Louise Landman in New York City, Huxtable developed an early appreciation for architecture, influenced by her father, an industrial designer. She attended Hunter College, where she graduated in 1941, and later pursued graduate studies in architectural history at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts. Huxtable began her career at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in the 1940s, working as an assistant curator of architecture and design. She then transitioned to writing, contributing essays and critiques to publications such as “Progressive Architecture” and “The New York Times. In 1963, she became “The New York Times” first full-time architecture critic, a groundbreaking role in journalism. Her writing was known for its wit, accessibility, and deep understanding of both architectural aesthetics and their social impact. She was unafraid to criticize bland modernist buildings or reckless urban development while advocating for designs that balanced innovation with historical and human-scale considerations. Some of her most notable contributions include: Championing the preservation of New York landmarks, such as Grand Central Terminal and the historic cast-iron buildings of SoHo. Criticizing the destruction of historic architecture in favor of uninspired commercial developments. Promoting public awareness of how architecture shapes urban life, making her writing influential beyond just the architectural community. In 1970, Huxtable won the “Pulitzer Prize for Criticism”, becoming the first recipient in that category. She later joined “The Wall Street Journal” as an architecture critic in 1997, continuing her sharp, insightful commentary well into her 80s. Her work laid the foundation for contemporary architectural criticism, influencing generations of writers and architects. She was awarded the National Medal of Arts in 1996, recognizing her contributions to architectural discourse. Huxtable’s voice was a powerful force in shaping the modern cityscape, advocating for intelligent design and responsible preservation. She passed away on 7/1/2013, but her legacy endures through her writings and the many preserved buildings she fought to protect. Ada Louise Huxtable remains a towering figure in architecture criticism—an eloquent, fearless advocate for cities that respect both history and progress.

Phyllis Lambert (24/2/1927- ) is a Canadian architect, preservationist, and philanthropist whose work has redefined urban landscapes and architectural discourse. Born into the influential Bronfman family—her father, Samuel Bronfman, founded the Seagram Company—Lambert leveraged her privilege to champion modernist architecture and heritage conservation, earning her the moniker “Joan of Architecture”. Educated at Vassar College (BA, 1948), Lambert’s architectural journey began in 1954 when she intervened in her father’s plans for the Seagram Building in New York. Dissatisfied with the initial design, she persuaded him to hire Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, whose minimalist vision resulted in the iconic Park Avenue skyscraper. Lambert served as the project’s director of planning (1954–1958), cementing her role as a bridge between corporate ambition and architectural integrity. Inspired by Mies, she pursued a master’s degree in architecture at the Illinois Institute of Technology (1963). Her design portfolio includes Montreal’s Saidye Bronfman Centre (1960s), a Miesian-inspired cultural hub named after her mother, and the restoration of Los Angeles’ Biltmore Hotel, which earned a National Honor Award from the American Institute of Architects. Lambert’s passion for preservation ignited after the 1973 demolition of Montreal’s Van Horne Mansion, a catalyst for her co-founding Heritage Montreal (1975) to protect the city’s architectural heritage. She spearheaded Canada’s largest cooperative housing project, Milton-Parc, and saved the 19th-century Shaughnessy House, later integrating it into the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA), which she founded in 1979. The CCA, a global hub for architectural research, reflects her belief that architecture is a “public concern”. Her accolades include the Order of Canada (Companion, 2001), the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the Venice Biennale (2014), and the Wolf Prize in Arts (2016). Lambert’s advocacy extends beyond buildings; she emphasized community-driven urban planning, arguing that cities must balance modernization with historical continuity. A polymath—architect, curator, photographer, and activist—Lambert reshaped architectural practice by intertwining preservation with innovation. Her work at the CCA and her writings, such as Mies in America (2001), underscore her commitment to architectural education and critical discourse. As Rem Koolhaas noted, she “made architects,” fostering a global dialogue on design’s societal role.

Photo: Phyllis Lambert, Espace en négatif, New York City/Negative space, New York City, 1968 (tirage chromogénique/chromogenic print), Collection Phyllis Lambert, Montréal/Phyllis Lambert Collection, Montreal, PL-1596. © Phyllis Lambert.=

Info: Curator: Léa-Catherine Szacka, Associate curator: Catherine Bédar, Canadian Cultural Centre, 130 rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, Paris, France, Duration: 13/2-17/5/2025, Days & Hours: Mon-Fri 10:00-18:00, https://canada-culture.org/