ART CITIES: Vienna-Liliane Lijn

Liliane Lijn has been working at the intersection of visual art, poetry and science for over six decades. Her category-defying work takes its starting point in the late 1950s, in the context of kinetic art, and in experiments with light, energy and movement. These early works demonstrate the artist’s ongoing interest in innovative materials and technologies, as well as the latest scientific findings. In the 1980s, Lijn created multimedia sculptures in which she explored the human body and alternative conceptions of the feminine. Combining the cosmic with the personal and mythology with high-tech, these interactive works give a contemporary form to female archetypes.

Liliane Lijn has been working at the intersection of visual art, poetry and science for over six decades. Her category-defying work takes its starting point in the late 1950s, in the context of kinetic art, and in experiments with light, energy and movement. These early works demonstrate the artist’s ongoing interest in innovative materials and technologies, as well as the latest scientific findings. In the 1980s, Lijn created multimedia sculptures in which she explored the human body and alternative conceptions of the feminine. Combining the cosmic with the personal and mythology with high-tech, these interactive works give a contemporary form to female archetypes.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: mumok Archive

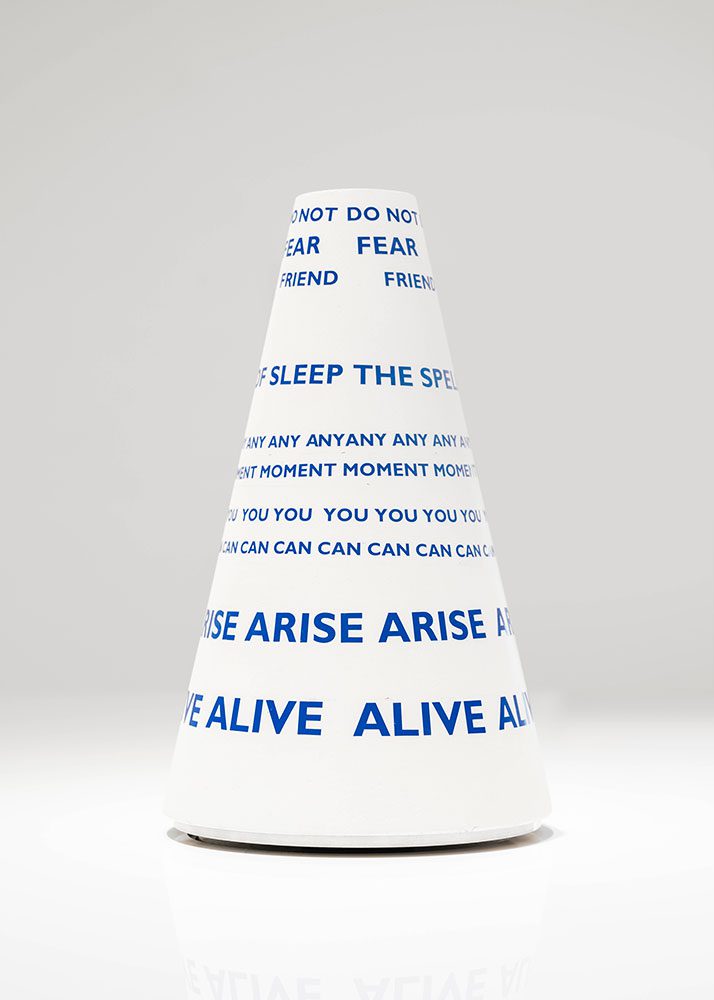

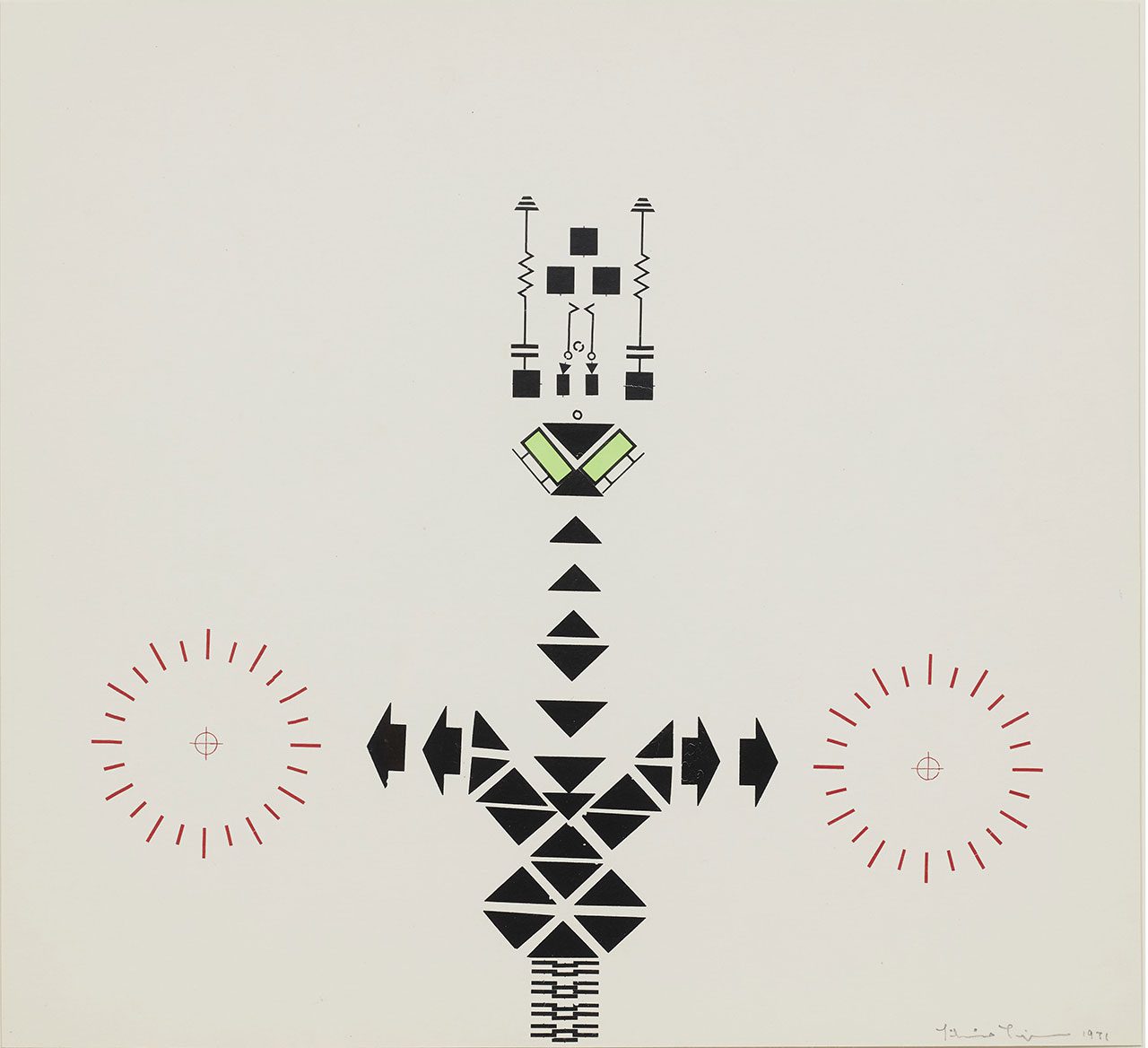

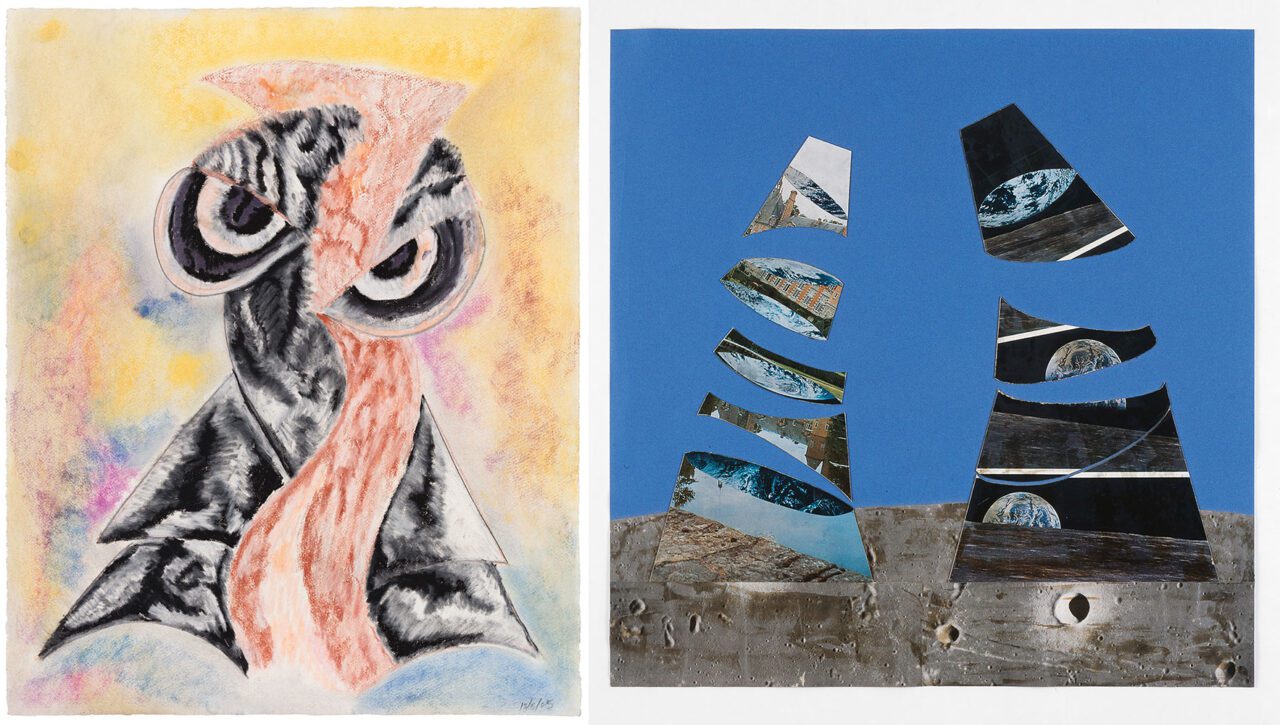

“Arise Alive” is Liliane Lijn’a most comprehensive institutional solo presentation to date. The exhibition brings together a selection of artworks produced by Liliane Lijn over a period of six decades. From her early drawings to kinetic pieces and artworks that engage with language and poetry, the display traces a trajectory that extends all the way to her decidedly feminist works—first produced in the late seventies before becoming more prominent in the eighties—in which she sought new forms of the feminine. In her works, which are often organized into groups and series, Lijn addresses themes such as dreams and the unconscious, experiments with light, energy, and movement, and embarks on a search for origins and personal beginnings. In so doing, she continually undercuts simplistic, dualistic thinking, oscillating between heaven and earth, body and mind, science and spirituality. Lijn’s artistic career began with drawing. One of her first works, from 1959, is titled “Two Worlds”. In it, a stark, rigid triangle creates an empty center of negative space, enclosed by a mass of entwined bodies; it is a wild and chaotic scene, a kind of primordial soup. Lijn herself associates the triangle with the mind, and the void at the center with clarity of thought, while in her imagination, the circle represents a powerful corporeality and an ever-ambivalent emotional world. Lijn’s marked interest in dual structures, which would go on to characterize her work in various guises, is already clearly articulated here. In the same year, she created “The Beginning” a graphic artwork that is similar to Two Worlds in terms of its formal aspects—, which depicts on a round piece of paper a maelstrom of clouds and mountain-like formations encircling a dense, flaming center—in Lijn’s own words, products of an “unconscious whirling around and separating out from a fiery and as yet condensed central core.” This drawing constitutes the energy source of her entire artistic practice; it is the “primordial work” at the genesis of her oeuvre. It anticipates Lijn’s engagement with energy and dynamics, as well as her search for mythological origins and her striving to depict them. The “Sky Scrolls”, on the other hand, which were produced in 1959/60, provide an early example of Lijn’s interest in Eastern philosophy and astronomical constellations and cosmologies. These works draw on ancient Chinese precursors, which Lijn had studied at the Musée Cernuschi in Paris. These landscape-format watercolors, which are intersected by lateral stripes, each shows a skyscape featuring fantastical, enchanted details, which upon closer inspection reveal themselves to be mythical creatures emerging from the cloudy plumes of color. As in The Beginning, in this work, too, Lijn shows the viewer a dynamic world caught in a perpetual process of becoming. Created in 1962, “Vibrographe” ushered in a new phase in Liliane Lijn’s artistic career. Two metal drums covered with Letraset lines rotate, powered by a motor, with the move- ment giving rise to patterns of interference. Here, movement is no longer depicted, as it is in “The Beginning”, for example, but is instead rendered a constructive element of the work. The inspiration source for this early, motorized work was an exhibit at the Palais de la Découverte, a science museum in Paris, which fascinated Lijn during one of her visits. In her” Poem Machines”, Lijn took this principle even further. She realized that the letters of the alphabet are also comprised of lines, and that whole words can be translated into oscillations. To this end, she extracted single units of meaning from poems penned by her poet friends. In these works, Lijn literally divorces language from its context and juxtaposes the supposed subjectivity of poetry with the stoic, mechanical movement of the machine. She accelerates the words, hurls them into the space, and “frees” them—not just from their original context, but also from their fixed meanings. As they rotate, the words disintegrate, becoming energetic oscillations—of another, living form of poetry. Lijn’s work with Letraset symbols also inspired her to create two series of works on paper: “Electronic Symbols” (1966–70) and “Neurographs” (1971). In these graphic compositions, it is not primarily letters that form the foundation of the works, but the signs typically used in electrical blueprints to designate wires, voltage, and resistance; as such, the works navigate questions of communication and exchange and how information is interpreted. In 1965, in close relation to the “Poem Machines”, Lijn began a series that would go on to play a pivotal role in her oeuvre and to which she continues to add to this day: her “Koans” series. Instead of cylinders, for these sculptures she uses cones that spin around on top of motorized platforms. The surfaces of the cones bear letters, words, or mathematical formulae, and in some cases also simple, concentric lines. In reality, these lines consist of sheets of fluorescent Plexiglas, which divide the cones into uneven elliptical sections. Illuminated from within, they appear to the viewer as lines, which move rhythmically along the length of the spinning sculpture, calling to mind the orbital paths of celestial bodies.

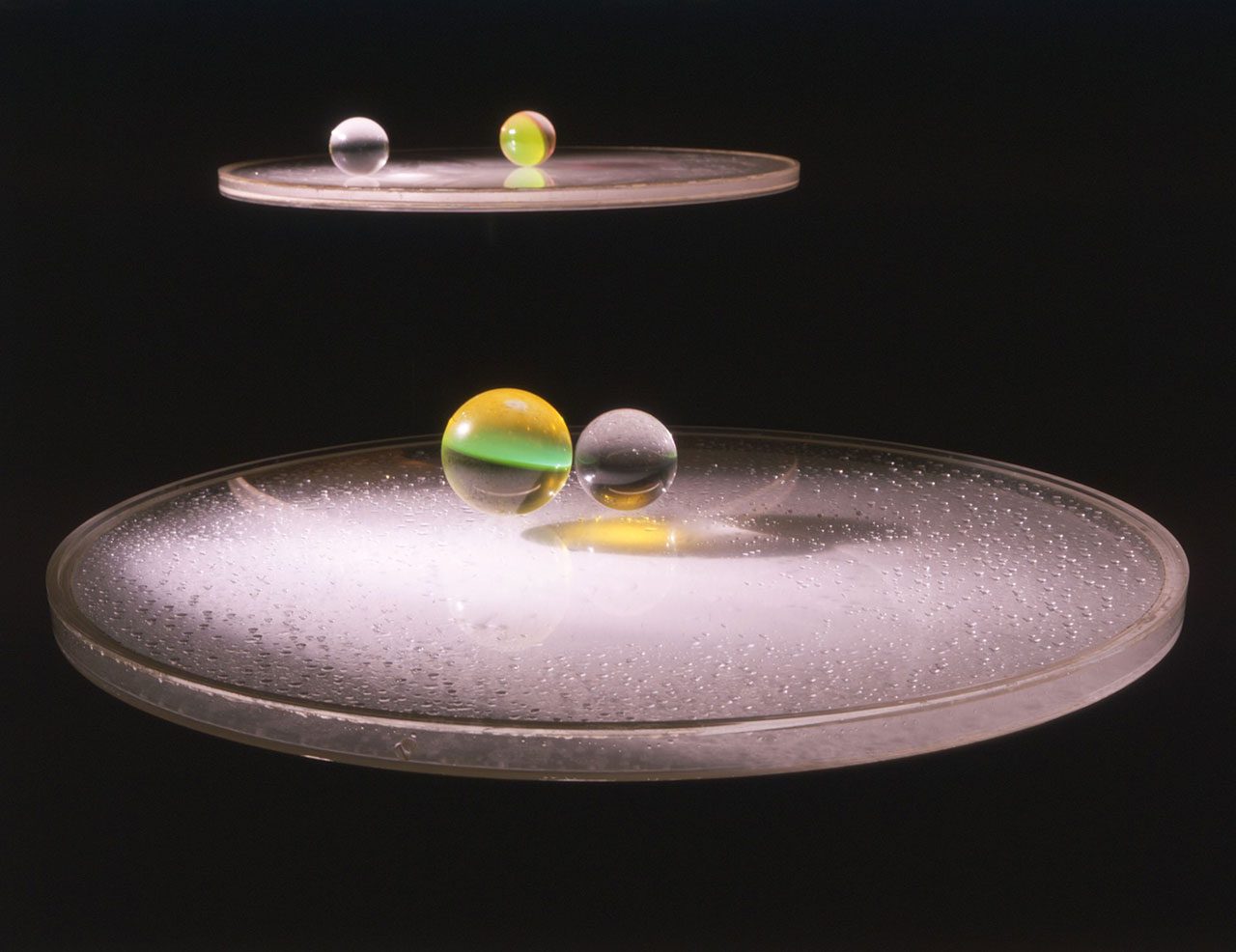

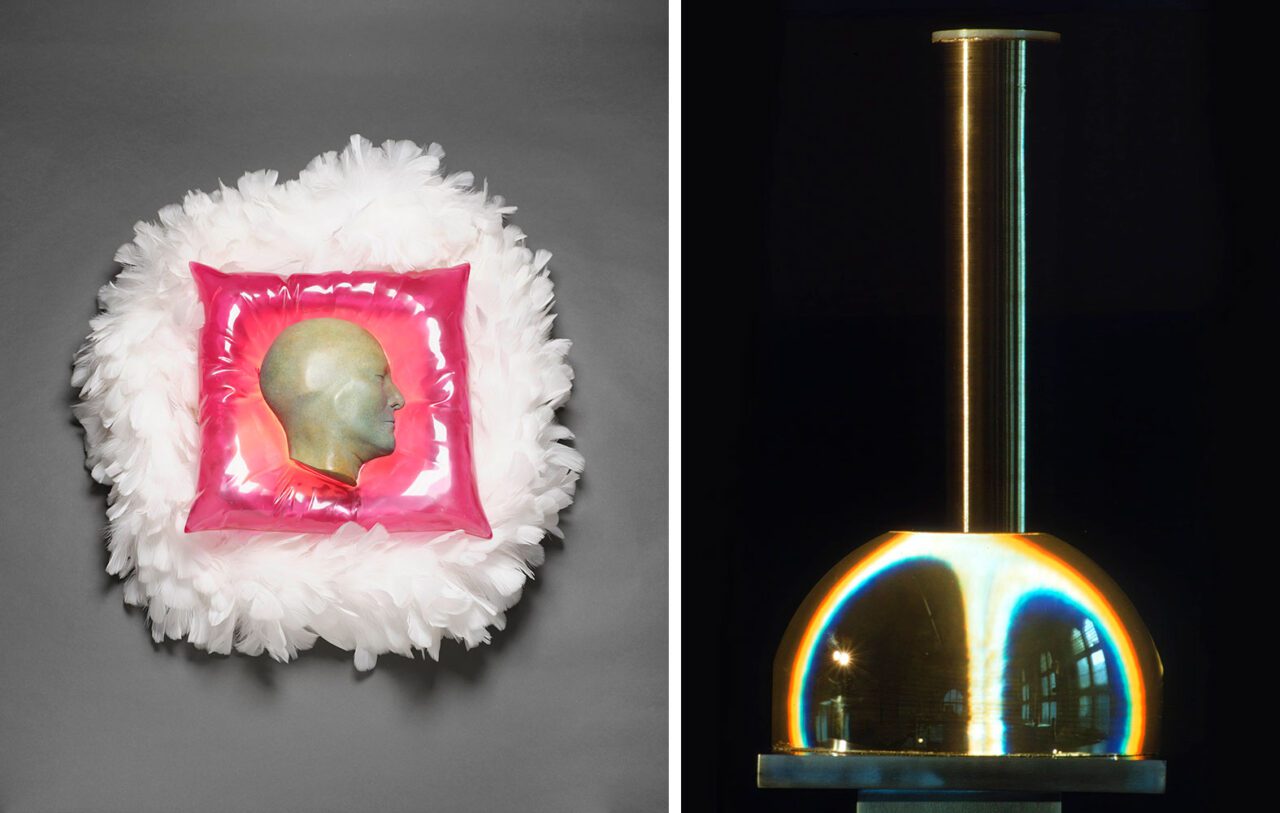

Liliane Lijn’s experimentation (1968) with light and movement culminated in the groundbreaking artwork “Liquid Reflections”, which was inspired by her interest in astronomy and physics. Liquid Reflections is comprised of a hollow, rotating Plexiglas disk containing water. The spinning causes the liquid to condense into droplets that act as natural lenses. Placed atop the disk’s surface are two Plexiglas spheres, the motion of which is determined by two opposing forces: the centrifugal force of the rotating disk and the centripetal force of its concave curvature. Illuminated by a fixed light source, the spheres are transformed into magnifying lenses that give rise to a dynamic and unpredictable interplay of light and shadow. They orbit across the transparent surface like celestial bodies and, in miniature, offer us a glimpse into the mysteries of the universe. In several series of drawings produced over the course of the seventies, Liliane Lijn drew lines of connection between broader conceptions of movement and dynamics with the unceasing flow of the unconscious and principles borrowed from the field of cartography. While her “Flow Lines”, minimalist pencil drawings produced between 1975 and 1977— employ an automatized script of the unconscious and use recurring graphic marks to present the process of mark-making itself as a ceaseless flow and a practice of directing energy, her “Lunar Traces” from 1978 tentatively begin to embrace the use of color. For these works, Lijn took inspiration from the earthen tones of the barren, moonlike landscape she had witnessed in Carboneras, a coastal village in Andalusia. With her “Windows (Starskins)” series, produced in 1979, Lijn’s practice departed the earthly realm. As she had done for Sky Scrolls precisely twenty years earlier, Lijn turned her gaze toward the heavens. These drawings purport in their very title to map the surface of stars, to depict their “skin”—while knowing full well that stars are primarily composed of hydrogen and helium, and that what we see in the night sky is in fact pure light. In order to create the effect of a glowing skin, Lijn rubbed countless layers of luminous pastel onto the paper surface, before blending and brightening them by working over them with lighter pastel tones. Shown for the first time at the Venice Biennale in 1986, “Conjunction of Opposites” marks a highpoint in Lijn’s artistic production during the eighties. This performative installation—to which a separate room in the center of the exhibition space is dedicated— presents two female figures engaged in a dialog: “Lady of the Wild Things” from 1983 and “Woman of War” from 1986. Both sculptures form part of a series of works that Lijn refers to as Cosmic Dramas, and in which sound, movement, and a range of lighting effects combine to create a theatrical Gesamtkunstwerk. Both sculptures, which Lijn brings together in Conjunction of Opposites, reference” mythological figures that are conceived as po:lar opposites: in Lijn’s conception, “Lady of the Wild Things” embodies an early Greek tutelary goddess of nature. Her incarnation of this ancient deity takes the form of a figure that is designed with great technical sophistication and is highly artificial in appearance, with the ability to translate acoustic signals into dynamic light patterns—an archetype of absorbing or receiving, dressed in strikingly technical garb. In contrast, “Woman of War” stands for active, externally directed energies such as aggression and rage. During the course of the performance piece, this bellicose figure sings in Lijn’s voice, uttering a warning to humanity—to which her counterpart responds with light signals. In addition to her engagement with female forms in her sculptural work from the late seventies onwards, Lijn also addressed this theme through the mediums of painting and drawing. In series of artworks like “She” (1984–86) and the “Inner Portraits: (1985–89), she endeavored to capture the various aspects of the feminine through visual means and to redefine these on her own terms. In the process of doing so, Lijn tended to follow her intuition: instead of pre-planning her compositions, she employed mark-making techniques that, similar to the automatic writing of Surrealism, sought to open a door to the unconscious. “Electric Bride” (1989) is the final figure in Lijn’s “Cosmic Dramas” series and depicts yet another female archetype: the bride. This expansive figure, which is presented here in a separate room, is confined in a steel cage, to which she is attached by red-hot wires. In comparison to Lijn’s other robotic sculptures, the form of this figure feels more organic: her throbbing head is made of blown glass, and her body is composed of myriad layers of mineral micanite. In the voice of Japanese singer Shirai Takako, the bride whispers a poem in which Lijn references the legend of the Sumerian goddess Inanna and her descent into the underworld. With “Sweet Solar Dreams”(2002-)22, Lijn returned, as she entered the new millennium, to one of the key themes occupying Surrealism: dreams and the unconscious. Each of the three sculptures in this series- is identically constructed: a head in profile view, nestled in a synthetic pillow, each of which is itself surrounded by a range of different materials. The figures’ eyes are shut, and the heads appear to be sleeping. Each of the sculptures represents a specific stage of the sleep process: dozing off in the evening, the deep sleep of the dead of night, and, in the artwork shown here, the light slumber of the morning hours. On the audio track, we hear Lijn’s own voice recounting the events of a dream—her battle with a gigantic bird, which is alluded to by the white feathers that encircle the head on its pillow like a corona. The realistic profile figures featured in “Sweet Solar Dreams” are all casts of the artist’s own head. In the late nineties, Lijn abandoned abstract archetypes in favor of using her own body, fragments of which have found their way into her sculptures over the years.

Photo: Liliane Lijn, Liquid Reflections/ Series 2 (32″), 1968, Acrylic drum containing water, turntable and projector lamp, acrylic balls, 81,3 cm in diameter, Courtesy Liliane Lijn and Sylvia Kouvali, London / Piraeus, Photo: Stephen Weiss, © Bildrecht, Wien 2024

Info: Curator: Manuela Ammer, mumok (museum moderner kunst stiftung ludwig wien), Museumsplatz 1, Vienna, Austria, Duration: 15/11/2024-5/4/2025, Days & Hours: Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00, www.mumok.at/

Right: Liliane Lijn, Denslens, 1974–75, Rotating column of Perspex wound with nickel wire, pronounced pattern, set on motorized turntable, 51 x 5 cm diameter, 10 cm diameter at base, Courtesy Liliane Lijn and Sylvia Kouvali, London / Piraeus, Photo: Stephen Weiss, © Bildrecht, Wien 2024

Right: Liliane Lijn, Inner Space Outer Space 1, 1969, Collage, 56 x 55 cm, Courtesy Stephen Weiss, London, Photo: Stephen Weiss, © Bildrecht, Wien 2024