TRIBUTE: Electric Dreams-Art and Technology Before the Internet, Part II

From the birth of op art to the dawn of the internet age, artists found new ways to engage the senses and play with our perception. The exhibition “Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet” celebrates the early innovators of optical, kinetic, programmed and digital art, who pioneered a new era of immersive sensory installations and automatically-generated works (Part I).

From the birth of op art to the dawn of the internet age, artists found new ways to engage the senses and play with our perception. The exhibition “Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet” celebrates the early innovators of optical, kinetic, programmed and digital art, who pioneered a new era of immersive sensory installations and automatically-generated works (Part I).

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Tate Archive

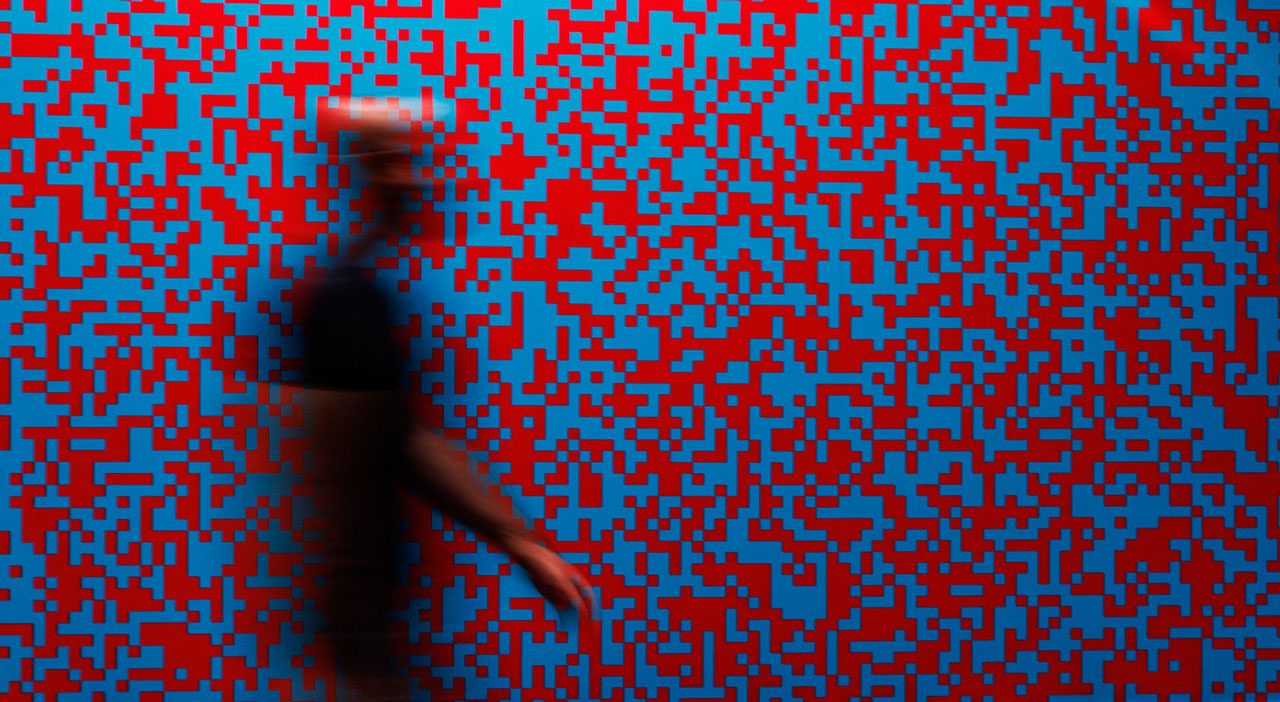

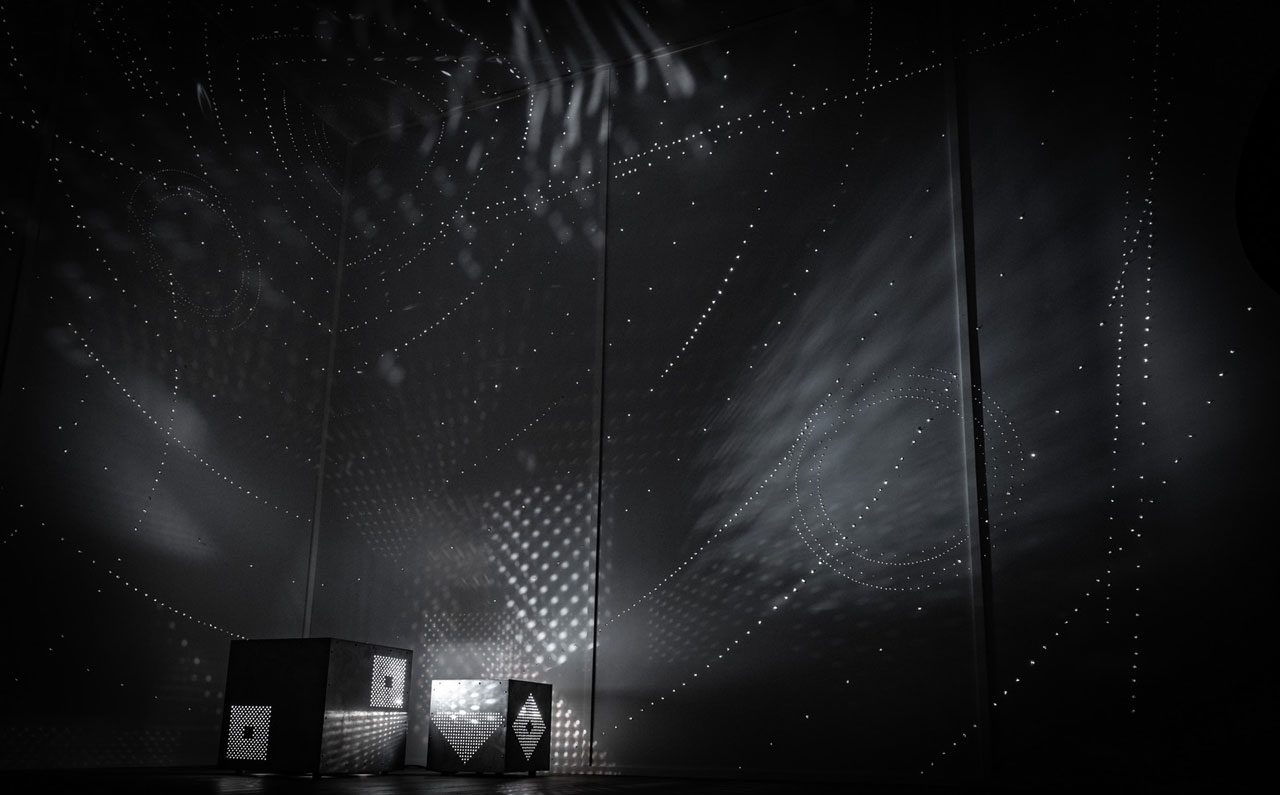

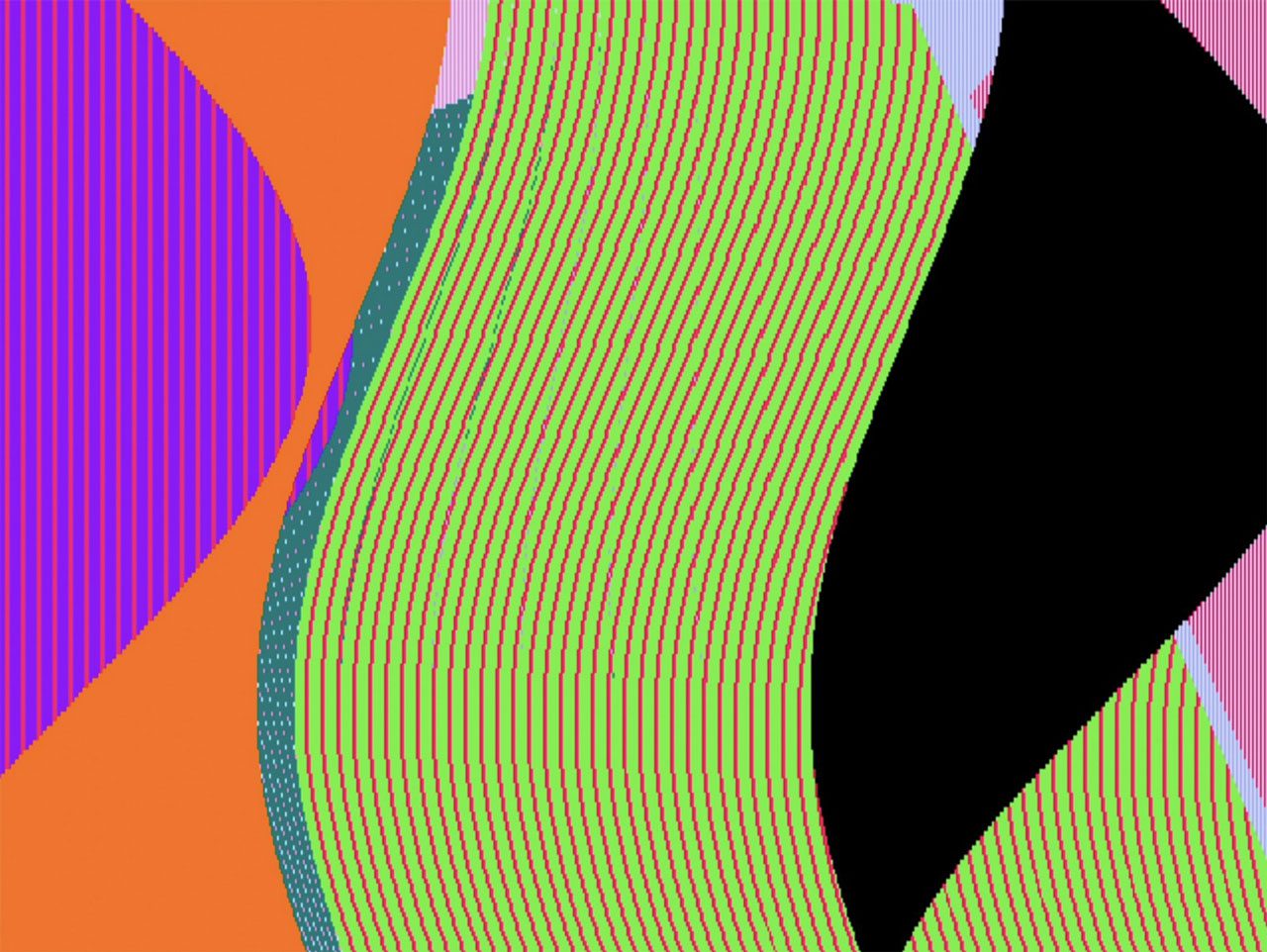

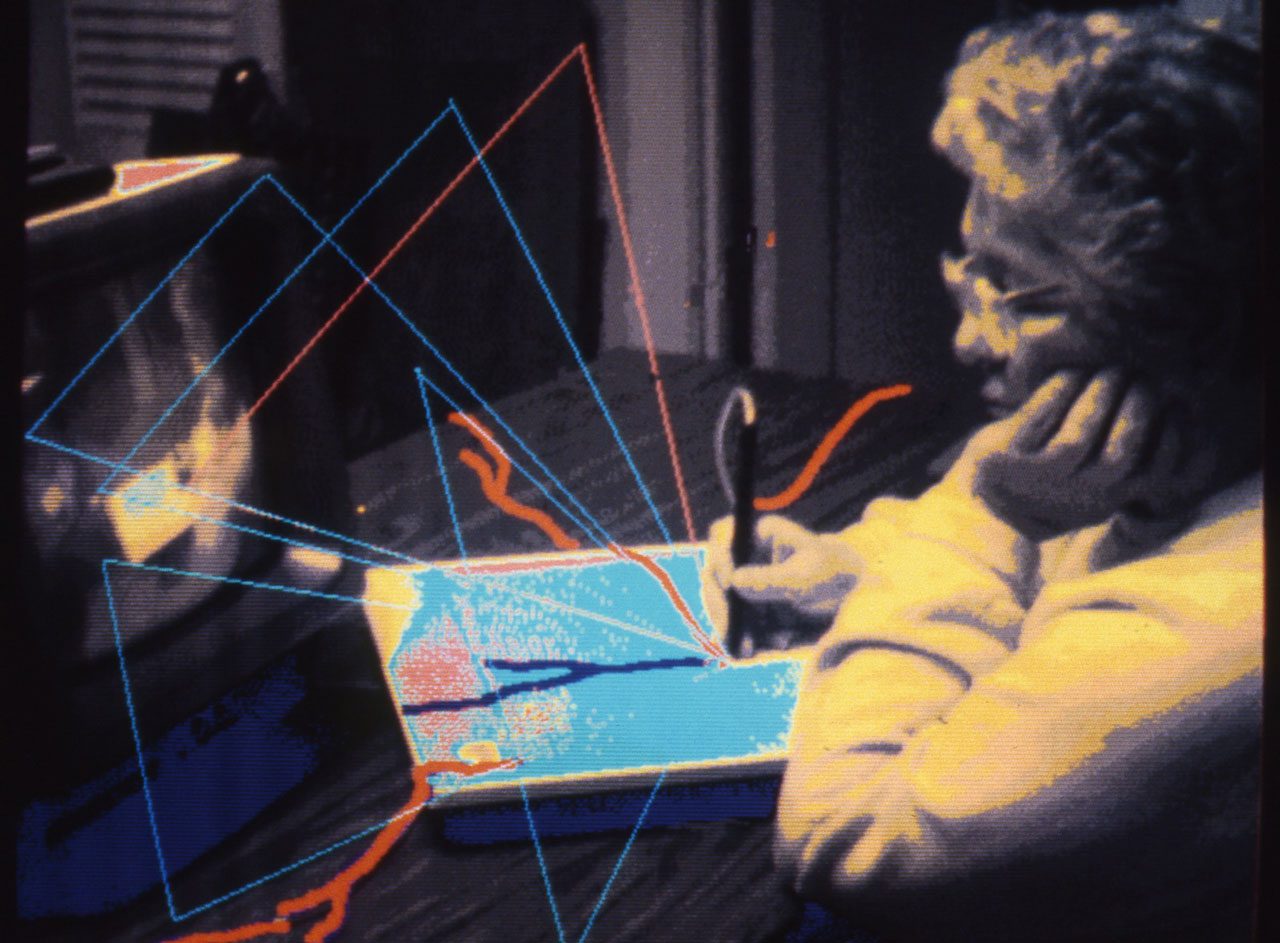

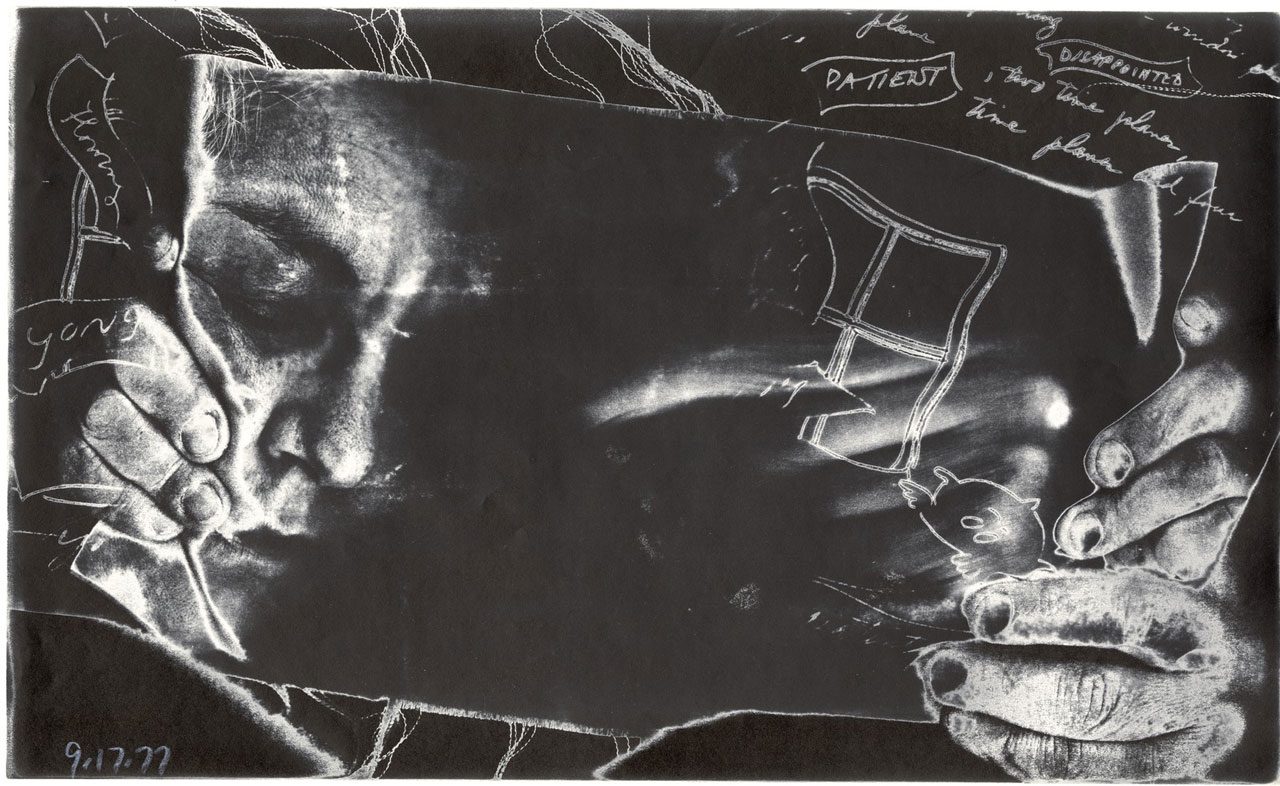

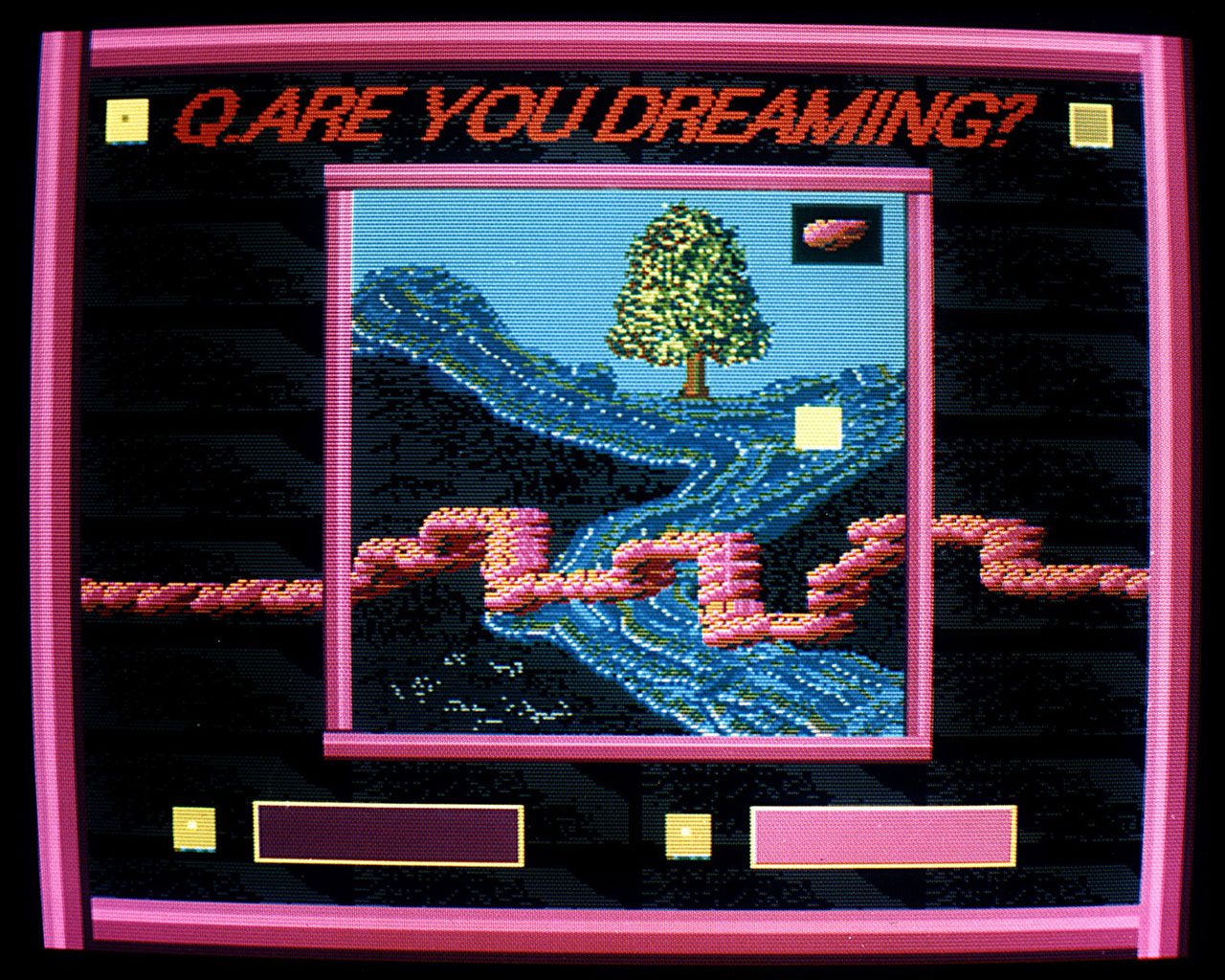

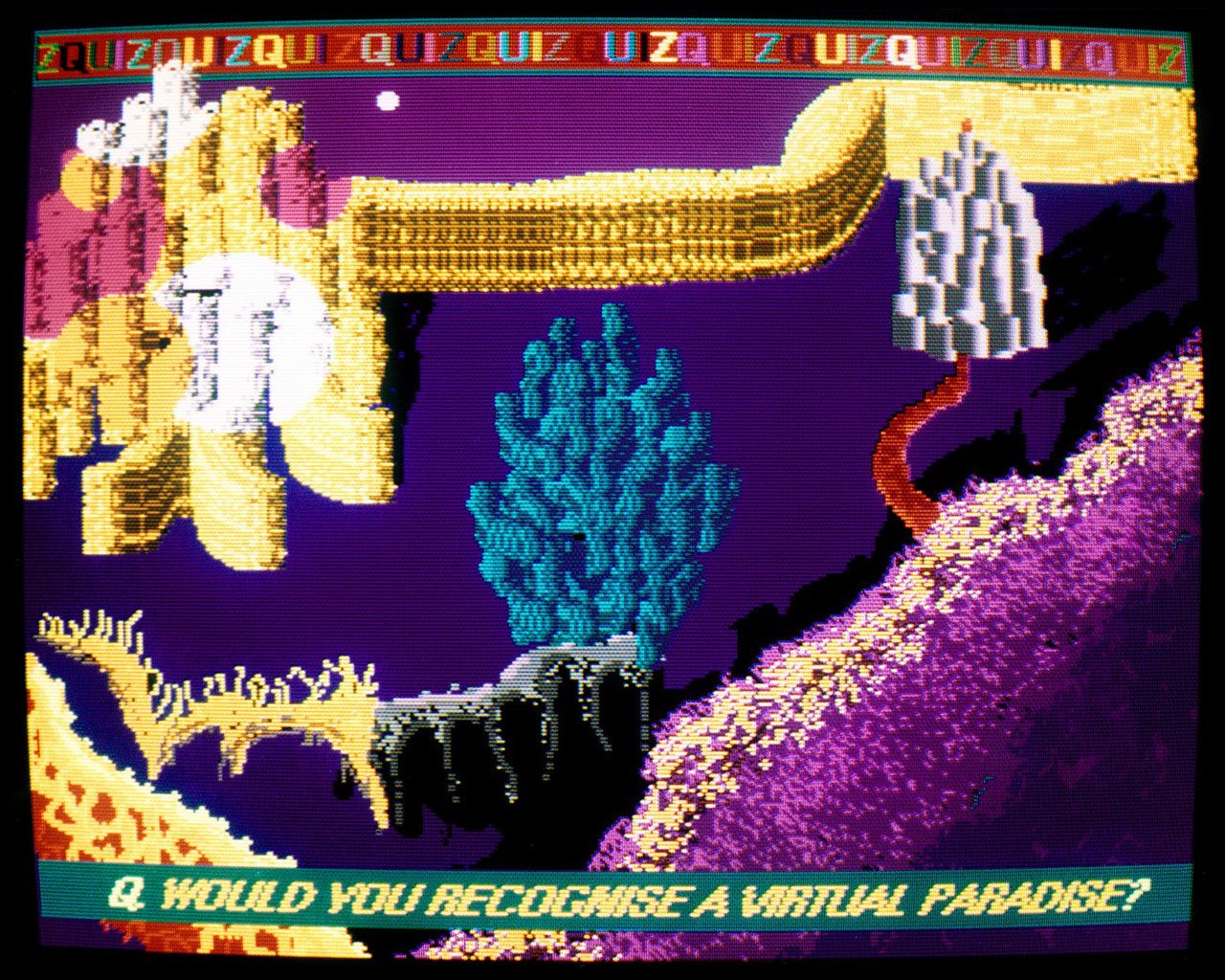

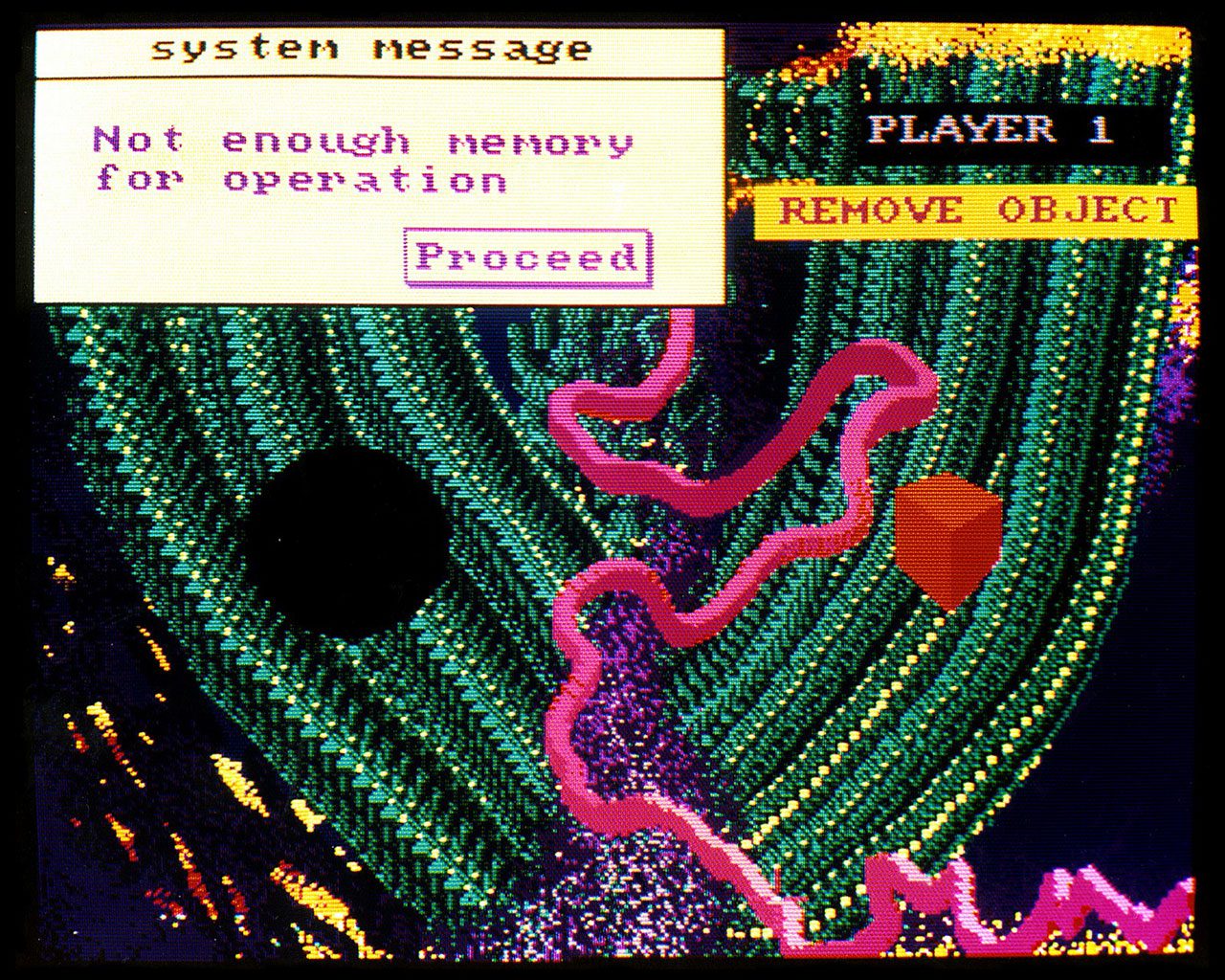

The exhibition “Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet”, brings together groundbreaking works by 70 international artists who engaged with science, technology and material innovation. These groundbreaking figures from across Asia, Europe and the Americas responded to the growing presence of technology in our lives by finding new ways to work with machines – often reclaiming them from the military and corporate interests that drove their evolution. Featuring over 150 works, many of which are shown in the UK for the first time, this ambitious exhibition is a rare opportunity to experience incredible vintage tech art in action – from mesmerising psychedelic installations to early experiments made with home computers and video synthesisers. “Electric Dreams” explores how artists used cutting-edge tools to expand cultural horizons and imagine the future we are now living in. Immersive installations are featured throughout the exhibition, bringing to life radical experiments with light from across five decades. Photographs documenting the iconic “Electric Dress” 1957 by Japanese artist Atsuko Tanaka of the Gutai group are shown alongside her stunning circuit-like drawings. German artist Otto Piene’s “Light Room (Jena)” surrounds viewers in a continuous light ‘ballet’, while Venezuelan artist Carlos Cruz Diez’s captivating “Chromointerferent Environment” (1974-2009) uses moving projections to create a mind-bending lattice of colored lines that challenges our perceptions of color and space. British-Canadian Brion Gysin’s homemade mechanical device, “Dreamachine no.9” (1960-76) creates kaleidoscopic patterns that induce a dream-like state in the viewer, and Japanese artist Tatsuo Miyajima’s eight-metre-long wall installation of flashing LED lights, “Lattice B” (1990), meditates on how time is measured and understood. “Dreamachine no.9” was conceived by Brion Gysin, along with his friend Ian Sommerville, iy is the first object in history designed to be viewed with closed eyes. The Dreamachine simply consists of a cylinder with holes cut into the sides which is placed on a turntable. A lightbulb is suspended in the center of the spinning cylinder. The light passes through the holes as it rotates at a constant frequency, situated between 8 and 13 pulses per second. This frequency range corresponds to the ‘alpha waves’, electrical oscillations naturally present in human brain when the eyes are closed and no stimuli are processed, e.g., when there’s a relaxed and effortless alertness, and while meditating. The work is viewed with the eyes closed: the flickering light stimulates the optic nerve and alters the brain’s electrical oscillations, producing vivid visions of very bright moving and morphing colors in geometrical patterns which appear “projected” behind the eyelids, covering the field of vision completely. A prolonged session in front of a Dreamachine (time may vary among subjects) can push the experience further, altering the perception of time and space and provoking a dream-like state. The user should sit comfortably in front of the Dreamachine, with the eyes approximately at center (half height) of the cylinder and quite close (5 cm), but is good to try and find what is best. Music can be played, even if it has been noted that music with words tends to “distract” and interfere. These works are interspersed with a series of group rooms reuniting artists from key historic exhibitions, highlighting their shared interests in abstraction, kineticism, perception, information theory and cybernetics. They include early shows staged by ZERO – a German-based group founded in the 1950s by Heinz Mack and Otto Piene, as well as the influential series of “New Tendencies” exhibitions of the 1960s, which firmly established Zagreb as an epicentre of kinetic and digital art. Aleksandar Srnec and Julio Le Parc’s use of geometric structures and light to create optical effects are shown alongside works by members of Italy’s Arte Programmata groups including Marina Apollonio and Grazia Varisco. London’s own groundbreaking ‘Cybernetic Serendipity’ exhibition held at the ICA in 1968 is explored alongside US artist Harold Cohen’s 1979 painting based on drawings generated by his software AARON, an early precursor of today’s art-making AIs. Works adopting a DIY ethos are also brought together, showing how artists developed their own hi-tech tools and techniques, including the video synthesizer used by Nam June Paik from Korea, and the experiments with photocopiers and computer graphics by Sonia Landy Sheridan from the USA. Many of the artists in the exhibition were among the very first to adopt new digital technologies in their radical experiments. US artist Rebecca Allen developed cutting-edge motion-capture and 3D modelling techniques in the 1980s, while Brazilian artist Eduardo Kac produced colorful text poems using Minitel machines, a form of networked computing that anticipated the widespread adoption of the internet. Art made on early home computers includes Palestinian artist Samia Halaby’s trailblazing kinetic paintings created after teaching herself how to code on an Amiga 1000, and British artist Suzanne Treister’s series of prescient “Fictional Videogame Stills” from the early 1990s. The exhibition culminates with some of the earliest artistic experiments in virtual reality, which paved the way for today’s immersive digital technologies. “Liquid Views” (1992), an interactive installation by Monika Fleischmann and Wolfgang Strauss, invite visitors to play with their image ‘reflected’ on a touchscreen that acts as a pool of digital water, while footage of “Inherent Rights, Vision Rights” (1992), a virtual environment simulating mystical visions created by Canadian First Nations artist Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun is shown on a vintage CRT monitor.

Works by: Rebecca Allen, Marina Apollonio, Manuel Barbadillo, Alberto Biasi, Vladimir Bonačić, Davide Boriani, Martha Boto, Pol Bury, Harold Cohen, Analivia Cordeiro, Waldemar Cordeiro, Carlos Cruz-Diez, Charles Csuri, Computer Technique Group, Dadamaino, Atul Desai, Lucia Di Luciano, Ivan Dryer and Elsa Garmire, E.A.T., Monika Fleischmann and Wolfgang Strauss, Herbert W. Franke, Brion Gysin, Samia Halaby, Desmond Paul Henry, Hervé Huitric and Monique Nahas, Edward Ihnatowicz, Eduardo Kac, Hiroshi Kawano, Ben Laposky, Julio Le Parc, Ruth Leavitt, Liliane Lijn, Heinz Mack, Robert Mallary, Mary Martin, Almir Mavignier, Gustav Metzger, David Medalla, Tatsuo Miyajima, Manfred Mohr, Vera Molnar, François Morellet, Tomislav Mikulić, Fujiko Nakaya, Frieder Nake, Georg Nees, Akbar Padamsee, Nam June Paik and Jud Yalkut, Ivan Picelj, Otto Piene, Günther Uecker, Paolo Scheggi, Lillian F. Schwartz, Sonia Landy Sheridan, Aleksandar Srnec, Jesús Rafael Soto, Vera Spencer, Takis, Atsuko Tanaka, Jean Tinguely, Franciszka Themerson, Suzanne Treister, Wen-Ying Tsai, Grazia Varisco, Steina and Woody Vasulka, Mohsen Vaziri Moghaddam, Miguel Ángel Vidal, Nanda Vigo, Stephen Willats, Katsuhiro Yamaguchi, Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun, Edward Zajec.

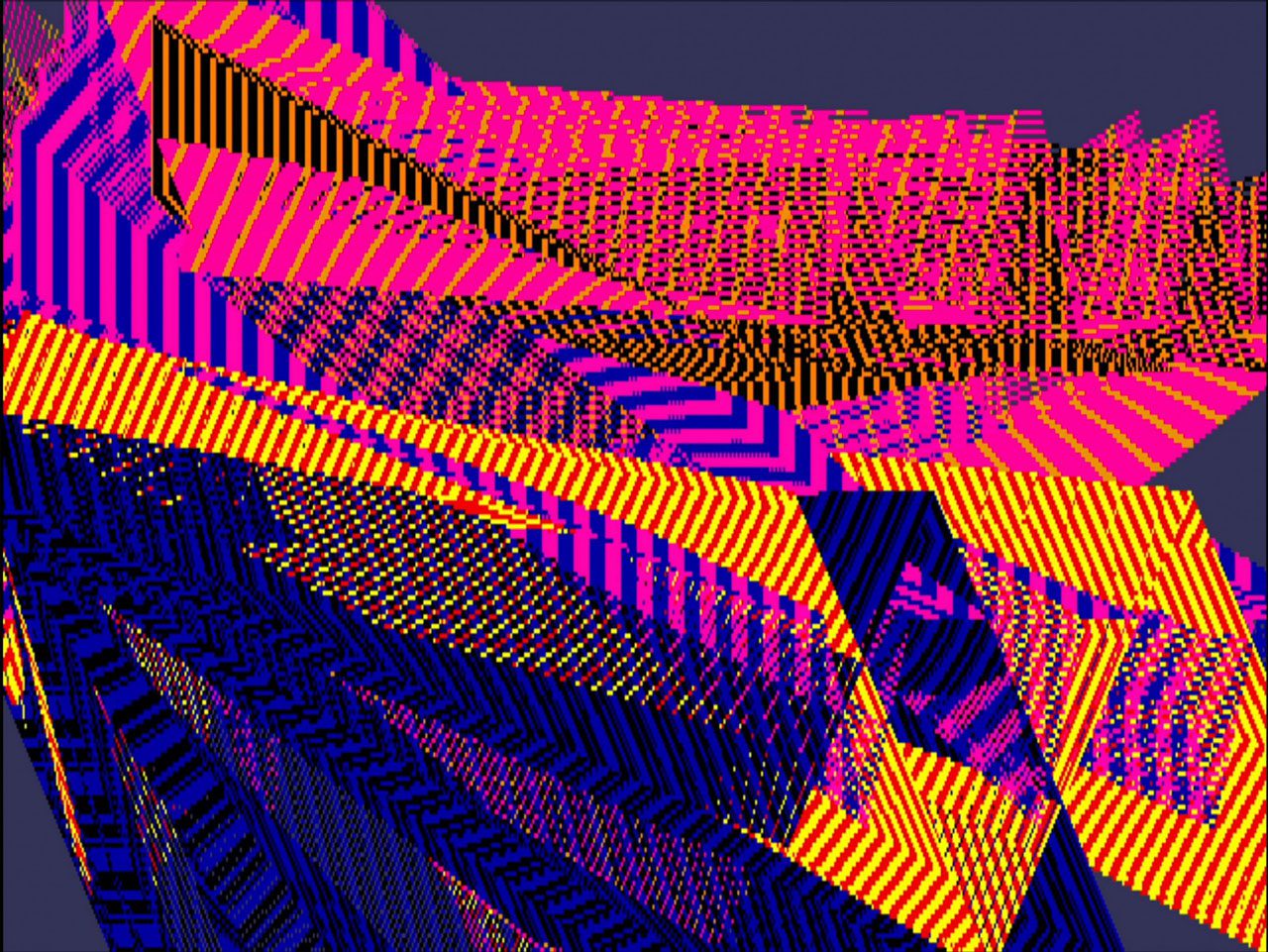

Photo: Samia Halaby, Fold 2 1988, still from kinetic painting coded on an Amiga computer. Tate © Courtesy the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Beirut / Hamburg

Info: Curators: Val Ravaglia, Odessa Warren andKira Wainstein, Tate Modern, Bankside, London, United Kingdom, Duration: 28/11/2024-1/6/2025, Days & Hours: Daily 10:00-18:00, www.tate.org.uk/