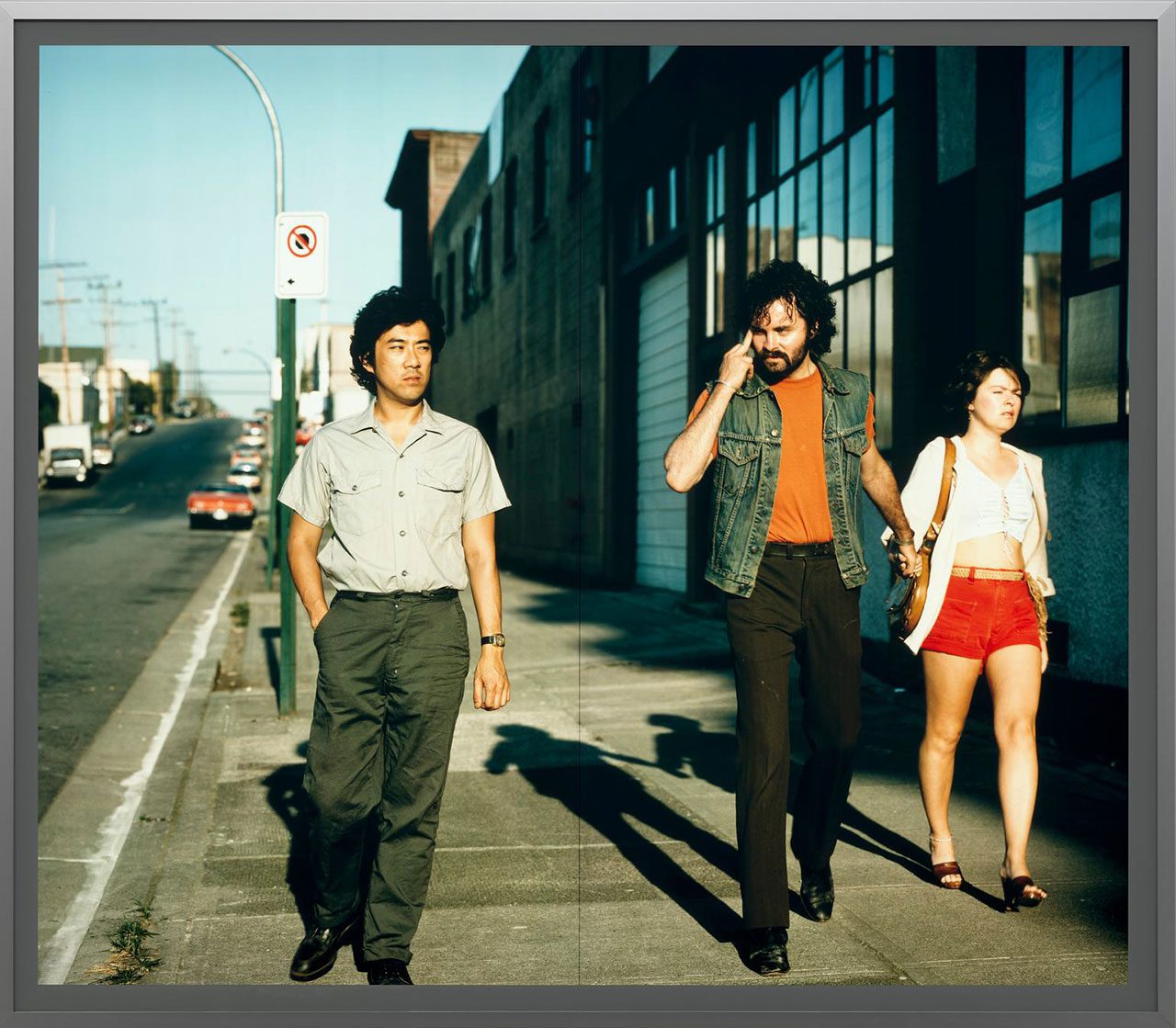

PHOTO: Jeff Wall-Life in Pictures

The photography of Jeff Wall is consciously and profoundly saturated in the social: in the Vancouver art community from which he first emerged, fully formed, in the late 1970s; in the racial and gender politics of our times, which he analyses with marvelous clarity in his huge photographic light boxes that declare an equal status with painting through their scale and their carefully plotted depth.

The photography of Jeff Wall is consciously and profoundly saturated in the social: in the Vancouver art community from which he first emerged, fully formed, in the late 1970s; in the racial and gender politics of our times, which he analyses with marvelous clarity in his huge photographic light boxes that declare an equal status with painting through their scale and their carefully plotted depth.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: White Cube Archive

In the art history pantheon that informs Jeff Wall’s staged compositions, from Hokusai to Velásquez and Manet; and in his influence on at least two generations of photographers, most notably the Düsseldorf school (Andreas Gursky once cited Wall as “a great model for me”). White Cube present “Life in Pictures”, a comprehensive solo exhibition of works by Jeff Wall, marking 30 years of White Cube’s collaboration with the artist, this presentation brings together over 30 key works from Wall’s oeuvre including his series of iconic light-boxes as well as new pictures. Jeff Wall grew up in Vancouver. His interest in art encouraged by his parents, and by the age of 14, he was painting in the shed in the back yard. He was inspired early on by developments in painting, such as the work of American abstract artist Jackson Pollock, whose paintings he saw at the Seattle World’s Fair in 1962. Wall received his BA in art history from the University of British Columbia in 1968 and completed his MA at UBC in 1970 with a thesis on German Dada artist John Heartfield entitled “Berlin Dada and the Notion of Context”. He went on to do postgraduate work in a doctoral program in London, England, at the Courtauld Institute (1970–73), where he undertook a thesis, which he never completed, on pioneering French artist Marcel Duchamp. Upon his return to Canada, he became an assistant professor at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design (1974–75) and then an associate professor at Simon Fraser University (1976–87). He was a professor at UBC until his retirement in 1999. While studying art history at UBC, he gave up painting and began to experiment with conceptual art in the form of photographs with text as well as film. In 1970, his work appeared in an exhibition of conceptual art titled “Information” at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. At that point, Wall felt he had hit an artistic block and gave up making art altogether. Jeff Wall made no art again until 1977, when he produced his first back-lit photo-transparency. The pictures are staged and often refer to the history of art and philosophical problems of representation. Wall’s objective has been to recover modernist imperatives to rescue society from what he came to consider the dead end of conceptualism. Wall’s central place in international contemporary art was established when he appeared in the significant European exhibition “Westkunst: Zeitgenössische Kunst seit 1939” (1981) at the Rheinhallen Messegelände in Cologne, Germany. Wall’s work is underpinned by his considerable body of theoretical writing that advances an argument for the necessity of pictorial art. Much of his work pictures social tension, cities with changing demographics, intersections, suburbs and dead zones. Other work is much more enigmatic, fantastic and seemingly personal. Wall’s photographs are complicated productions involving casts, sets and crews as well as digital and post-shoot manipulation. They have been characterized as one-frame cinematic productions rather than photographs in the ordinary sense. They address the history of painting more than the history of photography. Among Wall’s earliest iconic photographs, and one that encapsulates many of the themes that run through his career, is “Picture for Women” (1979). Inspired by Édouard Manet’s iconic “A Bar at the Folies-Bergeres” (1881) and Shot directly into a mirror, “Picture for Women” has the young Wall, dressed in black slacks and a T-shirt, holding the camera’s plunger and gazing into the picture pensively; in the foreground is a woman in street clothes with her hands folded on a wooden work table, frowning slightly, eyes averted, her expression one of impatience and perhaps also of ambivalence. “The Storyteller” (1986), on the other hand, is a larger and more elaborately orchestrated image. Set on the grassy slope below a concrete highway overpass, the sky slate grey, the photograph has three Indigenous men in the foreground sitting around a small campfire, one, squatting alertly, his mouth open and his hand gesticulating forcefully as though emphasizing a line — he is obviously the storyteller of the title. Behind them, in front of a towering, dense stand of pines, a couple, who look like they are listening to the story from a distance, lounges on the grass; below the cement ramparts of the overpass sits a man, hands folded, face scowling, who looks like he is alienated from the rest. As is often the case with Wall, “The Storyteller” is a complex composition with multiple levels of irony. Here are Indigenous people engaged in a traditional practice, homeless on their own land, which has been occupied and fragmented. In addition, the Indigenous people themselves look disoriented and fragmented: while two are rapt listening to the story, the others are adrift on the periphery. Wall’s large-scale, dramatic lightbox photographs are well-known for their often explicit allusions to 19th-century French paintings, especially the work of Édouard Manet. At the Courtauld Institute, Wall was a student of T.J. Clark, one of the preeminent scholars of 19th-century French paintings and modernism. Beginning in the 1990s, Wall began making works that allude to a different painting tradition — that of still lives and landscapes. “An Octopus” (1990), for instance, has an octopus at mid-distance, sensuous but also mysterious, on a work table casting shadows on the wall; the wall, with its slatted boards and weathered green stucco, looks like the wall of an old workshop. “Dead Troops Talk” (1991–92), a large image depicting a hallucinatory moment from the Soviet war in Afghanistan, is a central example, and was one of the first works to employ digital-imaging technology, which has since transformed the landscape of photography. Wall was a pioneer in exploring this dimension and remains at the forefront of its development. A second key direction in Wall’s work is what he calls the “near documentary.” These are pictures that resemble documentary photographs in style and manner but are made in collaboration with the people who appear in them. Wall works mostly with nonprofessional models in a way that recalls the neorealism of the Italian cinema of the 1950s and 1960s, creating images of everyday moments charged with complex meanings. By depicting incidents that he witnesses but does not attempt to photograph in the moment, he opens up formal and dramatic possibilities for pictures that, he has said, “contemplate the effects and meanings of documentary photographs.”

Photo: Jeff Wall, The Flooded Grave, 1998 – 2000, Transparency in lightbox, 228.5 x 282 cm | 89 15/16 x 111 in., 248 x 301 x 26 cm | 97 5/8 x 118 1/2 x 10 1/4 in. (framed), © Jeff Wall, Courtesy the artist and White Cube Gallery

Info: White Cube Gallery, 144-152 Bermondsey Street, London, United Kingdom, Duration: 22/11/2024-11/1/2025, Days & Hours: Tue-Wed & Fri-Sat 10:00-18:00, Thu 18:30-20:00, Sun 12:00-18:00, www.whitecube.com/